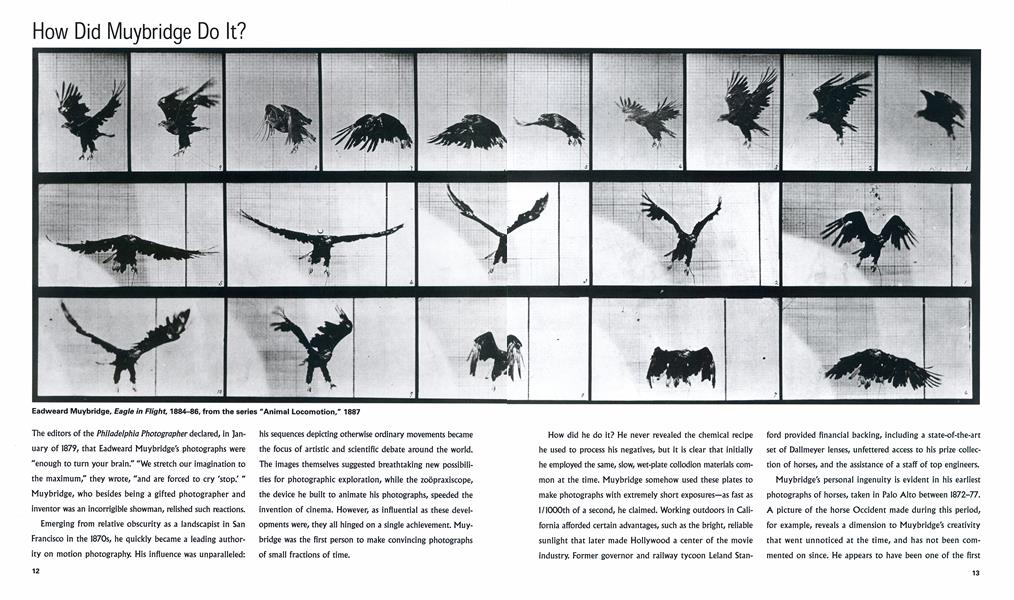

How Did Muybridge Do It?

The editors of the Philadelphia Photographer declared, in January of 1879, that Eadweard Muybridge's photographs were "enough to turn your brain." "We stretch our imagination to the maximum," they wrote, "and are forced to cry 'stop.' " Muybridge, who besides being a gifted photographer and inventor was an incorrigible showman, relished such reactions.

Emerging from relative obscurity as a landscapist in San Francisco in the 1870s, he quickly became a leading authority on motion photography. His influence was unparalleled: his sequences depicting otherwise ordinary movements became the focus of artistic and scientific debate around the world. The images themselves suggested breathtaking new possibilities for photographic exploration, while the zoopraxiscope, the device he built to animate his photographs, speeded the invention of cinema. However, as influential as these developments were, they all hinged on a single achievement. Muybridge was the first person to make convincing photographs of small fractions of time.

How did he do it? He never revealed the chemical recipe he used to process his negatives, but it is clear that initially he employed the same, slow, wet-plate collodion materials common at the time. Muybridge somehow used these plates to make photographs with extremely short exposures—as fast as 1/1000th of a second, he claimed. Working outdoors in California afforded certain advantages, such as the bright, reliable sunlight that later made Hollywood a center of the movie industry. Former governor and railway tycoon Leland Stanford provided financial backing, including a state-of-the-art set of Dallmeyer lenses, unfettered access to his prize collection of horses, and the assistance of a staff of top engineers.

Muybridge's personal ingenuity is evident in his earliest photographs of horses, taken in Palo Alto between 1872-77. A picture of the horse Occident made during this period, for example, reveals a dimension to Muybridge's creativity that went unnoticed at the time, and has not been commented on since. He appears to have been one of the first photographers to use panning to capture motion, following the subject with his camera to reduce its movement relative to the plane of the negative. While this resulted in photographs with blurry backgrounds, it also enabled him to produce pictures in which his moving horses were relatively sharp. This technique, though of limited use in still photography, ultimately became one of the defining characteristics of cinema, which he helped to invent.

Although he later abandoned this panning technique, Muybridge excelled at tracking motion. Even using a series of cameras, as he often did in his later work, it was tricky to gauge the velocity of a subject, and determine where to place the cameras to obtain the best results. His sequence of a swooping eagle, made during his residence at the University of Pennsylvania from 1884-86, is a masterwork of anticipation and timing. It not only shows a bird hurtling through space at a changing rate and altitude, it also captures the subtle pivot of the animal's body at the nadir of its descent.

Despite his virtuosity, Muybridge always suffered from credibility problems. One of the most famous of his horse photographs, Occident Trotting at a 2:30 Gait, purports to be a photograph of a horse's movement frozen in time. Yet it is not really a photograph. Although sold as an albumen print, it is actually a copy of a drawing now in the collections of the Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, itself presumably copied from an indistinct photograph unsuitable for publication. Muybridge acknowledged on the mount only that, "The picture has been retouched, as is customary at this time with all first class photographic work." The veracity of Muybridge's photographs are often questioned. In a sequence such as the Batsman, for example, one must rely on Muybridge's account of how it was made. Nothing about the picture itself indicates time elapsed. Yet human subjects are easy to direct—can we be sure that the man in the picture is really swinging a bat at full speed, or has he slowed himself down to enable himself to be photographed more easily? Were each of the frames made in a single session, or were they assembled from separate attempts? Were there additions or deletions? In short, could Muybridge be trusted?

Even in Muybridge's day, not everyone was convinced. William Rulofson, a photographer with whom he had worked earlier in his career, was among those who cried foul. In a letter to the editor of the same Philadelphia Photographer that had praised Muybridge's photographs as "brain turning," Rulofson wrote in August of 1878, "Photographically speaking, it is 'bosh' but then it amuses the 'boys,' and shows ... a fact of 'utmost scientific importance.' Bosh again."

Phillip Prodger

Jacques-Henri Lartigue grew up surrounded by cars. Many of his most dramatic pictures are of cars in motion. The effect of oval wheels leaning forward seen in this photograph was produced by slightly panning the camera to follow the car and releasing the focal-plane shutter as it did so. The result: an image conveying a remarkable sense of speed and motion. —P J

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

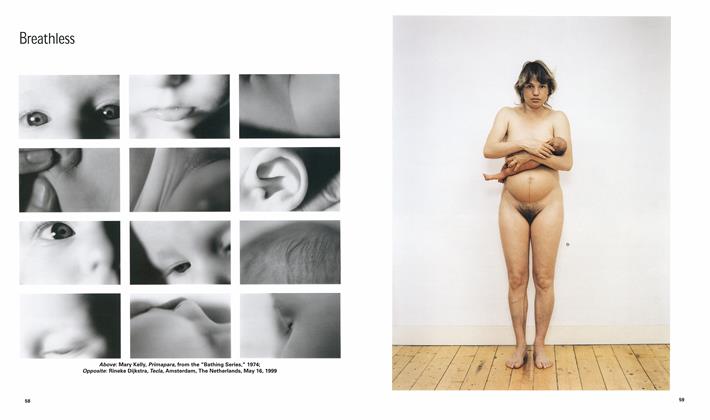

Breathless

Winter 2000 By Martin Barnes, M H-B -

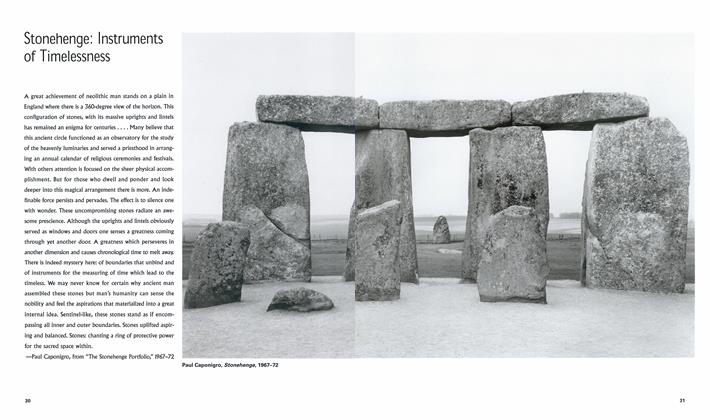

Stonehenge: Instruments Of Timelessness

Winter 2000 By Paul Caponigro -

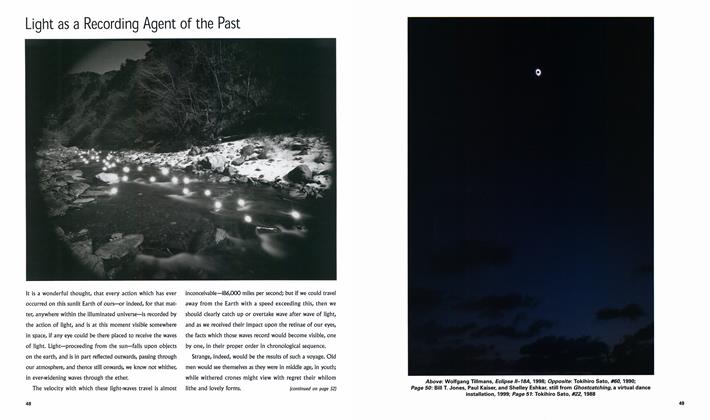

Light As A Recording Agent Of The Past

Winter 2000 By W. Jerome Harrison -

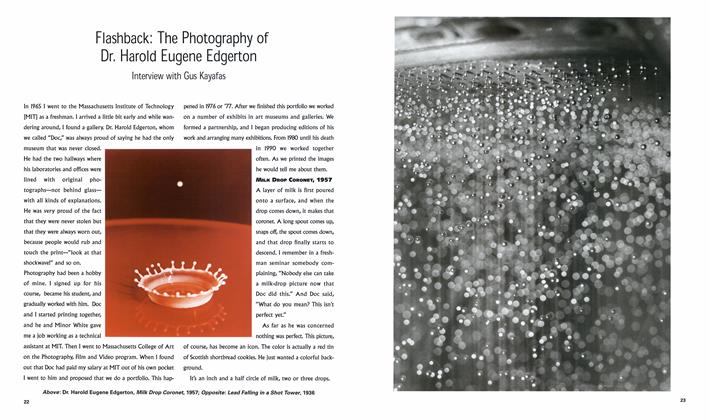

Flashback: The Photography Of Dr. Harold Eugene Edgerton

Winter 2000 By Martin Barnes -

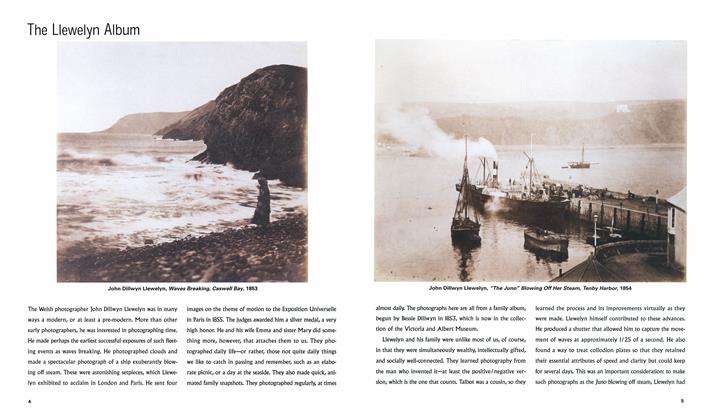

The Llewelyn Album

Winter 2000 By M H-B -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasMariko Mori, Empty Dream Brooklyn Museum Of Art: April 8-August 15, 1999

Winter 2000 By Lesley A. Martin