Rococo Beauty Tips

by Kendra Van Cleave, First published for the November/December 2009 issue of Finery

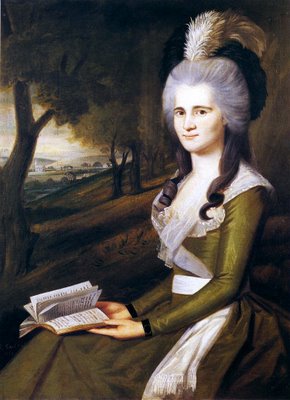

Coiffures of the 18th century defined the style of the era. Women’s hair was always curled, waved, or frizzed before styling. When higher hairstyles came into fashion, they were accomplished by raising hair over pads made of wool, tow, hemp, or cut hair. Throughout the century, hair was styled with combs, curling irons, and pins, and dressed with pomade.

Henry IV of France (1589-1610) began the practice of powdering to disguise his greying hair; Louis XIV (1643-1715) introduced the archetypical white hair powder. Louis XIII (1610-43), who went bald at age 23, started the fashion for wearing wigs.

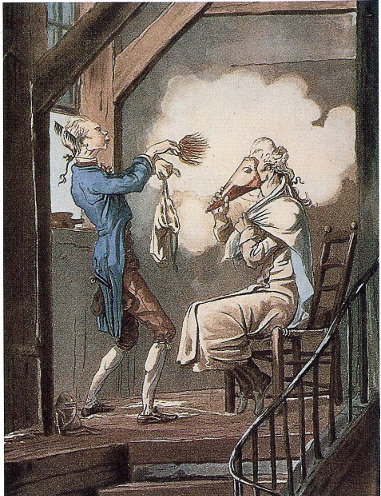

Powder was made from numerous materials, from pedestrian corn and wheat flour to luxurious finely milled and sieved starch. Powder was usually white, but could also be brown, grey, orange, pink, red, blue, or violet. Powder was applied with a bellows (the recipient being covered with a cone shaped mask and fabric smock), with a puff for touchups and a knife for removal. From what can be seen in period portraiture, powder was de rigeur for Frenchwomen. However, English and American women avoided the trend until the 1780s.

In the 1750s, the front hair was waved or softly curled and pulled back simply and close to the head, with only an inch or so of height. Hair was arranged at the back of the head in curls, a twist, or a braid pinned to the head. For evening wear, one or two curls hanging over the shoulder was fashionable.

Ornaments included a few small ribbons, pearls, jewels, flowers, or decorative pins styled together and called a pompom (named for Mme de Pompadour).

In the latter half of the 1760s, women’s hair grew higher (generally equal to about ¼ to ½ the length of the head), often styled in an egg shape. Again, loose hanging curls were minimal and generally worn for evening.

In the 1770s, huge wigs were all the rage. The term “pouf” referred to both the wig itself as well as its accessories (ships, birdcages, stars, ribbons, flowers, feathers, pearls, jewels – you name it, the more the merrier!). The pouf was often styled into allegories of current events, such as à l’inoculation (vaccine), ballon (Montgolfier balloon experiments); or concepts, such as à la Zodiaque, à la frivolité, des migraines, etc.

The wig’s height was generally equal to about 1x to 1½x the height of the head, usually in a hot air balloon shape, and can either stand straight up from the forehead or lean back towards the crown of the head. Side curls were placed on diagonal angles pointing towards the crown. The back hair was styled in curls, often with a small ponytail coming from the base of the head and looped up (either straight, braided, or twisted). A few long ringlets would hang down the neck.

In the 1780s, the forces of the Enlightenment affected women’s hairstyles in favor of what was considered a more naturalistic style. Many women began to forego wigs, wearing their own hair in the hérisson (hedgehog) style.

Women cut their hair shorter (between chin- and shoulder-length), and styled it in a large curly or frizzy halo around the head, with the emphasis on width rather than height. The small ponytail remained, and could be left hanging (straight or in curls), or looped up (again straight, braided, or twisted).

Ornaments became fewer and simpler, generally a ribbon, feather, flowers, or jewel. Powdering began to decline in this decade, although it was still fashionable enough that in 1795 England taxed it to raise money for the war against the French.

From the 17th century, both men and women in England and France had worn obvious cosmetics. Gender differences were less important than class – cosmetics marked you as aristocratic and fashionable, as well as those who were trying to rise in social status.

Makeup was not intended to look natural – in fact, it was usually called “paint” — but instead to proclaim that one was aristocratic through a consciously artificial look. Cosmetics also had practical aims – their use created what was considered an attractive face, and they could hide the effects of age or blemishes.

In France, nearly all aristocratic women wore cosmetics (Louis XV’s dowdy queen Marie Leszcynska was one of the few who did not). In fact, the painting of the face was a key part of the public toilette, an informal ceremony where an aristocratic woman dressed her face and hair before an elect audience. In addition, any bourgeois woman with aims of being à la mode would have worn cosmetics, although perhaps not as heavily.

By 1781, Frenchwomen used about two million pots of rouge a year. Englishwomen were less likely to wear obvious cosmetics than Frenchwomen in the 1750s-60s (in other words, they were wearing cosmetics but with a more natural look) – but by the 1770s-80s, Englishwomen and Frenchwomen wore nearly identical amounts of cosmetics.

The most popular white makeups used on the face were made of lead, which was popular for its opacity despite knowledge of lead poisoning. Red makeups were made of vermilion (ground from cinnabar and including mercury) or creuse (made by exposing lead plates to the vapor of vinegar); both are toxic.

The key aspects of the 18th century cosmetic look are a complexion somewhere between white and pale, red cheeks in a large circular shape (particularly for French court wear) or upside down triangle, and red lips. White or pale makeup can be applied to the neck, chest, and arms. Eyes are usually left bare or have a reddish color around them (underneath and on the lid). Eyebrows are half moons with tapered ends, and can be darkened. Beauty patches (made of velvet, satin, or taffeta) can be part of a more formal look.

The best resource for understanding women’s hairstyles and makeup of this era is period portraiture. There are a number of online resources — my favorite is the Web Gallery of Art (http://www.wga.hu/). For inspiration on DVD, “The Duchess” (2008) has outstanding 1760s-80s hairstyles, and “Jefferson in Paris” (1995) has both 1780s hairstyles plus fantastic period makeup looks.

Leave a comment