Russia was the last conquest of the Byzantine art. The initiation of the Russian people in the art and religion of Byzantium began before 1000, when the Prince of Kiev Vladimir “the Saint” became Christian in 989. To get rid of the Russian threat, the Byzantine emperors Basil and Constantine gave Vladimir their sister Anna in marriage, in turn Vladimir had to convert to Christianity in order to be formally linked to the imperial family. For this reason the Russian Church is still Orthodox, and even their customs, alphabet and art have a strong Byzantine influence. After he converted, Vladimir moved to the capital (in Kiev) where he built the first church, the mother of all Russian churches, the St. Sophia’s Cathedral in Kiev built mostly by Byzantine-Greek artists coming from Byzantium and finished in 1307. It is a temple with five naves with apses covered by domes and decorated with mosaics in pure Byzantine style. From Kiev the Byzantine art spread throughout Russia.

In the 15th century the Russian court moved north of Kiev to Moscow fearing the Mongol invasions and since then this city became the political and cultural center of Russia. Around 1473 Ivan III married Sophia, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, which allowed him to be considered as heir to the emperors of Byzantium. Taking as his own insignia the imperial double-headed eagle, he turned Moscow into a third Rome. One of Ivan III successors, Ivan IV the Terrible, took the title of Tsar, i.e. Caesar.

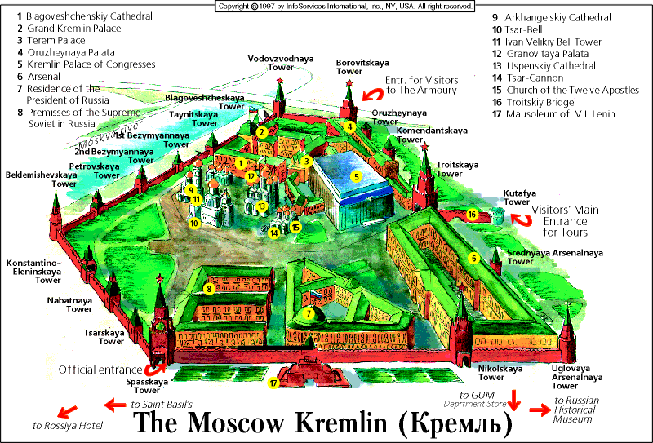

Under Ivan III, between 1475 and 1479, the Italian architect Aristotle Fioravanti built, inspired in former Russian models, the Moscow Cathedral of the Dormition (dedicated to the coronation of the tsars), which like that of the Annunciation (dedicated to their baptism) tended to turn away from a purely Byzantine style to adopt a new structure with the use of the onion domes* so typical of Russian art, although inside with their luxurious painted decoration still followed typical Byzantine styles. The same Russian style is found in the cathedral dedicated to the Archangel Michael, which served as royal pantheon built in 1505 by other Italian: Alevisio Novi from Milan which was inspired by some Venetian palaces whit its facade having two galleries of overlapping columns. These three cathedrals, plus some palaces, towers, and barracks, are surrounded by a wall built by the same Alevisio Novi. These constructions constitute the famous Moscow Kreml or Kremlin meaning “fortress inside a city”.

During the 16th century, the style of Russian religious architecture is characterized by the adoption of a “pyramidal” structure with a large polygonal bell tower in a pyramidal form sometimes surrounded by other towers crowned by large onion domes: such is the solid form of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow a building erected by the architects Barma and Postnik between 1555-1560 and that encompasses nine churches. St. Basil’s Cathedral is shaped as a flame of a bonfire rising into the sky and its eight separate domes, covered by an orgy of colors and dominated by the central pyramid, have an absolutely fantastic look and seem to be the dream of a mad architect. This Russian national style adopted drastic changes from the 17th century under the influence of the western Baroque.

However, the Byzantine inflow never stopped throughout the history of Russia. Russian monks and bishops used to complete their studies in Constantinople, while the frequent contact with the Greek church was promoted by the widespread custom to make pilgrimages to the Holy Land. All these facts explain why over any other kind of Renaissance, Germanic, and French influences, Russian art has always retained a Byzantine seal until the 18th century. It is an art that never felt predilection for sculpture: music and painting were the most cultivated arts, as they had been among the Byzantines.

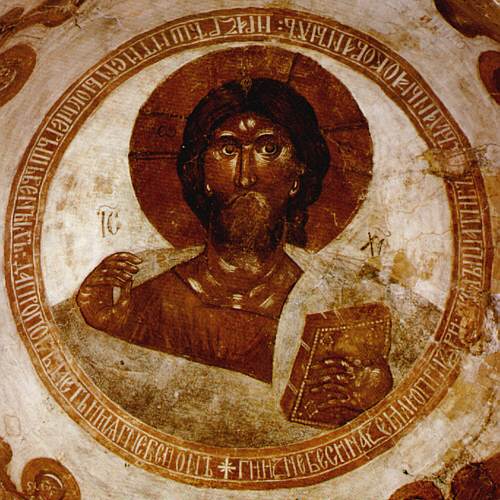

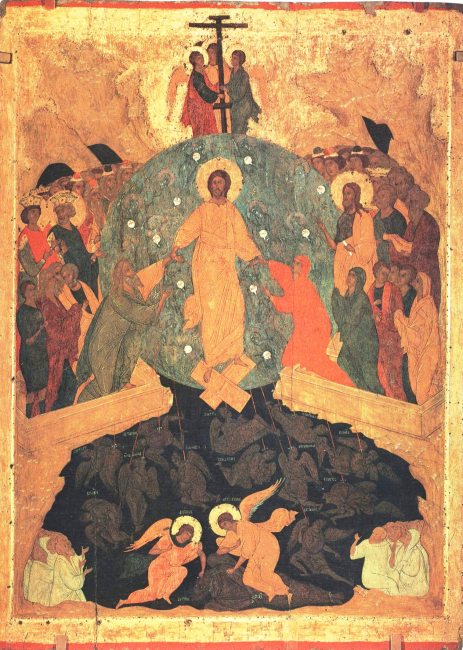

In Russia, religious painting began to acquire personality during the 11th century thanks to the influence of Greek artists coming from Byzantium to Russia, like Maximus who in 1378 painted frescoes and icons for the Church of the Transfiguration of Novgorod, or like Theophanes who worked in Novgorod and Moscow by the same time as Maximus. The splendor that in the Russian church acquired the iconostasis, or wall of icons and religious paintings that separates the nave from the sanctuary in a church, contributed much to the new pictorial revival in Russian art. Soon local schools of painting appeared such as the school of Pskov from the 13th century, whose center was the monastery of Mirojvski, and the school of Novgorod. The Moscow School gained importance from the early 15th century with the figure of Andrei Rublev, perhaps a disciple of Theophanes, a painter noted for his preference towards symbolic concepts and the tender elegance of his compositions. His masterpiece is the famous icon of the Trinity represented in an oriental manner by three equal but different angels. The rotating pace that these three bodies produce and the use of color harmonizing blues and pale yellows are the probable causes of the indefinable charm of this masterpiece. Another master painter, Dionisius painted in the early 16th century some scenes from the life of the Virgin in the church of Ferapontov near Kirilov. The decline of icon painting began during the 17th century, when narrative themes were treated with more realism while exaggerating the pictorial ability.

The diffusion of the Byzantine styles in Western Europe was accomplished mainly by the trade of small objects of easy export at the time. Masterpieces of Byzantine art only arrived in Western Europe thanks to war booties brought by crusaders after the sack of Constantinople in 1204 and from other devastated provinces of Asia. One of these masterpieces of Byzantine art that came to Western Europe is the icon called “The Three twins”. Another two beautiful Byzantine icons also appeared in the inner sanctum treasure of the church of St. John Lateran.

Also, the silk fabrics that were commonly exported in those times contributed widely to the diffusion of Byzantine art. During their trips, Crusaders brought famous textiles used to wrap the saint’s bodies and relics. In Byzantium, the emperor kept a textile factory in a former baths or thermae which was restored solely for this purpose. This place was called the Zeuxippus and stood by the Augustan. Some of the themes represented in these silk fabrics were obviously Sassanid Persian. These Parthian and Sassanid motifs were represented within ornamental circles, that is why they were called pallia rotata. In ancient inventories these silks were given particular names, like “the fabric of the Elephant wheel”, “the fabric of the griffin wheel”, “the fabric of the lion wheel“, etc. Sometimes these silks reproduced Gospel scenes within these ornamental circles.

________________________

* Onion Dome: Refers to a dome whose shape resembles the form of an onion. These domes, predominant in Russian architecture, often have larger diameters than the drum upon which they rest. Some theories state that onion domes were a strictly utilitarian feature because they prevented snow from piling on the roof of the church. In Russian architecture, onion domes often appear in groups of three representing the Holy Trinity, or five representing Jesus Christ and the Four Evangelists, when domes stand alone they represent Jesus.

* Onion Dome: Refers to a dome whose shape resembles the form of an onion. These domes, predominant in Russian architecture, often have larger diameters than the drum upon which they rest. Some theories state that onion domes were a strictly utilitarian feature because they prevented snow from piling on the roof of the church. In Russian architecture, onion domes often appear in groups of three representing the Holy Trinity, or five representing Jesus Christ and the Four Evangelists, when domes stand alone they represent Jesus.

One thought on “Byzantine Art in Russia”