This is a personal, largely architectural speculation. I am not an art critic or a historian. I did study art with Richard Hamilton. For a year… the comparisons that I make to the works of other artists arise out of my accidental, biographical awareness of those works, brought about by incidental proximities driven by a fascination with their architectural and sexual implications. Smart’s work on show at TarraWarra Museum of Art (Master of Stillness: Jeffrey Smart paintings 1940–2011) led me to reveries on places and my personal existence relative to them. Perhaps this is a Through the Looking Glass fantasy, as Smart himself pretends in The Construction Fence (1978), in which it seems the young woman flees from all that he has set out to reveal to us.

Jeffrey Smart, The construction fence, 1978, oil and acrylic on canvas, 88.5×228.4 cm.

Image: Gift of Eva and Marc Besen 2001, TarraWarra Museum of Art collection

Though, or perhaps because, my concern is with what these works may tell us about contemporary places, I begin with displacement. This, in my exploratory ideograms, is the conceptual model that I see everywhere in these works. In a preliminary notation and in the final ideogram, I drew the profile of the artist looming large on the right, looking left, but veiled from sight. In the middle ground there is a homunculus. The gaze of the artist becomes palpable as this figure stares unmoved at the scene that the artist is “seeing into existence.” This detached observer icon represents for me the pose that the artist signals to us: displaced and masking the ardent sensual and erotic gaze that occasionally shows, but mostly at a remove. A seductive figure is seen through a frame, desired, depicted, but partly hidden (San Cataldo 1, 1964). Ostensibly we are focused on the bright space demarcated by four poles – one green, one blue, one red, one yellow – between changing blocks “E” and “F,” but reflected light faintly lifts a lissom nude into view, a torso framed in a change room doorway, a dark interior beyond. The cool, platonic, abstract gaze switches to the flickering glances of desire …

As Dave Hickey, an American critic and theorist, writes: “… the erotic and aesthetic potentials of images derive from … the same rhetorical language and iconic display … and beyond the proclivity of the beholder there is no way to sort them out.” (The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty , Los Angeles: Art Issues Press, 1993, 55.) Consider these notes on a sketch by Smart (on the wall to the right of the entrance to the galleries): “On the left: verticals deep yellow. Wall is mid green. Orange light. Figure … walks (across) windscreen … white shorts …” Simple notes, but “white shorts” signals, as the pictures attest, an erotic charge.

Irresistible to me as a telling precedent to Smart’s depiction of desired figures is the 1930 painting by Edward Burra, who had an obsession with sailors, Sailors at the Bar . The men are seen through a doorway that frames them but also protects the observing painter from direct involvement, or is it from the appearance of direct involvement? Possibly, given the conflicted context for homosexual desire then as now, it is both. This is what I mean by displacement.

Jeffrey Smart, The gymnasium, 1962, oil on composition board, 63×77.2 cm.

Image: Gift of Eva and Marc Besen 2001, TarraWarra Museum of Art collection

Paul Cadmus (1904–1999) in his 1952 painting Finistère makes these conflicted gazes somewhat more explicit, but not entirely. Here on the harbour two young men rather archly signal their erotic interests but pointedly do not catch each other’s eyes. In the background people innocent of these desires ignore the silent drama. The gaze of the artist and his erotic interest is completely evident. The main figure and the surely redundant phallic symbols are in the middle of the front of the picture plane. Both young men could be competing for his, the artist’s, attention. Hence the archness. The artist pretends to observe, but has made this drama for his own edification (and that of his knowing friends?). This painter situated himself in the drama, aroused. Smart could be direct, but he used framing and placing, not symbols (Rushcutters Bay Baths, 1961). The framing against many doorways is itself erotic, suggesting many sites for the playing out of (then) illicit desires.

For me there is an eidetic charge here, one that cuts to personal recollection. These paintings often jolt us into eidetic recall, but clearly that recall will depend for each of us on our personal histories, on the ways in which we have forged our mental space. I was taken as a small boy to be taught how to swim at the Hillcrest Baths, a vast, cream brick Babylon of swimming and sunbaking. Howling, I was thrown into the water by a retired Olympic coach whom my mother trusted utterly, but who to me was an ancient, fearful crocodile. I sank like a stone in protest and taught myself to swim in a farm dam. Having mastered the rudiments of the art, I was allowed to cycle to the baths, pass my pennies over the ticket counter above my head and, after showering, swim. Here were many mysteries on display, especially boys with muscles and bulges in their jersey swimming trunks. Somehow I knew not to reveal this interest or talk about it at home. But goodness, I was as fascinated as Paul Cadmus. Years later, as an adult, I made a visit to this towering Babylon of a building, with its acres of shimmering water and strolling young gods, only to find that it was a tiny municipal bath and that the ticket booth was no vast monument to bathing pleasures, just a little brick booth.

Smart, in his Coogee Baths, Winter 1 (1961), is altogether cooler, more displaced than Cadmus, more like my strangely discreet young self. In this painting of a scene so reminiscent of my early memory of Hillcrest Baths, we are presented with acres of deck, primary colours on an angle and framed views of a cliff surmounted by the graphic remnant sun, recalling Ed Ruscha’s self-definition as an “abstract artist who deals with subject matter” (Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas , 1963). This is what the picture seems to be about until we notice that in Smart’s “sweet” spot, framing the square that begins a golden rectangle or Fibonacci spiral, he has placed a young bather, towel wrapped over his shoulders, lost in reverie. There is no hint that this bather is aware that he is being painted, being stared at. But there is no doubt that the placement is very deliberate. At this moment the veil drops and I think we see the artist’s perhaps less than frank, comparatively removed or displaced gaze. Nikos Papastergiadis points out that in this picture one part of the railing at the edge of the deck, the most prominent part, is missing. This becomes relevant later in this speculation.

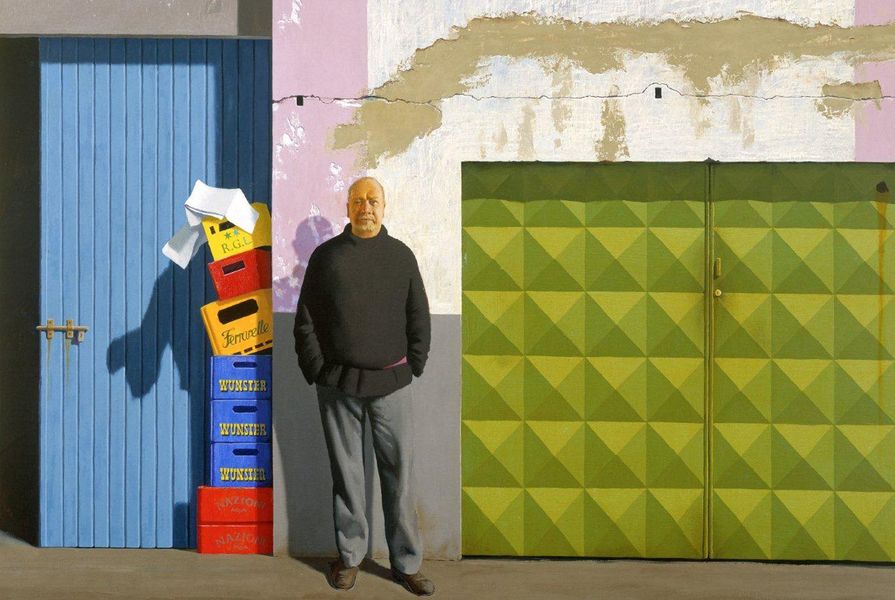

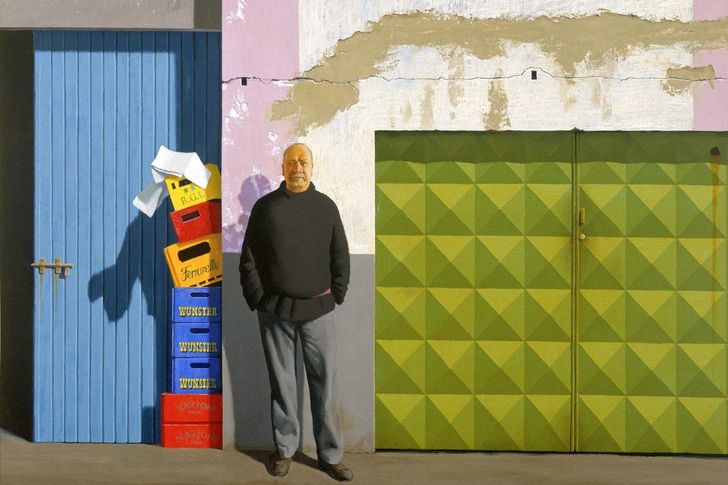

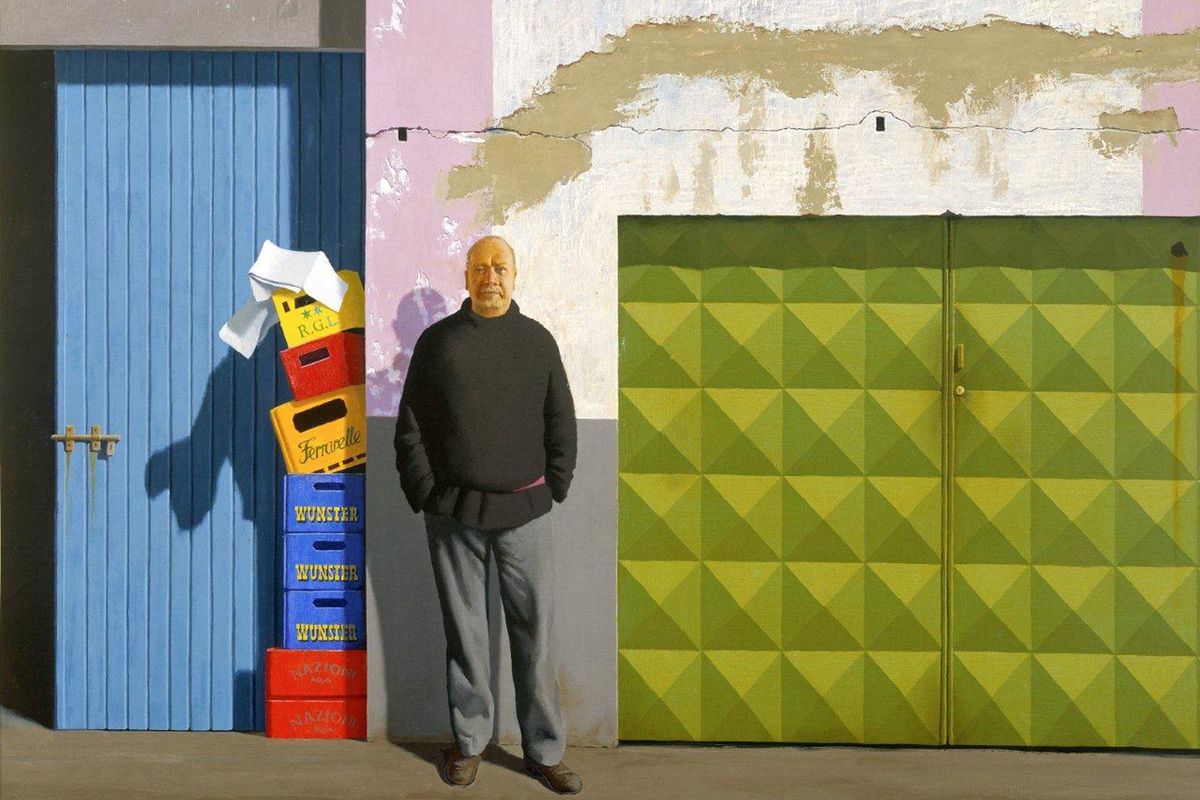

Jeffrey Smart, Self-portrait at Papini’s 1984–85, oil and acrylic on canvas, 85×115 cm.

Image: Private collection

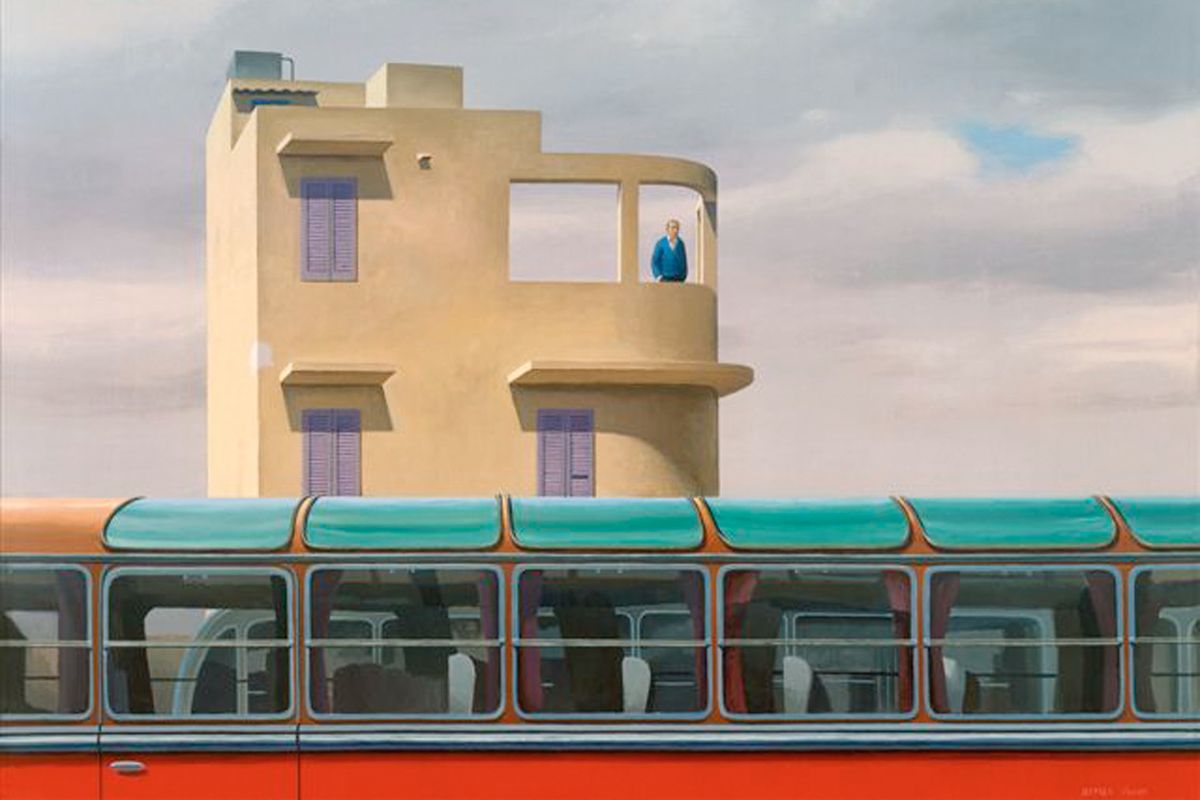

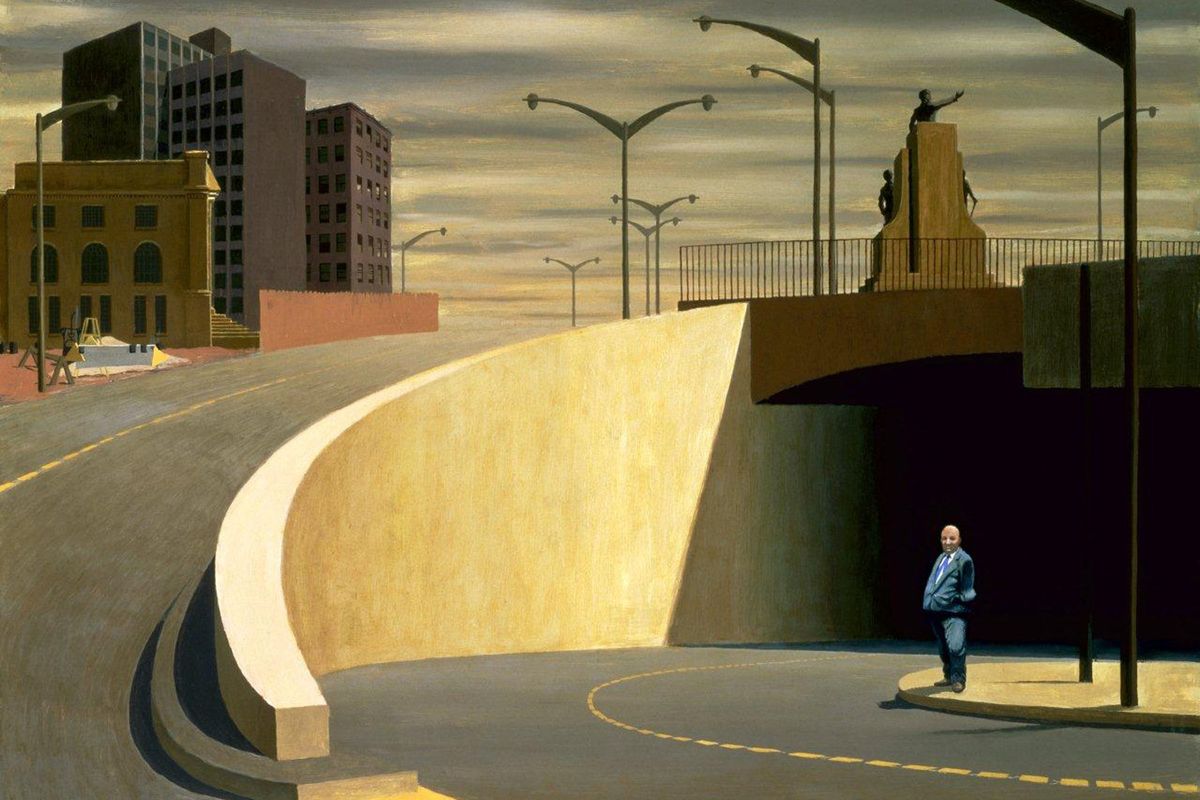

This “beholder” reads the tension between the abstracted displacement of the place and the charged placement of the figure as a metaphor for a wider condition of estrangement and engagement with place that prevails in the rapidly churning spatial configurations of the contemporary city. These are cities in which explosive growth or population collapse have made most of us share a sense of being displaced, made us as literally marginal as gay desire once made, and in many places still makes, homosexuals. Here Smart, I think knowingly and not merely incidental to a veiled desire, had his eye on something profound. Explosive development rips cityscapes apart, churns through familiar urban fabric, sets place adrift, collides with traditional forms of streets, terraces, squares and circuses, and sets up uncanny juxtapositions that are often – rightly – regarded as quite literally alienating.

As in Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965) or, as Scott McQuire acutely observes, in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Eclipse (1962) or in the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, massive new developments remove our familiar cities from us. I recall that as a recent migrant to Melbourne I would meet my then school-going children in a cafe on Exhibition Street every Saturday for lunch. Café Niagara (or was it café Sinatra?) was spelled out in neon on the window. We got to know the staff, the menu and the slightly grungy interior. It seemed to have been there forever, seemed that it would be there forever. And then one day it was gone and during the space of a week it had been demolished. I experienced an acute sense of loss and the city swirled back into that plain, impenetrable set of surfaces that Paul Carter (“Migrant Musings: Christmas in Brunswick,” Agenda, 1992) captured so well in his account of a migrant’s anaemic view of a new city, a view of ineluctable thinness, of mere surfaces, planes with no history. Smart is here with the migrant’s eye, an exile because of his innate desires, then considered deviant. Later he is here because he became a migrant in Italy. In his Self-Portrait at Papini’s (1984–85) he situates himself in front of a wall of peeling fragments of posters, of layers of paint and plaster, as if claiming this very relationship to surfaces and their hidden depths.

So I vehemently disagree with Robert Nelson’s characterization, in his review in The Age (9 January 2013), of this interest in surfaces and planes as the consequence of a lazy lack of craft. Explosive growth is accompanied by a diminution of detail, a flattening of surfaces, a literal thinning out of architectural intent. Look at City Road in Melbourne. All those towers share a dim resonance with Mies van der Rohe’s Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, but at what a remove! How many times displaced and degraded! So dim the resonance! My argument is that being doubly an exile, firstly in his birthplace and because of the suppression of his sexuality, secondly as a migrant to Italy, Smart was tuned in to the edges of surfaces, had a fascination with displacement in all of its modes.

All of this Smart famously observed and visitors to the TarraWarra exhibition were surrounded by exclamations of recognition for the acuteness of the urban anomie he captured. Smart knew that we are intensely personal in our inhabiting of cities, that we can find a universe of meaning in the crumbling posters layered on a wall – a palpable suggested history that we grasp at, recognizing in its dumb layering the way in which we layer our personal lives onto places. This is a formidable painterly act and Smart signalled it to us very clearly. He could do the Arcadian, the lush and the deep landscape. The train wagons in Container Train in Landscape (1983–84) run through an Arcadian Australian landscape as a string of flat primary colour frames and then – in a gap – they frame a deep landscape depiction that is knowing and that says to us: “My interest in these flattened surfaces is not trivial.”

A video of public the lecture and question time.