Overview

Cutaneous lymphomas represent a unique group of lymphomas and are the second most frequent extranodal lymphomas. [1, 2, 3] They can be defined as lymphoproliferative skin infiltrates of T-cell, B-cell, or natural killer cell lineage, which primarily occur in and remain confined to the skin in most patients, without detectable extracutaneous manifestations at diagnosis.

B-cell lymphomas account for the majority of nodal lymphomas, whereas primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) represent 20-25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Because CBCLs have an overall favorable prognosis, proper recognition is vital for appropriate therapy and to avoid overtreatment in most cases. The tumor type and the extent of cutaneous involvement are the 2 most relevant prognostic factors in primary CBCL. [4, 5, 6]

The diagnosis of CBCL is established by analysis of skin biopsy specimen, using histomorphology and cytomorphology, immunohistochemistry and phenotypic features, and genotyping and cytogenetic studies (see Workup of Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma). For those CBCLs that have a much better prognosis than their nodal counterparts, overtreatment must be avoided.

Treatments may include surgical excision, antibiotics, and radiotherapy. Treatment varies, depending on whether the patient has solitary or multiple lesions. Likewise, with primary cutaneous lymphomas associated with a poorer prognosis, treatment is different for isolated or grouped lesions than for multiple lesions (see Treatment and Management).

For for information, see Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma, and Cutaneous Pseudolymphoma.

Pathophysiology

The development of cutaneous lymphoma is only partially understood. Most probably it is a multifactorial and multistep process, with various etiologic factors intervening over a long period.

The disease likely begins as a hyperreactive inflammatory process. Subsequently, inadequate regulation of cell proliferation and defective oncogene and/or suppressor gene expression promote the transition from preneoplastic conditions to neoplasia.

The most important factors initiating cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) are the following:

-

Immunodeficiency disorders

-

Infections with oncogenic bacteria (eg, Helicobacter pylori in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT] lymphomas, Borrelia burgdorferi in cutaneous B-cell lymphomas) [9]

Epidemiology

The frequency of cutaneous lymphomas is 0.3 case per 100,000 population per year, with 10% (in the United States) to 20% (in Europe) being cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs), marginal zone lymphomas, or follicle center lymphomas (FCLs). One study reported a slightly lower rate of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma in Argentina compared with the United States and Europe. [10] The 5-year overall survival rate for most cases of CBCL is greater than 90%, except in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), for which the 5-year survival rate is 20-50%.

No significant statistical data are available for CBCL with regard to any predisposition based on race. However, with regard to sex and age, DLBCL is predominantly seen in elderly women.

Classification

Diseases formerly designated as reticulosis or reticulosarcomatosis are currently classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO)/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) classification (WHO-EORTC classification) for primary cutaneous lymphomas and the WHO classification. [11, 12, 13, 14, 15] Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) can be stratified in prognostically relevant clinical stages, but no generally accepted staging classification exists for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma.

In 2007, the EORTC published a revised tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system for non–mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome. [16] The value of this scheme has been proven by clinicopathological studies. [17, 18]

The WHO/EORTC classification of CBCLs includes the following categories [11, 12, 13, 14] :

-

Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT] type)

-

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma

-

Cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type and others

-

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma (MALT-Type)

Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL) (MALT-type) is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma, accounting for approximately 10% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Variants include immunocytoma and primary cutaneous plasmacytoma. Although it has been reported in children, it is most commonly seen in patients in their fourth decade. [19, 20] The prognosis of MZL (MALT-type) is excellent, with a 5-year survival rate of greater than 95%.

Synonyms based on classification are as follows:

-

WHO classification (2008) - Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma)

-

WHO/EORTC classification (2005) - Primary cutaneous MZL

-

WHO classification (2001) - Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type

-

Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification (1997) - Extranodal MZL

-

EORTC classification (1997) - Primary cutaneous MZL

Extranodal low-grade B-cell lymphoma of the MALT type and FCL are the most frequent types of peripheral B-cell neoplasms seen primarily in the skin. [21, 22, 23] Extranodal MZL may develop from reactive infiltrates that represent immune responses to external factors or autoantigens. [24] An etiopathological relationship to B burgdorferi has been demonstrated in some cases. [25, 26]

Clinically, MZL manifests as solitary or multiple reddish, dome-shaped papules, nodules, or erythematous plaques, frequently located on the trunk and extremities and, to a lesser extent, on the head and neck area. [27, 28] (See the image below.)

It is also important to note that secondary cutaneous MZL can have various findings, including a presentation of lipoatrophy. Early detection is crucial as treatment of the primary cause can lead to regression of lymphoma. [29]

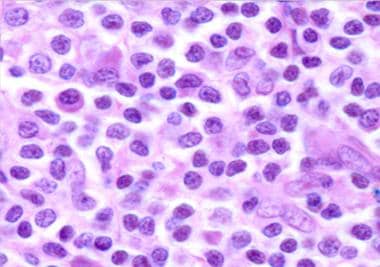

Histologic findings of primary cutaneous MZL include a nodular or diffuse nonepidermotropic infiltrate composed of small to medium-sized lymphoid cells with indented nuclei and abundant, pale cytoplasm (marginal zone cells, monocytoid B-cells) or lymphoplasmacytoid cells. [30] Darker chromatin-rich cells are surrounded by pale-staining cells, resulting in a characteristic inverse pattern. Remnants of reactive germinal centers are present, colonized by tumor cells and reactive T cells. [31] (See the image below.)

The tumor cells express the following immunophenotype: CD19+, CD20+, CD22+, CD43+, CD79a+, CD5-, CD10-, CD23-, bcl-6-, bcl-2+, KiM1p+ (monocytoid B-cell–related antibody). (See the image below.) Plasma cells, often located at the periphery of the infiltrates, show monotypic expression of immunoglobulin light chain kappa more frequently than lambda. Plasmacytoid cells may be present in confluent aggregates. A variable number of reactive CD3+ T cells are present. Clusters of CD123-positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells are present in MZL, but they are found to a lesser extent or are absent in other cutaneous B-cell lymphoma forms. [32]

Molecular analysis has shown that immunoglobulin H (IgH) genes are clonally rearranged in most cases. [33] Translocation of t(11;18), as is seen in the nodal counterpart, is usually not found in primary cutaneous MZL.

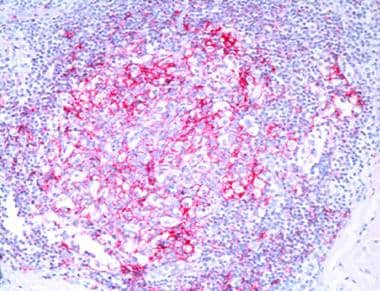

Primary cutaneous MZL with high numbers of monotypic plasma cells and lymphoplasmacytoid cells showing intranuclear periodic acid-Schiff–positive globular inclusions (Dutcher bodies; see the image below) was previously referred to as cutaneous immunocytoma. [25, 34]

Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) is an indolent lymphoma of follicle center cells (predominantly centrocytes with an admixture of centroblasts). The prevalence rate is approximately 12%.

Primary cutaneous FCL has an excellent prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of greater than 90%, [17, 35] and it recurs in up to 40% of patients. Extracutaneous spread occurs very rarely. Primary cutaneous FCL arising at the legs and those cases with expression of FOX-P1 appear to have a worse prognosis and should be treated more aggressively, similar to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), leg type. [18]

Synonyms based on classification are as follows:

-

WHO classification (2008) - Primary cutaneous FCL

-

WHO/EORTC classification (2005) - Primary cutaneous FCL

-

WHO classification (2001) - Cutaneous FCL

-

REAL classification (1997) - FCL, follicular

-

EORTC classification (1997) - Primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma

Reticulohistiocytoma of the back, or Crosti lymphoma, is a variant of cutaneous FCL. [36]

Clinically, nodules and tumors are found most frequently in the head and neck area, but they are also found in other locations of the body (see the image below). [37, 17] A firm consistency without ulceration is very typical.

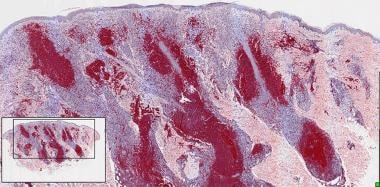

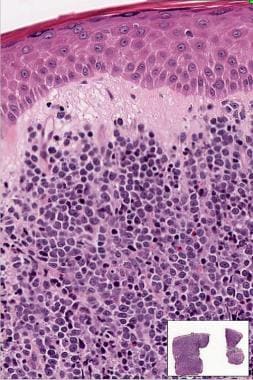

Histologically, 3 growth patterns can be differentiated: follicular, follicular and diffuse, and diffuse. The diffuse pattern is, in fact, the most common seen in primary cutaneous FCL. (See the image below.) The infiltrates are composed mainly of centrocyte-like cells with intermingled centroblasts and immunoblasts. A subepidermal grenz zone is present in most cases. Mitoses, tingible body macrophages, and starry-sky features, typically found in reactive lymph follicles, [38] are rare or absent in FCL.

Immunophenotypically, the cells in FCL express CD19+, CD20+, CD22+, CD43+, CD79a+, CD5-, CD23+/-, CD30+/-, [39] CD43, bcl-6+, and bcl-2-. CD10+ is expressed in cases with a follicular growth pattern. Follicular dendritic cells (CD21+) are arranged in an irregular network (see the image below). The MUM/IRF4 antigen, which is positive in DLBCL, is not expressed in FCL and may be helpful in differentiating FCL with a diffuse growth pattern from DLBCL.

Molecular analysis shows clonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes. In contrast to secondary skin involvement in FCL, chromosomal translocation of t(14;18) and BCL2 gene rearrangement are absent in most cases of primary cutaneous FCL. [40, 41] Although rare, when chromosomal abnormalities do exist, mostly of BCL2 or MALT1, there appears to be no change in prognosis. [42] Studies on gene expression profiles have shown distinct patterns in various types of B-cell lymphoma of the skin. [43, 44]

Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) that accounts for approximately 6% of all cutaneous lymphomas. It is associated with a relatively poor prognosis compared with other primary CBCLs, with a 5-year survival rate of 20-55%, and it tends to spread to lymph nodes and extracutaneous sites. [45, 46, 47]

Two groups of primary cutaneous DLBCL have been differentiated: leg type and DLBCL, other. The leg type usually occurs on the lower legs of elderly women. The term is similar to terms used in the classification of other extranodal lymphomas (eg, nasal type). It manifests with a distinct phenotype and can also be present in other locations of the body, such as face and neck [48] (with a similar poor prognosis).

DLBCL, other includes T-cell/histiocyte-rich DLBCL, plasmablastic lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, and other types that do not fulfill the criteria for a DLBCL, leg type. [49, 50, 51]

Synonyms based on classification are as follows:

-

WHO classification (2008) - Primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type

-

WHO/EORTC classification (2005) - Primary cutaneous DLBCL (including [1] DLBCL, leg type; and [2] DLBCL, other)

-

WHO classification (2001) - DLBCL

-

REAL classification (1997) - DLBCL

-

EORTC classification (1997) - Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma of the leg

Clinically, these lymphomas usually manifest as a solitary nodule or as multiple tumors restricted to one anatomic area (see the image below). They have a strong tendency for extracutaneous spread into regional lymph nodes and other extracutaneous sites.

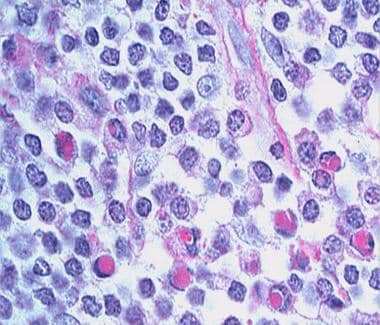

The histological features are characterized by a diffuse infiltrate sparing a thin subepidermal grenz zone in most cases, covering the entire dermis, destroying adnexal structures, and extending into the subcutaneous tissue. The tumor cells are large B cells, formally referred to as centroblasts and immunoblasts. [46] (See the image below.) Centrocytes, which are typically seen in FCL, are minimal or absent in DLBCL.

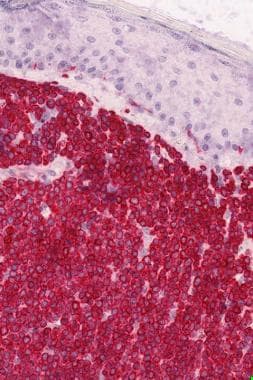

The immunophenotype of the neoplastic cells is CD19+, CD20+, CD22+, CD5-, CD10-, CD79a+, bcl-2++, bcl-6-/+, MUM1+, CD138-, cyclin D1-. The strong positivity for Bcl-2 protein and MUM-1/IRF-4 [52] allows differentiation of FCL with a diffuse growth pattern from DLBCL. (See the image below.) Networks of CD21-positive follicular dendritic cells are not found in DLBCL.

Molecular analysis shows clonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes. In primary cutaneous DLBCL, t(14; 18) and the bcl-2/JH translocation cannot be detected. [53] There is a high prevalence of MYD88 L265P mutation (a leucine to proline mutation at codon 265 [L265P] in the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 gene [MYD88]), which has also been linked to a worse prognosis. [54] Gene expression profiles of DLBCL and FCL with a diffuse growth pattern are different. [43, 44, 55]

Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Variants of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma that are not primarily cutaneous, but rather involve secondary skin involvement, include the following:

-

Mantle cell lymphoma

-

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis

-

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

-

Burkitt lymphoma

Skin involvement in mantle cell lymphoma is rare and usually secondary. [56] Cyclin D1 is a useful marker for the small tumor cells derived from mantle cells, as in mantle cell lymphoma.

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a rare multisystemic, angiocentric, and angiodestructive B-cell lymphoproliferative disease that involves extranodal sites, especially the lungs, skin, and nervous system. It is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and may progress to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Burkitt lymphoma occurs endemically in children in the so-called lymphoma belt of Central Africa and is associated with EBV infection in most cases. Sporadic EBV-negative cases may be seen in association with HIV-induced immunodeficiency. [57]

Waldenström macroglobulinemia is characterized by a clonal expansion of lymphocytes with plasmacytoid features that produce a monoclonal immunoglobulin M protein and infiltrate bone marrow, lymph nodes, and the spleen. Cutaneous involvement usually is nonspecific, showing urticarial and purpuric eruptions, ulcers, bullous lesions, and vasculitis.

Multiple myeloma with monoclonal gammopathy typically induces hyperkeratotic spicules, preferentially on the face. [58]

Differential Diagnosis

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) must be differentiated from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and B-cell pseudolymphoma. In addition, various types of CBCL must be differentiated.

Small cell lymphocytic lymphoma may mimic primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma with colonization of germinal centers. [59]

Differentiation of CBCL from CTCL

The history in CTCL usually involves a prediagnostic-preneoplastic phase over several years, during which differentiation from dermatitis may be challenging or even impossible. In contrast, CBCL lesions evolve quickly, usually within a few weeks.

Most CTCLs show typical clinical features. The prototypical CTCL, mycosis fungoides, starts with eczematous patches, slowly developing into plaques over years or sometimes over decades, and finally—in a subset of patients—evolving into exophytic tumors with ulceration.

The most significant discriminating histological feature between T- and B-cell lymphomas of the skin is the growth pattern, [12, 60, 61] which is horizontal, disklike, and epidermotropic in CTCL and is balllike, spherical, and nonepidermotropic in CBCL. Moreover, infiltrating cells in CTCL tend to be small and irregularly shaped, with convoluted and indented nuclei. Cells in cutaneous B-cell lymphoma usually are oval or roundish, reflecting the shapes of large follicular center cells, immunoblasts, or plasma cells.

The immunophenotypical features are clearly different and correspond to the T- or B-cell lineage from which they originate. Genotyping reveals clonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes and of T-cell receptor genes, respectively.

Differentiation of CBCL and B-cell pseudolymphoma

The most important differential diagnosis of CBCL is from B-cell pseudolymphoma (PSL) (lymphoid hyperplasia) of the skin. [34, 62, 63, 64] Clinically, PSL is usually located as a single nodule on the face, neck, mammillae, or scrotum following B burgdorferi infection through a tick bite, tattooing, or other mechanical or infectious irritants. The nodule of PSL has a soft consistency, whereas the nodules of CBCL are firm or even hard.

Histologically, the infiltrate in CBCL is usually dome shaped with a convex border of infiltrative nodules. In PSL, it is wedge shaped, showing concave borders of the infiltrate. The latter may show regular germinal center formation, as is seen in reactive lymph nodes, with many starry-sky macrophages carrying ingested nuclear dust. Eosinophils, polyclonal plasma cells, and many T cells are present in the periphery and within the follicular area.

Immunophenotypically, the expression presence of both kappa- and lambda-positive cells in the infiltrate argues in favor of PSL. In PSL, the networks of CD21+ dendritic cells are regular, round, or oval; in CBCL they are irregular, ringlike, or bizarre, if present at all.

Genotyping reveals clonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes in most cases of CBCL and lacks clonality in PSL.

Differentiation of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma subtypes

In contrast to primary CTCLs, the various types of CBCLs appear clinically quite similar. However, a few criteria are seen more frequently in one or another type. Nodules and tumors of MZL and of FCL demonstrate a hard consistency. Nodules occur more frequently in the head and neck area in FCL and on the trunk or arms in MZL, whereas single or grouped tumors on the lower legs typically appear in DLBCL, leg type, in elderly patients. [17, 18]

The histological growth pattern is nodular, with convex borders. The infiltrating cells correspond in morphology to their normal counterparts, which are small lymphocytes and large follicle center cells, immunoblasts, and smaller mantle cells or marginal zone monocytoid or plasmacytoid B cells.

The immunophenotypical pattern is most important in the differentiation of various entities of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. The typical differential features are given in the Table below.

Table. Differential Phenotyping of Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma (Open Table in a new window)

|

Bcl-2 |

Bcl-6 |

CD10 |

t(14;18) |

MUM1/IRF4 |

MZL/Immunocytoma |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

FCL |

- |

+ |

+/- |

- |

- |

Secondary FCL |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

DLBCL |

++ |

+ |

- |

-/+ |

+ |

PSL |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

MZL— Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma ; FCL—Follicle center lymphoma; DCBCL—Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; PSL—B-cell pseudolymphoma |

|||||

Gene rearrangement studies are helpful adjunctive diagnostic markers in the differentiation of CBCL from CTCL and B-cell PSL, but they do not allow discrimination of CBCL subtypes.

Gene expression profiles may be helpful for discriminating DLBCL from FCL and other subtypes of CBCL. [43, 44, 55]

Workup of Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma

The diagnosis of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) is established by analysis of skin biopsy specimen, using histomorphology and cytomorphology, immunohistochemistry and phenotypic features, and genotyping and cytogenetic studies. [65, 66]

Histomorphology and cytomorphology

CBCL exhibits a typical growth pattern, referred to as a B-cell pattern. [60] It is characterized by a nodular infiltrate (often well demarcated) of densely packed lymphoid cells in the dermis with convex margins, without significant interstitial infiltration and without epidermotropism. The subepidermal grenz zone is free of lymphoid cells. Whereas inflammatory infiltrates usually comprise a mixture of various cell types, lymphoproliferative disorders, especially FCL (diffuse type) and DLBCL, mostly show a predominance of one cell type.

Cytomorphologically, the infiltrating cells in CBCL correspond to small lymphocytes or to the cellular components of the lymph follicle (ie, centrocytes, centroblasts, mantle cells, monocytoid B cells of the marginal zone, plasma cells, or immunoblasts).

Immunohistochemistry and phenotypic features

Immunohistochemical identification of the tumor cell phenotype plays a crucial role in the diagnostic workup, especially of CBCLs. The most important antibodies for CBCL are CD5 (expressed in B-cell chronic lymphatic leukemia), CD20, CD79a, CD21 (marker for follicular dendritic cells), CD10, Mum-1/IRF4, bcl-2, bcl-6, and kappa- and lambda light chains.

Classic T-cell markers (ie, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD7, CD43 [also stains blastic B cells and a variety of histiocytic cells], CD30) should be negative. However, be aware of aberrant expression of T-cell markers (ie, CD43, CD5) or of CD30 in cutaneous B-cell lymphoma.

Translocation of the BCL2 gene (t14;18), [40] although regularly seen in nodal follicular lymphomas, is usually negative in CBCL. Thus, this cannot be regarded as a helpful diagnostic tool in these cases.

Genotyping and cytogenetic studies in cutaneous B-cell lymphomas

The tumor cells show clonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes in 60-70% of CBCL cases. Cases of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia with monotypic plasma cells have been reported, which have been considered a biologically distinct clinicopathological entity. [64]

The genetic defects in cutaneous lymphoma are heterogeneous. [12] Thus, to date, the detection of chromosomal abnormalities has limited diagnostic or prognostic value in CTCL and CBCL. Nodal follicular lymphoma is determined by the presence of a unique translocation between chromosomes 14 and 18, t(14;18)(q32;q21), BCL2-JH gene rearrangement that is not present in primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL).

Genetic alterations have been detected in intravascular lymphoma. Although these alterations possibly delineate the critical mutations associated with the initiation and progression of this disease, they do not have diagnostic relevance. [67]

Cytogenetic analysis using fluorescence in situ hybridization and other techniques has shown that recurrent chromosomal abnormalities known in systemic marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL) of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type and in nodal FCL rarely occur in primary cutaneous disease of these types. [68] A reciprocal translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 12 and 21, t(12;21)(q13;q22), has been found in a patient with primary cutaneous FCL, [69] which again may suggest a potential pathogenetic pathway of these tumors, but so far has no practical diagnostic relevance.

The modern standard procedure to elucidate and define the normal and pathologic state of a cell or tissue type is the analysis of tissue-specific gene expression and functional profiling by microarray technology. [43, 44]

Blood tests, laboratory tests, and other investigations

In primary CBCL, abnormalities in routine laboratory investigations are not expected. A routine blood cell count is performed in order to exclude leukemic spread to tumor cells, which is unlikely if palpable enlargement of the lymph nodes is absent.

The likelihood of significant node involvement in patients with nonpalpable nodes is low; therefore, blind lymph node biopsy is not indicated. However, a lymph node biopsy should be performed if lymph nodes are enlarged.

Additional investigations include chest radiography, ultrasonography, and CT scanning of the abdomen and peripheral lymph nodes. CT scanning of the abdomen and peripheral lymph nodes is useful in patients with advanced skin disease and palpable lymphadenopathy, to provide an accurate baseline assessment and to document disease progression.

A bone marrow biopsy should be performed in patients with FCL/DLBCL, in order to confirm the primary cutaneous origin and to exclude extracutaneous origin of the lymphoproliferative disorder. It is, however, optional in patients with MZL. [70]

Treatment and Management

Overtreatment in follicle center lymphoma (FCL) and marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL) must be avoided because cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) have a much better prognosis than their nodal counterparts. Aggressive systemic treatment regimens are suitable only for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and for patients with extracutaneous spread. Treatment follows standard regimens for primary nodal lymphomas in these patients, as in B-cell lymphoma.

The treatment of primary cutaneous lymphomas associated with an excellent prognosis (ie, MZL [including immunocytoma] and FCL) [71, 72, 73, 74, 75] depends on whether the patient has a solitary lesion or multiple lesions. [76]

First-line treatments for solitary lesions include surgical excision, antibiotics, and radiotherapy. Antibiotics and radiotherapy, but not surgical excision, are also first-line treatments for multiple lesions.

Antibiotic treatment consists of doxycycline at 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks [77] or pulse therapy with cefotaxime [72, 78] in Borrelia -associated cases. Radiotherapy may include the following:

-

20-100 kV Orthovolt therapy 1-4 times per week, to a total dose of up to 15-20 Gy [79]

-

Extended-field irradiation at 30 Gy (4 fractions of 2.5 Gy/wk)

-

Localized-field irradiation as either a boost after extended-field irradiation or as definitive treatment

Second-line treatments for solitary lesions include the following:

-

Intralesional glucocorticosteroids

Second-line treatments for multiple lesions include the following:

The treatment of primary cutaneous lymphomas associated with a poor prognosis (ie, DLBCL, intravascular lymphoma) [71] is shown below (also see B-Cell Lymphoma).

First-line treatment for isolated or grouped lesions includes the following:

-

Radiotherapy: 20-100 kV Orthovolt therapy 1-4 times per week, to a total dose of up to 15-20 Gy [79] ; extended-field irradiation at 30 Gy (4 fractions of 2.5 Gy/wk); localized-field irradiation as either a boost after extended-field irradiation or as definitive treatment; energies of 45 kV x-ray filtered by 0.55 aluminium for small depth lesions and higher energies (≤100 kV) for deeper lesions; radiation dose varies from 30-40 Gy (fractions of 2 Gy/wk) [23, 80, 81, 82]

-

Surgical excisions

First-line therapies for multiple lesions include the following:

-

Polychemotherapy: CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin [vincristine], and prednisone) regimen

Second-line therapy for multiple lesions is polychemotherapy (as above) plus rituximab.

Follow-up

Patients should be seen in an outpatient setting at least every 6 months for a clinical workup. They do not require any additional laboratory workup unless enlargement of the regional lymph nodes has occurred.

Questions & Answers

Overview

What is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL)?

What is the pathophysiology of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL)?

What is the prevalence of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL)?

How is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) classified?

What is marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL)?

Which physical findings are characteristic of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL)?

Which histologic findings are characteristic of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL)?

Which immunophenotype are expressed by marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL)?

Which molecular analysis findings are characteristic of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL)?

What is primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL)?

What are synonyms of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL)?

Which physical findings are characteristic of follicle center lymphoma (FCL)?

What are the distinct histologic growth patterns of follicle center lymphoma (FCL)?

Which immunophenotype are expressed by follicle center lymphoma (FCL)?

Which molecular analysis findings are characteristic of follicle center lymphoma (FCL)?

What is primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)?

What are synonyms of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)?

Which immunophenotype are expressed by primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)?

Which molecular analysis findings are characteristic of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MZL)?

What are the variants of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with secondary skin involvement?

Which conditions are included in the differential diagnoses of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma?

How is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) differentiated from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)?

How is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) differentiated from B-cell pseudolymphoma (PSL)?

How are the cutaneous B-cell lymphoma subtypes differentiated?

How is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) diagnosed?

What is the role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL)?

What is the role of lab tests in the workup of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL)?

What are the first-line treatments for FCL and MZL?

What are the second-line treatments for FCL and MZL with a solitary lesion?

What are the second-line treatments for FCL and MZL with multiple lesions?

How are DLBCL and intravascular lymphoma with isolated or grouped lesions treated?

How are DLBCL and intravascular lymphoma with multiple lesions treated?

What is included in the long-term monitoring of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL)?

-

Solitary nodule in marginal zone lymphoma.

-

Monocytoid B cells and plasmacytoid cells in marginal zone lymphoma.

-

Marginal zone lymphoma, CD20.

-

Intranuclear periodic acid-Schiff–positive Dutcher bodies in immunocytoma (marginal zone lymphoma).

-

Follicle center lymphoma. Multiple skin tumors.

-

Small and large follicle center cells.

-

Follicle center cell lymphoma. Irregular pattern of CD21-positive dendritic cells.

-

Tumorous lesions on the legs in a patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

-

Large lymphoid cells of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, sparing a subepidermal grenz zone.

-

Neoplastic cells in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with strong positivity for bcl-2.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology

- Classification

- Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma (MALT-Type)

- Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

- Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

- Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma

- Differential Diagnosis

- Workup of Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma

- Treatment and Management

- Questions & Answers

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- Tables

- References