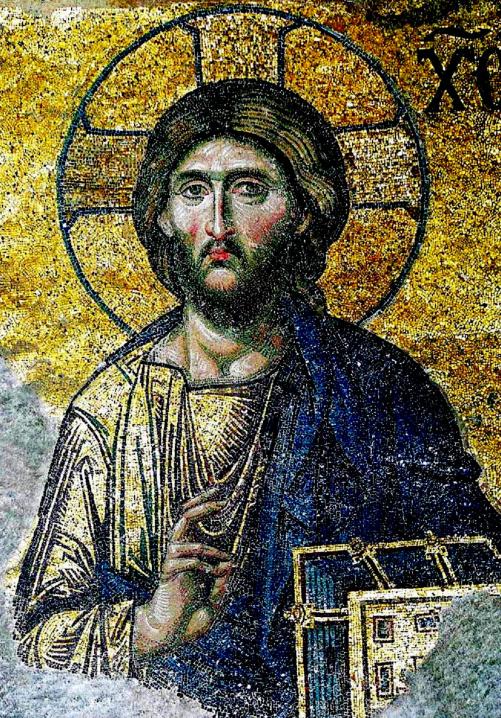

More than architecture, painting was the truly national art of the Byzantine Empire: Byzantine domes and walls were covered with polychrome mosaic decorations or with frescoes and paintings. For religious compositions, painters followed certain “repertoires” provided by monks, who then instructed them the place each character should occupy inside a church. Thus, this Byzantine repertoire was quite fixed because not only the composition of each scene was organized following the Christian liturgy, but also the place a particular painting should occupy inside a church was clearly defined. For example, the apse was occupied by the giant figure of the Pantocrator or Almighty in the act of blessing and with the Scriptures in his hand bearing the Lord’s words: I am the light of the world. This figure was sometimes replaced by that of the Virgin seated on a throne with the Child in her arms. Inside the Church at each side, scenes from the Old Testament were placed in sequence in order to facilitate the teaching of the Holy Book to the congregation.

The wall at the end of the church, inside the facade, was the perfect place for the representation of the Judgment Day and on the side walls of the smaller naves was the procession of the saints of the Greek church, each one of them with their particular features. The Holy Fathers and Priests were represented with the long robes wore by Byzantine priests, while the Apostles still wore the toga of the ancient Greek philosophers: some like Peter, Paul, John, and Andrew were always bearded; on the contrary others like Thomas and Philip were always beardless. In the dome’s pendentives were large multi-winged seraphim, while at the top inside the dome there was a decorated band representing the prophets surrounded an image of the Supreme Maker’s hand emerging from a cloud. This is the classic repertoire of early Byzantine art previous to the iconoclastic controversy. In such initial period the theological element dominated over the pious or devotional. In subsequent periods, Byzantine art gave more importance to episodes related to the Gospel and even the lives of the saints.

Between these two periods -the theological and the devotional- was the iconoclastic period during which it wasn’t allowed at all any type of representation, not even that of the divine persons. The iconoclastic doctrine arose in the eighth century led by the emperor Leo III. His successor, Constantine V Copronymus led it to a extreme when he persecuted and martyred images’ defenders. Iconoclasm was politically supported by Jews and Muslims enlisted in Byzantine armies. The icons were destroyed and the frescoes and mosaics of the churches were blanched. But being a people so used to decorative profusion as the Byzantines were they could not remain indefinitely with their monuments totally devoid of symbols and figures. It was then when Byzantine scholars made use of old artistic themes that could be adopted without scandalizing the iconoclasts. And it was then when these scholars proposed these themes to the artists and even invented new ones. The theme most profusely represented was that of the Throne, called Hetoimasia, an empty imperial chair on which the opened Book of Scriptures was placed. Artists returned to represent sheep going to the Fountain of Life, the Mountain of the Paradise with the four rivers of living water, images of Virtues and Vices, or simply beautiful gardens. But in 787, under Constantine VI, the Second Council of Nicea condemned iconoclasm.

After the iconoclastic controversy, with the pictorial revival followed the repression, artists were eager to restore and reproduce ancient icons. The mosaics were then released from their lime shrouds and the frescoes were restored. But artists no longer painted with the same hieratic and theological style of previous times: now Holy characters were treated with new familiarity. In addition new topics appeared more intimate and personal. As in the previous period before the Byzantine iconoclasm, the main protagonist of Byzantine painting was the Redeemer, the Savior, the Soter. After the iconoclast persecution the favorite figure was the Mother, the Marteroi, the Theotokos. The episodes of the Virgin’s life took a prominent place in Byzantine painting: the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, the Visitation, the Annunciation, all eventually prevailed over scenes of the Passion and Resurrection.

But even within theological guidelines, the Savior’s Mother was imagined more human and earthly. Before the iconoclastic period, Mary was portrayed accompanying the Precursor already in Majesty and interceding for sinners. After the iconoclasts, Mary was represented praying at the foot of the Cross when Jesus was still alive after having accomplished his sacrifice and Redemption. Crucified and dying, He opens his eyes to hear the prayers both of his Mother and his beloved Disciple. It is what is called as Deesis*, or perfect prayer, the ultimate prayer to the God-Man still on Earth and done by his Mother and John the only ones who remained faithful at Calvary.

Simultaneously, the pictorial hagiography* grew with scenes from the legends of saints. The favorite subjects were the saints of the Greek church like: St. Basil, St. John Chrysostom, and the two Gregory, although Eastern and Egyptian martyrs and confessors were also represented but less often. After the iconoclastic persecution anecdotal elements were added to compositions as well as secondary figures and troupes which filled scenes. The figures were elongated and twisted. Thus, the Byzantine religious painting experienced a true renaissance during the 14th century as can be seen in the frescoes decorating the Peribleptos Monastery at Mystras (Greece) or in the temple of Kariye-Camii in Constantinople (now Istanbul ) with its majestic representation of the Descent into Limbo. This version of the anastasis* painted around 1310 in the parecclesion‘s* apse (or funeral chapel annexed to the main church) is a masterpiece of the painting of all time comparable only to Giotto’s frescoes in Padua which were almost contemporary. The mosaics inside of the Kariye Camii and its two narthex were also painted in the early 14th century.

____________________

*Anastasis: From the Greek, meaning resurrection. The term refers most commonly to the Resurrection of Jesus.

*Deesis: In Byzantine art, and later Eastern Orthodox art generally, the Deësis or Deisis (Greek for “prayer” or “supplication”), is a traditional iconic representation of Christ in Majesty or Christ Pantocrator: enthroned, carrying a book, and flanked by the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist, and sometimes other saints and angels. Mary and John, and any other figures, are shown facing towards Christ with their hands raised in supplication on behalf of humanity.

*Hagiography: A hagiography is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader. The term hagiography may be used to refer to the biography of a saint or highly developed spiritual being in any of the world’s spiritual traditions.

* Parecclesion: From the Greek meaning “chapel”. A type of side chapel found in Byzantine architecture.

6 thoughts on “Second Golden Age of Byzantine Art (Painting before and after the Byzantine iconoclasm)”