ArtSeen

Willem de Kooning:

Men and Women

and Drawings

On View

Matthew Marks GalleryMay 5 – June 26, 2021

On View

Craig F. Starr GalleryMay 4 – July 30, 2021

Although Willem de Kooning was one of the most eminent Abstract Expressionist painters, unlike his colleagues he is best known today for work that is representational, particularly the series of monumental seated women he painted between 1950 and 1953. This incongruity should surprise no one: critical discourse and artistic practice never quite match up, and de Kooning’s work is particularly diverse and changeable. His practice never stood in place for long, a sustained creative restlessness that is plain to see in a pair of exhibitions currently on view, one at Craig F. Starr and the other at Matthew Marks. The former show is a study in focused artistic transformation, while the latter emphasizes de Kooning’s dynamic unpredictability at every turn.

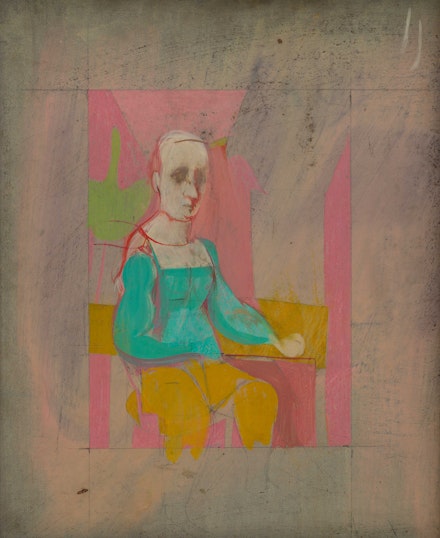

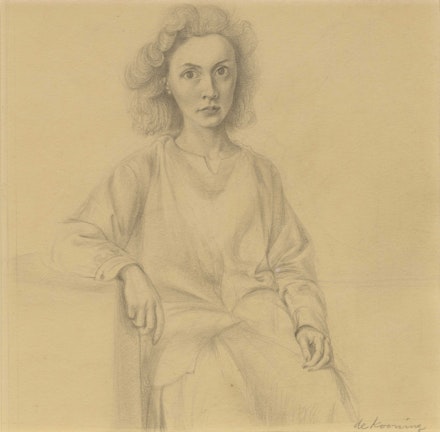

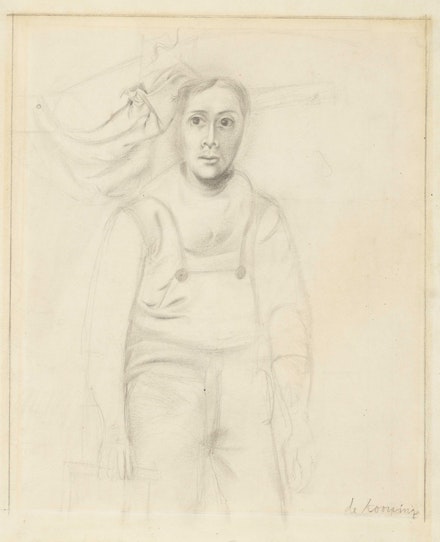

Craig F. Starr’s show is a lapidary selection of just six works executed across ten years, all displayed in one small room. The exhibition’s title gives men and women equal billing, but the active principle of the works shown here is clearly female—there are more women in evidence, and their forthright power decisively overshadows the two men who appear. We can see this already in the two drawings that introduce and frame the show: Portrait of Elaine (1940–41) and Working Man (c. 1938). Although both are sensitively rendered, the artist’s wife sits relaxed, confronting the viewer with a knowing and incisive stare, while the anonymous workman of the second drawing seems tentative, his body anxiously compressed. The nearby man shown in Figure (1944) likewise avoids engaging the viewer directly, his gaze downcast and his thoughts directed inward. Here de Kooning adopts a more abstracted formal vocabulary, as he has embedded his subject in an environment built from color planes inherited from the late Cubism so widespread in the 1920s and ’30s.

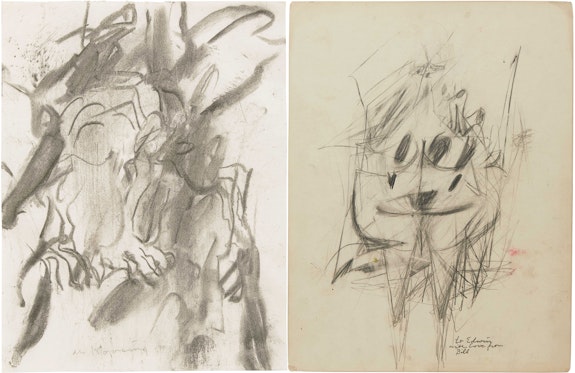

In the three remaining works on view, de Kooning explores variations on a single theme—groups of women—and pushes his visual language ever closer to abstraction. Untitled (Two Women) (1947) sees the artist reaching further back into the history of modernist painting, reshaping both figures and setting with a network of fragmented forms that recall the pioneering work carried out by Picasso and Braque around 1911. Although made fearsome by their anatomical reconfiguration, the two women are depicted here with extraordinary presence—the mask-like face of the figure on the right seems to meet Elaine’s gaze from across the room with an equally calm and contained self-possession. In the more legible of the two figures depicted in the adjacent Pink Lady (c. 1948), a similarly serene visage seems to peek out from within a frenzy of abstracted bodily geometry, but here de Kooning has returned to more naturalistic facial features.

Right: Willem de Kooning, Woman, c. 1950. Graphite and wax crayon on paperboard, double sided, 13 1/8 x 10 inches. © 2021 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

The last of the six works on view at Craig F. Starr, Untitled (Three Figures) (1947–48), features the most radical composition, filling the frame with a relatively continuous network of body parts become abstract forms (or, perhaps, vice versa). While Two Women most directly anticipates de Kooning’s monumental women of the early ’50s, Three Figures speaks instead to the famous abstractions he painted just before. In the all-over tissue de Kooning weaves from the three bodies pictured here it is hard not to see echoes, for example, of the tight angular lattice that lends Excavation (1950) its structure—the artist himself consistently denied any meaningful separation between non-objective and representational painting, always insisting on their mutual dependence.

To some degree the drawings on view at Matthew Marks suggest a similar trajectory, beginning with more naturalistic work of the 1930s and proceeding into less immediately legible styles. But even from the beginning, this exhibition shows us de Kooning’s ability to think in many directions at the same time. Not far from the gallery entrance is a carefully delineated and expressive portrait of Harold Rosenberg from the late 1930s alongside two contemporaneous works that clearly register the influence of Surrealist painting: an untitled mural study featuring a profusion of ambiguous biomorphic forms and a reclining nude whose blank features and slack limbs are more crumpled marionette than odalisque.

Moving deeper into the show we encounter several drawings, like Two Women (c. 1950), that are clearly related to the works on view at Craig F. Starr, but the exhibition at Matthew Marks shines brightest in its unexpected touches. I have always thought of de Kooning at his best as a maximalist painter—more paint, more texture, more confrontational vigor—but there are a number of drawings here that do extraordinary work with minimal means. Untitled (Woman) (c. 1975–80) dissolves the figure into a haze of smudged charcoal, but the image is nonetheless provided a flickering energy by sinuous lines that arc back and forth like sheet lightning in a thick cloud bank. In Man (1964), by contrast, de Kooning assembles a highly coherent character from just a few calligraphic marks, sketching in an active pose and an engaging, quizzical expression. Most impressive, however, is Leaves (1958), in which de Kooning renders a bit of foliage as a delicate linear network that is nonetheless charged with tensile strength. Looking at this image, which strips away the artist’s brilliant color, emphatic handling, and instinct for drama, de Kooning has rarely seemed more convincing.