Meet Shirin Neshat

Shirin is a renowned visual artist who works across photography, video installation, and film. In this conversation, she generously shares how each stage of her life has led her to today: from her upbringing in Iran to her youth in California and her life now in New York. Her dedication to ritual and to her artistic practice has remained consistent through the tumult and triumph of all her days.

♫ Listen to shirin's playlist | ⌨ shirin's last google search

on her morning routine

I'm an early riser; I usually get up around 6:30 am and wake up to my dog, who sleeps above my head. With my eyes closed and before I even wash my face, I feed him and put the coffee on because I am absolutely 100% addicted. Usually, I write in my diary about the day before and depending on how I feel, I try to give myself a mantra for the day. During this morning ritual, I'm completely alone with the dog and try to prepare myself mentally for the day or just make peace with whatever is going on that I am stressed about. By 7:30 am, I go out for a 45-minute walk or jog with my dog. If I need time to just process things, I don't put headphones on. Otherwise, I listen to podcasts like the New York Times' The Daily and NPR's Fresh Air to catch up with what's going on in the world. And I'll often pick up an empanada from a Colombian bakery on Wyckoff to eat in the morning; I like to eat basically the same thing every day, morning and night, and I don't usually eat lunch. I’m very much a creature of habit. Then, once I'm back, my day starts.

on her upbringing and family life

When I was young, I had this picture of what happy families looked like, this quintessential idea of a good upbringing. My family lived in a big house with a big garden. There were five of us, and we had really loving parents. But as we got older, our parents put us in boarding school and we all separated and haven’t been as close since.

I really haven't been in a nuclear family situation since then. I did get married to my ex-husband Kyong, who I met about 2 years after I moved to New York. It was temporarily successful, but it didn't last very long: we were in love, and he was doing amazing work, so I spent 10 years following him. We had a child. But I think that I always sought out this concept of a nuclear family because it gives you a sense of security, especially when you're away from where you were born. I think part of my attraction to him was that he was also not really American: he was Korean and similarly dealt with family displacement, so I felt like we were a good team. But it didn't turn out to be that way.

““I think for people who are nomadic or travel a lot, rituals are especially important because you can take them with you to another place. For example, when I was in New Mexico for five months shooting my upcoming movie, I still walked my dog, called my mother, made that cup of coffee, and wrote in my journal. And that’s what I did every day. Having those attachments is very helpful for me, and I try to never break them.””

on the culture shock upon arriving in the U.S.

I came to this country when I was 17, and I hated it. I grew up like many Iranian people in my generation, fantasizing about America, through Hollywood. It was my father's dream that his children become Americanized. But when I arrived in Los Angeles, I felt a lot of depression—I really, really disliked the experience of life in America. We were always in the car and on the highways and in these ugly apartments, and I just terribly missed my home and the warmth of the family and friends I really wanted to go back to. I found myself completely alone at UC Berkeley—where I somehow got accepted. But it was '79 and during the Iranian Revolution. So that just sort of overshadowed my education at the time and where my concentration was because I really lost contact with my family. My income from my father stopped. And then, there was a diplomatic breakdown between Iran and the U.S. Then Iran started a war with Iraq; it was just like a nightmare. I felt very destabilized, very displaced. And there was major antagonism against Iranian students on the campus.

At this point, I had this very romantic idea of being an artist but was not a very good one. I was very immature and too young. So while my friends were all blossoming, I was doing very poorly. But I felt safe because I had friends who were the community that I needed to manage living through school. Unfortunately, I destroyed all evidence of the work I created through undergraduate and graduate school.

on identity and community

I've learned that I have different identities in my work and personhood: as a filmmaker, as a photographer, and having directed Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida. And I think it's really challenging. Sometimes among Iranian friends, I still feel a little bit like an outsider. My Farsi is not as perfect as some of theirs, or I don't know some of the nuances of Iranian culture because I left when I was young. And when I'm among Americans or Europeans, I also feel like a stranger to them.

After I met my partner Shoja, I gathered many Iranian people around me, and we became a community and a family. And I think, through working with Iranian people who are also artists and cinematographers, singers, production designers, writers, filmmakers, and many different people, we've all built this extended family where we depend on our circle of people and really help each other a lot.

““Whatever Iranian that stayed in me is very deep that came from my childhood. It never left me. It’s amazing. I never realized how much your childhood and upbringing sort of stamps you, your identity, like it really marks you. Certain things just remain with you forever. It’s really powerful.””

on moving to new york and becoming an artist

After graduating, I moved to NYC and became aware that I didn't have what it would take to become an artist. I realized that art is not something intuitive or that you were born gifted. You have to earn it, and I had not yet earned the knowledge of what material would help me come up with ideas. The next 10 years became my true education: I met a lot of artists and architects through the non-profit gallery my ex-husband, Kyong founded, Storefront for Art and Architecture. Eventually, when I did become an artist, my work was very research-based. It was not this intuitive thing where I would just, like, draw something. Instead, I spent a lot of time learning about material that interested me, and eventually, it sort of crystallized in the visual images I create.

on recognizing herself as an artist and achieving acclaim

I’ve never felt like a successful artist. But my work speaks for me, and I can come back to it and just start dreaming. Winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 1999 was totally unexpected, honestly. At that time, I had just done Turbulent and Rapture. They were two very strong works, and suddenly, everybody liked and talked about my work internationally. I was sort of caught unprepared. It felt really gratifying. Then, in 2009 in Venice, when I won for A Woman Without Men, it was a similar experience. I felt like a total beginner. And I struggled so much with that film. I don't think I've ever been happier—other than when my son was born—than when I got that award, because it really was so unexpected. That project was so painful.

her advice for aspiring visual artists and filmmakers

Don't make art for the art world, and don't make films just to get into festivals. Being an artist is such a commitment. It is so painful most of the time, so there has to be a really good reason why you're doing it. I always say to people that it's not a hobby; it's a full-time job. It's like art and life become one thing, which means you have to give it everything. My art has been my life, and my life has been my art. My story, as a human being within my circle of friends, always relates to the artwork. So if you think that you're going to travel around for fun and then come back to a studio where you deal with your pain, that's mistaken. It has to be immersive.

“I think my work was initially successful because it was not rooted in anything Western; it was so off the map. When I look at my work, there’s a lot of melancholy in it. I think that what I love about the Persian history of mysticism is how deeply melancholic the notion of reflection in spiritual practice is. Like with whirling dervishes, there’s a turn towards ecstasy. Or there’s the tradition of poetry that is so painful, or music that touches your emotions with tears. We often associate tears with pain and sadness, but there’s a great relief and beauty that comes with an emotional outburst. I see my own emotional constitution and my work returning to this part of Iranian heritage. This poetic, mystical tradition has helped Iranian people throughout time survive and cope with political tyranny and different personal, social, and political issues.

In my work and life, my point of view is really feminine, too. And I like it that way: the way I relate to politics or history, to poetry. I’ve been very blessed to have subjects that are women. The narratives have always been from the point of view of a woman. So I feel very proud that I’ve remained feminine, both in my work and as myself.”

on grappling with anxiety and loneliness

Those of us who are survivors, immigrants, or others who are constantly negotiating between different places have become masters of coping and adapting. I've often been very sad, but my whole thing has always been to say, I must survive this, I must survive this. I like artists who are vulnerable because they're not afraid of admitting their fragility, which shows in their work. But if I feel too vulnerable, I say no to things like travel because I know I will be really lonely. Learning to recognize when to temporarily pull away to help my own spirit is important, as is remembering that I have a choice: I don't think my work is as important as my mental well-being. I want to be surrounded by people I love, and that love me and make me feel safe.

I'm very disciplined about confronting my anxiety and really do whatever I can. Four years ago, I listened to every lecture that Pema Chödrön has given and read all her books. She's a Tibetan Buddhist monk, and she's incredible. The majority of the time, though, I don't go to a therapist. I deal with my anxiety with physical exercise. I don't meditate, but I really talk to myself: by writing, moving, and just being able to come to a place where I can get a better perspective on the foundation of the fear that is eating me. I think a lot of people meditate or seek whatever transcends them. For me, it doesn't have to do with religion or spiritual practice. It's art, really. What has helped me more than anything, other than my son and motherhood, is my work. It has always been something I can come back to. In the darkness, I find something incredibly creative and really beautiful, and it gives me energy and brings me back up.

on art that inspires her and watching old films

I've taken more inspiration from the lifestyles and approaches to art that certain filmmakers and artists hold. I take a lot of pride in admiring strong, iconic female artists. Frida Kahlo has been a woman I always mention: I take great inspiration from how she did self-portraits in her paintings, who she was, and her idea of feminism. More than anything, Umm Kulthum, who I spent so many years making a film about, has been a true inspiration. And of course, Forough Farrokhzad, who I feel closest to–what happened to her is just so tragic. A lot of filmmakers like Federico Fellini, Abbas Kiarostami, Ingmar Bergman, Andrea Arnold, Lars von Trier, and the master Andrei Tarkovsky really inspire me as well. I've been watching Dekalog by Kieslowski (part one available here) and am just blown away. It is perfect, beautiful. I've enjoyed reading Bordwell too.

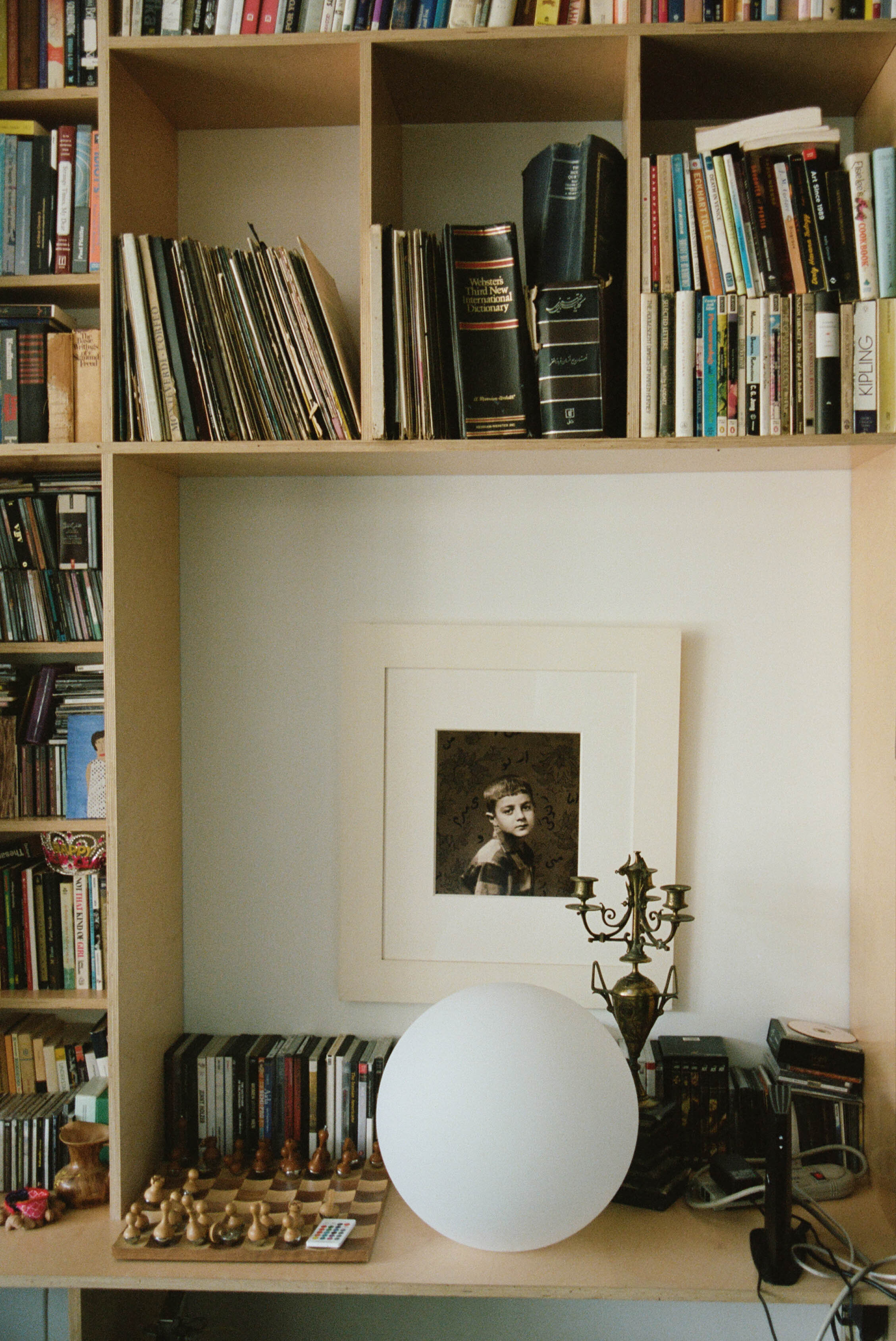

I like to watch movies and to see what other people are doing. We watch a lot of films on our projector, and in upstate New York, we have collections of old master films by important directors. So I'll watch films I like over and over again. I try to read as much as possible, too, when I have the mental space. Some of my favorite books are Never Let Me Go and Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro, My Last Sigh by Luis Buñuel, Zende Begoor (Buried Alive) by Sadegh Hedayat, and Frida Kahlo: The Last Interview by Frida Kahlo. I love The Brooklyn Rail, which we get every month. And The New Yorker. I don't like to read art magazines, so I never do.

on her style

I like the idea of taking care of myself as a stylish, elegant woman who looks good. I like very minimal, simple, mostly black, modern clothes. My style contains a blend of Occidental and Oriental styles that work together to define who I am. I never ever go to expensive, designer stores. Occasionally, I go to yard sales and flea markets where I find really excellent things. I love old things and even collect old Western things. I often wear high necks with a lot of jewelry, which I buy everywhere I go: from Uzbekistan to Tajikistan to Egypt to Iran to Morocco to Mexico.

““I have recently gotten to know Isabella Rossellini since she’s in my upcoming film. As one of the most beautiful women on the planet, she’s had me thinking a lot about beauty. I just love how she approaches age, beauty, and elegance: she’s not self-conscious, and she truly embodies both inner and outer beauty in the way she lives. She’s not afraid of aging, you know, and she’s not afraid of showing it. And I love that she has a lot of humor about her. So, I think that’s what it is: every woman deals with the idea of beauty differently throughout their life’s trajectory. I really blossomed at an older age when I met Shoja at 40. Oddly enough, some people actually look better when they get a little older. Of course, youth is beautiful, but if you’re unhappy and not taking care of yourself, it shows. I think it depends on your state of mind. We all go through the problems vanity and age bring, but I like to see myself within a category of people who believe in elegance and the idea that beauty is not just a physical thing. It is also about what you project as a human being for others to read in you. I saw that energy in Isabella, and I adore her for that.””

on her iconic eyeliner and skincare rituals

It's funny; I always compare my makeup with my art supplies. I only have a few brushes I use with ink and water. I myself don't know how my eyeliner really came about. One day, while still at Berkeley, I just realized I was doing it every day. I see that the way I do calligraphy is the same as how I do my eyes: it is very Nefertiti. Once, on a trip down the Nile in Egypt, we went to some temples, and I was blown away by how so many beautiful paintings were destroyed. The only thing that remained was the gods and goddesses' eyeliner. It looked exactly like how I did it. Part of me thinks it's possible that I came from an ancient culture in my past life, but the truth is, I don't remember myself. All I know is that for most of my adult life, this has been how I look. The eyeliner gets heavier and heavier as I get older.

Occasionally, I also use color on my lips, but the only other thing I do like is using natural oils. I never use perfume, but I am obsessed with lavender; I use Moon Valley Organics’ Lavender Herbal Body Wash, which I buy in New Mexico. I am very particular about what I wash my body with, and I always clean my makeup off really well before I go to sleep. Sometimes, when I'm tired during the day, I refresh my makeup. I clean it off and do it again. And that re-energizes me as a shower would. But, again, it goes back to the idea of the ritual.

shirin’s favorite spots in new york

I don't experiment very much with food or restaurants. I find one or two I like: I like repetition. There's a great bar and restaurant in Soho called Fanelli’s–that's the only thing I miss about Manhattan. The people who work there are artists, and it still hasn't been gentrified, so it's not snobbish or arrogant. Sofreh is fantastic. It's a great privilege to have this kind of food every once in a while, but it's not something I can do very often. I love Sally Roots, and a Mexican restaurant called Paloma’s Mexican Cuisine run by a mother, son, and daughter from Colombia who knows me really well. Lastly, I love dancing at House of Yes. It's so great and scruffy. I think it's becoming more commercial, but I hope they reopen soon. It reminds me of the times we used to go to Danceteria in the old East Village and dance with crazy people with crazy outfits who really, authentically were seeking out a good time.

images by clémence polès