The low-end: The Amiga 500

The Commodore CEO wasn't the first one to make the case for a cheaper Amiga. Hardware engineer George Robbins felt that a lower-end Amiga was a better idea right from the start, and Bob Russell said he had been fighting for such a product before the Amiga 1000 was even released. Still, it took someone higher up in the management chain to make the new machine—dubbed the Amiga 500—a reality. Rattigan had to choose between the remnants of the original Los Gatos crew who had designed the Amiga 1000 and Commodore's core group of engineers in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He chose the latter group because he felt they would be "more bloodthirsty" and thus likely to deliver the machine faster.

He assigned Jeff Porter, the engineer who had developed the innovative (but canceled by Rattigan's predecessor) LCD computer, to be the director of new product development. The lead engineers for the 500 were George Robbins and Bob Welland, who had previously worked on the also-canceled Commodore 900 Unix workstation. They were an odd bunch to be tasked with coming up with the computer that had to save the company, but in many respects they echoed the rogue team of misfits that had come up with the Amiga in the first place. George Robbins, a gentle and kind man with long hair and a walrus mustache, practically lived at work and often forgot to do his laundry. His coworkers, who loved Robbins, but worried about his personal hygiene, would constantly buy him new shirts to wear and quietly dispose of the old ones.

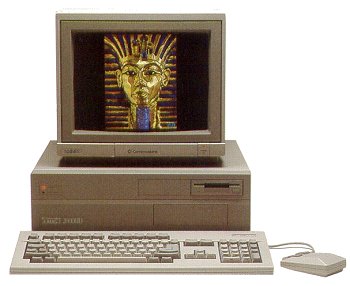

The Amiga 500

Robbins needed to avoid the distraction of laundry duties, as he was intensely focused on cutting costs on the Amiga. Welland was the ideas man, while Robbins was the practical engineer who could take great ideas and turn them into working electronics. One of the ideas Welland had was to increase the RAM on the "Agnes" custom chip to 1MB so that the Amiga could support higher graphics resolutions. The original Los Gatos team was a bit miffed at the proposed changes to their design, which they felt were not revolutionary enough, and made it known that they didn't think the changes would work. This motivated the Amiga 500 team even harder.

"Fat Agnes" did end up working, and the original Amiga engineers admitted that the design was probably a good idea. The modest change increased the Amiga's capabilities while also keeping a high level of backwards compatibility with existing software. "It was a step in the right direction, but it violated the [original] idea of the bus architecture and actually slowed the machine down," RJ Mical said later.

Meanwhile, the pragmatic Robbins was finding ways to redesign the Amiga's motherboard to reduce costs. He took out the ability to connect directly to a television set and replaced it with a separate adapter, the A520. This turned out to be a good idea because most users weren't using a TV set anyway—the fuzzy image quality of TV sets caused text to "bleed" and made it hard to read. He took the power supply out of the main machine and integrated the keyboard into the case, which was inspired by the design of the Commodore 128. The 3.5 inch floppy drive was fitted in on the right-hand side of the machine. An thin expansion slot was placed on the other side. Devices could be plugged into this slot directly without removing the Amiga's case.

The high-end: The Amiga 2000

While the 500 project continued, Commodore needed people to work on the high-end Amiga 2000 design. Unfortunately, Rattigan's massive personnel cuts had left few engineers available for the project. The task was farmed off to Commodore's German subsidiary, but the engineers there simply took the original Amiga 1000 design, added a hardware interface for adding expansion cards, and put the whole thing in a standard PC desktop case. This wasn't quite what Rattigan was looking for.

The task of redesigning the Amiga 2000 fell on one Dave Haynie, whose broad shoulders and ever-broadening ego were large enough to carry this burden. "I was the design team for the A2000," Haynie said. "That's kind of the way things were there because we had a lot of layoffs. I was working day and night and there still wasn't enough time to do everything." Haynie would work through the week, then let off steam on Friday by retiring to Margaritas, a local dive where the beer was cheap and plentiful.

Haynie was inspired by the designs made by the Los Gatos team and determined to improve on their elegant architecture. He designed a new custom chip, called Buster, to handle the expansion bus. The bus design, which was called "Zorro" in reference to one of the original Amiga prototypes, was also ahead of its time. Unlike the ISA slots in the IBM PC, the Zorro slots had "autoconfig" built-in and would allow expansion cards to be work instantly without any manual configuration of jumpers or resolving device conflicts.

Built like a tank: the Amiga 2000

Haynie wanted to design a machine that would be easy—for both end users and Commodore itself—to upgrade to more powerful processors that were coming out of Motorola's design labs. He put the CPU on a separate board that could be swapped out later. From the German designers he got the idea of a genlock—a way to directly output computer images on top of video with no loss of image stability. He turned this idea into a separate dedicated video slot, which could be fitted with a genlock card or other types of video processing cards. This idea would later turn the Amiga—already a multimedia powerhouse—into the standard computer for the video industry.

The Amiga 2000 would have unprecedented expandability, with five open Amiga Zorro expansion slots, four IBM PC ISA slots, and the aforementioned CPU and video slots. This was to be a serious machine, for serious users. The case was recycled from the canceled Commodore 900 workstation project.

Not everybody liked the idea of the 2000. Amiga creator Jay Miner, when asked about the machine at an Amiga user group meeting, recommended that Amiga 1000 owners hang on to their existing computer instead of upgrading. Jay's feelings weren't all about sour grapes. He felt that the computer had not been improved enough, given the advances in technology that had occurred since he first started designing the original Amiga back in 1982.

reader comments

4