Art In Conversation

NJIDEKA AKUNYILI CROSBY with Jason Rosenfeld

“You don’t have to give up your culture. You just carry the stories that you brought with you and exist next to other people, and it actually makes for a richer world.”

Ms. Akunyili Crosby was born in Enugu, Nigeria, in 1983, moved to Lagos for boarding school when she was about 10 and lived there until she was 16. She then moved to the US and after taking some courses at the Community College of Philadelphia completed a BA with honors in Biology and Art at Swarthmore College. She earned a post-baccalaureate certificate at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia (PAFA) in 2006, and an MFA from Yale University in 2011. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband, the artist Justin Crosby, and their two children.

The following is a condensed and edited version from our New Social Environment daily lunchtime conversation #63 (June 11, 2020), and a follow-up conversation on June 26.1

Jason Rosenfeld (Rail): Can you talk about your connection with art in Nigeria before you came to the United States?

Njideka Akunyili Crosby: Growing up I did a lot of drawing. I’d find a piece of charcoal from outside and I’d make copies of photographs I saw in magazines. My dad bought Time magazine and Newsweek religiously and I would do drawings from them. So that was the extent of what I did regarding art. We lived in Enugu, which is just about an hour from Nsukka, which has a very rich history of Nigerian art. It’s where the Nsukka School was based, El Anatsui lives there—and I’m ashamed to say my family had no connection to it, that I didn’t even know it existed until years after I left. My family was very disconnected from it because we’re a very science-heavy family.

Rail: Your mother taught at university?

Akunyili Crosby: Yes, she was a faculty member in the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, and my dad worked at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital in Enugu, Nigeria. So then when I went to Lagos, to Queen’s College, I started taking drawing classes. I remember the school going for excursions to art museums. There were a few small collectors who opened up their houses like the Didi [Museum] that we had gone to. That’s when I really knew that this was something I was interested in—but my first oil painting class was at the Community College of Philadelphia when I moved to the United States. My mother wanted us to come to the United States because the education system in Nigeria is very similar to the education system in the United Kingdom, which makes you pretty much choose your path in life when you’re about 13 or 14 years old. So she applied for the Green Card Lottery—which, of course, we’ve heard [exasperated sigh] the person who lives in the White House right now say very disparaging things about it, and how “they are sending over the worst they have to give.” It’s absolutely not true. People self-select to apply. So my mother applied for the Green Card Lottery and she got it, and if you get it then all your children get it, so we all got the legal right to live in the United States. We moved to Philadelphia because the eldest in the family, my sister, was going to Penn.

At the Community College of Philadelphia I had taken a painting class with an incredible artist called Jeff Reed. He had told me that his best friend was the head of the art department at Swarthmore. So I went to visit and I knocked on his friend’s door, Randall Exon, and he was at his office, and I went inside and we ended up talking for over an hour. I honestly can say I ended up going to Swarthmore because of him. Because I like environments that nurture their students, that show they care for their students, and I got that feeling when I visited that if I’m just a prospective student and he could spend so much time with me, imagine if I came here. So I ended up going, and Randall Exon ended up being my mentor. He was actually integral in my decision to become an artist.

Rail: Exon is a really interesting artist. It’s a kind of post-Eakins, post-Wyeth, George Stubbsian realism which is also surreal at the same time. My mentor Robert Rosenblum would have loved it. It has nothing visually—that I can tell—that relates to what you do. But as the teacher you don’t just want to make people do what you do.

Akunyili Crosby: Exactly.

Rail: And I’m sure that’s something that you brought into your own teaching practice. I wanted to also talk a little bit about ideas of biology—you finished your biology degree, so I expect you had some actual innate interest in it. But is there anything about it that you might talk about with respect to your work?

Akunyili Crosby: Yeah I keep thinking if I were a doctor, I wouldn’t have been unhappy at all. I think I would’ve been very good at it! [Laughs] Not to toot my own horn, I was a good student. I have very steady hands. I was going to be a surgeon. I was going to do reconstructive facial surgery, and I was determined to be the best in the world. [Laughs] But I am a researcher. For instance, I tell my husband, “I feel like Sherlock!” [Laughs] because I have a few images and I’m figuring things out from the pictures and zooming in, so I do research very well. And that is just like training in the sciences. And the other thing is, when I was at Swarthmore I was actually very curious about how I could be interested in biology and art. They seem so disparate and random. I remember taking an embryology class with this amazing professor, Scott Gilbert, and at an office visit he was actually telling me that it’s not as uncommon as people think. And since he said that I started paying attention. A lot of artists were bio undergrad or were about to go to med school. I run into more and more all the time. So it’s not as odd a combination as people think. A lot of scientists were actually very good artists and it was their art background that actually made them very good biologists or scientists because being an artist is about learning to organize things and see patterns and how things fit into each other. It’s that kind of thinking that made Darwin notice the changes in the finches when he was in the Galapagos. And also the fact that they were drawing these things and in drawing they were having to observe more. It just made me feel like I wasn’t odd and I wasn’t alone.

Rail: There’s lots of commonality there. I think of someone like John Ruskin in the 19th century who was essentially a scientist when he was young. He published in geology journals and he trained himself to look very carefully and precisely and that idea of doing research, understanding the elements of a thing and then translating it, whether in a drawing or painting or some other form. So then you went to Yale.

Akunyili Crosby: [Laughs]

Rail: What was Yale like to be a student there in that period? The late 2000s.

Akunyili Crosby: The big exhale.

Rail: [Laughs]

Akunyili Crosby: It’s always tough for me to talk about Yale because it’s a mixed bag in that my experience there was invaluable to my work. I learned so much, my work grew so much, it changed so much, and I got to work with some phenomenal people. So much of the work I do now is really underpinned by printmaking—you can see all the stencil tipping and stuff going on in the back—and that really started with this incredible class I took with Rochelle Feinstein when I was there. There’s a phenomenal painter, Catherine Murphy—I got to work with her. She was a joy. Once again, I love learning environments that are loving and nurturing. She was those things.

Rail: I actually reviewed her last show at Peter Freeman. She’s fantastic.2

Akunyili Crosby: Incredible. Nicole Awai was amazing. And also, going to a program like Yale where you have access to classes outside the School of Art—I got to, for instance, study with Hazel Carby. I took an African and Caribbean diaspora literature class, which was a game changer for my practice and my work, and the way I was able to talk about and think about what I was trying to do. So there was all of that incredible stuff that I will always be grateful for, but there was also a lot of other stuff. I didn’t feel as nurtured as I was used to or as I would have liked to be. But, at the end of my first year—looking back now—that probably was one of the most depressing years of my life. And I think what really made it clear was that after Yale I went straight to do a residency at the Studio Museum, and being at the Studio Museum and just having this feeling of, “This. This is what it feels like to feel supported and loved by an institution.” So, Yale was really tough. And I kept thinking about the sociologist, Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom, who talked about how every year there are always Black students—especially Black women, Black graduate students—crying in her office. And she said the advice that she gives them, and she wishes to send this out to everyone, is sometimes these institutions do not know how to love us. And you always just have to take what you can out of it, and leave as quickly as you can with your sanity intact.

It was just really tough to be in a place that made me question myself, that made me wonder. Hazel Carby’s class was so important, because that was the first time I felt I wasn’t alone, and what I was trying to do was valid, what I was trying to say was important, making work that affirmed my existence mattered. I got a letter my first semester that I was on academic warning—that they did not know what I was doing—and the second semester I was put on academic probation—because I wasn’t working—which was ridiculous. Of course this was years before I even knew the term “racial microaggression”—microaggression is the wrong term to use because there’s nothing micro about it when you’re in the middle of it. It’s very soul crushing. Anyway, I don’t want to go back to an angry sad place, but it was a very mixed bag. I don’t think this is something that is unique to Yale. Because what has been most shocking to me when I go to schools and talk to other students, which is why what Dr. Cottom said resonated so much with me, is to see how many other people of color have these kinds of experiences in graduate programs. Not just even in art, in various creative fields. Jeremy O. Harris just did a tweet-thread this week about how horrible his time at the Yale School of Drama was, and his clashes and not feeling supported. So it’s everywhere. I remember being at Skidmore and talking to two Black women who came to see the show, and they were talking about their grad school experience and it was like a mirror of mine. 3 They were talking about this experience they had in this one class, where you say something and your teacher ignores you, and then someone else says the same thing—someone who is probably a white man—and the teacher affirms what they say, like, “Oh yeah, that’s good,” and you continue the discussion. And it happens often enough that you actually just end up shutting up in class. You know, when you just have that lightbulb, like “Oh my god, that happened to me!” And at the end of class, you just go in and you sit down and you say nothing because, in your mind, you just think, “Well, this teacher is acting like I have nothing to say. And if everything I have to say is garbage, I’ll just sit down.” The point I’m making is that it’s not just Yale. I think that’s why a lot of institutions have been putting affirmative statements out about how they support the movements happening right now, and Black Lives Matter—and I love that people are calling them out. Because you really have to examine your institution and the way you act towards students of color you bring in. If you’re going to say that truth, that Black lives matter, if you’re going to make that affirmation, you actually have to be a place that proves it. And it’s not just about Black people but also people of color, LGBTQ, nonbinary people, trans people, people with disabilities. This is why people push for diversity in faculty. It’s also time for certain people to go. If you cannot broaden your worldview, you should not be teaching in certain institutions.

Rail: It’s something that every university, college, and institution needs to be thinking about all the time, and faculty that don’t have empathy, I don’t understand it. And faculty who are not inclusive. So I expect that you are a great teacher—you have been teaching at California Institute of the Arts and UCLA. Can you talk a little bit about the way that you’ve translated your experiences into teaching over the last few years?

Akunyili Crosby: I love to teach because I think teaching is also a learning experience. You mentioned earlier on that it’s good when a teacher doesn’t make you work like them and I think that’s very important. Some of the best teachers I’ve had are people who make the best in you blossom—as opposed to forcing their way of working on you. It’s rare. The times I have it’s been so meaningful that it made me want to teach. So I love teaching. It’s hard for me to get time to teach because my work is very slow and time-intensive, and now I have two kids—one that is one year old—so I try to find ways to make sure I teach.

Rail: Thank you so much for sharing all that. It’s really important for people to hear about these experiences and everything that makes you who you are. I wanted to start our discussion of your work with Mama, Mummy and Mamma (Predecessors #2) of 2014. It’s part of a series that you call “Predecessors,” which are about your family as is so much of your work. I wanted to talk about it in the context of its role, subsequently, as a design that you’ve used in public art installations.

Akunyili Crosby: I had gone to Nigeria in December 2012, and I went back to my grandmother’s house. My dad grew up in the village with his mother, and then he ended up moving to the town Enugu. I was born in Enugu but I used to spend some summers and weekends in the village with my grandmother.

Rail: When you say village, can you clarify this for me?

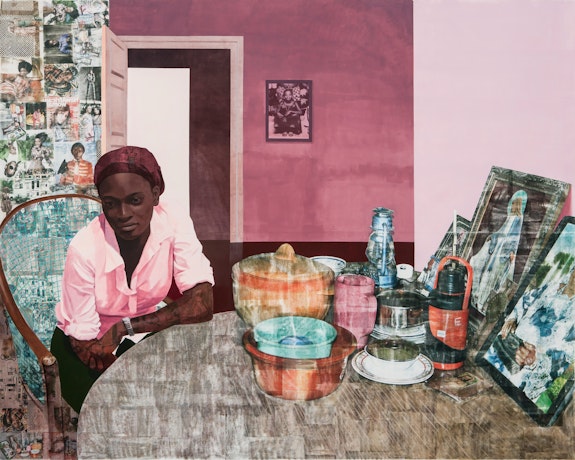

Akunyili Crosby: Oh yeah, I realize people are thinking of huts. [laughs] Enugu is a town. The village is where your paternal lineage came from. Everybody lived in this one place, but then starting from the generation before my dad they started leaving. The world grows, people move. So from spending multiple generations living in one area, people start moving to towns and cities for school, for work, and whatnot. But what people do, especially people from my tribe, is that they maintain a connection to that place where their family is from, and they go back there for Christmas, Easter, or any other big holiday. So that’s the village, about a one hour drive from Enugu. I never grew up in the village—I used to spend summers there, and weekends, but that wasn’t where I grew up. I grew up in Enugu. Then I moved to Lagos—so I feel there are parts of my person, who I am, parts that were formed in Enugu, parts that were formed through this experience of going to the village, and living in America, and being an American citizen now. And in the works I’m trying to navigate all of those. Mama is what we call my grandmother, and Mummy is my mom and her picture is the black-and-white one in the background, and Mamma is what we call my little sister who is in the pink shirt. A lot of my work talks about generations: my grandparents’ generation, my parents’ generation, my generation, and the shifts that have happened in those—cultural, psychological—in Nigeria.

Rail: How did you come to acrylic paints as your choice?

Akunyili Crosby: After I left PAFA, I was doing stretched linen with rabbit skin glue and lead ground—the whole back to the way it was done hundreds of years ago kind of painting—I was using oil. I applied to graduate school when I felt my work had—not stagnated—but almost reached the furthest I could go by myself, and I needed help to help me see how I could push it forward. I was at a point where I kind of had an idea of where I wanted to go in terms of content—I knew what I wanted to talk about—but I didn’t know how to do it. The painting I was doing wasn’t jiving with what I wanted it to say. So when I got to grad school, my first semester I realized I had to pretty much stop what I was doing and start from scratch. I was doing a lot of experiments. I was drawing a lot. I was still painting. I was doing watercolor washes. And what I realized was that if I wanted to work through ideas quickly, I couldn’t spend a semester working on one painting. And so I realized that the way to work quickly with ideas was to use something that dried fast, because I was interested in layering and building, and so acrylic seemed like a good idea. For a long time, I was doing ink washes, stencils, overlay cutouts, but I was very hesitant on acrylic because I felt like everyone I loved at that point was using oil. I was very into Caravaggio and Zurbarán and Vuillard, and I just thought, “Oh, but you can’t make acrylic luminous, I don’t know how to do it.” And every time I tried it, things looked flat. And then one day, I walked into the Yale University Art Gallery and they had a Kerry James Marshall on display [Untitled, 2009], and—I don’t know if people listening have had this experience of that one artwork that you remember the day you saw it, and it’s like your life as an artist has not been the same since. Standing in front of it, my mouth was open, not for like a second but a very long time. Every time I think about that experience I get goosebumps. First of all, there was the phenomenal impact—because it was right at the end when you walked in the main walkway. So there was just the power of seeing that incredible Black woman with the palette and she was an artist and big hair and she’s looking at you like, “Yes, this is my space.” You do not see that a lot! [Laughs]

Rail: Right. That very direct gaze that she has, that amazing locked-in gaze.

Akunyili Crosby: She just claimed her relationship to that museum space in a way that, historically, hasn’t happened a lot. And then to see that this luminous, beautiful, incredibly made work was done with acrylic. What that made me realize was that it was possible to make phenomenal luminous paintings with acrylic, and then the challenge I had for myself was to try and figure out how to do it. And so I started experimenting—and I still do, I make lots of little tabs and samples, and play around with the things I mix into it. Like, what happens if you paint by layering four different layers?

Rail: Marshall works on PVC panel—you are using paper though, you’re working on a very different kind of support. Is that because it aids in the transfer process that you developed?

Akunyili Crosby: Yes. You can transfer on canvas, but it’s not the look I’m interested in. I want a very specific abraded quality that I get best on, not just paper, but on a very specific type of printmaking paper.

Rail: I’m thinking about what Rauschenberg used to do on canvas with silkscreening. You didn’t want to do silkscreening, it makes it too clean, it’s too precise. So this is something which works really well.

Akunyili Crosby: Exactly. It’s Rives BFK paper. I buy it in 42-inch-wide rolls and I seam them together. Another question I had for myself is, “Why am I painting on canvas?” I wanted everything I did to be a very conscious decision. Painting on paper is just a slightly rebellious part of me—like I’m bucking this way of painting I used to do before—but it also suspends my work in this space where it is drawing. And it is important to me that it lives in this space between painting and drawing and printmaking, because the content of the work is about existing in different spaces and how you kind of aren’t just one but this new being that has aspects of those different spaces but isn’t tied to anyone. So thinking of me as the girl who grew up, spent time in the village, and the town girl, and the Lagos girl a little bit, I am also American, and who I am is a mix of all those things. All those things have come together to yield a new thing—a new trans-culture.

Rail: Can you briefly describe what you’re doing with the transfer process?

Akunyili Crosby: The transfers are not collage. Transfer is a printmaking technique where you print out a picture and you put it face down on my Rives BFK paper, and using a solvent, in my case acetone, I transfer just a very thin layer of ink from the printed paper onto the paper. So I have an image-bank that I’ve been putting together since I finished at Swarthmore. I went back to Nigeria, for a year and the Nigeria I went back to in 2004–05 was very different from the one I left in 1999. There was just this renaissance happening in the country, Nollywood had already exploded, Nigerian music was taking over the continent and to some extent the globe, Nigerian fashion. So I was seeing all this stuff happening and I felt that there was this new generation of Nigerians—Chinua Achebe talks about how Africans had to tell their own stories, and I think he said something along the lines of the story will always glorify the hunter, if it is the hunter writing it and never the lion.4 So I was seeing this cultural explosion happening and it was very fascinating. I started collecting a lot of pictures of the fashion designers I was going to visit, the magazines I was seeing around Nigeria at the same time. That’s how the image bank started. What I’m doing is taking images from my photo bank and using the acetone transfers to grid them, to kind of put them in certain designated areas in the work. They’re usually to add cultural, historical content to the work.

Rail: And all these things, like these album covers and magazine covers and images, you can change the scale, the size of them as you see fit, but they’ll all come out reversed?

Akunyili Crosby: They will all come out reversed, but if I want them to come out the right way then I’ll just reverse it before printing. So sometimes with the text I still leave it reversed. It’s intentional because if you want to read it you can read it. At 10 o’clock from my sister’s head [in Mama, Mummy and Mamma (Predecessors #2)], there’s a red image. That’s Genevieve [Nnaji], the Nigerian actress, and it says “New African Woman.” So if it’s the right way up it announces itself too much, and you zoom in on it and latch onto it in a way that kind of takes attention away from everything else and makes it a little more than I want it to be. But if there are certain things that I find really important—in some of the works that have images from Black Lives Matter protests from Ferguson—I will flip those if I transfer it, because I want those read clearly.

Rail: How do you use the computer when you’re making these kinds of large scale works?

Akunyili Crosby: I am not very good with the computer and I like to do things by hand. But when I was in graduate school, Peter Halley came for a studio visit once, and I was working on a big piece, and I had this area at the top that I had painted yellow and it didn’t work and then I painted it blue and it didn’t work, and so he said, “Well, instead of spending so much time trying to repaint this big area, why don’t you do little studies on Photoshop?” And I thought, “Oh no, I hate technology.” But eventually I gave in and started using Photoshop, and it has become a major tool for me. Usually, the compositions I still do by hand. I use Photoshop for a lot of determining color choices. For composition, I do lots of little sketches as I try to figure out what works. So what I try to do is I make a pencil drawing, I take a picture of it, I print out the pencil drawing, and then I do drawings over that to figure out the composition. I will also put a big piece of glassine over something I’m working on, and then try to figure out the composition, and once I’m happy with what I have, I trace it out with carbon paper. And the reason why I do that is because the transfer has to go on raw paper. I kind of have to have a slightly clear idea of where it’s going and I have to keep that area clean. So this is very akin to printmaking, it requires so much pre-planning.

Rail: And that is also what makes it so time consuming, because mistakes are very difficult to rectify.

Akunyili Crosby: Exactly. It can be fixed, but I always say there’s nothing that can’t be fixed, it can just take a few days to do so.

Rail: You display these with just clips on a wall, not glazed, and not in boxes, not framed.

Akunyili Crosby: That is my ideal way of displaying it—there’s a finished work here [in the studio] but you can’t really see the surface. It’s covered in plastic just in case I accidentally splash paint on the floor. [Laughter]

Rail: Or the kids come into the studio and make a mess.

Akunyili Crosby: Which happened!

Rail: Of course.

Akunyili Crosby: One of my kids came the other day and I set them down there and they did some painting and then of course I realized this is not working! They cannot be here when I work. [Laughs] I like displaying it on its own with just clips, because I put in a lot of work on the surface. These are surfaces that are made for you to really be [gestures to indicate close proximity] this far away from. Nothing gives me joy like when you’re in your own show and you’re watching people look at your own work. I love it when people come really close to the work. I think of surface as a way of moving people through this very large space. So I already mentioned mixing things into the paint. I mix up crushed steel. I had a friend in Baltimore who was working with marble and I got a bunch of marble dust from him, and I’ll mix that into the work. I’ll mix glass beads. I’ll use a lot of rollers to do very thin layers and just put multiple layers on—so sometimes you’ll see something that looks like a tan, but when you come close to it it’s four different colors layered together, and everything shimmers through. I want people to have the experience when they’re far away, and you kind of enjoy the image, and then you come up close and enjoy the surface of it. A lot of that is not lost but reduced, when it’s behind glass.

Rail: So let’s talk a little bit about how this then translates to the public works and your installation at the very southern end of the High Line in Manhattan, right next to the Whitney Museum of Art, a version of Mama, Mummy and Mamma (Predecessors #2) of 2014 but here as a digital print on vinyl.5

Akunyili Crosby: Jane [Panetta] from the Whitney Museum reached out to me and they invited me to do this billboard project, and I sat on it for a little while. I wasn’t quite sure. On one hand, I was thinking “Oh, I put so much work into surface, my surface is important, these are meant to be seen in real life.” I mean at that point I didn’t even like having my work disseminated online and on computer screen. I felt like it just reduced it in a way. Now I’m very fortunate my work has been shown widely, given how few works there are, and some people have gotten the chance to see it in real life, but I remember when I was at the Studio Museum when I was just beginning, I had so many visits where people would come in and say, “Oh, this did not look how I expected from seeing it online,” and I thought, yeah, you know, it doesn’t translate. So I felt like I didn’t want to do this because of that, but then on the other hand, I felt it’s so important to have this work there and of course I keep thinking of one of the driving things for me—I think of it a lot, I talk about it when I do artist lectures—is George Gerbner, who was a cultural theorist. He actually founded the Cultural Environment Movement, which was an advocacy group promoting greater diversity in communication media. So he said, “Representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation.” And I thought, can you imagine what it means to have up next to the Whitney at the end of the High Line where thousands of people will see this while it’s up, an image like this? So that has really been the path that has made me drop my reluctance to do public commissions and now I actually really love them.

Rail: It’s amazing how you see it here because many of your works, the perspectival system is off to the side or askew, but here it lines up perfectly with the orthogonals of the street in the kind of immediate, sort of head-on recession of the room. It has a kind of illusionism, which is quite wonderful there.

Akunyili Crosby: Thanks. This actually ended up being its own work called Before Now After. It was expanded [at the left] because of the aspect-ratio of the space. I didn’t want to have empty white bands at the end, and I didn’t want to cut into the image to make it fit, so I expanded it and I was very happy with it.

Rail: What happened to it when it moved across the country to LA in the installation Obodo (Country/City/Town/Ancestral Village) from two years ago on Grand Avenue on the exterior of MOCA?6

Akunyili Crosby: So “Obodo” is an Igbo word that really means all those things. It means your ancestral village, so my Obodo is where I used to go to visit my grandmother, Obodo is a town, it’s a city, it’s a county. So I was really thinking of how that word speaks to what I’ve been talking about, inhabiting different spaces. I got this invitation from MOCA. I think it was right around Thanksgiving in 2017, and they wanted it up in like a month [Laughs]. The turnaround was very tight, so I knew I couldn’t make a new work, I had to use something that already existed. Because of the way the building moves around it’s cut up. It wouldn’t have worked to take one picture and stretch it out, so I knew that it had to be like a moving story, and I was so thrilled with this commission. I was very happy with what I came up with. I wanted it to feel like this seamless space, like one continuous room, but made up of different images. It ended up being seven different works that were cut up, expanded and seamed together, and the reason why I said yes to this commission, every time I see the picture it makes me happy—I’ll use a story to talk about this. Daniel Palmer, who I had worked with many, many years ago when he curated a two-person show with me and Doron Langberg in the basement of a coffee shop in New York,7 said he was in a cab driving by MOCA and the driver was Nigerian and the driver asked him, “I pass this building all the time. What is it?” [Laughs] And Daniel said, “It’s the Museum of Contemporary Art.” And then the driver started telling Daniel about the work on the façade! He said, “The woman in that picture is Dora Akunyili and she was this Nigerian woman who was in charge of the FDA and she did this and she did that,” and Daniel was just in awe. He was like, “I know the artist, she’s my friend, but I didn’t even know all these other aspects to it.” And I feel like that’s why it was so important to just have a building like MOCA be covered with images of Black people in a space that historically has kept out people that society had marginalized in other ways—Black people, women, LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, and all of the marginalized groups. So to take this kind of ownership over that space was very important to me. But also with the public projects, just thinking of how there are demographics that have been kept out of going to museums maybe because they haven’t felt welcome in it and—this is making me think of an incredible episode of Here to Slay, which is a podcast with Roxane Gay and Tressie McMillan Cottom, when they had Kimberly Drew come to do a discussion with them and they were talking about this feeling that a lot of Black people have, this feeling that the museum is not really a space for them. I know a lot of museums are working to change it, but it has to do with the histories and how when people walked into these spaces they didn’t see themselves reflected, they didn’t feel like they mattered in this space, so then why should you keep going there? I mean Kerry James Marshall had his “Mastry” show at the Museum of Contemporary art here [2017], Helen Molesworth brought it in. Phenomenal show. I saw it three different times and every time I was there the museum was packed with Black people, so, if you create a space where they feel welcome, they will come! And so I had this desire to reach a more diverse audience, especially people who do not go to museums for various reasons, so I’ve been happy with the outdoor projects.

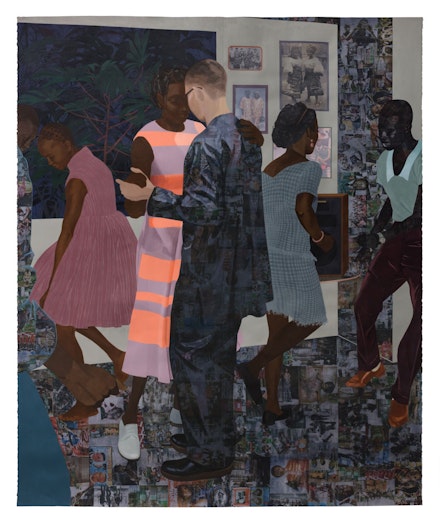

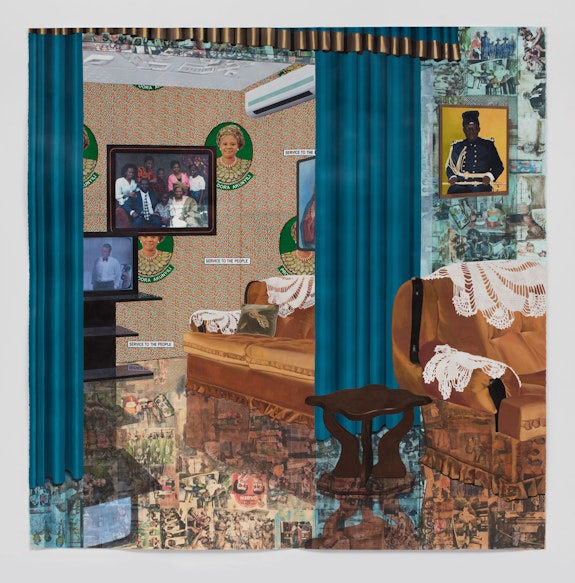

Rail: I don’t think I’ve ever had an artist be so ecstatic about what was clearly a commission that you had to put together really quickly and you had such a wonderfully positive experience with it. [Laughter] It’s magnificent. I wish I had seen it. I think of the history of Los Angeles and the Great Wall of Los Angeles with works by so many different artists overseen by Judith Baca—there’s such a history of these kinds of murals there, which are meant to connect with a broader audience that doesn’t necessarily ever set foot inside the doors of a museum. You also did a commission at Brixton Station, the Underground station in South London, which you could see as you come in off the street and as you go down the stairs to enter the Tube, and is the work called Remain, Thriving from 2018 which was a temporary installation, right? It’s no longer there.8

Akunyili Crosby: Yes. It’s down. I was invited by the London Underground to do a piece in Brixton. And Brixton is a very complicated area because it’s the place where a lot of Caribbean immigrants settled when they came to the UK right after the second World War. London had been bombed out and they needed people to help rebuild, so of course they needed manpower. What they did was they reached out to the colonies and they asked people to come help them rebuild and a lot of Caribbean people moved to London and they helped rebuild and of course they dealt with terrible stuff—racism, nobody would rent houses to them, people would not give them jobs, they lived in terrible living situations. So a lot of them went to Brixton and really formed a community to support themselves, just this feeling of “we have to do this for ourselves because they don’t care about us.” And so Brixton was just this thriving, incredible place. In the ’80s there was an uprising, very similar to what happened in Ferguson and is happening again. A police killed a Black British citizen and there was an uprising, which created this myth of Brixton being very dangerous. But what’s happening now is Brixton is getting very gentrified as people are finally realizing, “Oh my God! This is an amazing neighborhood! It’s right next to the Tube,” which in London is incredible. And then the Black people who have stayed there for decades and have put their sweat and blood and tears into this area and have made it thrive are being pushed out. So there was all this history of Brixton and there was also the stuff that was happening in London with the Windrush Generation, the Caribbeans who came after World War II to help London rebuild. They’re called “Windrush” because they came with this ship called the Empire Windrush. So now, some of them, their grandchildren are being denied citizenship, and they’re having to prove that they’re British. It’s horrible. They’re getting deported, they’re being kept out of school and social services and healthcare. I mean, it’s like the same shit all around the world! Sorry that I have to say that—

Rail: Yeah, same as here right? Boris Johnson and Trump are of the same cloth.

Akunyili Crosby: The same everywhere, this hatred of immigrants and Black people and Brown people. If your grandparents came with the Windrush and you’re born in London, you are a British citizen and you don’t question it. And if you don’t travel you have no need to go get papers. And so what they did is that they actually—it was very deliberate—they instituted this rule, frustrating people so that they will not stay if they are undocumented immigrants. So it’s like you can’t use healthcare unless you show your papers, you can’t go to school unless you show your papers, but if you had to go to apply for papers then you don’t have it! Then some of them don’t have documents that their grandparents had, I mean it’s really terrible. And also Brixton has a big African population. Whenever I went to London, Brixton is where I went to buy my cool African sneakers and African fashion. So when I got invited to do this, it was a very tough ask because people always talk about people from another space making work about the space. I don’t think the question is you can’t make the work if you are not from that space, I think the problem people have is when you don’t do it well and when you don’t do it respectfully and so I was so nervous about this project. I just felt I wanted to do it right. I didn’t want to do something like [Jeanine Cummins’ novel] American Dirt where you’re talking about something you’re not qualified to talk about, and so I took months off to do research on this project. I went to Brixton twice. I stayed there for a while, I studied at the Black Cultural Archives, I talked to a lot of British artists. There’s a wonderful Michael McMillan book called The Front Room—so this is actually based off a British front room, which is like this architectural style you see in houses, and so this is an image that was for that station. And with this, all the transfers are from Brixton, either contemporary or a lot of historic pictures from Brixton that I got from the various archives I went to when I was there.

Rail: The front room is the key room in these kind of row houses, where everyone congregates and they’re around the fire or the record player there. There’s always these iconographic indicators of time in your work.

Akunyili Crosby: Exactly!

Rail: Everyone needs to notice these things.

Akunyili Crosby: Yes! So I was looking at photographs by this artist called Neil Kenlock and so many people pose next to the record player. It’s very like Malick Sidibé in the ’70s where you had to show off your goods to show that you were cool, so that was like my little wink or reference to that.

Rail: And it also falls under a British tradition in Art which dates back to the 18th century, called the “conversation piece,” which was essentially portrait painters, instead of doing portraits of single people, which cost too much for some of their patrons, they have the whole family gather in a single painting. The Yale Center for British Art has plenty of examples of these by Arthur Devis and other artists. It sort of nicely fits into that, but brings it into a natural, domestic environment here in Brixton. It’s interesting to hear you talk about the Brixton uprising through the lens of what’s happening now. Of course, they’re usually referred to as the Brixton “riots,” but again here you have a situation where someone was killed by police and then there was a protest, and then things went bad because of police activity, so to call it an uprising seems like a necessary, sort of historical, determining factor in rethinking all these kind of events which happened in the past.

Akunyili Crosby: So many Black British people passed through that station every day. And I know it’s the same here, just people that have thrived in spite of so much opposition, in spite of the government working against them, the institutions working against them, their neighbors working against them! And the government rule was called “Leave to Remain,” that’s like a permission to remain, so I kind of wanted to play on that. Like they will remain, they have remained, and they are thriving in spite of this.

Rail: A monument to perseverance.

Akunyili Crosby: Yeah! I think a lot of my work is affirmations or affirmative. I wanted every time people walked down for them to be like, “You know, you guys might be systemically pushing us out, but this is our space!” Like, “This is us. We built Brixton!”

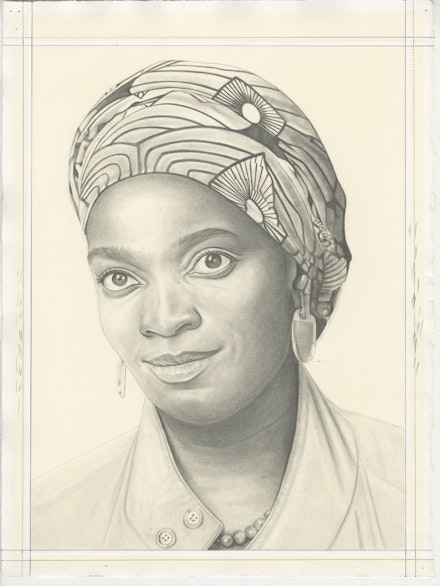

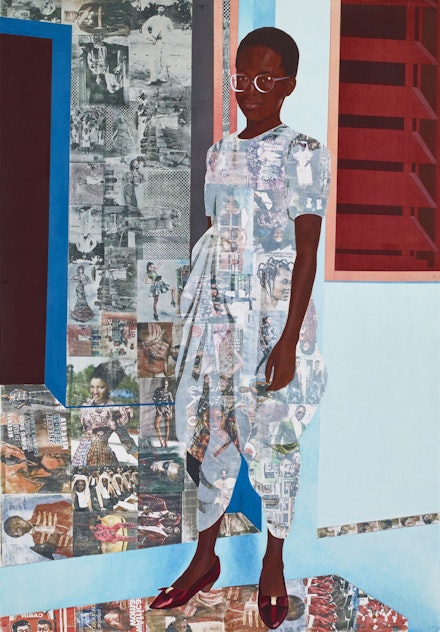

Rail: Let’s look at some of your works, such as “The Beautyful Ones” a series dating back to the mid 2010s. They are largely paintings which are produced from photographs and they have this similar motif, upright portrait format and using the transfer technique. This one is series number four from 2015.9 This might be a good work to sort of help us unpack what you do and here is presumably this source photograph from which you derived this image.

Akunyili Crosby: Yeah, so I have a series, I think right now there are nine of them. They’re all of little children, they're all the same size apart from one, they’re all kind of in the same space within each work, looking straight at the viewer. They’re the only things I have that are pretty much straight portraiture. A lot of them are based on family pictures. The Beautyful Ones” Series #4 is based off my sister’s first holy communion from when she was a child. I give winks and nods to people who I like. The title comes from a very popular Ghanaian novel called The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born [Ayi Kwei Armah, 1968] and for these—thinking of affirmations— I feel like I’m saying hopefully the beautiful ones have been born and they are my generation because, The Beautyful Ones was written in my parent’s generation, and it was about the hope that generation had about how things would change and be better after various West African countries became independent, but sadly that didn’t happen. In Nigeria, we just ended up having military dictator after military dictator, and corruption and everything just went down the drain. But there is this renaissance happening so I’m kind of claiming it for my generation, like the beautyful ones have arrived! So, this is my sister in her confirmation dress and the bench and the window in the back are actually pulled from pictures from my grandmother’s house in the village, and the doll on the bench is a Clonette doll. I felt like a picture of somebody in a white dress doing some kind of first holy communion stuff is not specific, there’s no specificity to it. It can be from the Southern part of the United States, it can be from a South American country, so I was thinking of something that had more specificity to it. I found myself wondering what toy would we have played with when we were young and I remember these dolls [laughs], and I spent a lot of time online trying to find them and then once I found them—the history was so fascinating because when I was trying to research it, I just assumed these were designed in the UK and sent to us as many things were—but then what I found out was that they were actually designed and made in Ghana, and they were kind of a contemporary version of the Akua’ba dolls. It just shows how wide-reaching white supremacy is, like these dolls are being made for use and consumption by African children, but they have no connection to us, this little Caucasian girl holding I think chrysanthemums, which is a flower we do not have [laughs] and a teddy bear. But most of us used these dolls when we were young, and of course I’m always interested in the things that speak to colonial and post-colonial commerce. So from thinking this way, dolls maybe designed in the UK, maybe made in China or somewhere else, which are then sent to people in West Africa only to realize that they were designed in Ghana based off of traditional Akua’ba dolls that were wooden, made for consumption by West African kids and then the next step to this, which is very fascinating, is that these are now very big collectors’ items within interior design circles in Europe.

Rail: And it’s interesting also with work like this, that it becomes, as you talked about, a part of kind of your vocabulary of imagery. So "The Beautyful Ones" Series #1C from 2014 is your other sister correct?10

Akunyili Crosby: Yes, my eldest.

Rail: Your eldest. And if you notice, on her right shoulder you put a transfer of that source image for the other work, The Beautyful Ones Series #4 (2015) so there’s a wonderful sort of continuum that runs throughout your work, and I think the more people look at it the more things become recognizable, and the way you have sort of claimed all these images, not just something which is autobiographical, but also the way you’ve adapted these kinds of pop-cultural things, which were brought into Nigeria post-independence and in your youth, and turned it into something of your own. It’s a radical gesture, it really is.

Akunyili Crosby: That’s the plan! Thank you for pointing that out and I keep talking of how there is this lexicon that has been forming in the work and I get very excited when multiple works that show this at once because you can actually begin to play a game [laughs], kind of trying to see where things came from one work to the other. Yeah, lots of winks and recurring themes and recurring pictures and inside jokes and things like that.

Rail: Related to the story you told about the cab driver in LA, you’ve talked in other interviews about the idea of developing a new audience for your art. That also is a radical gesture. Avant-garde artists have been trying to do that since the 19th century, the idea that certain people will understand these works better than the “normal” audience for fine art, if that makes sense. How do these works then become accessible to people in Nigeria, to young people in Nigeria, or across Africa really?

Akunyili Crosby: I think what really helps me develop this way of working, this kind of thinking of bifurcated audiences, was another class I took at Yale on African literature where we read Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God [1964]. I had read Achebe my whole life, but just reading it again in graduate school with these phenomenal professors and co-students trying to analyze it, he’s doing this thing where he’s playing with language, where in some chapters he’s kind of using this language that we’re used to seeing white people use to write about Africans. It’s very stiff, very, very condescending, racist language. Then, in certain chapters, we get the point of view of the Nigerians where he’s within that space telling their story and it actually creates a contrast between both languages. There’s such a damning critique of writing about the writers that came out about Africa. So what happened when I went to class for the Arrow of God discussion was I was so excited to go and talk about this. I always say reading Achebe for me is like going home because when we get to those chapters when it’s coming from within the space, even though it’s written in English, a lot of the speech is directly translated from Igbo, my language, so I actually hear my language in my head because speech patterns are different—there’s specificity to speech, the way we phrase things in Nigeria is very different from the way someone would phrase something in Mississippi, very different from the way someone would phrase something in the UK! Language has specificity to it. So I remember going to class and I was so surprised when other people in my class had a very different experience from what I had. They enjoyed the book. They could analyze it. But they felt removed from it. Whereas I felt within the space of the book and that was when I really started to go back and read Achebe and try to get down to how he was doing what he was doing because I felt like if I figured it out I could extrapolate from that and use it in art.

A lot of the work is about the painting tradition I came out of, which you have to remember is the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. We were taught the way painters were taught to paint a hundred years ago, we did paintings from life, we did paintings from the cast, and we did paintings from models, morning till night, five days a week, for two years. So that is the tradition I have. That comes across in the painting. There is a lot in these works that speaks to painting and color mixing and surface and transparency so there is that audience and then there is a whole lot of discussion that has to do with having lived in Nigeria at a certain time and that was just like a discussion I felt, after having lived in America for a while, I hadn’t seen. You know, like if you are an immigrant in the United States you get some really ignorant questions that show how very little people know about anywhere outside of the United States, and I just felt like I wanted to show the life I had lived—the Nigeria I know—and go back to and experience it in various ways.

Rail: That totally fleshes it all out. The idea that someone will then discover it and will understand it in a way that you understood literature.

Akunyili Crosby: And if you’re a painter, you will—I put a lot into these works to engage with painters. When I make this work I’m actually thinking of someone like, one of my good friends, Doron Langberg, who’s a phenomenal painter. He’s like the person I think of. I want to engage a painter like that or Catherine Murphy or you know, those painters you look up to, but then there’s also this part of myself that wants to engage people who have had that experience that I had growing up in Nigeria. For me it’s people who have the experience of the village, people who have the experience of the town, people who have the experience of Lagos, so that’s also like split up. So you’re looking at a work of mine, and there’s a transferred picture of someone like Sani Abacha, who was our president and died right before I left Nigeria. If you don’t know him, you know that it’s a reference to some military person. The African military dictator iconography [laughs] is so well known—the military hat, the glasses. If you see the picture, you’ll probably figure out that he’s a military dictator, but if you’re Nigerian, you know all the baggage that carries and the journalists he killed and just how tyrannical he was.

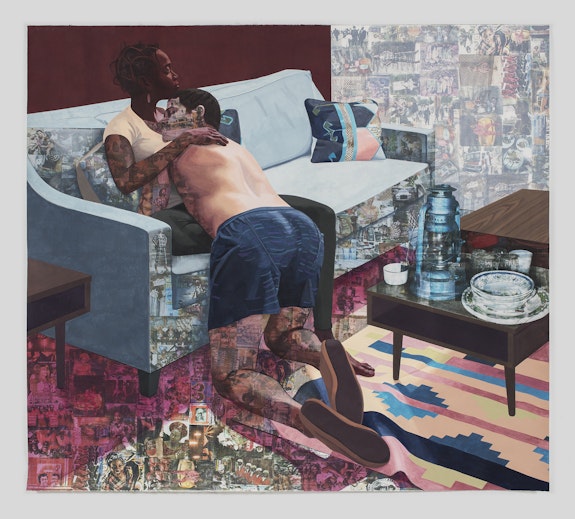

Rail: Let’s talk about Nwantinti from 2012 and the way that you develop characters in your work, the way that so many of them come out of your relationship with your husband, Justin Crosby, who is a sculptor, whose work I also find really interesting and they sort of hang in the balance, and there’s tension—a lot of things you’re both kind of dealing with from very different visual angles. But when I look at a work like this wearing my art historian hat, which never comes off, I think about a wide range of images and works from the history of European art which you are obviously aware of and accessing and repurposing, let’s say. From Manet to Walter Sickert to Yinka Shonibare’s Fake Death Picture (The Suicide—Manet) from 2011, just a year before your work, so when I see these things, I think about these kinds of works and I think of Vuillard, the Nabi painter, and these kinds of things which seem so related but of course that only gets me so far, right? Because I don’t know the Nollywood film history, right? I don’t know the history of Nigeria, I don’t know the African music from the 1980s. I know a little bit of Mali music, but stuff like Highlife from Ghana and “Sweet Mother” and things which you talk about in interviews—it’s that part of it which really is equally gripping, the idea of I want to learn about these things because they clearly come into the whole cholent or stew that you’re making here in these kind of extraordinary, visually gripping pictures.

Akunyili Crosby: Yes, and thank you so much for making all those connections. So there are lots of images of people draped over beds and I had had those in my mind for years, so this is one of those that proves that. I did this in 2012 but there was a day I found an old sketchbook from when I was at PAFA, which would have been 2005/2006, and I was looking through the sketchbook, and I saw a drawing of this, it was like a stick figure drawing, but it was on a park bench. So for a long time I knew that I wanted to do… ah, it’s like how much should I confess? [Laughs] I’m a romantic! [Laughs] Now it’s out there! I wanted to do something that was… sweet? I know people kind of might cringe at it.

Rail: We can talk about sweetness and we can talk about beauty. That is not anathema to the Rail.

Akunyili Crosby: I didn’t feel like I could do it or I had permission to and I finally said “Eh! I’m gonna do what I want to do!” So this is the image I had thought about for years, but I kept resisting because I felt it was too sweet, it’s too sweet, and I was thinking of this draped-over-bed imagery you see a lot. I was thinking also of the pietàs, I was thinking of this very sculptural aspect of composition that was very bottom-heavy. It almost felt like a pedestal and then everything builds up into this triangle area, and so I felt that if I was going to do this, I was going to just dive in and embrace it fully, but I didn’t want it to be known to everyone, so there’s a little bit of a wink in it, but when I was young there was a very popular Nigerian song called “Love Nwantinti,” and the album cover is actually transferred multiple times into this work. So “Love Nwantinti” kind of ended up becoming part of the lexicon of eastern Nigeria where I grew up, so usually if you’re doing PDA or being super sweet, that’s what people say to tease you, like “Oh my God, love nwantinti. Stop already!” [Laughs] So, I didn’t want to put love because if you know the reference once you hear “Nwantinti” then you’re like “Ugh! God, yes I know what this is.” So once I had that idea I wanted the transfers to have a lot of music references, so this is a very music heavy transfer, thinking of very popular musicians when I was growing up like Oliver de Coque and all the way to contemporary Nigerian musicians like 2face, D’Banj, P-Square. References to Nigerian Idol. And I wanted a lot of the transfers to be red. I wanted to try to make an all-red piece because I had seen a Degas painting at the Philadelphia Museum that was just multiple types of red, and I wanted to challenge myself to do something like that, so that’s a little bit of the backstory for how this piece came about.

Rail: I think it’s a wonderful piece and romanticism is good, I mean we don’t ask Wong Kar-wai to apologize for In the Mood for Love, you know? This is a timeless subject and with those kinds of films and the musical references it comes together in a really heated way in this kind of picture. It works beautifully. Looking at Nwantinti or Ike ya of 2016, do you think about the position of the viewer or the use of perspective in the way that it allows you an entry into the picture? We talked about the one painting, Mama, the one that was on the side of the building by the Whitney as a picture which seems to me as one of the few that has a real one-point perspective-in-the-center orthogonal system, but it’s not typical. Like these, most of them are on an angle.

Akunyili Crosby: When I work in my studio I have strings on walls that I use to do all those things. The perspective has always been important to me because something people are not aware of until they come to a studio visit or they see images of a work in progress is how cobbled together the images are, so I want to create these spaces where you feel you just passed the window and saw this scene, or looked through a doorway and saw this scene, so it looks like a feasible picture that can exist, but it’s not. Ike ya is actually made up of three different photographs, some are made up of a lot more, and the perspective is what helps me hold it all together. I can make anything believable if I make it follow the rules of perspective I’ve set down for that particular composition. I use perspective to unify, but something I started doing in 2013 is actually intentionally messing up the perspective, because I would spend days plotting out the whole, gridding out most of the piece so I can start putting in extra tables or walls or doorways and all that stuff. But I started shifting perspectives either between two different panels or even sometimes within the same piece so there was a very slight destabilizing effect for the viewer. When you’re looking at certain parts of the painting, you’re very aware of your relationship to that part based on the perspectival choices, but then you look over to another part of the painting, and where you’re standing doesn’t make sense anymore.

Rail: I see.

Akunyili Crosby: So that came about from feeling like I didn’t just want to make these windows or these pictures that you look at and you kind of get this narrative I’m trying to put down. I wanted the viewer to have this feeling of the ground not quite being stable underneath them, just to destabilize them a little bit and then they have to shift their perspectives, because that’s kind of what you do as an immigrant, you’re constantly shifting like straddling two places and viewing everything through two separate lenses. But sometimes it’s so subtle that people don’t even pick up on it so I’ve been wondering should I make it more obvious? But I like it. I like how subtle it is.

Rail: I think it harmonizes with the way you work with the images, many of which are not comprehensible to some people, but are comprehensible to other people.

Akunyili Crosby: Exactly!

Rail: And then you are doing it compositionally.

Akunyili Crosby: And I think the feeling is there, when people talk about the tension in the work. I think that’s why. And I don’t want things to break apart or fracture—I want the space to be believable. You become aware of it when you start thinking, “Okay, what happens if I extend that table?” kind of stuff there. Aha! That doesn’t make sense in that space! But that’s sort of when artists start breaking down the constructed space.

Rail: Can you say what the title Ike ya means? Because I haven’t been able to find that anywhere.

Akunyili Crosby: I have never said it! [Laughs]

Rail: Ok, there you go. [Laughter]

Akunyili Crosby: I’ve actually never said it and it’s intentional so this is one of those inside jokes for people who speak my language. But actually I’ve said it, but I’ve said it different ways, so I-K-E, Igbo is a very tonal language and the easiest way to explain this is we have one word that is A-K-W-A and depending on how you say it, it can mean four different things. So there’s Akwa, Akwa, Akwa, Akwa! So that’s “cry,” “dress,” “bed,” “egg.” [Laughter]

Rail: Excellent.

Akunyili Crosby: So this is what happens when the British come and put their language system on a language that didn’t evolve that way. So I-K-E can either be Ike, which is “bottom,” or it can be Ike, which is “strength.” And Igbo is not a gendered language so we don’t do his/hers, we just say “ya” which is like theirs. So it can be “ike ya” which is can be “Justin’s bottom” or it can be “ike ya,” which is like “their strength.” You don’t know if it’s his strength or her strength, so you really get like four different things it can mean based on what is said. So this is just an inside joke because that’s a big conversation that happened in the late ’70s into the ’80s within African literature where there was a group that was saying people should stop writing in the colonizer’s language so stop writing in English, stop writing in French, and then there was the other side saying it’s ridiculous to make this demand of people. And so Chinua Achebe was on the side saying “No, you can’t tell us to stop writing in English, because even though English is inherited for us, we’ve actually got to the point [laughs] where we’ve taken ownership of that language and we have a variant of it.” So it’s not that we shouldn’t write in English, it’s more like write in the English that is specific to you and it will speak of place, and I do agree with that, so this is my little addition to it because reading in Igbo is not even the answer because reading in Igbo is actually… sorry [laughs] now I’m going extra into this! But this makes me think of Kwame Anthony Appiah’s Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers [2006], where he talks about culture as an onion and it’s like you can peel it and there’s more layers and the question becomes “how far back do you even go?” So, if you’re saying, “Oh, the solution is to read and we should write in our local languages,” instead of writing and reading in English, but writing in our local language is actually not tradition. That came with the British and there are these moments that expose that. I speak Igbo fluently. I hate reading it. And the reason I hate reading it is that it’s not meant to be read. When you read it, it takes twice as long because you have to read every sentence twice. If you see a word, because it’s not tonal, you don’t really know what version they are talking about, so you read the whole sentence then you get context, then you have to read it again, and then you’re like “Ah! That’s “strength” and not “bottom,” I get it now!” [Laughs] So this is just my joke: “There you go! I’ve written it in Igbo, are you happy? But you have no idea what that is until I say it but I’m not going to say it. [Laughter] Read it!”

Rail: And there are no symbols or vowels or whatever that tell you how to—

Akunyili Crosby: There are intonations, but people don’t really write in it. So if you wanted to do it right, you would actually go and put tonal marks. Like “up, up, down, down.” You have to put tonal marks on every vowel.

Rail: Oh my, okay. Everything you’re doing connects! [Laughter] That’s the wonderful thing about it. It is the layering and whether it’s the composition, the titles, the overlay of the images, or furniture or whatever, it’s all pretty comprehensive. It makes a kind of unified sense, even if it’s impossible for some people to pick it apart.

Akunyili Crosby: To link it all, yeah. Tradition is fluid and it changes. We shouldn’t just lock into things, like, “No, this is what we should do.”

Rail: Yeah, excellent.

Akunyili Crosby: Because that breaks apart once you start examining it.

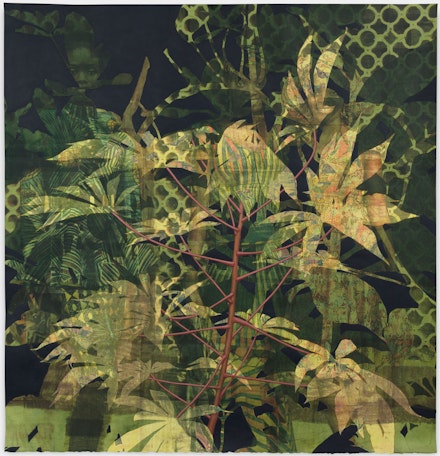

Rail: Let’s discuss the more recent works and what you’re up to.

Akunyili Crosby: I moved to Los Angeles in 2014. I’ve never had a green thumb, I’m that person who will kill a cactus. But I have a good friend, Mike Richards, who went to Cal Arts with my husband, and every once in a while he will come and help me out in the studio. And there was this one summer when it was so hot, I had to move the work to the living room. Mike came over to help and he started asking me to let him work in our garden because the garden was just weeds, it looked like an abandoned house [laughs] and he loves gardening and he’s absolutely transformed it—but just through working with him in the garden and going to different nurseries and talking to different plant enthusiasts, I have become a garden person. I love plants and I think what it was, I just realized the rich histories plants carry with them. So my studio used to be in East LA and Mike came in once and said, “Oh, your neighbor has this very beautiful flower!” And he just talked about this flower all the time, and finally we were walking by and the neighbor was there and we started talking to the neighbor and then it turns out the plant is called plumeria and the neighbor had moved to Los Angeles from a South American country and they were telling us that plumeria is very plentiful there. Then after that conversation I really started paying attention to plumeria and I noticed like almost every house in East LA—it was everywhere in East LA! You go to certain neighborhoods, you don’t see a lot of plumerias. East LA is predominantly Latinx—so it made me wonder if people brought plumeria with them to this area where they settled historically and that’s why there’s so much plumeria? It was tied to home? It reminded them of home? But really doing research, going to Huntington, talking to people who worked there—Huntington is a big botanical garden in Pasadena—

Rail: Full of British art!

Akunyili Crosby: Yes! [Laughs]

Rail: I got engaged there. [Laughs] That’s where I proposed to my wife.

Akunyili Crosby: That’s beautiful!

Rail: There’s my revelation.

Akunyili Crosby: Yeah, I went to Huntington last year and they have a lot of plants from all over the world. Normally when I’m trying to look for plants, I spend a lot of time online, but finally I just took my big camera there, we had a white bedsheet because I want the plants silhouetted so my husband will hold up the bedsheet and I take pictures, so now I have an image bank of plants. But just talking to people at the Huntington and people who study plants, you realize when people move they move with their plants, so you can actually use plants as a way to map movements across the globe and studying plants actually you realize like there are things called cosmopolitan plants. [Laughs] I think a lot about cosmopolitanism in my work, this moving across the globe, and there are these plants that are cosmopolitan because they are found everywhere and of course there are native plants that are found in just one area, so I’ve been doing a lot of research in plants and really playing with those two together. Like, what does it mean if I create a garden scene that has cassava? I studied this particular variety of cassava that I only have ever seen in Eastern Nigeria. Not just in Eastern Nigeria, it has even more specificity to it—I see it in rural parts of Eastern Nigeria because it’s very easy to grow, the tubers are very big, and you can make a lot of different foods from it. It is the base of rural diets. So when I was young I always knew I was getting close to the village once I started seeing cassava farms. Thinking of the specificity of that—what does it mean if I make a work with cassava next to an Indian rubber plant, which is a plant that is native to India, but has become naturalized to the United States and different parts of the globe? Doing research into things like tropical almonds, into plants we have in Nigeria that I can’t even find because I don’t know the scientific names for them and using these in compositions. I did a piece recently where there’s a window looking outside to a plant scene and it’s cassava and fluted pumpkin, which is found in Eastern Nigeria, and a tropical almond. This new piece that I’m working on is to imagine the space where we’re seeing through the window—the other side of the wall—so it’s a character based off of me, I’m holding my one-month-old child who has on the Studio Museum “Black Is Beautiful” onesie, and we’re just surrounded by this invented garden of Madagascar jasmine, a fig plant, and other different plants.

Rail: I was going to ask you when the kids were going to make an appearance as characters—

Akunyili Crosby: [Laughing] First time!

Rail: This is it right? The time is now.

Akunyili Crosby: Yes. So I started this right before the safer-at-home, so it’s been a very slow progress. Trump’s election really threw me for a loop and left me quite depressed for a while. I couldn’t work for the longest time because for me what does it mean that he was elected? I felt like a country I had settled in and called home turned around and rejected me and said, “We don’t want you here.” Just being Black, being an immigrant, being a woman, just hitting a lot of the zingers that he hates. Just finally seeing the white supremacy in the country. What I’m trying to get to is constantly shifting. Right around the election time I realized that I had been in America long enough that I had a stake in this country. I’m very plugged-in to my local elections and politics, but that wasn’t always showing up clearly in the work. So I actually did the series “Counterparts” [beginning 2017 – present], where I started introducing a lot of pictures from the United States into the work. As an artist, I think what you do is that you make something and it comes close to what you want, but it’s never quite right. I mean, it’s never quite right because we’re very complex, multi-dimensional people, and it’s hard to gather all of those thoughts in one piece. It always falls short just a little bit so then you try to make another work that amends that or pushes it forward. I never feel that any specific work says exactly what I want. I feel on their own they do an aspect of what I want. The analogy I have for myself, with my work, which is the one where I can stay a little bit calm and not get too anxious and unable to work is to think of them as chapters in a book, and it’s a book that is still ongoing. So each chapter hits a different note, but the full story is actually in when they all come together.

Rail: I think it totally did. You also, as you have mentioned, grew up under a military dictatorship. It must be doubly difficult to live through what we’re going through in this country since 2016.

Akunyili Crosby: Yeah. I read something that was written by a Nigerian that was saying, “We’ve seen this playbook, we know how this plays out.” I remember talking to someone once, years ago—this was before Khashoggi was killed—and I was telling them, “My god I’m seeing so many similarities to Nigeria.” This flaunting of law, you get to a point where you can do anything because you act like a king—there’s no accountability. I said something along the lines of, “This is so eerily similar. The only thing that hasn’t happened yet is they are not disappearing journalists.” And then of course a few weeks later Khashoggi is killed. He wasn’t killed by Americans, but they also just kind of went [shrugs]. I think a lot of people who grew up in dictatorships have been just screaming about how this is like a replay of what happens. The past few years I’ve had so much anger that it has been very hard to work because sometimes you just want to roll up a piece of paper and scrawl obscenities all over it. Then what? I think it is so hard because we have to process what’s happening, you almost have to come out on the other side and be able to look back, but it’s hard to process because what’s happening just keeps piling on. Even before the pandemic started, it feels like you’re just beginning to breathe from the terrible rule they’re trying to establish that is terrible for immigrants and Black people but then there’s something else that comes. How do you process this? How do you make work in this? Sometimes when the anger is so great you can actually limit the work and it can breathe and live and grow beyond the specific time, so I’ve been trying to have a lot of patience with myself and realized this pandemic has been happening since January and it just started to finally move along! It has just been a lot of sitting at home, reading the news, and cursing my phone, and I’ve just realized I should be more generous with myself, that this is a year unlike anything that we’ve experienced—the solution will be different for different people, and you just have to figure it out for yourself. I am still trying to figure out how I navigate it. The main thing is how can you navigate it for yourself? We have to be able to pivot. You can’t work the way that you had been working before the pandemic. I realized I had to try something different. So I have a few panels that are about this big [gestures] and I’ve been painting in my backyard, next to the washing machine [laughs]. I know they might never be seen, they might end up being terrible, but it just lets me work, it lets me experiment and try new things that don’t feel as precious, so I can also see where I take the work from here, because it almost just feels like this past year something has cracked open, and I feel like it would be weird for the work not to respond to that. How it does that I’m not sure yet. As artists we actually figure things out through working. One of my mentors from grad school always says, “work begets work.” We can read a lot, we can study a lot, we can do all that stuff, but in the end you just have to sit down and make something. And it’s in the making of something that a lot of questions are answered, and you figure out the next thing, and the next thing, and that’s how ideas are developed and pushed forward. Even if it’s just little experimental things that will never see the light of day, it could be something to do in your room in a little space you have as a way to cycle through ideas and not making a finished work of art.

Rail: Let’s finish by talking a little bit about architecture and how it relates to your current work. The idea of a kind of ’60s/’70s, mod feeling, which is familiar I think to people in this hemisphere in traveling to Latin America, the Caribbean, or South America, and seeing these kinds of constructions in countries, many of whom got their independence and then were trying to kind of at the same time be au courant and build international modernist buildings. Does that have any kind of element that comes into play in your pictures, which are so, I think, architectonic?

Akunyili Crosby: Architecture is actually something I think about a lot, but I haven’t quite turned it up as much as I would like to. Architecture in Nigeria is so fascinating. From colonial-era houses to places that were trying to look outside and show that they were part of current things, like a lot of government buildings are in that modern style, like thinking of the National Archives in Enugu. So that’s actually the thing I wanted to focus on when I go back home, is to go and photograph buildings, because they have such a specificity of time and also place. The architecture in the village is very different from the architecture in Lagos. So, I do a lot of thinking of architecture within the space, like inside the room, inside the building, thinking of what doorways look like in my grandfather’s house, as opposed to my father’s house in the village, as compared to our house in Abuja. Our house in Abuja was finished maybe ten years ago, so it’s like a different era of houses. You know, that era is more about looking outside again, so you’re seeing a lot of like Italian-looking ceilings as in Home: As You See Me [2017].11 So this is actually our new house and our old house. These are shapes that Nigerians will recognize. There was a time—even things like the floor design—there was a time when every house had tiles. You know, like those linoleum tiles. I’ve been thinking a lot of architecture, but I want to, especially now that I’m thinking of taking things outside or even when I use windows, I don’t want it to just be plants. I’ve been looking at a lot more houses and stuff, and thinking of the specificity of that in terms of time and place.

Rail: Are you thinking about doing some landscapes?

Akunyili Crosby: Not landscapes, but putting people outside. I’ve not bought it yet, but I know David Adjaye has a book that travels across the continent photographing buildings. I really think like architecture in the continent is very fascinating.

Rail: Absolutely.

Akunyili Crosby: It’s such a mix of different influences and the influences change over time. There’s a whole story there, I know. I’m figuring out how to bring it in. David Adjaye has done buildings all over the world, but in the last Venice Biennale I remember walking into the Ghana pavilion and it took me home. David Adjaye designed it—well first of all one of the artists actually had dried fish, not that you should put dried fish in your buildings, but it had dried fish embedded in the walls so when you came in there was this smell of the Nigerian markets or the kitchen when they are cooking stuff with stock fish. Smell in that case was such a memory thing that took you to a very specific place and then even the architecture, the space, took me back home. That’s the thing, when things work like that you might not even be able to articulate why it’s doing that but it is. I ended up talking with David because he was there and he was actually saying that they got sand from Ghana to bring to Venice to do it because the point he was making to them was this wall—which was kind of a wall covered in sand—if you made it with just sand from anywhere, yes, it would look like a sand wall, but it wouldn’t have that same effect. And I walked in and within a millisecond that effect he wanted hit me. It was like, “Oh my god I know this wall.” This sand is the sand I saw in houses. The word that I keep thinking and I tell people about is specificity. It takes a lot of work, it takes a lot of research, and almost it seems like wasted time because most people would never know, but if you get it right it hits people. When I research for my pictures I am looking for a lot of that. That specificity of things. So if you want to have biscuits it’s not just about having biscuits—which particular biscuit? What does it say, from what time, what is the image of it and all those things are tied to so much, and that’s where all that content comes in. It works. It really is like the magic of images that it’s hard to explain. [Laughs] And one way I think of it is, think of walking down the streets of New York, how sometimes you see someone and immediately in your mind you know “ah, that’s a tourist.” Within a second! It’s something about the way they carry themselves, the shoes they’re wearing, the way their outfits are put together—that is the power of specificity. It speaks to place and it speaks to time. Like how is it that when I go back to Nigeria people can tell that I don’t live in Nigeria anymore, even though I speak the language? And I always feel like if I can get to those things I can actually begin to speak. Because we all carry those things with us, it’s just being able to put your finger right on it. That word, cosmopolitanism, is always in my head when I’m working, difference next to difference—just like I hate the idea of assimilation as a prerequisite for being American. No. You don’t have to give up your culture. You just carry the stories that you brought with you and exist next to other people, and it actually makes for a richer world. I am thinking how as an immigrant you actually don’t leave your space and assimilate into this, it always comes with you. So you actually end up being a person who is multifaceted, and each facet is valid and important and unique and adds up to the wonderful unique person you are, and so the work is trying to speak to all that.

- The author would like to thank Ms. Akunyili Crosby’s studio assistant, Aileen Painter Kim, the Rail’s Malvika Jolly, Hanna Schouwink at David Zwirner Gallery in New York, Kathy Stephenson at the Victoria Miro Gallery in London, and Njideka herself, who is the most generous possible interviewee, and singularly expressive and engaging, as can be seen in the recorded Zoom conversation and follow-up questions at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0GrvzpBiirM2.

-

In the February 2018 issue: Jason Rosenfeld, “CATHERINE MURPHY: Recent Work,” Brooklyn Rail, February 2018, https://brooklynrail.org/2018/02/artseen/CATHERINE-MURPHY-Recent-Work.

-

For the exhibition Njideka Akunyili Crosby: Predecessors at the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, also seen at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, in 2017.