Bill Henson: ‘There is no formula for how creativity unfolds’

Bill Henson is one of Australia’s best-known contemporary photographers – but it was not always thus. As the First Commissions art project launches ahead of an exhibition in Melbourne on 27 and 28 July, he tells Mireille Stahle about his early years as an artist.

Every artist’s career, approach and aesthetic is different – as can be seen in the 30 responses by emerging artists to the First Commissions project. As a photographer, my approach will never be the same as a theatre maker. That said, there are two key attributes that all artists should aspire to. I’ll discuss those below, but first, a bit about my own journey.

I grew up in Melbourne during the 50s and 60s. I grew up in the outer suburbs in a semi-rural setting. I spent a lot of time wandering around, daydreaming, looking at the clouds – the beauty of the world around me. What can I say about how “occupied” I was? I painted and drew compulsively. My mother told me I used to cover square miles of butcher’s paper. I was fascinated by everything to do with pictures and I was always busy making things. Whether I was trying to draw a gum tree down the road, or trying to make clay bricks to build an Egyptian temple.

I don’t think that my passion for making ever changed. And really, I don’t ever recall thinking to myself in any extended way “what am I going to do? What do I want to do? What will I study?” or, “what am I going to do with my life”. I never had those kinds of thoughts as I was just always busy trying to make something.

I’ve always felt a little on the outside of this business of “careers” and “professions” and so forth. I remember giving the VCA graduation address at Hamer Hall one year – they wanted me to talk about “professionalism” but I had to be honest and say that I’d always felt like an amateur; an amateur in the eighteenth century sense of the word – somebody doing something for the love of it.

Indeed art has never felt like a profession to me. And, of course, because I’ve had the fortunate accident of having a lot of interest in what I’ve made over the years, I’ve never really had to work for other people. I’ve been my only “client” if you like. I’m sure this reinforced a feeling of not really being “employed”.

The great and terrifying thing about being “one’s only client” is that you have complete freedom, but you also have total responsibility. One can’t defer to a panel of experts: “yes dear, don’t worry, that looks fine”. There is a sense of isolation or insulation from the world that occurs when you work alone. Composition is a very different headspace to performance. I spend most of my time in the studio staring at a picture, and asking myself “what’s wrong with this?” Trying to resolve things in a picture, for me, ultimately comes down to aesthetics – and it’s children who ask the best questions about such matters: “how do you find the right size? How do you know when a picture is finished?” The definition I came up with for that one was; “Well, it’s finished when it remains interesting and there’s nothing more I can do to it.”

Ultimately, with art, it is the same for an audience as it is for the artist in that the viewer has also to go on their own journey. The simple fact is that there is no “correct” way of looking at Rembrandt, there is no “correct” way of listening to Mozart, there’s only your way. This is one of art’s great gifts to society – it sends us back into ourselves reinforcing the priority of individual experience.

Art should be as democratic as possible in terms of accessibility for the community. But the creation of great pieces of music or great works of sculpture, or whatever has to be acknowledged as something that few people can achieve. I believe in vertical hierarchies. Not everyone can do what some people can do, and the way that I explain that is to say: “Look, there are tens of thousands of people in the world who can play the piano very, very well. But there are only a handful who can play the piano, and make you feel like you’re in a thunderstorm”.

I like a comment in Elias Canetti’s daybooks about this: “virtuosity – the last refuge of art!” This is kind of brutal, but essentially it is about honesty. We have a responsibility to speak the truth as we see it. It helps everyone find the truth of their own lives, and it helps people sort out what they really want, or should I say, need to do, rather like taking a long hard look in the mirror. Err, but then again in the age of the selfie, perhaps the mirror is no longer such a good idea …

We’ve all heard twenty versions of Mahler’s ninth symphony but the very best of them affect us as if it were a new piece of music. The score doesn’t change – but an especially gifted conductor will reimagine the work in a way that opens up whole new spaces that one has never heard in the music before.

Making a picture, of course, can be the same – it can suggest so much. Once again, it’s how the work opens up spaces for the imagination and for the maker, when work is going really well and the picture is absorbing, even compelling, they can feel almost invincible – for a moment. On the other hand, when something is not working, one can feel like a complete fool and as if it’s “all my fault”. To me it seems that when a picture is really working, it feels as if the picture is making itself and I’m just along for the ride.

There is no formula for how creativity unfolds and whatever forms are articulated during the process. There is no “correct” way of making things just as there isn’t, as I said before, a “correct” way of looking at an artwork. The only advice I give students consists of two parts and we need both. Try to be true to yourself, and don’t stop working. That’s it. These are the twin peaks of Kilimanjaro – if you want it in Monty Python’s terms.

We need to try to build a bridge between those two peaks and, of course, ultimately what you’re after is the impossible. If you think about history and realise how incredible some works are – this “thing” that someone has made and then stop and think about its journey from the world of imagination into the physical world, it is breathtaking. The trajectory is entirely unreasonable and its often experienced as what I call a “gradual shock”. It has an affect that can take decades to unfold in one’s life and it feels, always, “against the odds”.

Part of what’s so incredible is the unlikeliness of its conception. When people stand in front of Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal in Saint Petersburg for example, chattering to each other, they often forget what they’re saying and fall silent (I watched this happen for a week) and it’s because of the power of the object. It’s the unlikeliness of someone managing to bring this thing into the world. The paint seems like the physical manifestation of pathos – is the physical manifestation of pathos. It’s staggering in its “against-the-odds-ness” to such a degree that one feels acutely that it might just as easily not have come into existence. This whole apprehension of an artwork being “just inside the physical world” is a cardinal quality of the greatest art.

First Commissions

We hope that First Commissions will be a moment in which these young artists might experience a creative epiphany. As an artist you have these events that occur from time to time in your life and one thing they do is make you aware of the fact that there are people who are interested in what you’re doing. “This is disgusting! You should be arrested!” Or “Oh no, we love these pictures!” Whatever you do you’re never entirely isolated from public opinion, we’re all a product of our time and place and so one always encounters other people’s thoughts and feelings about the work, however, I do think an institutional setting is always an excellent place to rattle the cage.

Regardless of the specific output, the most important thing is the opportunity a student gains to meet interesting people – and particularly people not doing the same thing you’re doing. I’m not a film director but I think there’d be a lot to be gained from meeting a Scorsese or perhaps an astrophysicist or an incredible communicator such as neuroscientist Susan Greenfield.

This cross-fertilisation is very important, and something that has always happened at the VCA. I remember John Walker who was dean of the school of art back in the ’80s. He made a particular point of inviting all kinds of people to visit the school. There were people coming to speak to the students all the time; people who ran oil companies, people who flew jets, it was endless.

Regarding commissions, I can say the most interesting thing about the few that I’ve accepted over the years, is still the “conversational aspect” in the work as evidence of a journey you’ve undertaken into perhaps less familiar waters. When you have a conversation that bridges disciplines, things do come to you in unexpected ways.

Richard Tognetti from the ACO came to see me years ago – 2004 I think it was – and said, “You know, we’d love to collaborate with you. We have no idea what form it might take but what do you think?”

I said, “Well, I have no idea either – lets see”.

In those early conversations all we did was play Haydn symphonies to each other. We’d get together and just listen to music. About a year went by before it “clicked” for me. I was thinking about how I might give a still object, in my case a photograph, a more dynamic presence on stage? Objects gain much of their power from their stillness and silence. Indeed these are the two things one needs for contemplation. Suddenly, or so it seemed, after rolling it around in the back of my mind for a year or so – I realised what I needed to do was film my photographs. Once the penny dropped it, was done.

The orchestra were sending me sound tapes from their rehearsals and I would play them on my stereo in the studio while filming with a movie camera on a big fluid head tripod in front of my photographs but recording not just my pans and tilts across the photographs but also the music in the background – and – my voice-overs explaining what I was doing. But this was just my approach … the next person would have an entirely different idea.

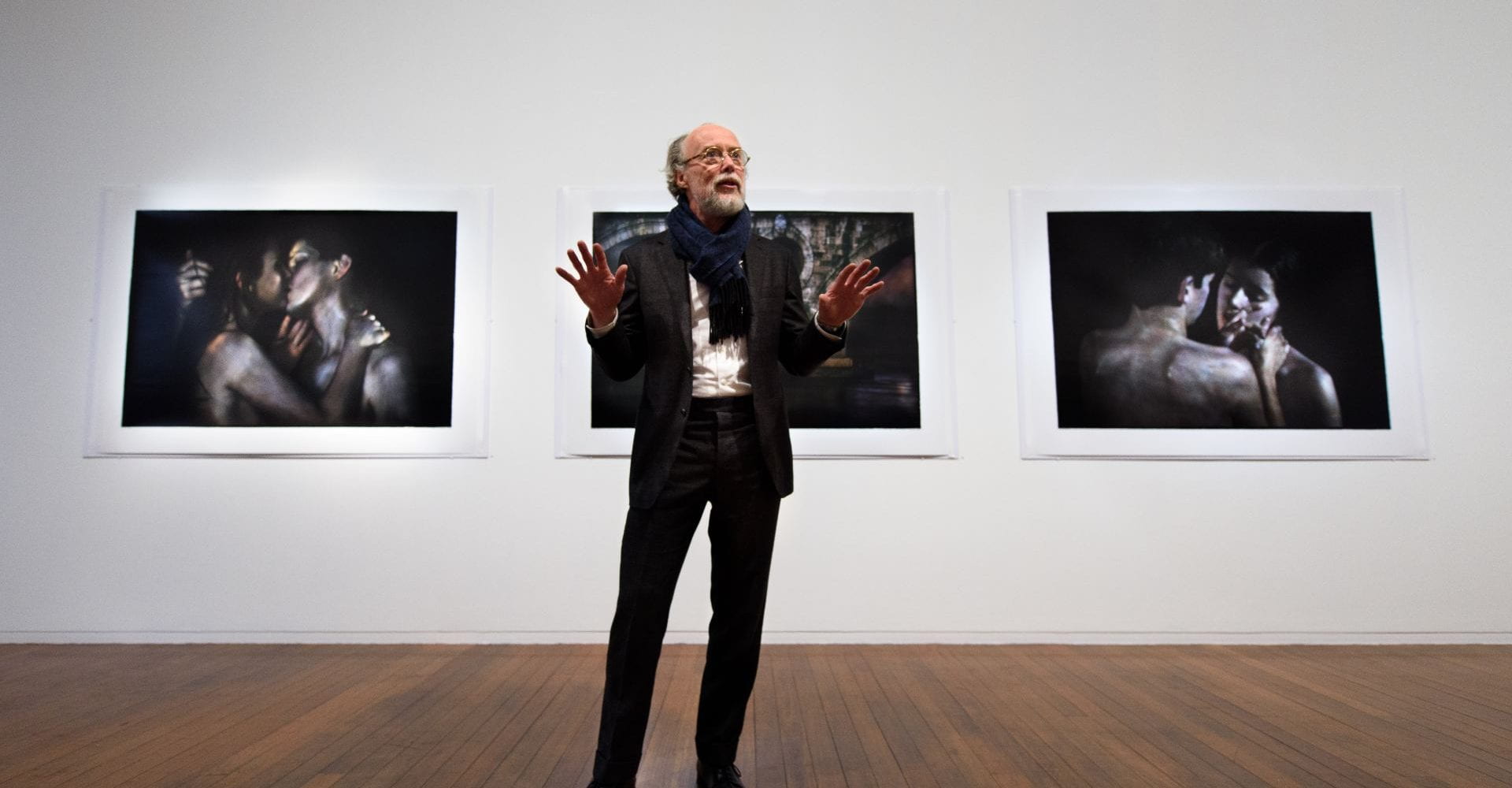

Banner image: Bill Henson by Luis Power. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

An exhibition of all 30 artists’ works for First Commissions will be held at the Martyn Myer Arena, on the University of Melbourne’s Southbank Campus, on 27 and 28 July 2019.