Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Excerpted from The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2022 by Isaac Butler.

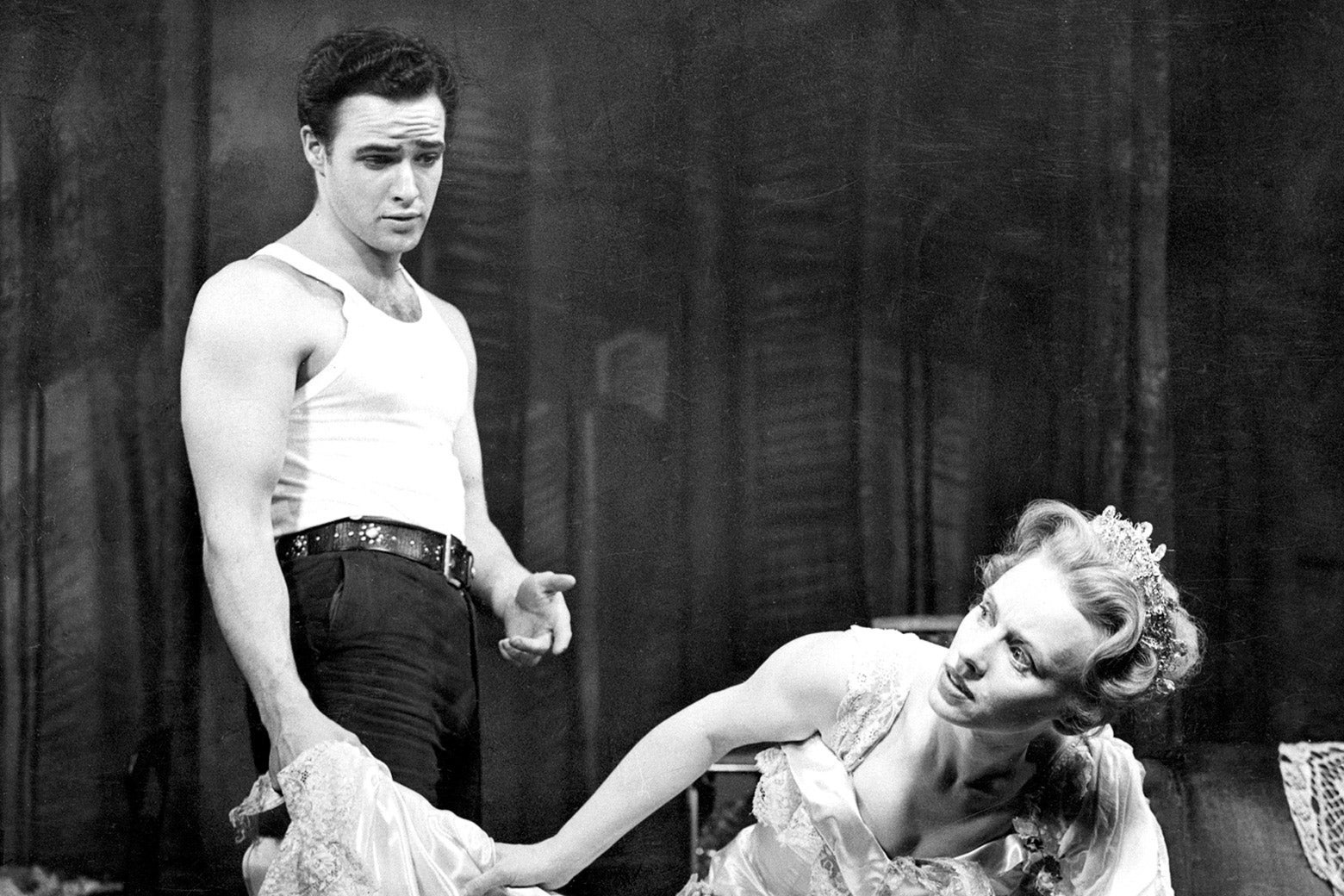

Marlon Brando was cast in Streetcar almost against his will, and he was not the first choice for the role of Stanley Kowalski. Originally, producer Irene Selznick had wanted John Garfield for the part, but negotiations broke down over Garfield’s demand to be cast in any future film of the play and his refusal to commit to a long stage run. Bill Liebling, an agent whose wife, Audrey Wood, represented Tennessee Williams, thought Brando was perfect for the part of Stanley but couldn’t reach him to tell him to audition. By the summer of 1947, Brando had drifted away from acting after being fired from a Tallulah Bankhead vehicle. He didn’t have a phone or an easy way to be reached.

Liebling had to put the word out on the street, telling everyone he knew that if they happened to run into Brando, they should tell him to call the office. On Aug. 20, Brando finally auditioned for Elia Kazan, who immediately knew he was right for the role. Irene Selznick, however, was still hopeful they could get Garfield or, failing him, someone else famous. Williams’ last play, The Glass Menagerie, had been a hit, but Streetcar was still a risk. A name star would make the show a surer thing. Besides, wasn’t this kid too young for the part? Kazan persisted. Selznick agreed to cast Brando, but only if they could get him to audition for Williams at the playwright’s house in Provincetown. Brando told Kazan he had no money to make the trip. Kazan gave the young actor bus fare and told Williams to expect him.

Brando was always irresponsible, but his irresponsibility reached spectacular heights when he was ambivalent and conflicted, as he was about both acting and the role of Stanley Kowalski. He’d been mistreated by Tallulah Bankhead, mistreated by acting teacher and director Erwin Piscator, who had demanded an obedience from Brando that he was incapable of giving when he was a student, and mistreated by his father, whom Stanley resembled in more ways than one. Did he want to do this? Did the ever-restless Brando want to commit to doing the same thing eight times a week for the foreseeable future? While he tried to figure that out, he spent Kazan’s bus fare on supplies for a party at the apartment of his friend Maureen Stapleton.

When a week went by and Kazan hadn’t heard anything, he phoned Williams, only to learn that Brando had never shown up. At that moment, Marlon was hitchhiking to Provincetown. There, he met up with Ellen Adler—daughter of his acting mentor Stella Adler, and his former lover— and trudged over to Williams’ house. When he arrived, Williams and his friends were sitting in the dark, occasionally getting up to pee in the woods. A fuse had blown, the toilet was broken, and the house was full of artists who had no idea how to fix either. Marlon quickly repaired both toilet and fuse, wowing the assembled guests. “He was just about the best-looking young man I’ve ever seen,” Williams said. That night, Marlon read the role for Tennessee, who could see, moments after Brando started talking, that they had found their Stanley.

Soon all of America would see what Williams saw in Marlon Brando, and would embrace both him and the strange new kind of acting he embodied. This new way of performing was remarkably suited to a style of playwriting that emerged alongside it. As Brooks Atkinson described it, “There had been a latent feeling after World War I that something could be done to solve the problems of human existence rationally.” In the interwar years, dramatists like Clifford Odets, Thornton Wilder, and Robert Sherwood had channeled this optimism into their work, only to watch, aghast, as the problems of the ’30s were “concluded … by the desperate organization of the nation into a war machine to produce goods and armies to kill human beings.”

A new darkness entered American drama in response. During World War I, plays about the military had been, in Atkinson’s formulation, “fond propaganda.” During World War II, however, Americans wrote plays like Arthur Laurents’ Home of the Brave, a difficult drama about a Jewish soldier’s survival guilt, or John Patrick’s The Hasty Heart, about wounded servicemen in Burma. Even John Van Druten’s smash romantic comedy The Voice of the Turtle, about a jilted actress who begins a romance with a soldier on leave, is shot through with melancholy.

There was lighter fare to be found—Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit, Mary Chase’s Harvey, and Garson Kanin’s Born Yesterday joined revivals of The Front Page and Lady Windermere’s Fan—but serious American drama had only gotten more pessimistic. It also turned inward, the same direction in which American acting increasingly pointed. The end of World War II did nothing to abate this pirouette toward darker, more introspective territories. Anxiety over what the war had done to the human soul found its way both into film noir and into Arthur Miller’s searing Ibsenian drama All My Sons, which portrayed the ideal small-town American family as a mirage hiding war profiteering and corruption. The 1946–47 season in which All My Sons premiered on Broadway also included Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, a play whose characters fritter their lives away in an alcoholic haze, prisoners of empty lies and pointless dreams.

With The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire, Tennessee Williams both cemented his place as one of the most significant playwrights of the 20th century and pushed modern drama into ever more troubling ambiguities. Williams, one of the great modern playwrights, crafted plays whose problems were unsolvable in part because the characters’ inner conflicts cannot be resolved. There had been hints of this irresolvable quality in Ibsen, and Strindberg, and Chekhov, but Williams pushed it even further. In The Glass Menagerie, Amanda Wingfield wants her daughter, Laura, to be self-sufficient, but she is also the reason Laura will never be able to take care of herself. Menagerie is a memory play that leaves the audience as haunted as Tom, its narrator and protagonist, who is as powerless to change the events of the past as Amanda and Laura are to change themselves. In A Streetcar Named Desire, Williams presents a domestic nightmare and refuses to take sides between its characters, denying his audience the safety valve of moral indignation.

Streetcar needs a sense of truth from its performers to balance out the characters’ lies and delusions. It demands from actors an ability to deliver Williams’ heightened, highly poetic dialogue like everyday speech, and to portray his astounding, complex characters as though they were people—not types, or heroes, or victims, or monsters, but people. Actors had to find, as Stanislavski had always taught, the opposites within the characters. The charm that made Stanley so seductive, the backbone that made Blanche so formidable, the need that so confused Stella’s sense of right and wrong. Clifford Odets may have been the first Method playwright, but Williams gave America its first indelible Method characters.

A profile of Kazan in the New York Times written during Streetcar’s rehearsals in November 1947 shows how much of the method had already permeated the theatrical mainstream, and how much was left to go. Reporter Murray Schumach was particularly struck by Kazan’s passion for script analysis, for the way in which his process relied not on intuition and inspiration but on his intellect. “Even Kazan’s admirers,” he wrote, “stand a little in awe of his fanatical devotion to pure reason in art. What, then, is Kazan’s method and how does it function in a field where logic is supposed to be confined to the box office?” Answering this question took Schumach on a tour of basic Stanislavskian concepts, including the spine, the beat, the throughline of action, and subtext. Kazan wanted actors who had “the ability to understand not only the lines but the reasons for those lines,” what the Group Theatre would have called their problems and what An Actor Prepares called their objectives. In 1947 these were no longer incomprehensible foreign concepts. They were now the secret tricks of the trade’s best director. Soon, in part because of Kazan, they would become the cornerstones of American acting.

In rehearsals, Kazan worked to bring Brando out of his shell, and to keep co-star Jessica Tandy from killing him. Tandy, who played Blanche, was the consummate professional actor. She made her stage debut in her native London at the age of 18 in 1927. She had played Ophelia opposite John Gielgud and Katherine opposite Laurence Olivier’s Henry V. Brando’s behavior in rehearsal infuriated Tandy. He rarely arrived on time and, likely because of his dyslexia, had difficulty memorizing his lines. She was not alone in her annoyance. Karl Malden, who played Mitch, found Brando’s luxurious pauses so grating that he lost his temper in rehearsals. “Who the hell can get anything done around here?” he said. “There’s no rhythm to the scene. One day you’re too early, the next you don’t come in at all!”

Brando refused to abide by one of the basic demands of professionalism in theater: that you must freeze your performance so that it remains close to identical night after night. There are commercial reasons for doing this—it ensures that the consumer gets a product whose quality is certified—but there are artistic ones as well. Change your timing, and the whole carefully worked-out staging of a scene might go awry. Change your performance, and your scene partner has to adjust on the fly to accommodate you. As Malden put it, “I like to be cooperative in a scene, to help someone deliver in any way I can. Marlon’s attitude was very much, ‘This is how I’m going to play this scene today. I may play it differently tomorrow. You have to figure out what you’re doing yourself.’ ” Kazan felt powerless to stop his mercurial leading man and, like Stanislavski and Strasberg before him, was struck dumb in the presence of an actor experiencing the role as he played it. “Marlon was living on stage. … A performance miracle was in the making. What was there to do but be grateful?” Malden, despite his reservations, agreed. “I believe playing with Marlon consistently brought out the best in me,” he wrote. “I guess, in the final analysis, it is impossible to beat genius, but it can be great fun to try to match it.”

To Tandy, however, Brando was “an impossible, psychopathic bastard.” Both Kazan and Brando felt that Tandy’s anger arose from envy. Audiences at the show’s out-of-town tryouts were coming to side with Brando, and thus with Stanley, against both Tandy and Blanche. “I think Jessica could have made Blanche a truly pathetic person, but she was too shrill to elicit the sympathy and pity the woman deserved,” Brando later said. “I didn’t try to make Stanley funny. People simply laughed, and Jessica was furious because of this, so angry that she asked Gadge [a nickname for Kazan] to fix it somehow, which he never did.”

The person who asked Kazan to step in was actually Hume Cronyn, Tandy’s husband and Kazan’s close friend. According to Kazan, what Cronyn asked the director to fix was his wife’s performance. “She can do better,” he told Kazan during an early run-through. “Don’t give up on her.” The problem, as both Cronyn and Kazan saw it, was that Tandy’s carefully worked-out performance could not match Brando’s lightning strike of inspiration. Audiences could feel this; they were drawn to him and would stay with him even as Stanley was revealed to be a wife beater and a rapist. This isn’t what Kazan wanted. He wanted the audience to begin the play siding with Stanley over Blanche and then come to see the assumptions that had led them to that sympathy as it curdled. Streetcar devastated you not only because you have watched the destruction of Blanche DuBois but because you, sitting in your chair in the dark, realize your own emotional complicity in her downfall.

Kazan didn’t know how to solve this problem. He couldn’t tell Brando to be less good, and he couldn’t explain it to Tandy or she might choke. He brought the issue to Williams instead, only to learn that Williams didn’t see it as a problem. “When you begin to arrange the action to make a thematic point,” he told Kazan, “the fidelity to life will suffer. … Marlon is a genius, but she’s a worker and she will get better. And better.”

Williams was right. By the time Streetcar opened on Dec. 3, 1947, the entire cast had risen to the occasion. Brooks Atkinson’s review in the New York Times is full of effusive praise for Tandy. She was by far the biggest name in the production, and Atkinson treats the play as if it were a vehicle for her, mentioning Brando only in an aside about the “rest of the acting” in the show being “of very high quality indeed.” The rave reviews for the play helped it run for two profitable years alongside a national touring production.

The relationship between the show’s leads, however, remained as rough as ever. During rehearsals for Streetcar, Brando had attempted to smooth things over with an apology to Tandy. But he bungled it somehow, leading to an exchange of letters between the two actors. “I was aware that my apology to you was insufficient to an obvious degree,” Brando wrote. “When I am confronted with a situation wherein I feel compelled to express my feelings directly, I am not surprised to find my mouth full of stones. … In order to alleviate my embarrassment, I hide feelings in an attitude which, understandably, might be misinterpreted as impertinence.” But he wanted her to know he was sorry, and he was also grateful for her “gracious behavior to my ungraciousness.”

Several weeks later, with the show already open, Tandy decided to tell Brando some things for his own good. She warned him that his behavior was “bound to hurt you eventually and earn you a reputation for irresponsibility which I don’t think managers or directors will tolerate, despite your unusual abilities.” Yes, he was talented, but talent got actors only so far. It could “mean a great deal to you in the theatre—but only if you are prepared to enhance it, to work with it, to take the trouble to control it. If you won’t learn to do these things, it will go down the drain.” Brando had the potential to be a great force for good in the theater, but only if he had the discipline and responsibility to improve his behavior and take charge of his career so that he could dictate what plays he would do with whom, and lead their casts by example.

The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act

By Isaac Butler. Bloomsbury.

Brando needed to have proper diction, she wrote, and to say the lines as written while obeying the author’s style, not his own. A great stage actor must be able to perform “Shakespeare, Sheridan, Goldoni or, perhaps, Euripides. All these authors have a style of their own, and it is my belief that an actor has no right to impose his personality and style on the author’s work.” With finely honed condescension, Tandy tells Brando that he has enormous gifts, and that “perhaps this [letter] will give you more assurance so that you will be able to tackle your faults without being depressed by them.”

As an English actor, Tandy wanted Brando to reform himself in the English tradition, modeling his future self on Laurence Olivier. Her letter clearly sets out the divide between classically trained English actors and their more inward-focused cousins across the Atlantic. Over the years to come, Olivier would become the Method’s foil in the public eye, the epitome of the English approach, one that was largely external, based on physical and vocal transformation and careful attention to the rhythms and sounds of the text. Brando, meanwhile, would become the symbol of the Americans: authentic, unpredictable, interior, and drawn from the self. This conflict between Brando and Tandy, America and England, is also the conflict between Stanley and Blanche. Blanche is all artifice. She describes Stanley derisively as “simple, straightforward, and honest.” Later, Blanche declares, “I don’t want realism, I want magic!” By the end of the play, in a prophecy of things to come for the Method, Blanche has discovered that her artifice doesn’t work as well as she thinks it does, while the audience has discovered that Stanley’s authenticity is another kind of veneer.