This essay is adapted from Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, out now from Little, Brown.

Child abuse was Edward Gorey’s métier, in a manner of speaking. Gorey, who died in 2000 at 75, was the author and illustrator of a hundred or so little picture books whose pen-and-ink illustrations flawlessly counterfeit Victorian engravings and whose lugubriously amusing nonsense verse, equal parts Edward Lear and Samuel Beckett, spins black comedy from murder, mayhem, and existential malaise. Gorey’s books look at first glance like children’s books, or at least children’s books from the Victorian or Edwardian ages in which they’re often set, and his tongue-in-cheek takeoffs on children’s genres like the Puritan primer or the 19th-century morality tale make them sound like them, too. But as with Beckett’s absurdist tragicomedies, Gorey’s darkly droll tales touch—lightly—on weighty matters: the death of God, the meaning of life, and, always and everywhere, our impending mortality. Emblems of innocence and naïveté, children make perfect victims, as Gorey told the New Yorker. “It’s just so obvious,” he said. “They’re the easiest targets.”

No title epitomizes that point better than The Gashlycrumb Tinies, Gorey’s 1963 parody of abecedaria—ABC books—that uses the deaths of 26 mites as punchlines in life’s existential farce: “E is for Ernest who chocked on a peach/ F is for Fanny sucked dry by a leech … ” It’s Gorey’s best-known book, grist for hipster tattoos and for countless takeoffs, from Mad magazine’s recent “Ghastlygun Tinies,” a pitch-black commentary on school shootings, to a Game of Thrones spoof to the inevitable Harry Potter version (The Hogwarts Tinies) to a Game Over Tinies that casts video game characters like Sonic the Hedgehog and Super Mario Brothers in the roles of the doomed tots. A witheringly satirical version appeared during the 2016 presidential race, The Ghastlytrump Tinies, a nightmare vision of what would happen if Trump won the White House.

Mash-ups and appropriations of The Gashlycrumb Tinies testify to Gorey’s enduring influence on pop culture. If anything, that influence is growing, perhaps because Generation Xers and millennials who discovered Gorey through movies by Tim Burton or books by Neil Gaiman, Lemony Snicket, or Ransom Riggs are now moving the levers of the culture industry. Or maybe it’s because Gorey’s camp-macabre, ironic-gothic outlook—his “mission in life,” he said, was “to make everybody as uneasy as possible … because that’s what the world is like”—seems right for our times. It’s received wisdom among TV producers, for example, that reboots of pop culture flotsam from the Wonder Bread era, such as the new Archie Comics spinoff The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, must be both arch and grim, bled white of all innocence and painted in the gloomy hues of gothic fiction.

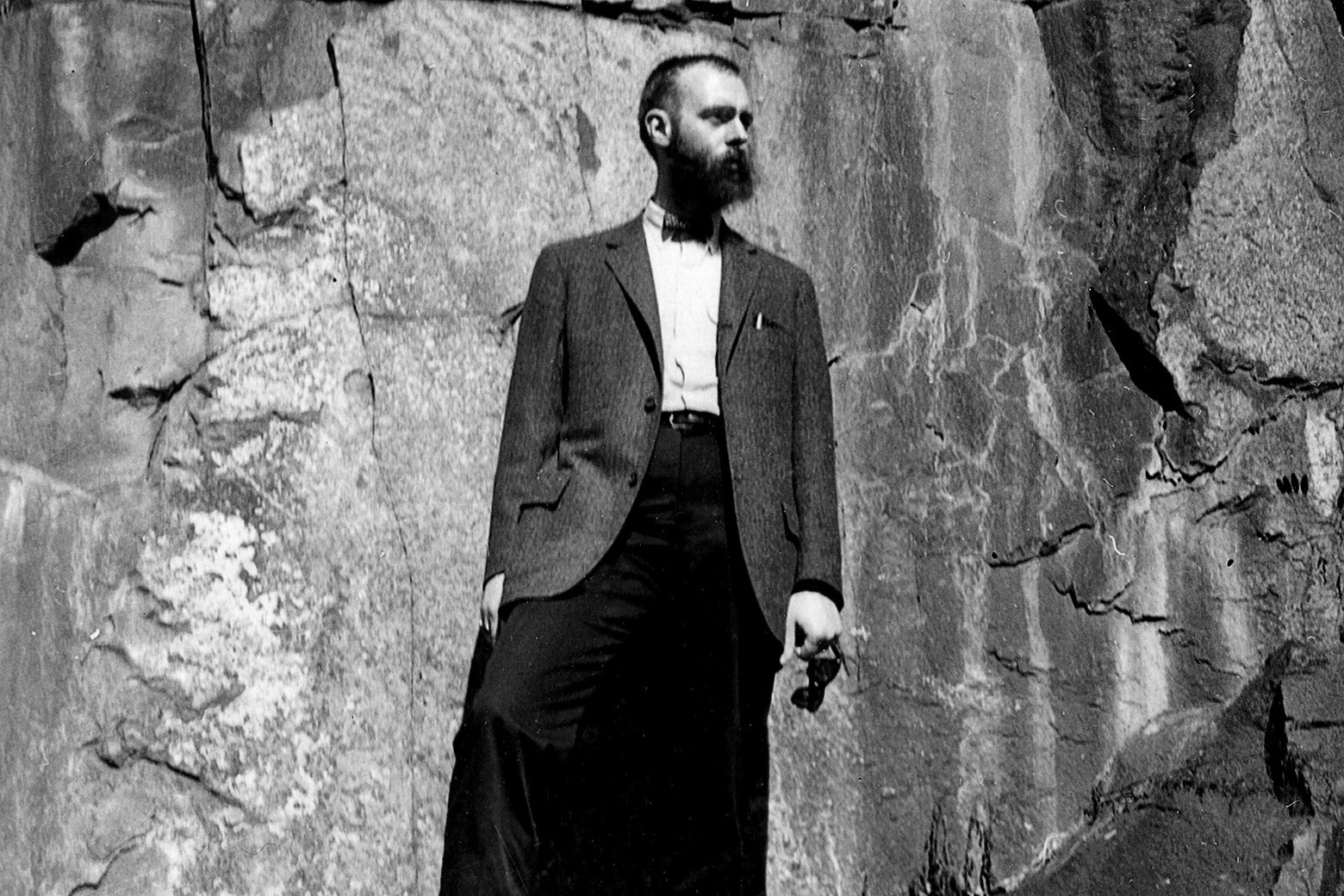

Gorey wrote The Gashlycrumb Tinies at a time when he was in the doldrums professionally if not creatively. He had landed a job at the New York publisher Bobbs-Merrill, where from ’62 through ’63 he spent a dispiriting year as art director. A Wildean aesthete who sported a beard of Old Testament proportions and liked to swan around in floor-length fur coats, Gorey bridled at the stuffy corporate atmosphere and managerial incompetence. (He and his similarly disgruntled coworkers referred to their employer as “Boobs Muddle.”) Happily, he was fired sometime in ’63, “which was just as well,” he later said. “After that I just had too much freelance work to look for another job.” A welcome escape from his workaday grind at Bobbs-Merrill, The Gashlycrumb Tinies anticipated Gorey’s transformation into a full-time author—and auteur of a hilariously bleak vision of the human condition.

The Gashlycrumb Tinies or, After the Outing appeared in 1963, in a boxed set published by Simon & Schuster called The Vinegar Works: Three Volumes of Moral Instruction. It debuted a year after the arrival of Maurice Sendak’s four-volume Nutshell Library. Since he knew Sendak and seemed to have kept abreast of children’s book publishing, it’s unlikely Gorey hadn’t gotten wind of Sendak’s wry take on Puritan primers and Struwwelpeter-type cautionary tales. Whether The Vinegar Works is his response, we don’t know, but the timing is suggestive.

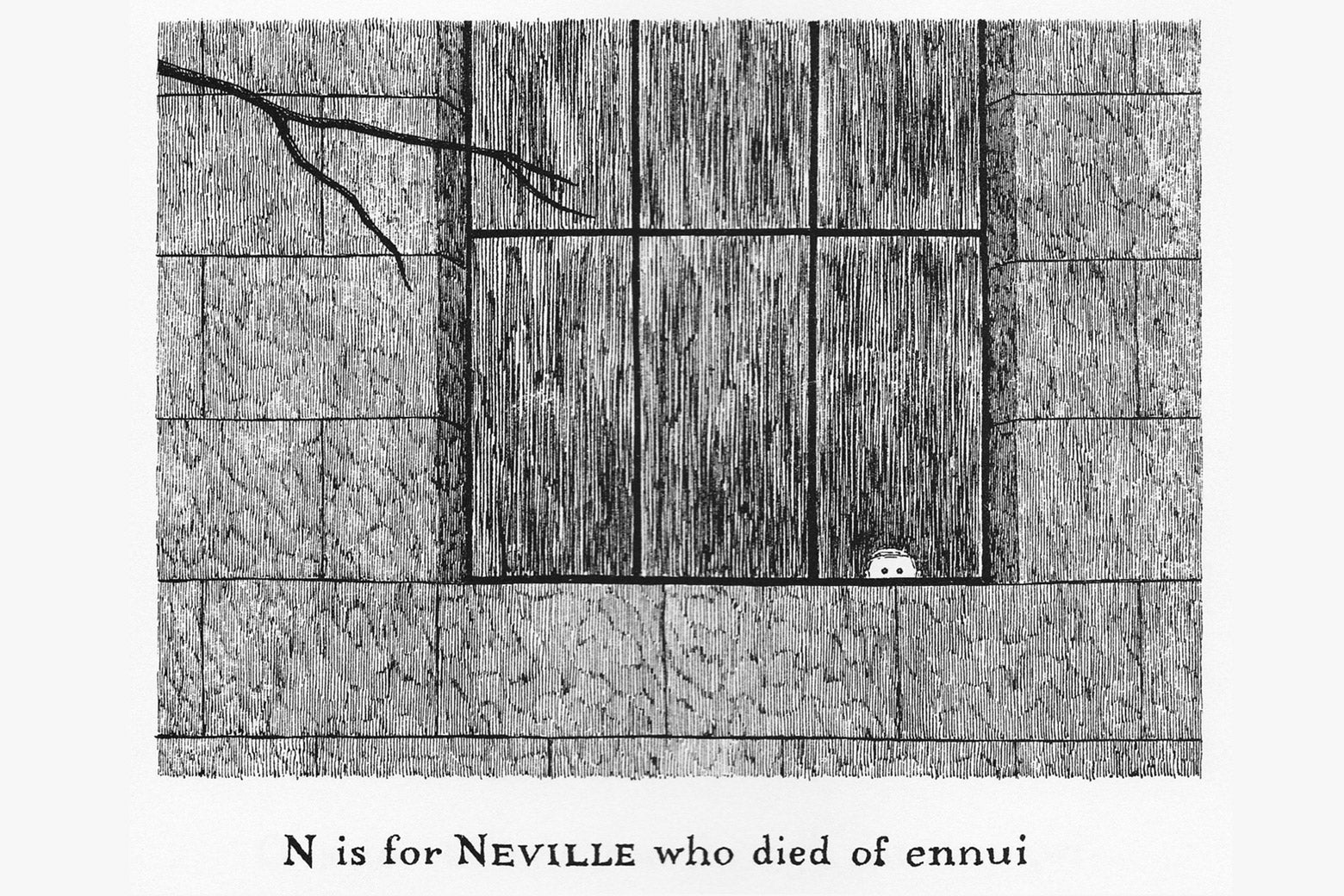

Written in sprightly dactylic couplets, The Gashlycrumb Tinies was inspired, said Gorey, by “those 19th century cautionary tales, I guess, though my book is punishment without misbehavior.” The drawings are wonderful, in their restrained way. Gorey’s compositions, as always, are expertly balanced: He conducts duets between dark or densely patterned shapes and white or gray space, between his little victims and the mostly empty spaces that surround them.

Gorey could be a great single-panel gag artist when he wanted to be. The verse is often uproarious, and the artwork showcases his cartoonist’s gift for illustrating a joke in the most amusing way. “N is for Neville who died of ennui” takes an inherently hilarious notion—expiring from world-weariness, a concept only Gorey could dream up—and makes it even funnier by showing us nothing but the top of Neville’s bored little head, his black-dot eyes peering blankly at us out of an enormous window. (This was one of Gorey’s favorite scenes. When an interviewer noted one of many paradoxes—“He delivers punch lines and sardonic commentary with ease, but rarely laughs”—he observed, “I don’t set out to be funny. Obviously, if I find myself giggling about something, I’ll keep it in. … I must say I did think at the time that ‘N is for Neville who died of ennui’ was rather fetching.”)

Gorey’s ironic distance absolves us of the moral obligation to empathize. It gives us license to chuckle at the messy end we know is in store for the dapper little gent in tweeds, eagerly opening his booby-trapped gift in “T is for Titus who flew into bits.” Sometimes, it’s the cluelessness of the little dears that turns tragedy into slapstick: Why is Olive, in “O is for Olive run through with an awl,” tossing such a nasty implement into the air, to see where it will land? In The Gashlycrumb Tinies, parents are nowhere to be seen, leaving children to their fates, which, nine times out of 10, the little ninnyhammers richly deserve.

Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey

By Mark Dery. Little, Brown.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Actually, there is one parental figure in the book. The cover illustration depicts Death as a skeletal nanny, surrounded by his charges. Like the child-snatching bogeyman of every parent’s worst nightmares, Death is only posing as the Tinies’ guardian. The book’s back cover reveals their fate: a cluster of headstones huddles where the children stood. This, presumably, is what happened “after the outing.” Death is ever-present, even in the coziest domestic settings, just waiting for one dumb move (say, swallowing tacks), a freak accident (suffocating under a rug), an act of God (managing, somehow, to be devoured by mice). And it doesn’t make exceptions for youth or cuteness.

The Gashlycrumb Tinies broaches the subject of death in a children’s book, or at least in what looks like a children’s book. And it did so at a time when the Little Golden Books that dominated kinderculture were serving up a steady diet of treacle and mush. Seen in that light, it really does offer moral instruction, after all. Gorey’s gift to his youngest readers is a book of ABCs that uses a variation on that schoolyard staple, the dead-baby joke, to teach them that death is part of life. “When you were a child, would you have relished The Gashlycrumb Tinies?” an interviewer asked. “Probably, yes,” was his predictable reply.