March 8: It is International Women’s Day; what better occasion to celebrate with a recent book by a woman about a woman?

March 8: It is International Women’s Day; what better occasion to celebrate with a recent book by a woman about a woman?

It is a long time since I read a biography of a photographer that is as compelling, and as touching, as Helen Ennis’s 2019 Olive Cotton: a life in photography. In the interest of objectivity, I’ve avoided others’ reviews, though it is impossible to close one’s eyes to the awards that the book has already garnered.

Olive Cotton (2011–2003) achieved notability twice in her lifetime, and twice was in charge of her own studio business. What is most poignant about her story, and what is the main substance of this book, is what came between, and after. Her first brush with fame came in 1938, at age 27, which was;

… an auspicious year, in which she outstripped the achievements of many of her fellow exhibitors. No other woman photographer was represented in the two most talked about exhibitions in the country, the Australian Commemorative Salon and the Contemporary Camera Groupe’s show. Furthermore, she received substantial international endorsement with her second showing at the London Salon of Photography, which hung both Shasta daisies and Winter willows. Even more significantly, Winter willows was published in The Penrose Annual: Review of the graphic arts, where it was discussed [in an article “Art in Photography”] by Jan Gordon, art critic for the English newspaper The Observer and occasional reviewer for the annual. [an edition notable for its text, jacket and binding by legendary Modernist designer Jan Tschichold].

Ennis’s chapter ‘Great Possibilities’ tracks Cotton’s trajectory from her ‘first public debut as a photographer’ in 1932 at age 21 when her Dusk was displayed in the Interstate Exhibition of Pictorial Photography by the Photographic Society of New South Wales of which she had become a member. The title of the exhibition is apposite; the execution of Dusk adheres to the tradition of Pictorialism which promoted an imitation by photography of traditional painting and printmaking. It was a style that even then was being rejected as anti-photographic by those with modernist ambitions, but Ennis identifies in this “competent, pretty and modest work” Cotton’s attachment to the ‘key tenets’ of Pictorialism in “her entire output…the evocation of beauty, stimulation of the senses and emphasis of the effects of light.”

Cotton’s rediscovery came not until…

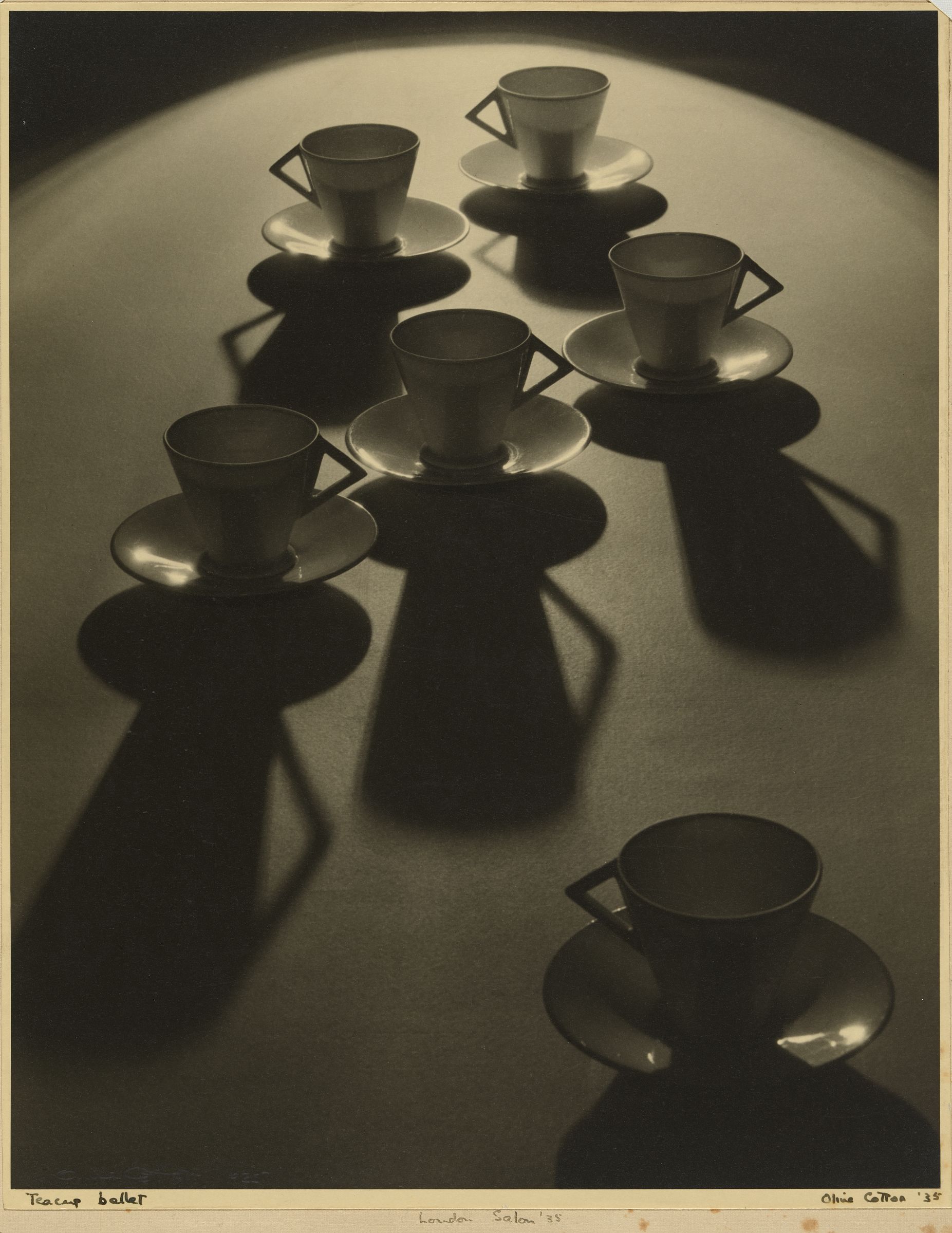

In 1980, Gael Newton, inaugural photography curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, selected Teacup ballet and Glasses for her book Silver and Grey: Fifty Years of Australian Photography 1900–1950. The book was the first to place Olive’s work in the historical context of Australian fine art photography, as historians and curators of photography began constructing a lineage of modern photography. She was in prestigious, better-known male company – Cecil Bostock, Harold Cazneaux, Max Dupain, David Moore and Wolfgang Sievers were some of the inclusions.

Barbara Hall and Jenni Mather, pioneering feminist historians of Australian women’s photography, staged Australian Women Photographers 1890–1950 at the George Paton Gallery in 1981 with support from its interim director Judy Annear (later senior curator photographs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales), and published a book of that title in 1986, that included a biography of Cotton and again Teacup Ballet, with her Design for a Mural (1942) and Girl with Mirror (1938).

Olive Cotton: a life in photography more than satisfies prevailing curiosity about Cotton’s romantic and professional association with the once better known Max Dupain — they were teenage sweethearts who met through their families, hers being the better-heeled, on holidays on the NSW coast where they shared a devotion to photography (increasingly competitive, though sportingly and in mutual admiration, as Ennis reveals). Thus is established a complex relationship between them. After studying at university and rather than going into teaching like her aunts, Cotton “made the first of her overtly adventurous and independent decisions” and in 1933, against her father’s wishes, joined Dupain in his ‘Bond Street operation’; the studio he had set up with parental support, in Sydney after apprenticeship with Cecil Bostock, detailed in a separate chapter, had run its course.

By then they were not only partners, but lovers. However Ennis points out that Olive did not “enter into it on an equal footing” and “did not take photographs in any professional capacity and instead oversaw the administrative side of things” and eventually some darkroom printing, she notes their “use of the collective pronoun ‘we'” in Cotton’s later published comments about the business. What drove the ‘operation’ was Dupain’s ambitious modernism, the spirit of which arrives belatedly in Australia through channels like the visits of the Ballet Russes and the Budapest String Quartet (whom Cotton photographed) and that Ennis elucidates in ‘Being modern’.

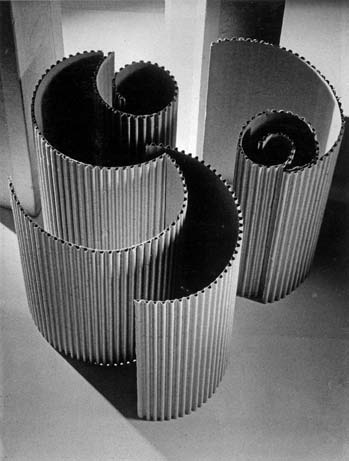

Though emphasising throughout that Cotton rarely gave voice to her aesthetics and opinions on other practitioners, Ennis discovers in unpublished notes, her admiration, actively shared with Dupain, for Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy, Edward Steichen, Margaret Bourke-White and Bill Brandt which she encountered in imported publications (though Dupain’s favourites were the more commercial successes). It is this zeitgeist that inspired Cotton’s still life imagery, starting in 1934 with Cardboard design which joined three others in one edition of the handsome Bank Notes staff magazine of the Commonwealth Bank in which Teacup ballet was to appear in 1937.

The title Cardboard design makes it clear that it is an essay in pure, non-applied design, the wellspring of which was the Bauhaus, just then being threatened in Germany with the rise of the National Socialists.

While Ennis pays close attention to the composition and lighting of these photographs, they, and Glasses (above) are non-commercial impromptu technical exercises carried out in her own time and through which Cotton learned more sophisticated skills in the use of Max’s Thornton Pickard half-plate studio camera, such as the tilting of its lens board and film holder to achieve deep focus.

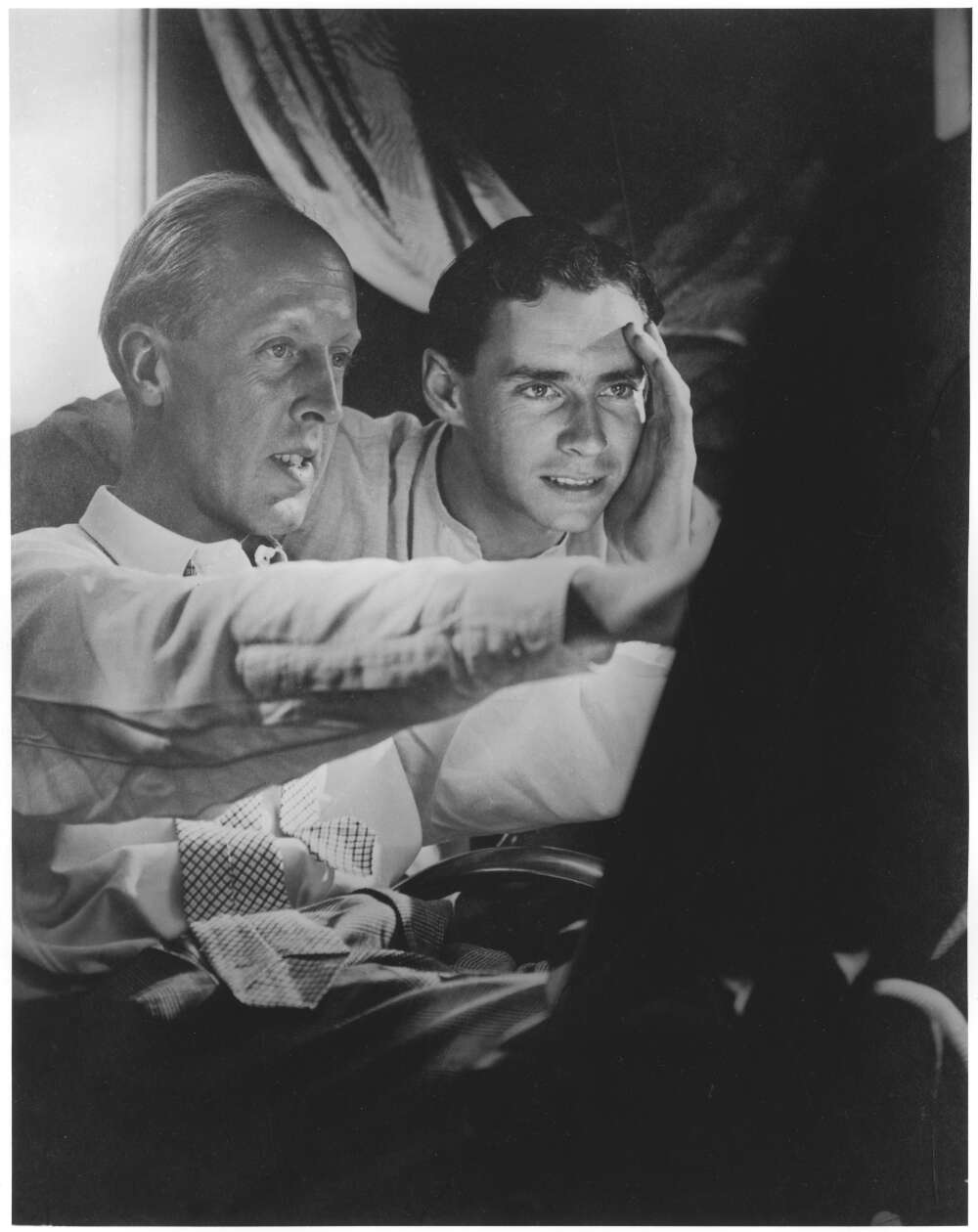

One episode that conveys Dupain’s youthful, even boyish, delight in his fast-advancing ambitions is the arrival of the eminent Russian-born fashion photographer George Hoyingen-Heune, then working for Conde-Nast in New York, who for five days visited Sydney on an Asian cruise in December 1937. He was pictured by Dupain’s assistant-cum-junior partner that the business could now afford, Geoffrey Powell. He captures Dupain’s rapt attention to the sophisticate master who, resplendent in his deliberately negligee luxurious silk tie, makes a point about lighting in the mounted print they discuss.

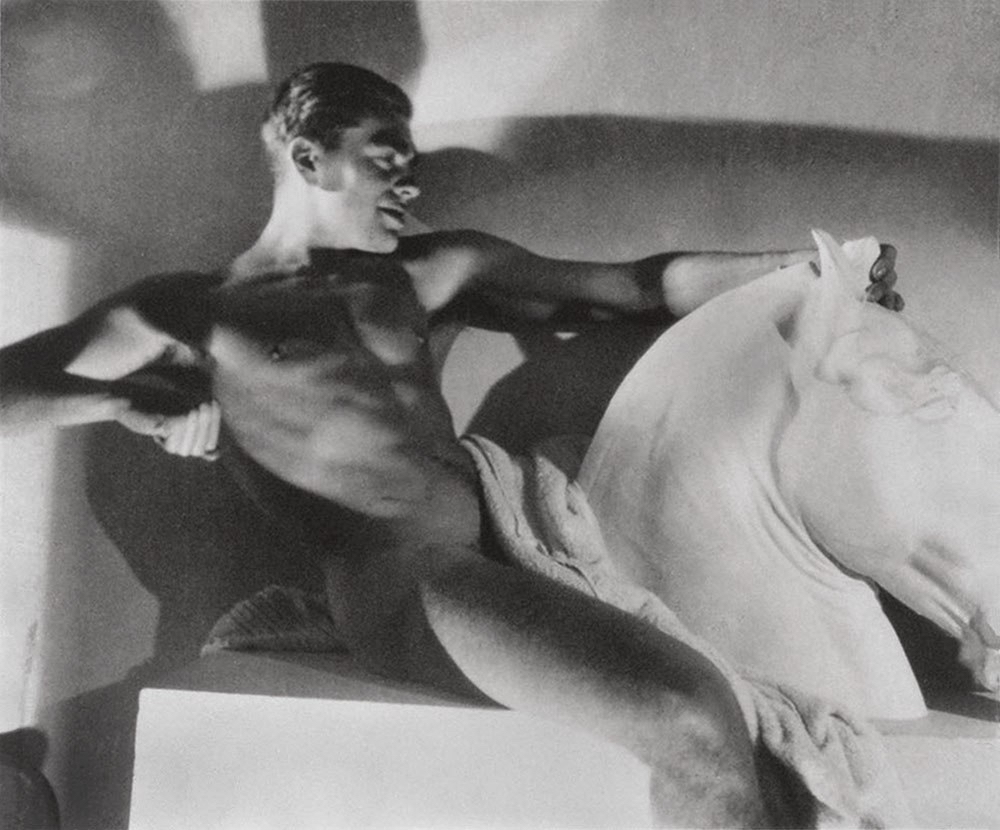

A frequent visitor to the studio to fulfil commissions as his services were eagerly sought by the David Jones fashion house, there is intrigue around an exhibition print owned by Max of Olive’s Max after surfing that is signed by Hoyingen-Heune “To Max with friendship from George” on the border.

A smaller unsigned print, much darker in the shadows, was printed by Cotton (the later print above duplicates her version) while the negative was retained by Dupain and returned to her by his darkroom assistant only in 1992.

Why the former version is signed for Dupain without reference to Olive and whether the Baron had supervised the printing is not explained by Ennis more fully than did Gael Newton in her 2007 essay published in Antiques & Art. The truth is unavailable. Above all the existence of the signed print confirms Cotton’s low status in the studio.

Though further facts have not been uncovered, Ennis does throw some further light on this mystery from her interviews with Sally and Ross, Olive’s daughter and second husband, hinting that perhaps the photograph was set up by Max, though one would think its art direction might be Hoyningen-Huene’s, especially given his homoerotic male nudes represented as classical, bas-reliefs. The shallow depth of the image is unalike the open spatiality of Cotton’s studio work and depictions of figures in the landscape.

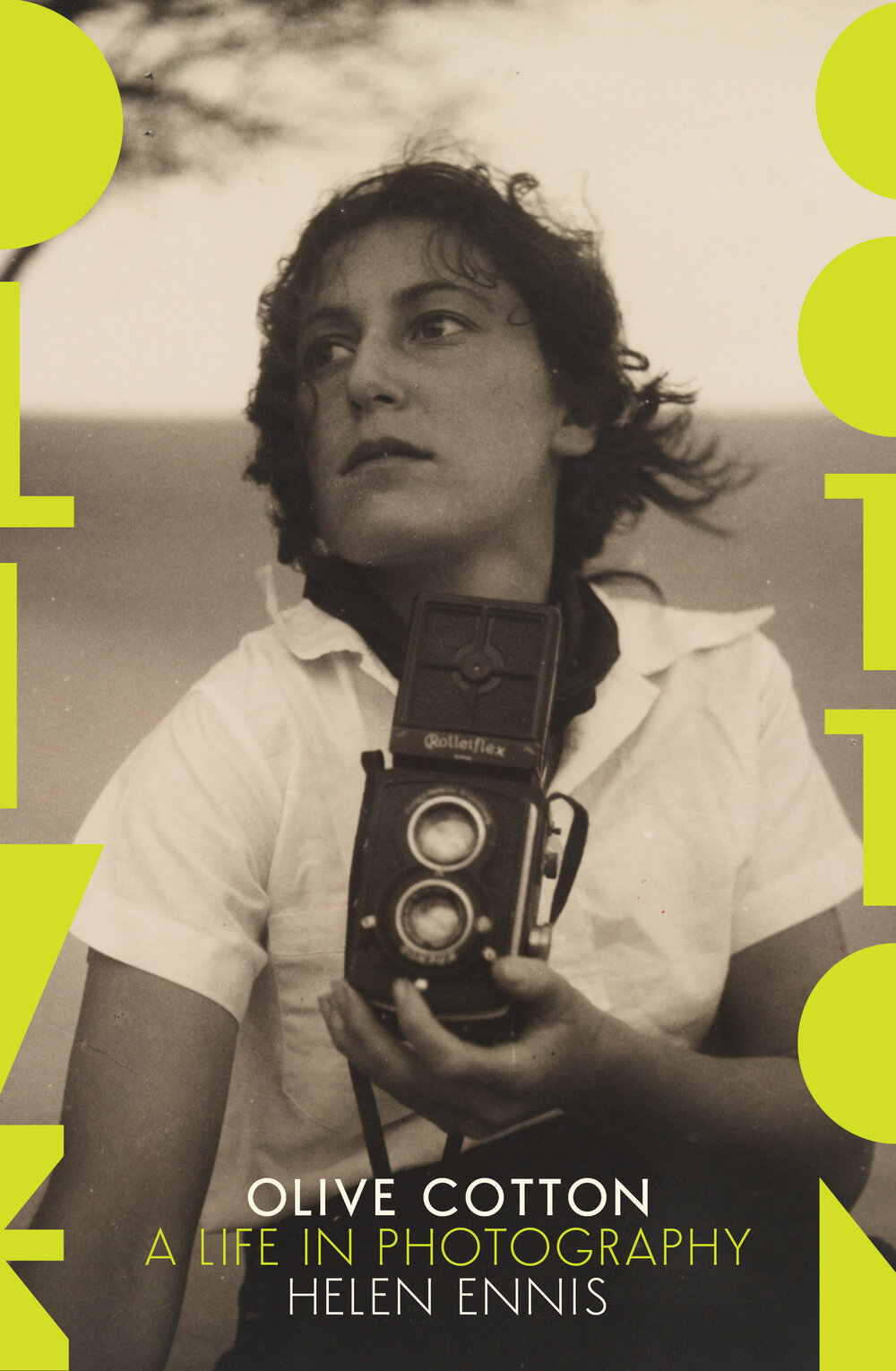

Cotton only came to own a professional camera, the Rolleiflex that appears in her hand on the cover of the book, in 1937. Max, in a portrait that is clearly adoring, two years before their marriage, shows her cupping it tenderly in one hand. Apparently unaware of being observed, her dark eyes, haloed by wild, wind-blown hair, search out a subject. They are echoed in the twin lenses of the camera; reflecting skylight their light tone might be read as the white of her shirt, so make the camera appear empty, a receptacle waiting to be filled.

Cotton only came to own a professional camera, the Rolleiflex that appears in her hand on the cover of the book, in 1937. Max, in a portrait that is clearly adoring, two years before their marriage, shows her cupping it tenderly in one hand. Apparently unaware of being observed, her dark eyes, haloed by wild, wind-blown hair, search out a subject. They are echoed in the twin lenses of the camera; reflecting skylight their light tone might be read as the white of her shirt, so make the camera appear empty, a receptacle waiting to be filled.

Sandy Cull designs the dust-jacket so that this striking portrait of the book’s subject at the apogee of her early career is displayed between truncated letters that would spell her name, but become voguish Deco ornaments in the smoky and neon tones of a cinema foyer of that era. The picture might have been made at the same time that Olive was making pictures of Max photographing fashion models on the sandhills at Cronulla (above). They contain a hint of her fears that his attention was wandering from her to his models, a tendency culminating in his attraction in 1941 to an eighteen-year-old National Art School student Diana Illingworth. He married her in 1944 after his separation from Cotton and a divorce protracted by the requirement of establishing onus of fault, which they agreed would be borne by Olive on the grounds of desertion (she had left in June 1941 to teach at Frensham school 120 km from Sydney). In concluding her chapter ‘The bust-up” Ennis quotes long-time friend of the couple Ernest Hyde; “Max was a very demanding person and Olive was a very giving person.”

Her watchful eyes of the cover photograph are also indicative of her new concentration in the late 1930s on flower studies and landscapes, and ‘Figures in the landscape’, the title of a chapter that plays Dupain’s famous masculine Sunbaker of about 1938, which in an interview with Ennis he named “an icon of the Australian way of life”, against Cotton’s Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind and The sleeper, both of female friends, model Jenny Brereton and photographer Olga Sharp, in 1939, the year of their ill-fated wartime marriage.

These are not portraits, as Ennis emphasises, but the imaging of a sensuous empathy for a state of human immersion in the landscape, and while Sunbaker generates such a sensation, she points to its modernist geometry as a point of difference from Olive’s softer, psychologically and physically close proximity with her subjects.

In ‘The company of women’ the reader is given further evidence of this sensitivity in nude photography on the beach commissioned by Joan Baines who contacted her to make pictures she could send to her husband in the AIF in Palestine.

Held by the Art Gallery of New South Wales and rarely seen, these are profoundly moving, frank expressions of passion fervently transmitted through Olive’s compassionate, complaisant lens.

Four ‘Really great years’ came for Olive during the war when publisher Ure Smith, a client of the studio, asked her to take it over to produce work for him on a salary and part of profits. The war put an end in 1942 to his publications The Home and Art in Australia that had provided so much income and exposure for Dupain, sufficient to support one other photographer (Damian Parer or Powell) and Olive as assistant. He started another, Australia National Journal and though work was so scarce that Cotton could turn down none, she came into her own, producing some of her best work during this short period 1942 till late 1945 when Max returned from his war service in the camouflage corps.

Ennis provides an example in a complex montage design for a six-foot mural for architect Samuel Lipton, but denies other photo historians’ claims that it is a Surrealist work. She does not go so far as to say it shares much with the genre of the ‘table-top’ that disgraces so many British Journal of Photography annuals of the period. What makes Cotton’s a superior example is the fact that the ballet dancers are not china ballerina figurines but skilful, consistently-lit montaged multiple poses of a real model, the photographer’s fastidious finesse creating a believable stage-set for fantasy.

This image appears on a page almost exactly half-way through Olive Cotton: a life in photography, and it marks the end of the story most of us may know about its subject from the 1995 Olive Cotton, photographer (photographs and captions by Olive Cotton ; with an introduction by Helen Ennis ; and personal memoir by Sally McInerney).

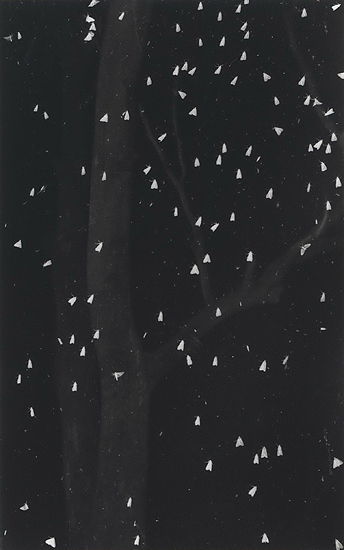

Details from ‘The Dupain diary’ and of the ‘Divorce’ come in the following chapters which unlike most previous, have no accompanying illustration. Ennis keeps each episode to its own short, polished chapter, though (as I am reflecting in this review) not in strict chronological order. Each is given a short, pithy title such as one might give a photograph, and in keeping with that, the picture they include (almost all by Cotton) provides a point of contemplation. Documentary and family photographs are given a quire of glossy pages, while the images in the chapters come to us on the same off-white fibrous paper as the text. Though it may be intended to imitate the photographic papers of the era, and though I am sure McPhersons printers took every care, it sucks the life out of the blacks, making important detail in the less familiar but pivotal images Moths on the windowpane and Light and shade unreadable. You may find yourself, like I did, using phone or tablet while you read, to look up decent online renditions of these great pictures where they are provided by institutional collections, the NLA, NGA, AGNSW, NGV and on the dealer Josef Lebovic’s site.

Part Four (there are 6 parts, each with about 12 chapters) starts its first chapter ‘Meeting Ross’ with a photographic introduction to him on the facing page which brings visceral understanding of his attractiveness to Olive. Where some commentators find the semi-nude Max after surfing an ‘erotic’, ‘swoon-inducing’, ‘sexually-charged’ ‘Adonis’, this picture, made during the escalating war while Cotton was in the midst of running the Dupain studio is the portrait of…

…”a relaxed, fit young man dressed in army uniform…half-smiling…slightly self-conscious but intimate nonetheless” … “the man who would become her second husband invite[s] comparison with Max after surfing, because of [the portrait’s] erotic power. The differences are telling. Olive photographed Ross with no coyness or obfuscation and his eye contact introduces a directness that is absent from the elaborate set-up with Max.”

He was the brother of John who married Jean Lorraine — seen above in Cotton’s experimental candlelit portrait — who was originally a Dupain model but soon a lifelong intimate of Olive, a blithe and liberated foil to her conservative nature, whose letters and interviews provide much of the information for this second period in Cotton’s life when she ‘went bush’, and when for Ennis “her biographical shape becomes curiously insubstantial, shadowy at best.” She seemed to many to have vanished from the photography scene, after her marriage took her first to live in a tent on McInerny’s father’s property in the Ilunie Range, forty-five kilometres south of Cowra, in April 1946 where she was pregnant with her first child Sally, then after the birth of her son Peter, to nearby Spring Forest several miles from tiny Koorawatha and 300km over the Blue Mountains from Newport, a distance she frequently traveled to stay with her parents there as some relief from a rough rural existence.

The marriage was, as his son-in-law wrote, an ‘Invitation to Poverty’; Ross never made good on grand ambitions to become ‘a grazier’ as he described himself on their wedding certificate, leaving their 500 acres largely uncultivated, and he harboured a resentment borne of his conviction for Absence Without Leave when he absconded to assist on his father’s property during the drought that exacerbated wartime privations and financial misfortune that preceded it. It is clear that he survived a sense of failure on Olive’s constancy, and constant reassurances. A brilliant raconteur, he is often portrayed here, heroised even, by Geoffrey Lehmann, daughter Sally’s husband, in excerpts from his book of poems, Spring Forest (1978), which the poet explains ‘is spoken through the voice of a living person, Ross McInerney of Spring Forest, Koorawatha, and much of it is based around his life and stories’.

Olive Cotton: a life in photography begins with Ennis’s opening of “The trunk” found amongst other abandoned items on the dilapidated enclosed back verandah — Ross’s bedroom — of the ‘old house’, their first home on their property Spring Forest after August 1949. The business, personal and love letters (though Cotton destroyed those she wrote), documents and photos contained in it are primary sources for Ennis’s long-term research, that and Spring Forest itself, as she explains in the Australian Book Review July-August 2013 in relation to its ABR George Hicks Foundation Fellowship which bought her time to devote to this book;

“Visiting the home or homes of your biographical subject is a standard ploy, part of the biographer’s immersion into all possible aspects of their subject’s life. I see it as being intrinsically linked to the physical journeying – the ‘footstepping’ – that English biographer Richard Holmes writes about so well. The assumption is that the retracing and immersive processes, coupled with the scrutiny of personal papers and public works, will provide a means of accessing and understanding the subject’s interior life; a way of forging an empathic connection with their thoughts, feelings, states of mind. By any measure, Spring Forest should be a boon…” [which] “I have been visiting…for twenty-eight years, first as a curator of photography, then as a family friend, and now as Olive’s biographer. In my new guise, Spring Forest has been transformed from a lived-in environment to something akin to an archaeological site. In its latest incarnation, it has one overwhelming characteristic – excess. It is quite literally laden with artefacts. If all the things cramming the house and yard were sounds, the noise would be deafening. “is has a curious and paradoxical effect. I find myself struggling with apparently contradictory states, with both an excess and a lack. In this surfeit of stuff, I am not sure where to find Olive Cotton.”

Olive’s daughter Sally Lehmann contributed her essay ‘Life in the Country’ to the earlier Olive Cotton, photographer. Cotton also speaks in the documentary film entitled Light Years, by Kathryn Millard (1991). Other primary documentation is in the form of the records of interviews Cotton gave journalists, curators, and photography historians when in the 1980s she reappeared in the world of photography.

Even though Cotton “kept taking photographs with my old Rolleiflex camera and had the negatives developed at the town chemist, always with the thought that one day I might get a darkroom of my own and be able to print my negatives” and though after her children had left home, she started a new wedding and portrait studio in Cowra, her isolation and sometimes, one might suspect, a psychologically difficult —sometimes abusive? — marriage to a reclusive, damaged man, represents a dire experiment in cultural confinement, away from the rapidly evolving developments in photography over the second part of the century. That is evident in the pictorialist sentimentality of her 1953 photograph Children’s garden in its careful framing and symbolism of youth against a background of blossom trees and grazing lamb, though she had hopes the picture might join others in a book on country childhood with words by her friend Jean Lorraine, then living far away in America but still corresponding with her.

In an earlier, 2012 discussion on the process of writing this book (the gestation of which was unsurprisingly protracted; it is Ennis’s tour de force), in The Space of Biography: Writing on Olive Cotton (Meanjin, Volume 71, Number 3, 2012) she admits she did not feel she could begin to write until after the death of Ross McInerney in 2010. In the essay, Ennis describes her ambitions for the biography;

“I want my writing to synchronise with the pace of Olive’s life and the qualities of her photography. From my experience of Olive, whom I met in 1984, she never rushed to speak, never rushed to fill in silence with a rude shock of words. Always she left a space around her. As for the tenor of her photography, her first husband, fellow photographer Max Dupain, summed it up in an eloquent review of her exhibition in 1985 that was published in the Sydney Morning Herald. He wrote: ‘The therapeutic calm of this exhibition is its major attraction. It’s like walking through the bush early in the morning and suddenly being surprised by a tranquil lake.”

Imagining the book she has not yet written Ennis boldly foresees…

“…how the words appear on the papery pages, open with space around them. The font is classic, Bodoni perhaps, or Garamond. Reproductions of Olive’s photographs are full page and commanding. The book itself is a beautiful object, its weight just right for hands to hold on the couch or in bed. A book for pleasure, not for duty.

My quibble about the way the paper saps the printing of the images aside, and it is an illustrated book, not a ‘photobook’, but is is a book worth having, not least because of the input of collaborators, for its design — the typeface is in fact Bembo, still a Renaissance classic — set by Australian firm Kirby Jones and for a fabulous index by Kerryn Burgess, invaluable in its rare thoroughness as an aid to those who would read this ‘for duty’ and who will appreciate the extensive endnotes.

Hidden behind the dust jacket, slightly cropped top and bottom to wrap entirely around the hardback cover is what Ennis considers Cotton’s earliest successful photograph, an essay in light and shadow made at age 22 in the bedroom she shared with her sister. It is an image with corresponding lateral centres of interest that copes with such a presentation to become in effect two pictures on the front and back covers, while the thick spine catches in a perpendicular the Japanese print on the wall and the plum blossom that sits like a Japanese printmaker’s chop at the base.

The book prompts a new appreciation for Cotton’s later work of the 1990s. Though they still retain an anachronistic pictorialism in both arrangement and printing — from 1980 Cotton used her commercial studio in Cowra to print for her dealer Josef Lebovic, staying overnight so that she could concentrate — they are rewarding and profound in their meditative affect, the work of a mature artist who has lived life adventurously.

Where Interior draws our attention to an Art Nouveau form that manifests in the shadow on the wall and seems to rise from the vase of bursting blossom, in Vapour trail of 1991, made when she was 80, the source of a more energetic plume in a vast sky, the tonal negative of Interior’s shadowy abstraction, seems to emanate from broken, dead limbs of a tree at the extreme corner of the print. For Ennis, referring to Edward Said’s prospect of death, “Olive’s late works…leave an overwhelming impression of ‘harmony and resolution’, rather than the discordance Said wrote about so forcefully.”

None express this more forcefully than Moths on the windowpane, photographed from inside their newer house (a relocated demountable) at Spring Forest against the trunk of a tree seen dimly outside. Ennis again invokes Said:

“Lateness is being at the end, fully conscious, full of memory, and also very…aware of the present.”

For further insights into this extraordinary story, you can listen to Helen Ennis in interview at the launch of Olive Cotton: a life in photography on 28 November 2019

Olive Cotton features in Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now until 4 July 2021 at the National Gallery of Australia, an initiative which “aims to increase the representation and understanding of artists who identify as women through a series of events, commissions, creative collaborations, publications, partnerships and exhibitions.”

Another great piece James…thank you, I really enjoyed that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank Brian…I enjoyed Ennis’s book!

LikeLike

Always important to recognise the work of great photographers who happen to be women – thank you for introducing her to me.

LikeLike

Glad you read it…Cotton was very nearly a forgotten talent, only rescued by the attention of other women, and now almost every Australian would recognise her ‘Teacup ballet’ as easily as they would Dupain’s ‘Sunbaker’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s certainly true that after the 1940s she was almost unknown among city people, but from the early 1960s onwards, she became well known in the Cowra community as a photographer and friend, and many people in that community still have her photographs in their houses.

LikeLike