Detail of the Postsparkasse facade top.

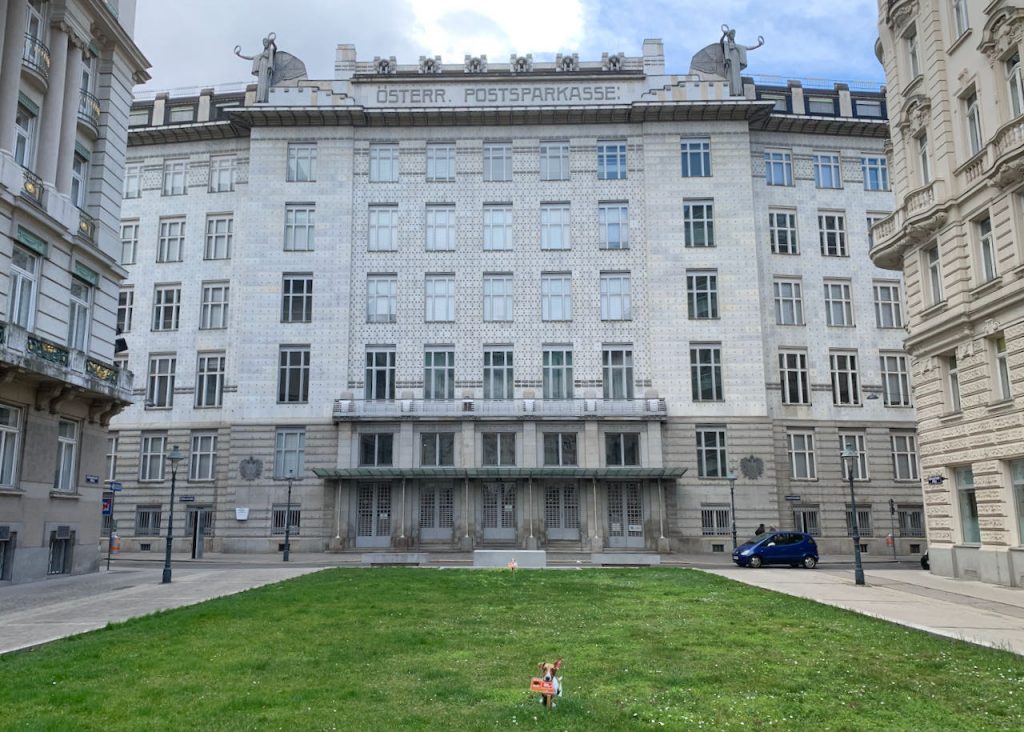

Self-guided Walking Tour: Otto Wagner and the Postsparkasse

Janes Walk 2015 Otto Wagner Tour led by Andrew Nash in front of Postsparkasse Vienna

By Andrew Nash, originally prepared for Janes Walk Vienna 2015. Other self-guided walking tours:

Ringstrasse 1, Otto Wagner Tour, Otto Wagner and the Vienna Stadtbahn, Ringstrasse 2.

Postsparkasse – Otto Wagner, 1904-06 (front building) and 1910-12 (back building)

Otto Wagner (1841-1918) is recognised today as one of the pioneers of Modern Architecture. He was a leader in the effort to create buildings that were highly functional and whose design reflected the new building materials.

In 1903 Wagner won the competition to design an office building for the Postsparkasse.

At the time most monumental buildings were historical, modelled after Roman bathes or Baroque palaces. The Ringstrasse is full of examples, including the (former) War Ministry building across the street. Wagner’s goal was to create a monumental building in the modern style he advocated in his books and teaching.

Luckily for Wagner, the Postsparkasse (German for postal savings bank) company wanted their new headquarters to project a modern image. The building is the first modern office building in Vienna and one of the first in the world.

Who was Otto Wagner?

Otto Wagner was born on 13 July 1841 in Penzing, a suburb of Vienna at the time. He attended architecture school in Vienna and Berlin. He was a student of August von Sicardsburg and Eduard van der Nüll (Architects of the Staatsoper, 1861 – 1868).

Musikverein by Theophil Hansen

Early in his career he worked with the architect Theophil Hansen, serving as construction manager (Baumeister) for Palais Epstein (1868). Hansen was a family friend and one of the most famous Ringstrasse architects. His buildings include the Parliament, Musikverein, Vienna Borse, Deutschmeister-Palais (Palais Erzherzog Wilhelm), and Palais Ephrussi.

One of Wagner’s best clients was himself. He served as developer of many apartment houses throughout Vienna generally living in them for a few years before moving on to a new project. Key projects and life events include:

1879 – 1881 – Decorations for Imperial events – professional recognition.

1881 – Divorce from first wife, marries Louise Stiffel, governess of one of his children.

1883 – 1884 – Österreichische Länderbank building – very well received.

1893 – Wins competition for Vienna Regulierung Plan (city planning concept).

1894 – Appointed artistic director for Stadtbahn project (city railway).

1894 – Appointed Professor at Academy of Visual Arts (Bildende Kunst).

1895 – Publishes first edition of Modern Architecture. Wagner understood the importance of media and photography. This was especially important for an architect with new ideas and for whom most of his projects were unbuilt.

Facade of Linke Wienzeile 40, Majolikahaus.

1898 – Linke Wienzeile Apartments – official break from conservatism to secession.

1904 – Postsparkasse

1905 – St Leopold’s church am Steinhof

1911 – Publishes Unbegrenzte Großstadt Wien (unlimited big city Vienna), a proposal for modern city planning.

1918 – Death of Wagner.

What is Modern Architecture?

Generally speaking, Modern means up-to-date or current. Unfortunately, the term Modern Architecture is used to refer to a style (sometimes called International Style) developed in the period starting around 1890 and extending into the mid-20th Century. So, while a building constructed today is modern, its style might not be “Modern”.

The name Modern may well have been chosen because the style represents a very clear break from the more traditional history-based style of building. This break, as with earlier stylistic breaks, happened when builders took advantage of new technology to construct new types and styles of buildings. For example, Gothic architecture was made possible by creation of the flying buttress.

The Postsparkasse entrance is straightforward and functional glass and iron.

Furthermore, this was a period of rapid and drastic change: new technologies, the industrial revolution, democracy and the decline of empires, travel and increasing availability of luxury products. Many, Wagner included, believed that art and architecture, which at the time was based on historic styles, must change with the times.

Finally, when theorists wrote about Modern architecture, they often focused on “universal truths” rather than stylistic rules. For example, Wagner believed nothing could be beautiful unless it was functional (his motto was: Artis sola domina necessitas … Art has only one mistress, necessity). Perhaps then, the theorists believed that Modern Architecture, so defined, would become a term that could be used to describe all future styles.

What is a modern building?

Wagner and his fellow modernists wanted to develop a new architecture that reflected the new possibilities of engineering, materials and technology. For example, they should reflect the full possibilities of new materials like iron, steel and reinforced concrete.

Modernists believed new buildings should not look like old buildings. But what does this mean in practice? To modernists the building’s:

- design should be functional and honest,

- materials should be visible and contribute to the building’s aesthetic qualities, and,

- structure should be made visible – it should show the structural possibilities made possible by the *new* materials.

Postsparkasse, Vienna by Otto Wagner 1903.

Postsparkasse as a Modern Building

You can see these principles of Modern Architecture in the Postsparkasse building. Look particularly at: visible elements of structure like the iron, highly functional design elements like large windows in a flat façade, and the overwhelming presence of the iron nails holding the marble cladding to the building.

The building was constructed by bolting a thin cladding of high-quality marble to the structure rather than using the traditional stone construction methods commonly used at the time. The nails call attention – make visible – this construction technique. They also, by making the building look like a treasure chest, communicate that the Postsparkasse is a safe place to put your money!

The clean, clear and functional design of the Postsparkasse by Otto Wagner is a monument of Modern Architecture.

In his book Modern Architecture Wagner discusses the cost savings and faster construction possible by not using the traditional stone construction methods.

Most importantly, the Postsparkasse is a highly functional office building. It was designed for about 2,000 workers. There were special entrances for workers directly into the garderobe, and the garderobe locker key fit the employee’s desk too!

Inside it was clean and well lit (notice the windows – large, no frames, flush with façade). The building’s interior layout is extremely functional … short and efficient paths through the building, sufficient number of bathrooms, etc.

Interior colours and furniture were also designed by Wagner and followed a clear hierarchy from top managers down to workers and customers.

Throughout the building materials were used that could be easily cleaned– important given how dirty the city environment was at that time. Example: aluminum does not rust.

Hygiene was an important theme for Wagner in all his buildings. This is very understandable given how dirty cities were at the time. Cleanliness was a very modern concept in keeping with the (then) newly developing technology. New materials and technology made it possible to be clean.

Postsparkasse as a Monumental Building

Postsparkasse, Vienna by Otto Wagner 1903.

But, Wagner saw no need to change what is still important: the Postsparkasse was intended to be a monumental building and therefore respected traditional monumental form.

“Wagner did not want to have a radical break from traditional building, as many later functionalist architects (1920s) did, but wanted to update it by a consistent integration of purpose, material and construction into the machine age that has long since begun.” (Wien Museum, Otto Wagner Exhibition Catalogue p. 377)

The exterior massing and high quality of materials clearly conveys that this is a monument – meaning important – building. The interiors also combined new materials with traditional monumental forms. For example, the teller’s lobby is built with iron construction, sky lighting, and aluminum … in the form of a basilica church.

Wagner’s Architecture in Schizophrenic Vienna

Vienna was a very schizophrenic place at the turn of the Century from 19th to 20th. On the one hand cutting edge arts and science: Freud, Klimt, Kraus, Wagner, on the other the establishment anchored by the extremely conservative Hapsburg Court.

The Hapsburg’s were especially conservative in their architecture. They wanted an architecture that clearly conveyed their power. Their favoured style was Baroque as expressed in most of their buildings from the mid-1800s until the end of the empire.

In fact, the Hapsburgs filled the Ringstrasse with monumental buildings in the Baroque style most impressively the Neue Burg (new palace), the Kunsthistorische Museum (art history museum) and Naturhistorische Museum (natural history museum). See Ringstrasse tour.

Compare the Kriegsministerium building with the Postsparkasse.

Compare and Contrast: War Ministry – Ludwig Bauman, 1909-1913

And, it’s possible to do a quick compare and contrast just by looking across the Ringstrasse from the plaza in front of the Postsparkasse.

The Kriegsministerium (war ministry) building was build a few years after (!) the Postsparkasse in a very orthodox neo-baroque style. The architect was Ludwig Bauman, a friend of the extremely conservative Heir Apparent, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (later assassinated in Sarajevo, starting World War I).

A competition was held in 1908 to design this building and it’s fascinating to compare Wagner’s proposal to Bauman’s design. Wagner’s very modern design extended concepts from the Postsparkasse. In contrast, the Kriegsministerium was already viewed as old-fashioned when it was completed.

One of the fun things about leading tours is that often your guests add interesting information. Here one of my guests mentioned how dreadful the interior of the Kriegsministerium was for working (it’s still used by the Austrian government). Many of the working spaces are dark, claustrophobic and dysfunctional. The Postsparkasse’s working spaces are exactly the opposite. Maybe that’s why Austria lost the first World War but the Postsparkasse existed well until the end of the 20th Century.

Visiting the Postsparkasse

Design for Kriegsministerium building by Otto Wagner 1908 Vienna from Otto Wagner exhibition at Wien Museum.

Until several years ago the Postsparkasse was still used as a headquarters for the bank that took over from the Postsparkasse (BEWAG). It was possible to visit the main banking hall and there was a small museum, with original furniture (designed by Wagner) and drawings (including Wagner’s design for the Kriegsministerium).

Unfortunately, the bank had problems, merged with another bank and moved out of the building. For several years it was unclear what would happen to the building. Incredibly there was some speculation that this monument of Modern Architecture might be torn down (!!!). Luckily, the federal government purchased the building and is now renovating it to be used for several universities including one specialising in art. With luck we’ll be able to visit the building again in the near future.

Comments and Questions

The Postsparkasse building and Otto Wagner are complicated subjects and I am not a specialist, only someone interested in architecture history and Vienna. Please send any suggestions for improvements or questions.

0 Comments