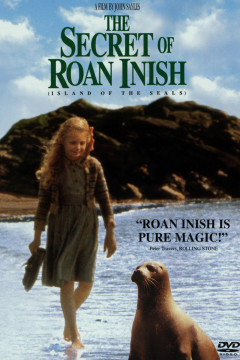

Any day is a good day when I can indulge in a film or a folktale. I count myself rather lucky, then, to be taking a course on both. Our first movie was a good one, an old favorite of mine (and of many of my friends as well): John Sayles’ 1994 The Secret of Roan Inish.

Folklore emerges quite directly in this film, as it constitutes the heart and identity of the protagonists. Roan Inish adapts the legend of the selkie, a not infrequent character of Celtic and northwest Teutonic folklore. These creatures swim as seals in the sea, but on land can take human form. Selkie stories are almost always love stories, and more often than not, they end in loss. Take, for instance, the Highland tale of Loch Duich:

Three brothers went fishing in Loch Duich one night, and came upon a fantastic sight. A group of seals came ashore, slid out of their seal skins, and began dancing on the silvery sands. The three brothers could see their human forms and human skin glinting in the moonlight. Falling in love, the three brothers stole the seal skins of three dancing girls, who were unable to slip back into the sea as seals. Seeing his chosen partner begin to weep, the youngest brother took pity and returned her seal skin, allowing her to swim home. But the two older brothers took the seal-maidens as wives.

Nine days later, the party of seals appeared. The elder brothers feared to lose their wives, and shut them away. But the youngest brother only gazed with love at the seal-maiden he had set free. Then her father appeared. He said that his daughter was equally in love, and as a reward for his kindness, he would allow his daughter to return to him every ninth night. The youngest brother and his seal-maiden were overjoyed.

But the two elder brothers did not enjoy such a happy ending. One seal-wife found her skin again and left her husband and children forever. The other brother, thinking his own wife would do the same, burned her seal skin. The moment flames touched the skin, the seal-wife also burst into flames and perished.

Tales like this share three elements: entrapment (via theft of the skin), abduction, and escape. Such a cycle calls to mind not only the relentless rise and fall of the sea in which selkies swim, but also the rise and fall of generations of families who tell and retell this legend as part of their unique history. (This actually happens, by the way; in 1895 the Shetland woman Baubi Urquhart claimed to be a descendant of a seal.) In contrast to the harshness of the tale of Loch Duich, The Secret of Roan Inish does take certain pains to illustrate the mutual interest of seal-maiden and youth (given the names Nuala and Liam). Nevertheless, the film portrays the three elements of entrapment, abduction, and escape: once Nuala learns where Liam had been hiding her seal skin, “neither chains of steel nor chains of love” would hold her.

There is an interesting parallel in another family story recounted in the film. Fiona Coneelly’s grandfather’s great grandfather Sean Michael left his home to attend school. As Fiona’s grandfather narrates, the “English were still a force in the country then…it was their language and their ways that you had to learn there.” Caught speaking Irish, Sean Michael is chastised by the schoolmaster and forced to wear a cingulum like a yoke about his neck, a captive of this strange English schoolmaster and his strange English ways.

Unable to bear this cruelty and the taunts of his schoolmates, Sean Michael refuses to continue and escapes back to his family and home. In much the same way, the selkie Nuala is forced to live among a strange people. Indeed, the film emphasizes how strange the islanders found her in turn, speaking Irish that was “queer-sounding, more ancient than their grandfather’s grandfather’s.”

Nuala’s tremendous joy at returning home as a seal is echoed in Sean Michael’s determination to return to the “black rocks and the wild waves and the hard sky above.”

Soon after Sean Michael’s escape, he is caught in a great storm and shipwrecked. We discover that he is borne to shore by a seal. Seals are common in folklore and myth; seal-riding, on the other hand (or flipper, as the case may be), is not. This scene reminded me of an Icelandic folktale in which a human is carried by a seal-that-is-not-a-seal to shore. This was first collected by Jón Árnason (Icelandic librarian, museum director, and author) in his 19th c. compilation of Icelandic folktales*.

As the story goes, the priest Sæmund the learned enters into a deal with Kolski (The dark one, the devil). If Kolski can transport Sæmund across the sea to Iceland without getting any of Sæmund’s garments wet, then he can have Sæmund’s soul. Kolski takes the shape of a seal, and the two are off. The seal swims along so smoothly that not a drop of water touches Sæmund’s robe. Sæmund, however, is so absorbed in reading his Psalter that he scarcely notices. Then, just as they are about to reach the shore, Sæmund suddenly lunges out and bops the seal on his head with his Psalter. The seal goes under, Sæmund is drenched with seawater, and the story ends with the priest once more evading the devil.

Here’s a statue at the University of Iceland depicting the bopping. As you can see, none of Sæmund’s garments could possibly get wet, since he isn’t wearing any! In some versions, Kolski can’t let a drop of water touch Sæmund’s foot instead.

Sæmund stories tend to feature him outwitting Kolski in this way. These are tales of magic (galdrasogur), trickster tales, entirely different in type and register from the scene in Roan Inish. One seal seeks to save some poor soul, and the other would steal someone’s poor soul. Yet it’s not an insignificant detail that in both instances it is a creature merely in seal form that bears the rider, not a true seal. We see people riding dolphins in Greek myths, whale-riding in Maori folklore. Why is seal-riding so uncommon?

I’d like to draw attention to one more matter. When the selkie in Roan Inish transports the Sean Michael from sea to land, world to world, she also transports him—and us—to a different reality in which the impossible becomes plausible. The supernatural is natural, and the laws of order are turned upside-down. We suddenly understand the dynamic of the film in another light. In terms of theoretical physics and parallel universes, we might call these wormholes. Rabbit holes, wardrobes in spare rooms, peaches, fairy dust, swinging ropes. All devices that inform the audience of a change in reality and expectation. Jamie’s cradle-boat (featured below) in the film functions in a similar way, for having been imbued by the seal-woman’s awareness and magic, it conveys little Jamie back and forth between the world of humans and selkies. It also has a temporal dimension, conveying generations of Coneelly children across decades, from the time of the original seal-mother to each subsequent encounter of the children with the seals and selkies. I’d like for this blog to operate in a similar way, as a guide and reminder of this shift as we explore many different parallel universes in literature and film.

(*) The Icelandic text can be found here on page 494 and in English here