M.C. Escher. Dulwich Picture Gallery

M.C. Escher was the kind of artist who was wheeled out to us students in the final years of high school. His graphic work appealed to our teenage fan art illustrative style, pencil and biro portraits of the Manic Street Preachers, blur and Suede that hung in our lockers, the cuboid shapes and constructions scratched in boredom throughout our homework diaries. But Escher also ticked a lot of art class boxes; enabling our teacher to demonstrate how to use perspective, shading, mark making, pattern and reflection. An extra bonus was that the artist’s work appealed to other departments in the school, the proper departments such as maths and science – a reasonably sized poster of one of Escher’s tessellating bird compositions adorning our maths classroom wall for several years. By the time art school rolled around Escher was a bit of a dirty word, you would never dream of citing him as reference – not contemporary enough, not cool enough. The kind of artist that belonged to dated sci-fi or fantasy books. Certainly not in a gallery. I don’t think, to date, I’ve ever seen in his work in a show.

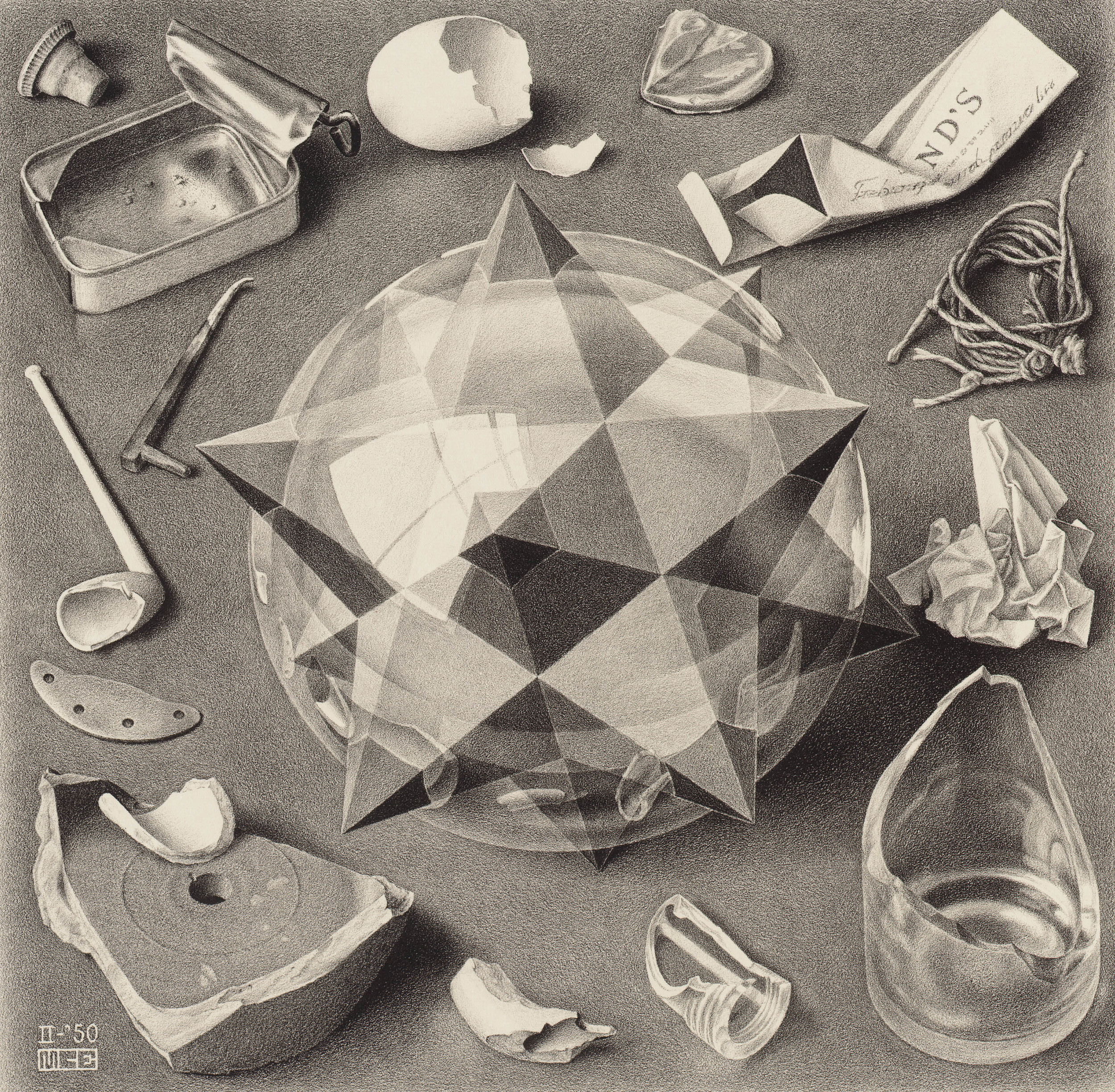

Contrast. M.C. Escher (Lithograph. 1950)

Now, in advancing years and a world away from the disapproving looks and conceptual triangles of art school lecturers, Escher’s work seems ripe for rediscovery and a new exhibition ‘The Amazing World of M.C. Escher‘ just opened at Dulwich Picture Gallery, allows for this re-acquaintance. The exhibition (originally organised by the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art) is, surprisingly, the first major solo exhibition of the Dutch artist's work in the UK and brings together around 100 drawings, prints, lithographs, mezzotints alongside a selection of archival material.

Dewdrop. M.C. Escher (1948)

Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898-1972) started out studying architecture in Haarlem, Holland, before moving into the Department of Graphic Arts. He would go on to produce around 500 prints and woodcuts and over 2000 drawings and sketches over his lifetime. Travelling throughout Europe after graduation he became fascinated by Italian and, later, Spanish architecture and landscape, pattern and decorative style and these influences can be seen throughout his work. The Moorish tiling of his tessellations, the classical cake-like Italianate architecture of his towers, castles, streets and dwellings. Demand for Escher’s work reached a peak at right towards the end of his life, in the 1960’s. Elements of a sci-fi Futurism combined with a romantic dilapidated past appealed to the aesthetic of the time; Rover, the balloon-like thing, float-stalking the Escher-like endless up and down streets of Portmerion in The Prisoner; or the world within world’s shown in The Twilight Zone. Looking at several spherical and orby-based reflection works in the exhibition such as Three Spheres II (Lithograph. 1946), Eye (Mezzotint. 1946) or even Dewdrop (Mezzotint. 1946) I was reminded of last year’s Black Mirror Christmas special from Charlie Brooker which closed on the scene of the endless universe within universe, reality within reality, revealed inside the globe of a snow dome; over and over, infinite loop.

Belvedere. M.C. Escher (1958)

Escher, in my memory, had always been about architectural structure and landscape, ladders and stairs. When the human figure featured they always seemed as specific details of the body, an eye, a head or portion of face in close-up or distorted. It was surprising, therefore, to notice the individual people that inhabit some of his work. The soft-fuzz detail in his familiar surreal criss-cross staircases (such as in Relativity, 1953) revealed to me, on closer inspection a whole army of faceless worker citizens going about their business; delivering wine and pails of water to unknown recipients, tucking into plates of bread and chicken or simply gazing out the window. One couple strolls in the outside garden, a plane shifted in Escher perspective harshly to the left as if they are falling down hill, the man’s arm around the waist of his partner. This is a romance in a world with no up or down.

Relativity. M.C. Escher (1953)

Other details are revealed elsewhere. In the bird tessellation from my high school maths class (Day and Night, 1938), I notice for the first time the little fortressed villages at the bottom of the print. Two tiny Dutch mini towns with small houses surrounding a church or cathedral, a windmill, a factory – self-sufficient. Roads lead off into the flat landscape around are shown in mirror, one village in day, and one in night. They could be the same town shown in different states or different towns entirely – on other sides of the world, or a parallel planet. Perhaps with mirrored people, following different life trajectories. Another Earth.

MC Escher

‘The Amazing World of M.C Escher’ runs until January 2016 at Dulwich Picture Gallery

Escher Lates. 7 November/14 January. 5.30-8.30 pm

Escher Meets Inception. 30 October. 6.30-11p