Shop our historical maps

Culture

Allmoge - what is it?

Mar

About the concept of allmoge, and a short guide to the wonderful world of the Swedish allmoge; allmoge furniture, folk art, folk music, the history of the small people and much more. But what does allmoge really mean? Let's find out!

When you talk about omnipotence, what do you really mean? It's been a few years since I started this project, Allmogens, a libertarian and voluntarily funded popular education project where we explore the history and culture of the Swedish Ommogens. But come to think of it, I've never talked about the most basic thing - what is meant by allmoge. I will do that now.

When I think allmoge I think of old wooden furniture and valley paintings, folk songs and handicrafts, wood stoves and timbered cottages, home-baked bread and kams (a staple product of the Åland region). So what do all these things have in common? Well, it's by people, born out of the lives and daily struggles of ordinary people for bread and meaning in life.

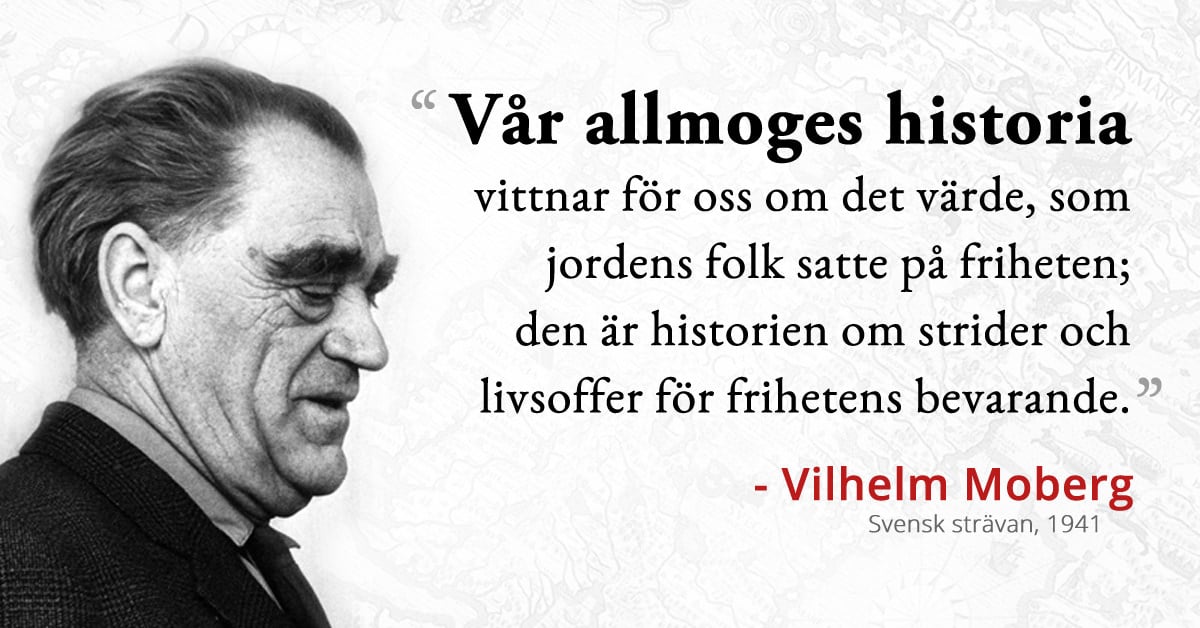

But let's start at the beginning and look at the word allmoge itself. It comes from Old Swedish, and as Vilhelm Moberg tells us in his fine history My Swedish history he used the word "in its original meaning in the Old Swedish of all allowed, the whole people."

The expression "the commoners" also appears in old sources, and then it meant the lower classes, the taxpaying classes as opposed to the more privileged classes. As the urban population formed a bourgeoisie, "allmogen" became more and more associated with the rural population, the peasants and crofters, who accounted for the vast majority of Sweden's population until the 20th century. The latter meaning has survived to the present day, so when people talk about allmoge today, they are most likely referring to the rural population of the old peasant society.

The Swedish allmoge has left many traces behind through the centuries, not least through the customs, traditions and expressions of thought that survive in their descendants - the now living Swedish allmogen. But I would still think that it is precisely the physical remains of our ancestors that most people think of when they hear allmoge. It has in some respects become another word for old-fashioned.

Let's now take a look at a small selection of all the cultural expressions that Swedish people have left behind.

Allmogestil

Whether we are talking about chairs, tables, benches, cupboards, textiles, utensils, windows, doors or even entire houses, "allmoge" probably conjures up a fairly clear image in many people's minds. It's old-fashioned, rural, handy, made of natural materials such as wood, wool, linen, iron, and it is a blissful mix of both very simple creations and the most lovingly crafted works of art.

The "omnipresent style", if we are to call it a style, sprang directly from nature and was created by men for themselves for their own survival and pleasure. It is also a style that is making a strong comeback, as evidenced by the popularity of such TV shows as Ernst, Mandelmann Farm and the Danish One hundred percent peasant.

Why?

After all, in our modern and stressful consumer society, you can drown in cheap, mass-produced gadgets and fill your days with fleeting pleasures. We, today's living Swedish common people, have a standard of living in Sweden that earlier kings could not have dreamed of in their wildest imagination.

Yet so many walk around unhappy, filled with anxiety, or filled with a emptiness that can't seem to be filled by things you find on the store shelf. Something is missing. I think it's partly that lack that makes people long for something else, and then I think it's natural to look back in time. To a simpler time. To something more genuine and meaningful.

Don't misunderstand me. Life for our ancestors was anything but easy. It was a harder life than most can even imagine, with mind-bogglingly long hours, empty stomachs and the constant threat of poverty and starvation beyond the next bad harvest. But that doesn't mean we can't learn and be inspired by times past. It doesn't mean we can't be nostalgic and long for the past. Man get pick the raisins out of the cake. And it's the omnichannel style, the simple, the natural, the beautiful, that's a raisin I want to champion.

The genuine popular the culture of our different landscapes, that is what the Omogestil represents.

Arts and crafts

Allmogens art and crafts have existed since the beginning of time if you ask Per-Axel Hylta, author of the book "Skånsk allmogekonst". I don't think he's exaggerating. People have certainly always wanted to surround themselves with beauty, and folk art is just the kind of beauty that ordinary people surrounded themselves with. It can be expressed in the so-called "carpenter's delight", woodcarving, handicrafts, paintings, etc. What they have in common is that they are things you create with your own hands, often from raw materials you can find locally.

It is precisely this beautiful woodcarving that can be seen everywhere when you look at objects from the old farming community, on utensils such as flax hedges and wicker boards, on kitchen sofas and chairs, on cabinets and beds. Something tells me that people simply had more time in the old days, during the long, dark winters, to make these time-consuming decorations, or rather that they train time. There was probably a lot less competing for your attention back then.

One of the more famous expressions of art is probably the painting of allmogrion, which had a particularly strong centre and peculiar style around Dalarna - the so-called valley paintings with their kurbitsar, but it was also painted freely in Hälsingland, Skåne and many other landscapes.

When did the art of omnibus painting originate? According to Lena Nessle who wrote the book Flowering almond painting (2002), it arose when home fireplaces were improved so much in the 18th and 19th centuries that soot was channelled into the chimney instead of staining the walls. Even before that, beautiful painted bonfires were hung on the walls during feasts, but in the early 19th century, the common people also began to paint their chests, cabinets and furnishings more extensively. Lena Nessle explains:

On coffins, cabinets and furnishings grew flowers and scrolls taken from their own observations in the garden, but they could just as often be influenced by printed so-called coffin letters or the professional church and high-rise painting.

Lena Nessle, Flowering almond painting (2002)

Omnibus costume

More commonly called folk costume or bygdedräkt, this is a traditional costume linked to a geographical region, and in Sweden the details of folk costumes could differ from parish to parish.

What distinguished the clothing of the commoners in the old peasant society was that it was made from whatever material was available locally. This usually meant wool, linen and leather. Silk was expensive, and even state-run abundance regulations in Sweden in the 17th and 18th centuries that prohibited Swedish commoners from consuming certain "luxury goods", including silk, and such government restrictions reinforced the differences between commoners' clothing and that of the upper classes.

The Church of Sweden also had its own rules for how peasants should dress in order to be a good, Christian people. In 1706, for example, maids in Torsö parish in Västergötland were forbidden to wear coloured ribbons (!) in their caps. It was too daring, I guess.

Folk costumes were originally the historic clothing of the common people, worn all year round before the Industrial Revolution, but increasingly shelved in favour of factory-made clothing as society modernised in the 19th century. Folk costume has remained in the wardrobe and has been brought out at festivals, and during the 20th century interest in it has come and gone among Swedish folk.

Allmogemusik

Swedish folk music is the music that originated and was passed on by the common people, where it was played for both everyday and festive occasions. Folk music has many roots and includes everything from the musician traditions and folk songs to traditional folk music and rearranged hymns.

The variation in folk music is great and could differ between different parts of Sweden, between regions, parishes and even villages. The music is taditionally aural, i.e. instead of notes, the music was passed on through listening and imitation.

Poppy music also belongs to the music of the Ommogens. It was the music of the Swedish pastoral culture, where the music was used to attract animals and to communicate between farms. The music could be performed on a ram's horn, lurs and via calls, all of which can be heard from great distances.

Kulning is another name for the call of the willow music, which has received a lot of attention in recent years thanks to Jonna Jinton's magical cults from Ångermanland:

Some of my favourites in Swedish folk music, whose tones are often heard here on the farm, are the singer Sofia Karlsson (e.g. the album Black ballads with interpretations of Dan Andersson's poems) and the musician Thomas von Wachenfeldt (also don't miss the musician Erik Svansbo's youtube channel). Wardruna is another favourite, though not Swedish folk music but rather a bearer and interpreter of an older Nordic musical heritage. If you like old Swedish poems by giants like Heidenstam, Karlfeldt and Fröding, you should not miss Lars Anders Johansson's album Renaissance.

If you want to hear more about folk music, listen to Thomas von Wachenfeldt's podcast Trad-Podden, where you will hear about both dead and living fiddlers and learn more about the traditionalist part of Swedish folk music.

Allmogekost

As I have written in more detail in the article What did people eat in Sweden in the past? in Sweden, right into the last century, people ate what nature could provide. In the old peasant society, people lived off the land and the forest, and from there they used the traditional raw materials that make up the common diet. In years when the soil did not produce a good harvest, bark and lichen often had to be added to the bread, and in such years hunting and fishing became all the more important. Most recently, in 1867-1869, during the great Norrland famine, people starved to death in northern Sweden due to crop failure and starvation. But in the years when the harvest was good, there was no need to go hungry.

Today we talk about Swedish cuisine, i.e. the food culture and traditions that exist in the country of Sweden, but in the past you could not speak of a specifically Swedish cuisine. Our Swedish culture has many roots, and food culture differed between regions and landscapes depending on what the forests, waters and fields had to offer the local people. In the north, more barley was grown, while rye and wheat were more common in the south. But one thing that was embraced with equal devotion across the country was the potato... perhaps mostly, of course, because the commoners found out that potatoes could be used to make brandy.

From Halland there is a description from 1796 by the provost Per Osbeck, who says this about the food of the common people:

The people here eat 5 times a day, breakfast, dinner, supper and supper. Breakfast is a drink of brandy if available. Daver consists of herring and drink with milk mixed in. Dinner: cabbage, peas, soup along with meat and pork or what can be accomplished; evening spirits. Evening meal mostly porridge, one evening boiled, the other roasted.

Fish, cabbage, peas, meat, pork, porridge, dairy products and spirits. Add some cereals, potatoes and other root vegetables and you have the traditional ingredients for a healthy, Swedish home cooking.

The word home cooking comes after housekeeper, owner of a small house without land. The term was originally used to describe simple and cheap food eaten in the countryside.

What dish pops into your mind when you hear that word? What flavours can you taste in your mouth? Meatballs, mashed potatoes and lingonberry jam might be one of the most well-known dishes, although falukorven, for example, is more genuinely Swedish. For me, at least, it's my grandmother's kams, or palt as it's called further north. Kams with lingonberry jam and butter.

Allmogekunskap

A clearer designation of the knowledge around which the everyday life of the Ommogens revolved is survival skills. Because that's what life used to be about in the North. Surviving the next winter - and being able to afford to pay taxes to the bailiff and priest. And they got pretty good, the commoners, at surviving.

The amount of skills and knowledge of nature that our ancestors mastered is impressive to say the least. Those of us with roots in the North are descended from people who survived thousands of winters in our harsh, unforgiving climate. No electricity. No municipal water. Without sewage. Without geothermal heating. No ICA. No cars.

They knew how to hunt and fish in summer and winter, cultivate the land, care for animals, harvest crops and meat, use medicinal plants, brew beer and distill spirits, build houses, lay bark and chip roofs, weave textiles and tan hides, survive in the wilderness, make weapons for hunting and self-defence, build timber houses.

All this was possible for every other person in the past. Today, fewer and fewer have mastered it. The situation is so bad that municipalities are starting to run into problems when it comes time to renovate old listed buildings, both in terms of getting timber of good enough quality and people with the skills. One municipality I read about, for example, was having trouble finding someone with the knowledge to lay traditional shingle roofs (hint: call me next time, I can and will help).

Of course, it's only natural that knowledge and skills that are no longer needed are forgotten, leaving room for new skills, but the question is whether we shouldn't hold on to those survival skills for a while longer. Not only for the practical value, but also for the pleasure of it, and because it gives meaning and a sense of continuity to maintain that invisible link to those who lived before us.

Given the strength of outdoor life among Sweden's general public, it makes sense to know how to get around in the woods, whether you're young or old. I've also seen an explosion of interest in "bushcraft" in recent years, and "bushcraft" is just an English word for the ancient knowledge of the ancients about how to save themselves in nature.

I myself remember when I was in middle school how we had a "Stone Age Day" when we had to cook fish in cooking pits and build a hut out of felled trees (albeit historically incorrect, it turned out later). It was one of my favorite days at school. I don't know if that day still exists at school, but I'll certainly make sure my kids can sort themselves out in the woods when they get a little older - no matter the weather or the season. It's a good deal better time spent than having them stare into a digital screen, which they will do for far too many hours of their lives regardless.

Interest in "prepping", i.e. crisis preparedness, is also constantly increasing - much because of an increasingly unsettled world situation, but also just because we are so disconnected from nature in today's high-tech and disruptive society. Our ancestors did nothing but "prepare", every day, all year round, just to survive the next winter. In that way, I think those who lived before us in Sweden are good role models and also good teachers for those of us who are interested in growing our own food and rediscovering that close relationship with nature that the common people had not so many generations ago.

Allmogekultur

All of the above together make up the Swedish culture of the commons, the peasant culture, this great, beautiful tapestry with threads woven in from all times and directions. This culture still lives on among Swedes today and is perhaps most evident in our festivals and meals - not to mention in all the beautiful old timber-framed houses scattered across the country. But it is also evident in the way we think and act in a social context.

Who knows, perhaps it is in the old peasant society that we find the origin of the Swedes' avoidance of conflict, of our strong culture of consensus, and of the fact that we never sit next to another person on the bus if there are seats available elsewhere. Who knows? This is just one reason to learn more about your history and culture. Through history you can gain an understanding of the times you live in. Through history you can get to know yourself.

The culture of the commons also includes all the traditions and customs of the old farming community or even older ones, with their harvest festivals and other celebrations linked to the changing seasons.

One can also, or even mainly, speak of different cultures linked to the landscapes. There is a Skåne allmoge culture, a Jämtland culture, a Gotland culture, a Bohusland culture, and so on. All beautiful, all worth remembering and passing on to future generations.

Allmogens history

Last but not least, Swedish allmoge has a history all of its own, history of small peoples. "Sweden's history is its commonwealth" was Vilhelm Moberg's message with the history he devoted most of his life to writing in his books, and which he wrote down in the years before his death after 60 years of reading on the subject. Moberg's thesis is a rebuttal to Erik Gustaf Geijers (1783-1847) winged thesis that "Sweden's history is the history of its kings".

Allmogens history is the people's history of themselves, which Moberg believed had been withheld from them throughout history. Instead, it was the history of kings, the state church and the many wars that were taught in school desks. The history of the Swedish state.

The history book taught me how the Swedish armies were set up at Breitenfeld, Lutzen and Narva, but gave me hardly any knowledge about my ancestors, who were part of the armies themselves. Nor did other school textbooks on Swedish history tell me what life had been like in the past for the people to whom I belonged. Peasants, soldiers, servants, crofters and cottagers had thus achieved nothing worth remembering, because they were not allowed to be included in history.

Vilhelm Moberg, My Swedish History vol. 1

Moberg talked about how schoolbooks gave him a "distorted view" of his country's history, not through what was in the books but through what not said in the judgment.

He missed the commoners "who had sown and cleared the fields, those who had cut the forests, cleared the roads, built the castles, the royal estates, the fortresses, the castles, the towns, the cottages." He missed "those who paid the taxes, who paid all the priests, bailiffs and officials."

He missed "the numbered men of the armies, who died in foreign lands for the fatherland, their wives waiting at home." He missed "the class of servants, for whom a special law, the Servants' Statute, had applied." Nor did he find the vagabonds, "the so-called defenceless, who did not own land, house or home."

He also missed the nearly one and a half million Swedes who, under duress and oppression, or driven by a sense of adventure, left Sweden to cross the great ocean to the west - to America.

These were the people Vilhelm Moberg wanted to tell us about, and he did so in many of his books. Their story is very much the story of human rights, property rights and the struggle for freedom. A struggle for bread, but also a struggle to keep the fruits of one's labour and the right to think, speak and live free.

This is the story that some of our most beloved Swedish writers of the 19th and 20th centuries spent many years of their lives writing down. Men like Anders Fryxell, August Strindberg, Alfred Kämpe, Fabian Månsson and Vilhelm Moberg wrote it down because they felt it was worth preserving for future generations.

It is also the story that we at Allmogens works to preserve and bring to life, including by digitising and highlighting old historical artefacts, articles, poems and songs, etc., but perhaps even more popular is Allmogens instagram feed and Youtube channel about the history and culture of the Swedish Ommogens.

Vilhelm Moberg mentions in the introduction to My Swedish history how, even after a short walk through history, he felt a sense of wonder about his own history that only grew stronger. He asked himself:

How has this people, whom I seek to follow through the ages, survived all the evils that have befallen it, all the wars it has endured, all the disasters that have occurred, the plagues and famines that have recurred almost regularly, all the distress, all the oppression, all the hardships - how has it managed to survive all this?

Vilhelm Moberg on the history of the Swedish Ommogens in My Swedish History vol. 1, p 17

Well, after I started to learn about my own story as an adult, I can say that it is nothing but a fantastic story, Sweden libertarian history. And I've only scratched the surface so far, so if this is your first visit to Allmogens.se, you're very welcome to join me on this journey as we rediscover Swedish history together.

Do you want to contribute to the preservation of our history and the memory of the Swedish allmogen and pass it on to future generations? Then you are welcome to become a member of Allmogens Friends.

Subscribe to YouTube:

If you appreciate Allmogens independent work to portray our fine Swedish history and Nordic culture, you are welcome to buy something nice in the shop or support us with a voluntary donation. Thank you in advance!

Support Allmogens via Swish: 123 258 97 29

Support Allmogens by becoming a member

Support Allmogens in your will

Popular

Allmoge - what is it?

The slaughter of the almages on Helgeandsholmen 1463

How to renovate old windows step by step

Smokestone (Eye 136)

The plague in the Gullspång river

Culture

25 March 1644: Massacre of Scanian peasants at the Battle of Borst

Speech on Swedish Flag Day

Small bluebell voted Sweden's national flower