- Fresh Balga (Xanthorhoea preissii) resin Photo: Courtesy the artist

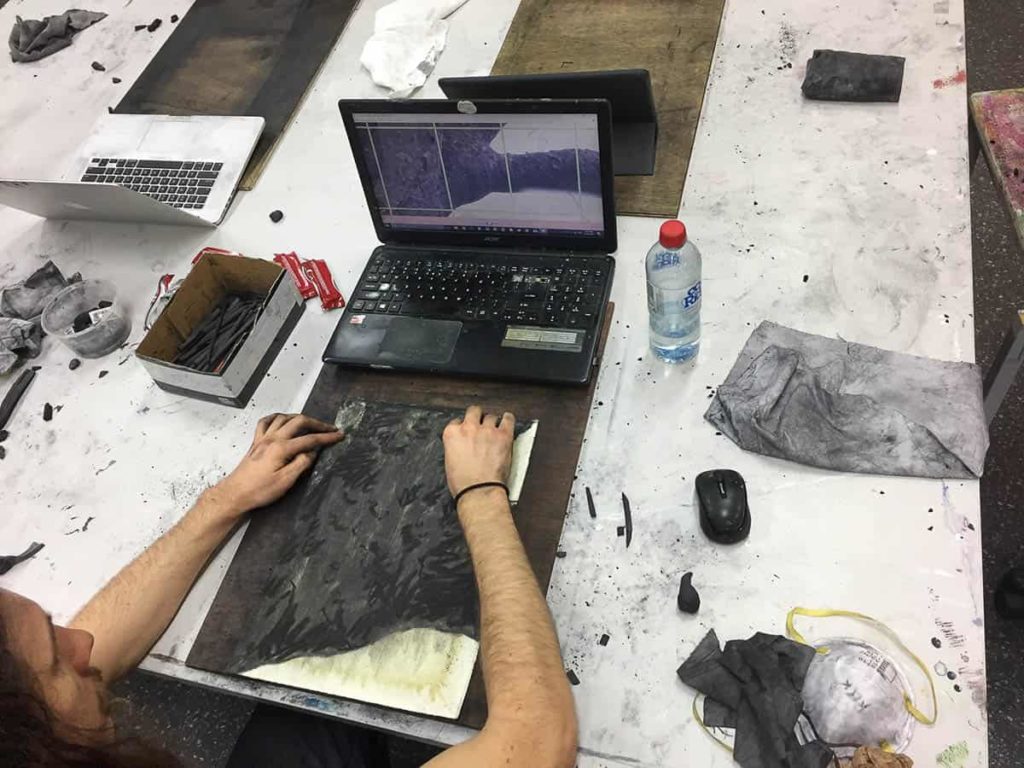

- Studio assistant Ryck Rudd working on Looking Glass, August 2017 Image: courtesy the artist

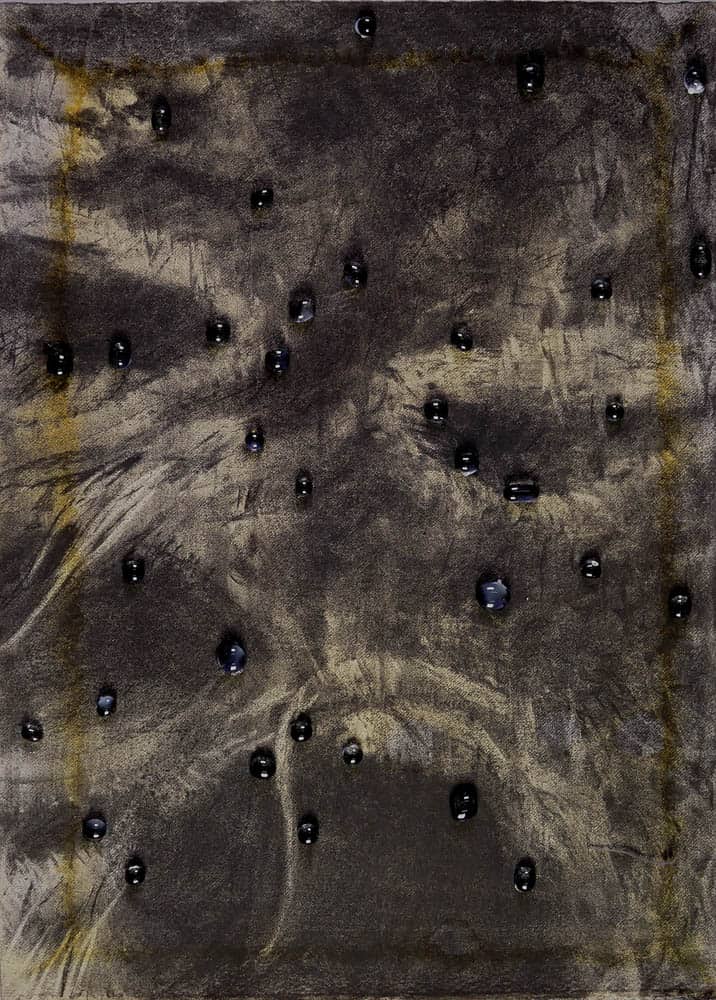

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017 Medium: watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper Dimensions: 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

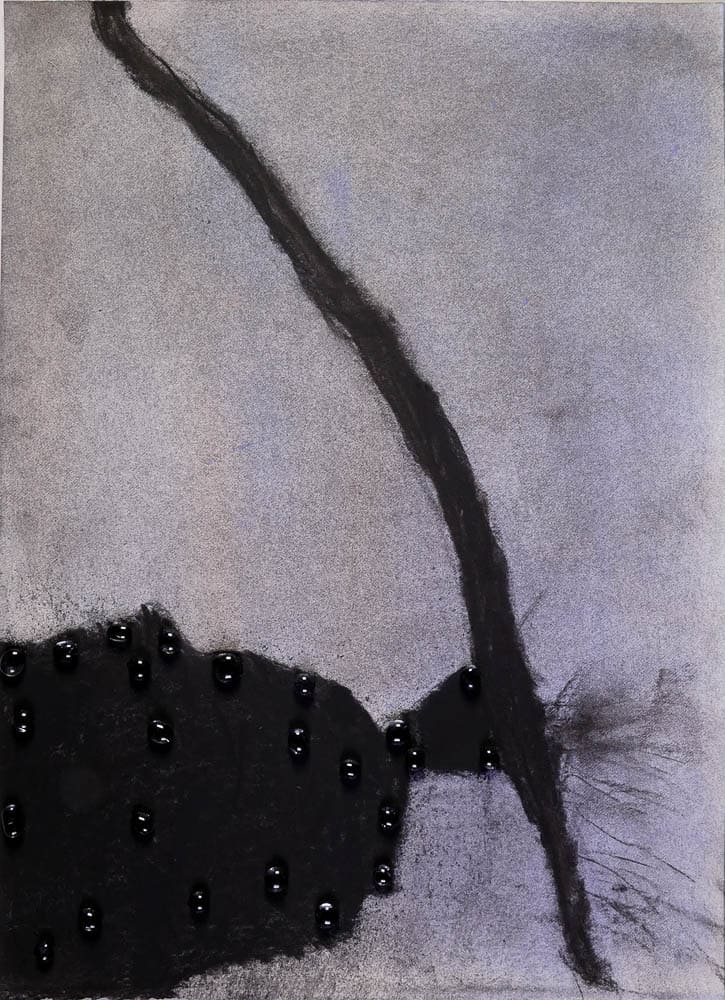

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

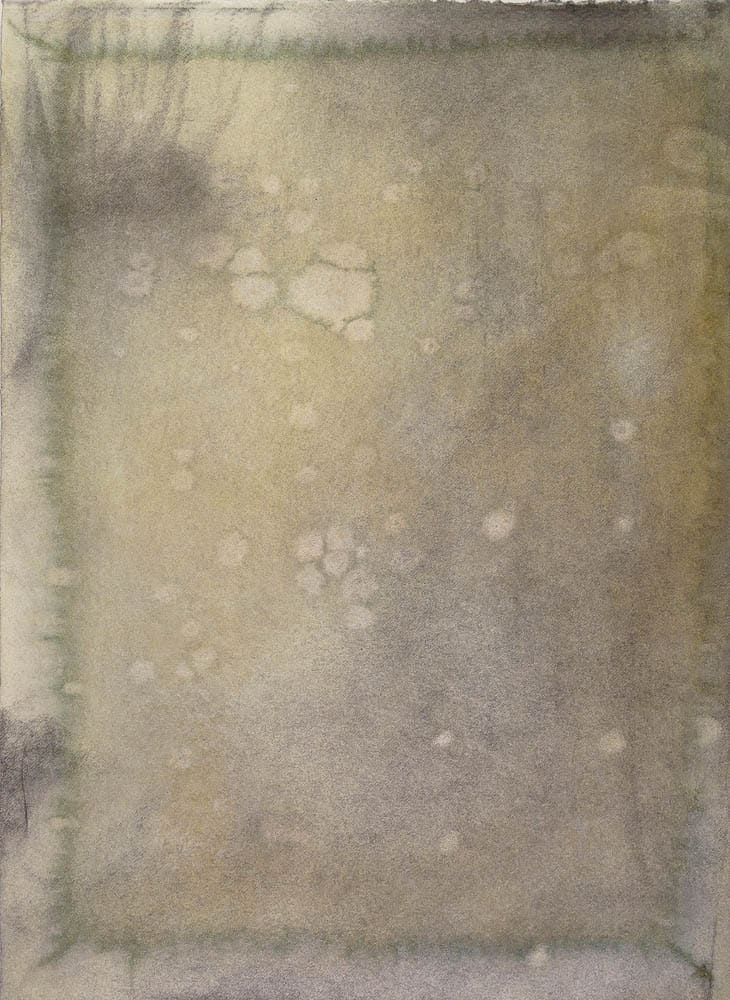

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper Dimensions: 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

In October of 2016, I undertook a field trip through sections of the Yilgarn Craton in Western Australia, in search of damaged lands. This took me to Bungalbin (or the Helena and Aurora ranges), an area of banded ironstone formation that has been under threat from mining, and the Truslove Townsite Nature Reserve, which sits about 80 kilometres north of Esperance. This nature reserve was incinerated in a massive fire that swept through in November 2015, and I was keen to observe not only the blackened bush, but also the first signs of regrowth after the winter/spring rains.

My interest in observing landscape damage and restoration in the field had been prompted by the opportunity to make an immersive, large-scale work for the WA Now program at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. I had also been looking for an opportunity to explore ideas about restoration that linked in with Cesare Brandi’s Theory of Restoration. Brandi was appointed head of the restoration effort in Italy after the extensive damage done to artworks and monuments during the Second World War. Brandi implemented a new theory of restoration that challenged the long-prevailing approach of restoration that endeavoured to replace the missing or damaged areas with work that imitated the original artists work as closely as possible, thereby exorcising any reference to damage and allowing the viewer to appreciate the work as if it had just been made. In effect, this is a restoration approach that aimed to recreate the idea of an “untouched wilderness” in nature.

Brandi felt that damage (whether man-made or natural ) to artworks should somehow be acknowledged in the restoration, and that this damage or loss had in effect, become a part of the work itself. To this end, he worked with the artist restorer couple Paolo and Laura Mora to formulate a technique called tratteggio, which was a method of painting infill made up of a matrix of thin vertical lines that abstracted the lost compositional elements. This method allowed the eye to pass over the artwork in an uninterrupted fashion, but did not endeavour to deceive the viewer into thinking that the work was whole and had been preserved intact since it’s initial execution.

With tratteggio in mind then, I wondered if I could also develop some sort of infill or restoration to a damaged landscape in my practice as a contemporary artist?

The burnt landscape of the Truslove Nature Reserve provided me with a substantial template upon which to build my work, but there was still much missing, and I couldn’t really grasp this until I had returned to the studio. I began to think of the velvety, absorbent blackness of the bush after fire, and remembered that in certain light, the sheen of carbon is activated, thereby introducing a reflective element emanating from the blackened forms. If a black and mute porosity was the epitome of loss and destruction, then I felt there was conceptual scope to put forward reflective, shiny and non-porous materials as more positive harbingers of hope and renewal in nature.

Taking this material cue, I began to investigate the presence of shine, gleam and reflection in the Australian landscape. The first thing to come to mind was the presence of glass in the bush, and in particular, the proliferation of broken amber glass from beer bottles. This distinctive glass weathers to eventually assume mosaic-like qualities, with each fragment being shaped by terrain that has the capacity to elegantly sandblast form, diffusing shine and reflection to allow a more modest glow to emanate from within the fragment.

These fragments of glass found on road verges and at abandoned campsites represent a form of post-colonial midden and it is not surprising that Aboriginal Australians were attracted to this foreign glass as a possible tool and the recent discovery of a beautifully knapped green glass arrowhead found on Rottnest Island, off the coast of Perth is a fine example of material transformation and repurposing.

It is not only humans who have been attracted to the presence of glass in these lands, as the males of a species of jewel beetle found in parts of WA are also attracted to amber glass because of the surface reflection imitating the shine of the female jewel beetles. There is a tragic parallel here, with the introduction of bottled grog creating much damage for the healthy reproduction of those with most connection to the land.

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

- Gregory Pryor, Looking Glass (detail), 2017, watercolour, charcoal, Balga resin (Xanthorrhoea preissii) and glass on paper, 1585 sheets, each measuring 38.2 x 28cm, overall dimensions variable Photo: courtesy the artist

The conceptual resonance of shiny elements in the landscape had now expanded in my thinking to assume more sinister and destructive characteristics. In first contact exchanges, I also realised that Europeans usually exchanged shiny bling in the form of glass beads, brass buttons, fish hooks, mirrors and steel axe heads for the more naturally porous and matte objects made from wood and animal parts provided by the First Australians. The introduction of these shiny objects onto the Australian landmass could therefore be said to be extremely significant for the way they corrupted the behaviour of the existing light.

This Janus-like quality of glass knit conveniently with the methodology of making Looking Glass. Digital images taken at the Truslove Nature Reserve site provided a reflective template for drawing, and the application of a mimetic approach echoed the characteristics of many of these introduced trinkets. Referring to the digital images that had been gridded up to correspond to each of the 1585 sheets of paper that made up the work, I worked with a team of student assistants to quickly draw in the forms with charcoal, then use a cloth to wipe rub back the image and work further with what remained. This method also echoed the man-made or natural process of erasure and restoration that occurs in the landscape.

Despite my excitement at some of these associations, there was some hesitation about working with glass, as I did not want to use it in a manner that was cosmetically decorative. I wanted to reinforce the haptic and gestural quality of applying the charcoal and then manipulating it through smearing, wiping and rubbing actions. The introduction of glass needed to be done with a similar intent and engagement and this is when Brandi’s technique of tratteggio emerged as a useful model. In effect, I wanted to draw with the glass and to introduce it as an element that alluded to loss. I had already begun to incorporate thin, vertical lines with charcoal throughout the work, in a nod to tratteggio and impressed it upon my assistants that every mark they added to the work represented something that had been lost.

To be able to draw with glass, I realised I would need to make a lot of small beads, and after hand cutting around 30,000 tiny pieces, they were fired in a kiln to form tiny droplets with a flat back, which allowed them to be glued onto the sheets of paper. After doing tests with clear and white glass, I remembered a stash of smoke coloured glass I had kept in the studio for many years, realizing it would fit perfectly into the palette of the work—both visually and conceptually.

These droplets of smoky glass connected with the observations gleaned from the site of the Truslove Nature Reserve. Long understood by the First Australians with their well-developed practice of fire stick farming, it wasn’t until 2004 that new Australians discovered a critical component of smoke that many native plants needed to regenerate and stimulate germination. The discovery of the butenolide 3-methyl-2Hfuro[2,3-c]pyran-2-one, by a team of researchers based at King’s Park in Perth, Western Australia was a major breakthrough in our understanding of how Australian plants have been able to survive and prosper for millennia in a harsh climate with nutrient deficient soils. Through this discovery, scientists were also able to synthesize the chemical and make it available to the horticultural industry, where it is now manufactured as an essential ingredient to add to water when propagating many native species.

The final component of the material language that makes up Looking Glass is the resin extruded by the balga (grass tree or Xanthorhoea preissii) here in Western Australia. This resin has a long history of use: as an important ingredient (along with kangaroo scats) of the glue used in spear making by the First Australians and also by various furniture makers and artists since the colonial period. These resin balls provided a naturally occurring form that shared much with the smoky glass beads I had made. The scale was similar, and both were hard, non-porous and transparent. The key difference was that the Balga resin balls were often found covered in a reddish-orange powder, much like cocoa powder that chocolate truffles are rolled in. The fresh resin soon forms a powder coating that eliminates shine like the sandblasted fragments of glass that have been diffused by exposure to the elements.

Our reliance on hard, non-porous materials that carry such diverse characteristics as reflection, mimesis, seduction, survival, industry, permanence and wealth came to the fore as we travelled along a remote dirt track near Bungalbin. One of our vehicles broke down and after inspection, it was discovered that an important steel hex nut had fallen off the underneath of the engine. One of our party decided to walk back along the ill-defined track whilst more inventive repairs were being considered, and to our disbelief, she returned an hour later, with the lost hex nut. It was the light reflected off the hard, reflective surface of the nut that caught her eye in the morning sun, making it stand out from the dusty, dull uniformity of the dirt track. Herein lies the vocabulary that makes up Looking Glass. Its material language spreads across a spectrum of lustre to identify the agents of loss and subsequent renewal that are at the heart of the old country.

Looking Glass was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Western Australia from September 1 2017 to January 15 2018.

Further reading

The Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) has a page on its website that includes an online catalogue for Looking Glass and an essay by Ann Schilo. There are also links to two videos, The Yilgarn Chronicles by filmmaker George Karpathakis which features footage from the fieldwork undertaken, and another film produced through AGWA that focuses on the work being developed in the studio.

For more on the work of Cesare Brandi and the technique of tratteggio, see D. Graham Burnett’s article in Cabinet, #40.

Author

Gregory Pryor is an artist, writer and academic based in Perth, Western Australia. His practice is very project centred and has often been informed by the stimulus of travel and seeing new places through foreign eyes. Pryor arrived in Western Australia in 2003 and since then there has been a strong emphasis on place and the role that botanical diversity and loss plays in shaping the landscape – particularly the ancient landscapes of the South West of Western Australia. His work is featured in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, The National Gallery of Victoria, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, The Queensland Art Gallery and numerous important corporate and private collections. Pryor is represented by Lister Gallery, Perth and he currently works as a lecturer in visual art at Edith Cowan University.

Gregory Pryor is an artist, writer and academic based in Perth, Western Australia. His practice is very project centred and has often been informed by the stimulus of travel and seeing new places through foreign eyes. Pryor arrived in Western Australia in 2003 and since then there has been a strong emphasis on place and the role that botanical diversity and loss plays in shaping the landscape – particularly the ancient landscapes of the South West of Western Australia. His work is featured in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, The National Gallery of Victoria, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, The Queensland Art Gallery and numerous important corporate and private collections. Pryor is represented by Lister Gallery, Perth and he currently works as a lecturer in visual art at Edith Cowan University.