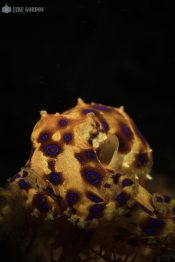

Photo: Luke Gordon

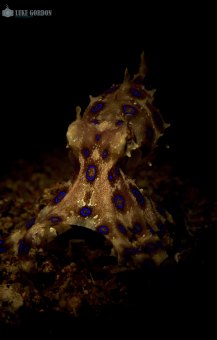

I am definitely not the first person to write about the Blue-ringed Octopus, and once you’ve seen one for yourself it is quite understandable that people get excited about them. Blue-ringed Octopus are probably one of the only invertebrates you can call “cute”. With their small size, interesting behaviour and iridescent blue rings they look like something out of a cartoon. Add the intriguing fact that these animals are also one of the world’s most venomous animals, and it becomes logical that people are interested in these critters.

Blue-ringed Octopuses are several species in the genus “Hapalochlaena“, depending on which source you check, there are anything between 3 to 10 species. They are all small octopuses, with the biggest one (Hapalochlaena maculosa) growing to only 15cm (body + arms). They are found from the centre of the Indian Ocean to the west of the Pacific Ocean. While their colours might make you think they belong in similarly colourful tropical reefs, they are actually more frequently found in the temperate waters of southern Australia.

A fact that is repeated very often is just how venomous these little guys are. So I won’t spend too much time on it here, but if you want to read more about it check out this link to learn all about the technical toxic details. The short version is: if you get bitten, you’d better hope to have someone nearby who is highly skilled in CPR. One of the more fascinating effects that occur when bitten is “locked in syndrome“, where you appear to be dead, but are actually still aware of what is going on. If that and near-certain death doesn’t stop people from harassing them to get a nice picture, I don’t know what will 😉 .

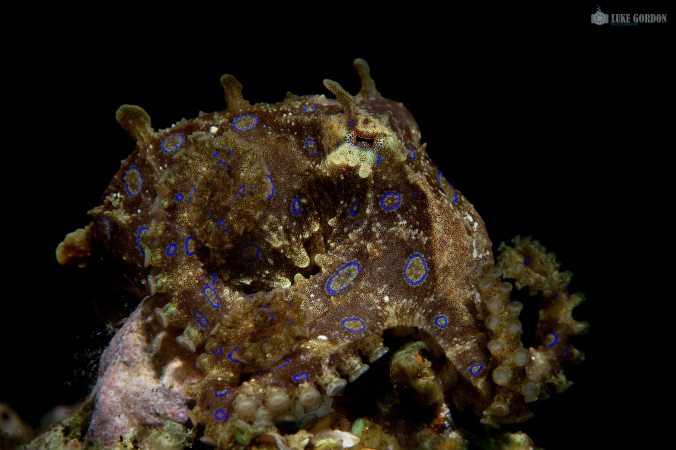

Photo: Luke Gordon

The most conspicuous features of the Blue-ringed Octopus, its blue rings, are actually hardly visible for most of the time. When you find one while diving and you don’t bother it too much, they look like any other well camouflaged octopus. The blue rings are a warning signal they only show when spooked or threatened. The mechanism of how they show those rings is a really neat one. The rings are pigmented cells that are usually covered by muscles that are contracted above them. It is only when the octopus relaxes those muscles that the blue rings show. Like a blanket that’s pulled away when unveiling a work of art. For more details, check out this paper.

Photo: Luke Gordon

One of the most interesting things I could dig up about this critter is about the way they mate. It turns out that Blue-ringed Octopuses can’t tell the difference between males and females! Males will try to mate with any other Blue-ringed Octopus they encounter, pouncing (that’s the technical term, trust me) on the potential partner and inserting their hectocotylus into the mantle cavity of the partner. It’s only after they insert this modified mating arm into the other octopus, that they can tell if their partner is in fact female or not. If the partner turns out to be another male, they amicably part ways, no harm done. In case they get lucky and their partner is a female, the male clings on for a long time: usually more than 90 minutes, but sometimes to over 4 hours! As a matter of fact, it seems the male tries to hang on as long as the female allows it, only breaking contact when forcefully removed by the female. If you are interested in the love life of small octopuses, you can read the original study here.

There is a lot more to find out of the Blue-ringed Octopus, such as the very basic question “How many species are out there?”. Considering that this animal is one of the most popular critters in muck dive tourism, it is surprising how little we really know about them. For my research I mostly look at fish, though I am always on the lookout to see what the best places are to find and study other interesting species. So who knows, I might just have a closer look at them in the future.

Photo: Maarten De Brauwer

Pingback: Valentine: Sex on the sand | Critter Research

Pingback: Critter Research