Marlon Brando in Streetcar: The Role That Changed Cinema

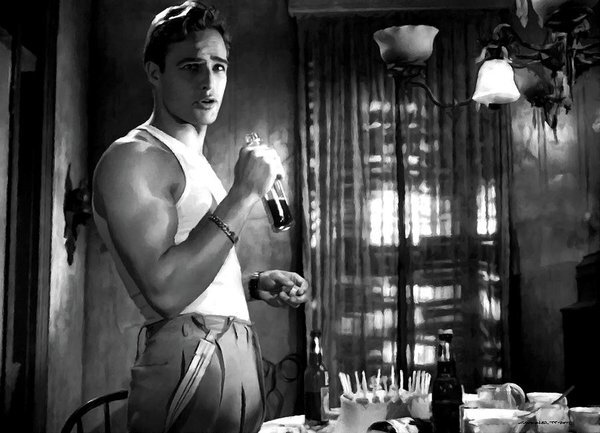

A Streetcar Named Desire. Image courtesy of Warner Bros.

Back in 2006 I was finishing my final year at UCLA, and I took a course in 20th Century American Drama. It was here that I first learned of the work of Thomas “Tennessee” Williams, one of mid-century America’s greatest playwrights. His plays are often shot through with this deep melancholy that you can feel in your bones, a hallmark of 1950s and 60s American drama because I guess if you weren’t a depressed alcoholic swimming in your own sadness than you were nothing at all to the literati.

A Streetcar Named Desire is, of course, one of these depressing dramas although it’s not as full of existential dread as The Iceman Cometh or Long Day’s Journey Into Night. When it comes to penning world-historical depressive fever dreams, Eugene O’Neill was in a class all by himself. Streetcar tells the story of Blanche DuBois, a woman experiencing a mental and emotional breakdown who is basically victimized by society at large but also, in a far more specific way, by her brute of a brother-in-law, Stanley Kowalski played by Marlon Brando.

The play premiered on Broadway in 1947 and it was a hit, launching Brando to stardom. The film adaptation followed a few years later, with the original Broadway cast intact except for the addition of Vivien Leigh as Blanche for some added star power. It was a raw drama about the working class that went for realistic emotions and sought to portray the ugliness and meanness of life and while this might not have been that radical in the theater in the late 1940s (see: Eugene O’Neill) it wasn’t that common for a major Hollywood film in 1951 to feature a lead actor who sexually assaults his own sister in law. So the subject matter, particularly for a film, was pretty provocative for the time.

But the real place in which Streetcar broke ground was the acting. Prior to 1951, almost all actors were movie stars - Carey Grant, Humphrey Bogart. They weren’t particularly great actors - they were stars, carrying films with their big screen charisma. But they couldn’t internalize deep human feeling and convey that through subtle acting and emotional cues. Brando could. When I first read Streetcar for that class at UCLA, like most plays when you read them on the page, it leaves you a bit cold. Dramas are almost always sterile on the page. It takes casting and acting and staging and lighting and the acid energy of live performance to bring everything together.

So I dutifully got a copy of the film and watched it one night, which is the next best thing Marlon Brando being dead and all. I was blown away. It was the type of moment in cinema that I live for, where the experience opened my mind to something I was completely unaware of before. Marlon Brando in Streetcar Named Desire is electric. He moves with this animal magnetism and charisma, this power that is indescribable. You cannot take your eyes off of him when he is on the screen. The “Stella” scene is of course the most famous, but it’s actually the subtleties embodied in his acting that sucked me in. This performance is a force of nature. Stanley Kowalski is meant to be part man but also part beast, and somehow in the way Brando spoke and moved and carried himself the full meaning of that in all of its complexity was carried through the screen.

This performance changed cinema. I’m sure a film historian more pedantic than me can point to other influential Method actors who came before Brando, but in my mind things changed there in 1951. Brando should have won the Oscar that year, unquestionably, as Streetcar is a better and more influential film than On the Waterfront for which he would get an Oscar in 1954. Brando’s style of naturalistic acting was so different from what typified Hollywood acting in the pre-Streetcar era, and it influenced other milestone performances later in the decade, like James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause.

There were essentially two eras in Old Hollywood - before Streetcar and after. I don’t see how a movie audience could watch Marlon Brando turn in that performance as Stanley Kowalski and then go back to watching Bogart flicks without being changed in some way and understanding that what you were watching were two fundamentally different types of performance. After that, cinema would never be the same again.