Visual disturbances, transient or continuous, are associated with a variety of headache disorders, including migraine with visual aura, retinal migraine, visual snow syndrome (VSS), and Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AWS). The prevalence of aura is estimated to be up to 33% in people with migraine.2 Visual auras are most common, occurring in approximately 98% of persons with a diagnosis of migraine with aura.3 Considering this high prevalence of visual aura and growing recognition of other visual syndromes associated with migraine, it is prudent for practicing neurologists to recognize the intricate relationship between vision and migraine.

Visual Auras

Visual auras are complex, focal, transient neurologic events involving visual impairments that occur most often before or during the headache phase of a migraine attack and are attributed to a mechanism known as cortical spreading depression (CSD) (see Migraine With Nonvisual Aura in this issue). Migraine with aura is formally defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) as recurrent attacks of gradual symptoms of reversible visual, sensory, or central nervous system symptoms lasting minutes and followed by headache and migraine symptoms.4 The diagnostic criteria require at least 2 attacks with 1 or more fully reversible aura symptoms, and at least 3 of the following features: 1) aura spreading gradually over 5 minutes; 2) 2 or more auras occurring in succession; 3) aura symptoms lasting 5 to 60 minutes; 4) unilateral aura; 5) positive aura; or 6) aura accompanied or followed by a headache within 60 minutes.4

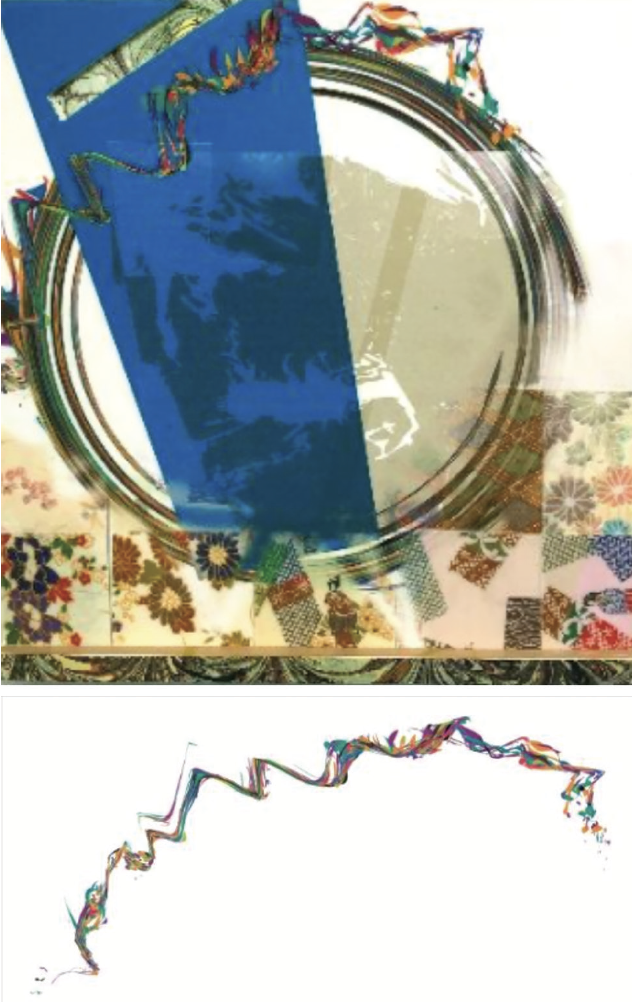

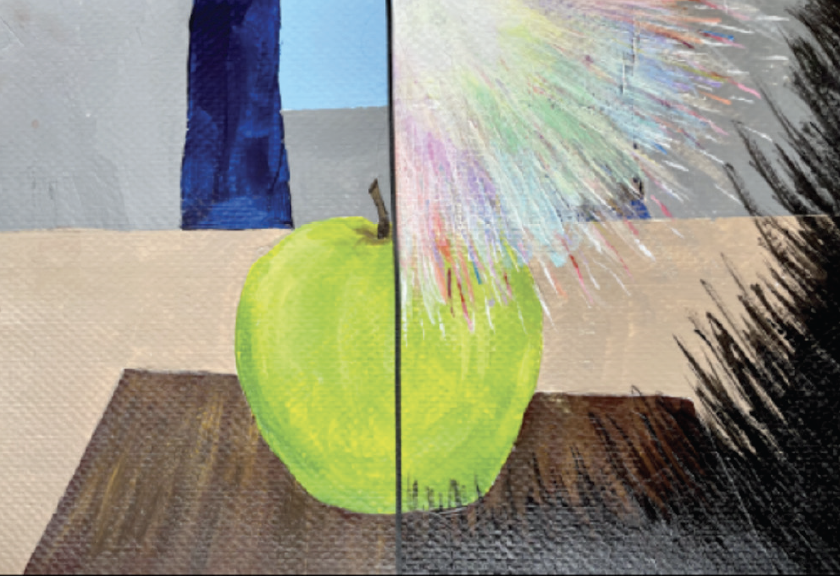

Visual auras are subjective and uniquely evolving events; thus, their descriptions are variable, with some commonalities across individuals. Visual auras can be categorized as positive or negative. Positive symptoms typically occur first and are more common. Some examples of positive symptoms include bright flashing lights, zig-zag lines, colored spots, blurred vision, and scintillations.5 Rarer positive symptoms that have been described include geometric hallucinations, metamorphopsia, micropsia, macropsia, teleopsia mosaic vision, and palinopsia, (Table 1).6 In contrast, a visual field deficit is the most common negative visual aura described.5

The prototypical scintillating scotoma is a spreading blind spot with brightly colored flickering of a jagged crescent shape of light.7,8 Examples of scintillations with or without scotoma are portrayed by artists who experience them in Figures 1 and 2 and on this month’s cover. Scintillations are poetically described by Chuck McCoy, as a subtle river of distortion around the eyes illustrated as a migraine river that can progress into closing-up of sight (see About the Cover Artist in this issue).

Classifying visual auras into positive or negative symptoms can help distinguish migraine physiology from other neurologic conditions, notably transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and seizures. A gradual-onset disturbance with progression across the visual field, evolution of symptoms from positive to negative, and binocular involvement is more compatible with migraine pathology. By comparison, a monocular visual field deficit, such as a blind spot that is often described as a descending curtain, is a negative symptom that would be more compatible with amaurosis fugax, whereas a sudden onset binocular visual field cut, often with other neurologic deficits, is concerning for cerebral ischemia (Table 2). Visual aura lasts 5 to 60 minutes. In contrast, occipital lobe seizures are brief and typically present with positive visual phenomena (eg, elemental shapes or well-formed hallucinations), lasting approximately 3 to 5 minutes.6 With such a heterogeneity of described visual symptoms, various tools have been created (eg, the visual aura rating scale [VARS]), in attempt to establish a formulary objective approach for guiding a diagnosis.3

Retinal Migraine

The presentation of monocular scotoma, transient monocular total vision loss, or field defects followed by a migraine headache, describes a very rare reversible visual phenomena known as retinal migraine. To meet diagnostic guidelines, attacks must fulfill criteria for migraine with aura and the visual symptoms should be gradual, last 60 minutes or less, and be associated with headache at onset or within 1 hour. Patients can easily mistake visual field defects as monocular symptoms, however, and the monocular aura thus needs to be confirmed by having patients draw each monocular visual field or be examined during an attack. An aura diary to document frequency, duration, and characteristics can also help clarify visual symptoms. Importantly, there is clinical overlap of the presenting symptoms of retinal migraine and amaurosis fugax, which is a broad term describing vascular causes of transient monocular vision loss (eg, giant cell arteritis, retinal vasospasm, or retinal embolism).9 Because retinal migraine is a very rare cause of transient monocular visual impairment, further investigation and examination should be conducted, in patients without prior history of the condition, to rule out alternative causes, such as amaurosis fugax.

Aura Status and Persistent Aura Without Infarction

Persistent migraine aura without infarction (PMA) is defined under complications of migraine in the ICHD-3, whereas migraine aura status is an appendix diagnosis.10,11 The criteria for migraine aura status requires at least 3 auras over 3 days vs at least 1 week for a diagnosis of PMA. Both these diagnoses should only be considered after vascular symptomatic aura etiologies (eg, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome [PRES], vascular dissections, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome [RCVS], and cerebral ischemia) have been excluded by MRI including vascular imaging.10,11 If symptoms of an aura linger in between the timelines of these 2 diagnoses, lasting more than 1 hour but less than 1 week, there is no specific aura category defined, and the broader diagnosis of “probable migraine with aura” is the most current categorization. Analysis suggests, however, that at least 11% and possibly up to 30% of persons with migraine with aura have an aura lasting more than 1 hour, leading clinicians to suggest improved diagnostic clarity is needed to address this prolonged aura.6,12,13

Migraine With Aura and Vascular Risks

Migraine with visual aura is associated with cardiovascular disorders, including increased risk of atrial fibrillation, patent foramen ovale (PFO), and ischemic stroke.5,14,15 Growing evidence indicates people with migraine have a twofold increased risk of ischemic stroke, and there is an increased risk of cardioembolic stroke in persons with migraine with visual aura compared with those without aura.16 The absolute risk of stroke associated with migraine is low (4 additional ischemic strokes per 10,000 women/year when migraine is the assumed cause of stroke according the American Stroke Association Guidelines17), but these cardiovascular risks are higher among women who have migraine with aura, especially those who use estrogen products, are under age 45, use tobacco, and have higher frequency of migraine attacks.18,19

The use of hormonal contraception in people with migraine of childbearing potential remains a controversial topic as it relates to stroke risks. A case-control study assessed stroke risk in persons with migraine who used combined hormonal contraceptives over a 6-year period; the calculated relative risk score was 8.72, a sixfold increased risk of ischemic stroke, with use of combined hormonal contraceptives in persons with migraine with aura, compared with people with neither risk factor.20 The 2017 consensus statement review from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC) stated that products with greater than 35 mcg of estrogen are considered high risk, combined contraceptives with less than 35 mcg of ethinylestradiol are considered medium risk, and progestin-only products have no additional risks in those who have migraine with aura.21 In conclusion, the consensus review strongly suggested nonhormonal contraception or progestin-only options for people with migraine with aura. Despite the poor evidence for the risk of ischemic stroke associated with hormonal contraception in people with migraine, there are no clear data to support the safety of combined hormonal contraceptives in women with migraine in regard to ischemic risk. Thus, the current recommendations remain more restrictive at the prioritization of patient safety considering the potential for devastating, life-long deficits from an ischemic stroke and because there are effective, safer alternatives.21

Migraine With Aura Diagnostic Investigation

The workup for people presenting with migraine with aura, a clinical diagnosis, starts with a thorough history, followed by a comprehensive neurologic and ophthalmic evaluation. Additional evaluation is not indicated for those presenting with symptoms meeting criteria for migraine with aura who have no findings on neurologic examination. If visual symptoms raise concern for a vascular etiology, then the patient should be evaluated with head imaging (either a CT with and without contrast or MRI). MR angiography and venography should be added based on the suspected differential. Very rarely, if there is difficulty discerning occipital lobe epilepsy from a migraine with aura, a routine EEG may be beneficial in addition to neuroimaging.

Migraine With Aura Treatment

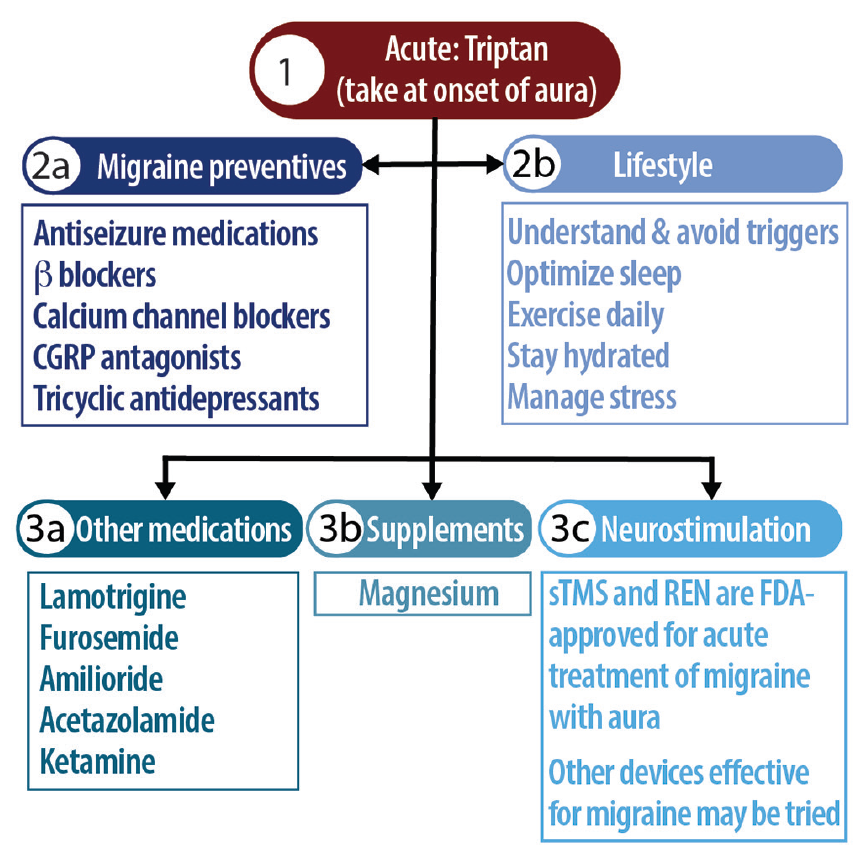

In general, migraine with aura is treated with the same medications as migraine without aura as described in the recent consensus statement from the AHS.22 Acutely, the general recommendation from multiple international headache collaborations is for persons with migraine with aura to take triptans at the onset of aura or any pain,23 even though triptans have been found less effective for migraine with aura compared with migraine without aura.3 Nonpharmacologic options for treatment of migraine without aura include the single pulse transcranial magnetic stimulator or the remote electric neuromodulator, which should be used within 1 to 2 hours of aura onset.24,25 Figure 3 provides an approach to treatment.

Migraine with aura and migraine without aura are distinct disorders that may coexist in the same individual, with important differences (eg, inheritance, risk factors, disease associations, and likely physiology). Continued research into possible pharmaceuticals that can target aura-specific neuronal substrates affecting the triggers of CSD is needed. Such treatments could potentially disrupt aura progression and stop propagation into further phases of a migraine attack, with the hope of reducing migraine disability through treatment of the acute attack and reduction of associated risks (eg, vascular disease).3,22

There is insufficient evidence to suggest patients with migraine with aura should be offered unique treatments that vary from those established in society guidelines as first-line options for migraine, however off-label treatment are often tried.

Various prophylactic treatments outside of guideline-based therapies have been considered for migraine with aura, including lamotrigine,26 which is thought to act on CSD by glutamatergic inhibition but remains classified as “probably ineffective” by the AHS22; furosemide, found in animal studies to act on potassium channels27; or amiloride, thought to inhibit CSD by inhibiting epithelial sodium channels and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP).28 Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor has demonstrated benefit for a rare type of migraine with nonvisual aura, familial hemiplegic migraine, and has been tried for migraine aura status in case studies.29 Ketamine and magnesium have also been explored, and are also thought to act via glutamatergic inhibition; studies to date have shown reduced aura severity but not duration with intranasal ketamine. Magnesium has shown conflicting results for reducing aura symptoms.

Visual Snow Syndrome

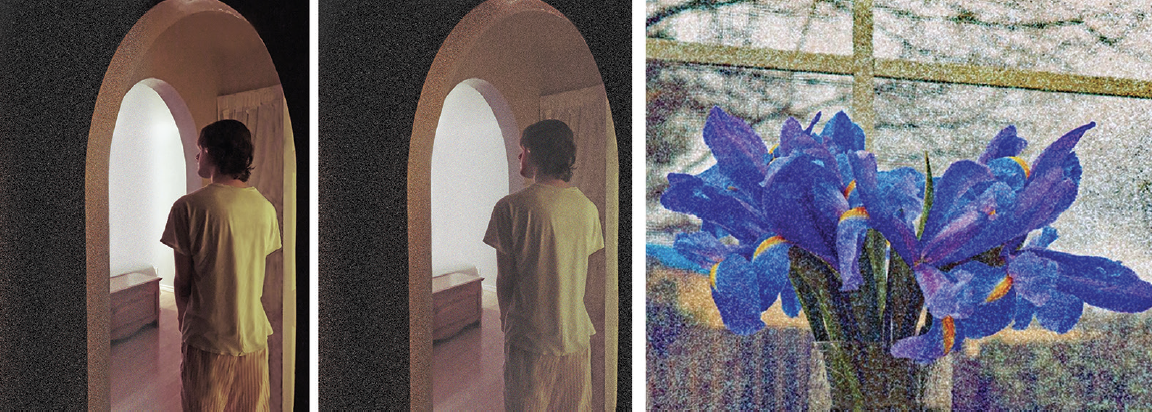

VSS describes a unique presentation of visual impairments associated with migraine but distinct from visual aura and defined as a separate diagnosis under complications of migraine. VSS occurs in up to 2.2% of the population and is more severe and prevalent in people with coexisting migraine with aura.30,31 Persons with VSS experience full visual field disturbances involving millions of tiny dynamic dots, sometimes described as resembling static or snow, or a description comparable to an “analog television,” uniquely presenting without visual defects or changes in acuity (Figure 4).32 Frequently, floaters and afterimages that appear as shadows, sometimes described as “bubbles” or “a carpet background,” are described (Table 1).33

Figure 4. Same World Different View by Monique and Dustin Richardson (left, middle) is an artistic representation of the visual snow phenomenon, displaying variable shading and gradients that can occur. The contrast between panels is meant to show how visual snow affects the same setting: light and colors may be impacted nonuniformly with intense or dark alterations in certain spots, as shown over the human figure appearing clearer (left) or there may be uniform changes to the visual field (middle). How Everything Looks, by Monique Rardin Richardson (right) shows an artistic representation of how irises look during visual snow phenomena.

Images reproduced with permission from the artists.

People with VSS also often experience a constellation of other symptoms including palinopsia, photophobia, enhanced entoptic phenomena, headaches, nyctalopia, bilateral tinnitus, dizziness, afterimages that can appear as diplopia, and fine tremors, notably without the classic diagnostic features of migraine (Table 2).31,32,34 VSS is also associated with other comorbid conditions (eg, migraine, fibromyalgia, and centralized pain disorder. The diagnostic criteria for VSS has been included in the appendix of the ICHD-3, under complications of migraine.35 VSS is defined as 3 months of full visual field infiltration with tiny dynamic spectacles, in addition to 2 of the 4 associated symptoms of palinopsia, enhanced entoptic phenomena, photophobia, or nyctalopia, which are not typical of migraine with aura.33,36

VSS symptoms interfere with the entire visual field, suggesting localization to a central disruption.30 The underlying physiology of VSS is as yet unknown, but neurophysiologic and neuroimaging studies continue advancing understanding of this syndrome. It is theorized that VSS arises from cortical hyperexcitability at the visual cortex and dysfunctional visual processing at the thalamus and striate cortex, likely allowing for subthreshold stimuli processing.34,36 The overlapping visual features of VSS and visual auras suggest a likely common pathophysiology (eg, heightened sensitivity and an impairment to the filtering of sensory input).36

When considering a diagnosis of VSS, clinicians should obtain thorough social and substance use history as well as ophthalmologic and neurologic testing to rule out possible secondary triggers (eg, infection, illness, or head injury).34 Use of tinted glasses, visual filters, and visual therapy is the most efficacious treatment available for VSS, although the resolution of symptoms is unlikely.34,37,38 There remains no consensus on pharmaceutical treatments for VSS, but some studies have shown symptomatic benefit with lamotrigine, sertraline, topiramate, verapamil, and acetazolamide.37 Considering that 52% to 72% of people with VSS also meet diagnostic criteria for migraine, treatments for migraine are frequently recommended. Preventive migraine therapies, however, as well as antidepressants and other pain medications have inconsistently demonstrated improvement of VSS, and some acute treatments, specifically triptans, have worsened VSS in some cases.6,32,37

Alice in Wonderland Syndrome

“Self-experienced paroxysmal body image illusions involving distortions of the size, mass, or shape … often occurring with depersonalization and derealization.”39

A fantastical visual phenomenon associated with migraine is the AWS, also known as the eponymous Todd syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by visual distortions of one’s own body size and occurs most commonly in children and adolescents.39,40 Frequently described symptoms of AWS include micropsia, teleopsia, macropsia, and metamporphasia.41 Various case reports indicate symptoms typically last several days, and only on rare occasions continue for months.39 Considering the unique visual perceptions and body schema symptoms involved with this syndrome, it remains clinically important to distinguish the visual symptoms of AWS from hallucinations and illusions and even hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, triggered by substance use.39

Although the pathophysiology of AWS is unknown, there appears to be a likely association with migraine, viral infections, and seizure disorders.40 AWS has been associated with a wide variety of other conditions, including eye disorders, psychiatric conditions, medications, substance use, ear dysfunction, and even some case reports of vestibular migraine and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.39 It has been estimated that 33% of children without a history of migraine at time of AWS diagnosis go on to develop migraine.42 Although often unrevealing, investigations with EEG and brain MRI may be considered if additional neurologic signs indicate further workup is warranted or symptoms are persistent. There are no proven treatments for AWS and clinicians should focus on treating any associated conditions and providing reassurance for spontaneous remission.35

Conclusion

Our knowledge of the intricate relationship between migraine and vision continues to evolve. The high incidence of visual aura associated vascular comorbidities and growing recognition of other visual syndromes such as retinal migraine, VSS, and AWS illustrate the topic’s importance for practicing clinicians. Despite the common pathophysiology involving CSD, migraine with aura should be viewed as a distinct disorder from migraine without aura, At this time, there are no unique pharmacologic agents specifically approved by the FDA for visual aura, VSS, or AWS. Treatment options remain comparable to those established for migraine (for persons with concurrent migraine), with some smaller studies offering alternative suggestions for visual aura and VSS. It is prudent that practicing neurologists understand the presentation, symptoms, associated risk factors and underlying physiology of aura, as well as the other visual syndromes associated with headache, distinctly from migraine without aura or other neurologic conditions. Appropriate diagnosis, treatment, and risk factor modification assist in relieving discomfort and enabling longevity.

1. Michiana Eye Center. “Oh no, not another!” Aura migraines and artistic expression. August 28, 2017. Accessed March 11, 2022. http://www.michianaeye.com/blog/85566-oh-no-not-another-aura-migraines-and-artistic-expression

2. Smith SV. Neuro-ophthalmic symptoms of primary headache disorders: why the patient with headache may present to neuro-ophthalmology. J Neuro-ophthalmol. 2019;39(2):200-207.

3. Hansen JM, Charles A. Differences in treatment response between migraine with aura and migraine without aura: lessons from clinical practice and RCTs. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):96.

4. International Headache Society. IHS Classification ICHD-3: H. 1.2 Migraine with aura. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://ichd-3.org/1-migraine/1-2-migraine-with-aura/

5. Viana M, Tronvik EA, Do TP, Zecca C, Hougaard A. Clinical features of visual migraine aura: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):64.

6. Evans RW. The clinical features of migraine with and without aura. Pract Neurol (US). 2014;13:26-32. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2014-apr/the-clinical-features-of-migraine-with-and-without-aura

7. Marzoli SB, Criscuoli A. The role of visual system in migraine. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(1):99-102.

8. Kurth T, Chabriat H, Bousser MG. Migraine and stroke: a complex association with clinical implications [published correction appears in Lancet Neurol. 2012 Feb;11(2):125]. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(1):92-100. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70266-6

9. Kim KM, Kim BK, Lee W, Hwang H, Heo K, Chu MK. Prevalence and impact of visual aura in migraine and probable migraine: a population study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):426.

10. International Headache Society. IHS Classification ICHD-3: H. 1.2.1.2 Typical aura without headache. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://ichd-3.org/1-migraine/1-2-migraine-with-aura/1-2-1-migraine-with-typical-aura/1-2-1-2-typical-aura-without-headache/

11. International Headache Society. IHS Classification ICHD-3: A1.4.5 Migraine aura status. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://ichd-3.org/appendix/a1-migraine/a1-4-complications-of-migraine/a1-4-5-migraine-aura-status/

12. International Headache Society. IHS Classification ICHD-3: 1.4.2 Persistent aura without infarction. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://ichd-3.org/1-migraine/1-4-complications-of-migraine/1-4-2-persistent-aura-without-infarction-2/

13. Cologno D, Torelli P, Cademartiri C, Manzoni GC. A prospective study of migraine with aura attacks in a headache clinic population. Cephalalgia. 2000;20(10):925-930.

14. Sen S, Androulakis XM, Duda V, et al. Migraine with visual aura is a risk factor for incident atrial fibrillation: a cohort study. Neurology. 2018;91(24):e2202-e2210. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006650

15. Mahmoud AN, Mentias A, Elgendy AY, et al. Migraine and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: a meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies including 1 152 407 subjects. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020498. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020498

16. Androulakis XM, Kodumuri N, Giamberardino LD, et al. Ischemic stroke subtypes and migraine with visual aura in the ARIC study. Neurology. 2016;87(24):2527-2532.

17. Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association [published correction appears in Stroke. 2014 Oct;45(10);e214] [published correction appears in Stroke. 2014 May;45(5):e95]. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1545-1588. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000442009.06663.48

18. Tzourio C, Tehindrazanarivelo A, Iglésias S, et al. Case-control study of migraine and risk of ischaemic stroke in young women. BMJ. 1995;310(6983):830-833.

19. Diener HC. The risks or lack there of migraine treatments in vascular disease. Headache. 2020;60(3):649-653.

20. Champaloux SW, Tepper NK, Monsour M, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with migraines and risk of ischemic stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(5):489.e1-489.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.019

21. Sacco S, Merki-Feld GS, Ægidius KL, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC) [published correction appears in J Headache Pain. 2018 Sep 10;19(1):81]. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):108. Published 2017 Oct 30. doi:10.1186/s10194-017-0815-1

22. Ailani J, Burch RC, Robbins MS; Board of Directors of the American Headache Society. The American Headache Society Consensus Statement: update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2021;61(7):1021-1039.

23. Worthington I, Pringsheim T, Gawel MJ, et al. Canadian Headache Society Guideline: acute drug therapy for migraine headache. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(5 Suppl 3):S1-S80.

24. Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, et al. Single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation for acute treatment of migraine with aura: a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(4):373-380.

25. Yarnitsky D, Dodick DW, Grosberg BM, et al. Remote electrical neuromodulation (REN) relieves acute migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Headache. 2019;59(8):1240-1252.

26. Buch D, Chabriat H. Lamotrigine in the prevention of migraine with aura: a narrative review. Headache. 2019;59(8):1187-1197.

27. Rozen TD. Treatment of a prolonged migrainous aura with intravenous furosemide. Neurology. 2000;55(5):732.

28. Holland PR, Akerman S, Andreou AP, Karsan N, Wemmie JA, Goadsby PJ. Acid-sensing ion channel 1: a novel therapeutic target for migraine with aura. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(4):559-563.

29. Haan J, Sluis P, Sluis LH, Ferrari MD. Acetazolamide treatment for migraine aura status. Neurology. 2000;55(10):1588-1589.

30. Klein A, Schankin CJ. Visual snow syndrome as a network disorder: a systematic review. Front Neurol. 2021;12:724072. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.724072

31. Schankin CJ, Maniyar FH, Sprenger T, Chou DE, Eller M, Goadsby PJ. The relation between migraine, typical migraine aura and “visual snow.” [published correction appears in Headache. 2015 Apr;55(4):592]. Headache. 2014;54(6):957-966. doi:10.1111/head.12378

32. Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic Minute: Visual Snow. 2021. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISYJ5zoH9Ng

33. Metzler AI, Robertson CE. Visual snow syndrome: proposed criteria, clinical implications, and pathophysiology. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18(8):52.

34. Puledda F, Schankin C, Digre K, Goadsby PJ. Visual snow syndrome: what we know so far. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018;31(1):52-58.

35. International Headache Society. IHS Classification ICHD-3: A1.4.6 Visual snow. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://ichd-3.org/appendix/a1-migraine/a1-4-complications-of-migraine/a1-4-6-visual-snow/

36. Lauschke JL, Plant GT, Fraser CL. Visual snow: a thalamocortical dysrhythmia of the visual pathway?. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;28:123-127.

37. Eren O, Schankin CJ. Insights into pathophysiology and treatment of visual snow syndrome: a systematic review. Prog Brain Res. 2020;255:311-326.

38. Unal-Cevik I, Yildiz FG. Visual snow in migraine with aura: further characterization by brain imaging, electrophysiology, and treatment - case report. Headache. 2015;55(10):1436-1441.

39. Todd J. The syndrome of Alice in Wonderland. Can Med Assoc J. 1955;73(9):701-704.

40. Lanska JR, Lanska DJ. Alice in Wonderland syndrome: somesthetic vs visual perceptual disturbance. Neurology. 2013;80(13):1262-1264.

41. Blom JD. Alice in Wonderland syndrome. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(3):259-270.

42. Liu AM, Liu JG, Liu GW, Liu GT. “Alice in wonderland” syndrome: presenting and follow-up characteristics. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51(3):317-320.

MKJ and AIM report no disclosures