It was one of the signature moments of the environmental movement, and one of the turning points of global history. A few long-haired men and women afloat in small rubber inflatables on an open ocean faced a gigantic Soviet whaleship, the Dal’nii Vostok. They positioned themselves next to the panicked groups of sperm whales fleeing the ship, daring the Soviets to fire their harpoons and risk killing the Greenpeace volunteers who had organized and now were filming this dangerous protest. The image was nearly perfectly crafted, as Greenpeace leader Bob Hunter had meant it to be: tiny, helpless individuals pitched against an unfathomably evil, inhuman force—sentient humans, united with sentient whales, versus the unthinking machine of modern bureaucracy and militarism. Hunter summed up the contrast with the horrified observation that the whale oil rendered from the whale carcasses being winched up the stern slipway would go to lubricate intercontinental missiles. “It seemed we were staring into the face of a giant robot,” he wrote, whose “particular obscenity” came from the fact that “here was a beast that fed itself through its anus, and it was into this inglorious hole that the last of the world’s whales were vanishing—before our eyes.”

Indeed they were. At that moment, in June 1975, only a fraction of the former population of great whales remained in the world’s oceans, and the Soviet catcher boat was hunting down some of the last of them. Even worse, Hunter and others had only glimpsed the tip of the iceberg. Unbeknownst to the world, the Soviets had been killing tens of thousands more whales than they were reporting to the International Whaling Commission—an illegal and dishonest catch that one writer termed the “most senseless environmental crime of the 20th century.” It was probably also the most sudden revolution the globe’s oceans have ever experienced.

Decades later, when I first read Hunter’s account and saw the powerful pictures of the encounter, I was shaken. Many in the 1970s had the same reaction. Though Greenpeace was not the only organization protesting commercial whaling at the time, its campaign against the Soviets had the single greatest impact on the growing movement to save the whales. The mind bomb Greenpeace released that day eventually helped create enough public pressure to force a global moratorium on commercial whaling beginning in 1986. Millions of global citizens had concluded, rather suddenly, that whales were not monsters, but emotional, intelligent creatures whose destruction was morally abhorrent and signaled deep problems with modern society. They also decided, based on little more than 20 seconds of television footage, that these Soviet whalers were the real monsters.

Like many people in the world, I find the mass slaughter of whales to be heartbreaking, and their saving heroic. Whatever dangers the world’s whales face today from ship noise, ship strikes, and marine pollution, what they encountered in the 20th century was far worse. From 1900 to 1999, humans killed nearly 3 million whales, in every corner of every ocean. Already by the 1970s they had reduced the population of every large species to near extinction. It was, in the estimation of Phillip Clapham, the former head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s lab for cetacean research, the “largest removal of biomass in world history.” It was also the closest thing to genocide we can observe in the history of human relations with their large mammalian relatives. In less than a century, humans transformed the world’s oceans from places that pulsed with living whales, to nearly empty water. The fact that the large whale species survived at all is a miracle, their 20th-century history a testament both to humans’ collective power to destroy, and to reverse course.

I wrote my new book, Red Leviathan: The Secret History of Soviet Whaling, because I think it essential that we understand this remarkable history. And, looking at Greenpeace’s pictures, I realized there was much more to it than the actions of a handful of environmentalists. I wondered, especially, who were these Russians on the other side of the ship’s bow, looking down at the Greenpeace hippies, firing away at the sperm whale mothers and calves in spite of the protesters? Their role in this episode seemed to me nearly as significant as those of the activists. It demanded a better explanation than militarism, mechanism, and evil. But, despite the fact that they killed more whales than did any other country after World War II, the Soviet Union’s part in the story has remained entirely hidden. After the Greenpeace encounter, the Dal’nii Vostok made its way back to its home port of Vladivostok, ventured out a few more times, then called it quits. Silence ensued. Why?

This book answers that and several related questions. Why did the Soviet Union pursue industrial whaling at such a gigantic scale, even as other countries dropped out of an increasingly unprofitable industry? Why did they kill so many whales above the international quotas they had accepted? Did anyone in the USSR care or try to stop this from happening? Were the Soviets at all moved by the Greenpeace protesters that day in 1975? What was it like for the world’s whales to experience such an unremitting slaughter? Thanks to the opening of former Soviet archives and the dedication of whale scientists in piecing together the scale of the Soviet deception, we can now answer some of these questions. The answers help us understand the fate of the world’s whales, of the Soviet Union, and of the central dramas of the 20th century.

During the years of researching this book, I met former Soviet whalers on several occasions. Two encounters stick out in particular. First, on a midsummer’s day in 2016, I joined a group of whalers from Kaliningrad on the Baltic Sea who gather every year at a small city park notable for a large statue of two fighting bulls. The bulls’ testicles are particularly prominent, and they turned the whalers’ conversation to the culinary qualities of whale testes, which were apparently considerable. Even as cloudbursts erupted, the old men basked in the warmth of jokes and their memories of disasters narrowly averted, larger-than-life harpooners, and the comradery of shared hardship.

These men had done well in the Soviet Union. They had survived perestroika and the chaos of the 1990s, if only just. As one whaler explained to me, he had earned good money at whaling, but post-Soviet inflation had destroyed every cent of it. If many now lived in crumbling apartments, they could at least enjoy their grandchildren making modestly successful futures, wealthier than even these ex-whalers had dreamed of becoming. They were gratified, too, by my interest and by the attention of a film crew making a documentary about Soviet whaling. This was the respect they felt they deserved. Why had they become whalers, I asked? The spirit of the sea had lured them, they responded. Some said they had just been born hunters. “Read this book of whaling poetry,” one advised me. “There are more answers to your questions in one verse than in all our responses.”

As the evening inevitably turned to cognac at a nearby Ukrainian restaurant, toasts were offered to “international friendship,” and the surreal nature of the scene stole in through the beginnings of a headache in my mind. Here I was, chatting amicably with men who had played a central role in one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century, whose only reckoning had been the fact that the world had forgotten about them. Others who cared deeply about whales had made darker accusations. As Bob Hunter had asked after his encounter with the Dal’nii Vostok, “What indeed could a nation of armless Buddhas [whales] do against the equivalent of carnivorous Nazis equipped with seagoing tanks and Krupp cannons?” Few today would be willing to go as far as Hunter. The whalers at the table with me had massacred nonhumans, and they had done it at a time when few thought it wrong. At least the outside world had recognized the Nazis’ actions as immoral as they were occurring. Soviet whalers were hardly Nazis.

But that should not keep us from recognizing the scale of the horror that whales experienced during the age of industrial whaling, which spanned nearly the entire 20th century. For whales, what industrial whalers—and the Soviets prominent among them—did was a uniquely terrible chapter in their very long history. Few creatures have enjoyed such long-term security as modern whales, streamlined for quick movement and insulated with blubber to outlast long fasts and migrations. They have nearly no predators except for humans. While Indigenous whalers, Japanese shore whalers, and Western sail whalers in the 19th century had eliminated or seriously reduced local populations—driving Atlantic gray whales into extinction and nearly doing the same to Pacific gray whales and southern right whales—they had left the world’s largest whales almost entirely untouched. At the dawn of the 20th century, the world’s oceans were nearly as full of blue whales, fin whales, humpback whales, and others as they had ever been. The industrial slaughter of the world’s whales takes its place alongside the other unprecedented catastrophes of the 20th century, all of which sit uneasily with the exceptional advances in human knowledge and well-being made during the same time. The Soviet Union was central to many of these stories.

A second meeting with Soviet whalers—this time in Odessa, Ukraine—further complicated my impressions of them. Led by two women who had worked in the whaling industry, a crew of veterans dressed in whaling outfits met my plane at the airport and conducted me on a tour of the former Black Sea whaling capital. Their generosity and amiability were easing me into a sense of familiarity when we sat down at a table at the local military veterans’ administration. The group’s leader started into a speech on the merits of Aleksei Solyanik, the legendary whaling captain who had done so much for the city of Odessa. But before she could really get started, someone interrupted her. I hadn’t realized it, but Yuri Mikhalev, one of the scientists responsible for revealing the shocking scale of Soviet whaling, had joined our group. It was instantly clear that this was going to be a different conversation. Mikhalev began by stating that as a scientist, he had to take a more rational point of view about these things. He was not going to agree with our leaders’ warm words, nor with the golden-hued memories of most of the whalers I had met. Mikhalev began a point-by-point, year-by-year recounting of Solyanik’s lies and misdeeds and their catastrophic effect on Antarctic ecosystems. As he put it elsewhere, “Soviet whaling brought whale populations to near-extinction, was unprofitable, amoral and politically damaging for the country.” Like a scientific Dostoevsky or some such archetypal Russian truth-teller, Mikhalev closed his eyes, concentrating, feeling the pain of each detail, measuring his story with a quiet, deliberate intensity and at the same time an exhausted recognition that nothing could be changed and that similar monstrous actions would likely occur again.

Though I was familiar with the figures Mikhalev was citing, I was still awed by the power of his impromptu speech. It was immediately clear why he had been one of the very few brave enough to say these same things to his superiors and the KGB during the height of the illegal catches. But just as interesting at that moment was the reaction of the men and women at the table. They did not dispute Mikhalev’s tale, nor did they seem angered by this discrediting of their professional lives. Instead, they seized the chance to talk to one of the world’s most knowledgeable cetacean scientists and peppered him with questions about the whales themselves. Why were they found in some places and not others? What explained the quick rebound of some species? Why do whales strand?

I sensed here the troubled heart of my book. I liked these people who had perpetrated one of the greatest ecological catastrophes the world’s oceans have ever seen. I felt a respect for the fact that whaling had given their lives solid, positive meaning. I shared their fascination with whales. But what I perceived as genocide, they thought of simply as work, and I was amazed at how little their recollections included danger or drama. How had such a momentous piece of the globe’s history taken place so routinely, so quietly? Mikhalev, too, presented challenging contradictions. During later conversations with me in his apartment, he described how his protests over illegal whaling had ruined his career. Soviet bureaucrats closed down his biological laboratory, and his health and marriage suffered. But, even with the end of the Soviet Union, Mikhalev had found justice elusive. He, along with fellow scientists Aleksei Yablokov, Viacheslav Zemsky, Alfred Berzin, and Dmitri Tormosov, had revealed to the world the extent of Soviet illegal whaling during the 1990s. He had expected that other former whalers would follow suit. But now, decades later, where were the confessions from the Japanese, who almost certainly were also cheating, or other European countries that Mikhalev suspected as well? What about some reckoning with the hundreds of thousands of whales Americans had killed during the 19th century? Instead of increased openness and mutual understanding, the episode had become another of many in which the West cynically and opportunistically embarrassed Russia. Mikhalev told me he was sure my book would do more of the same.

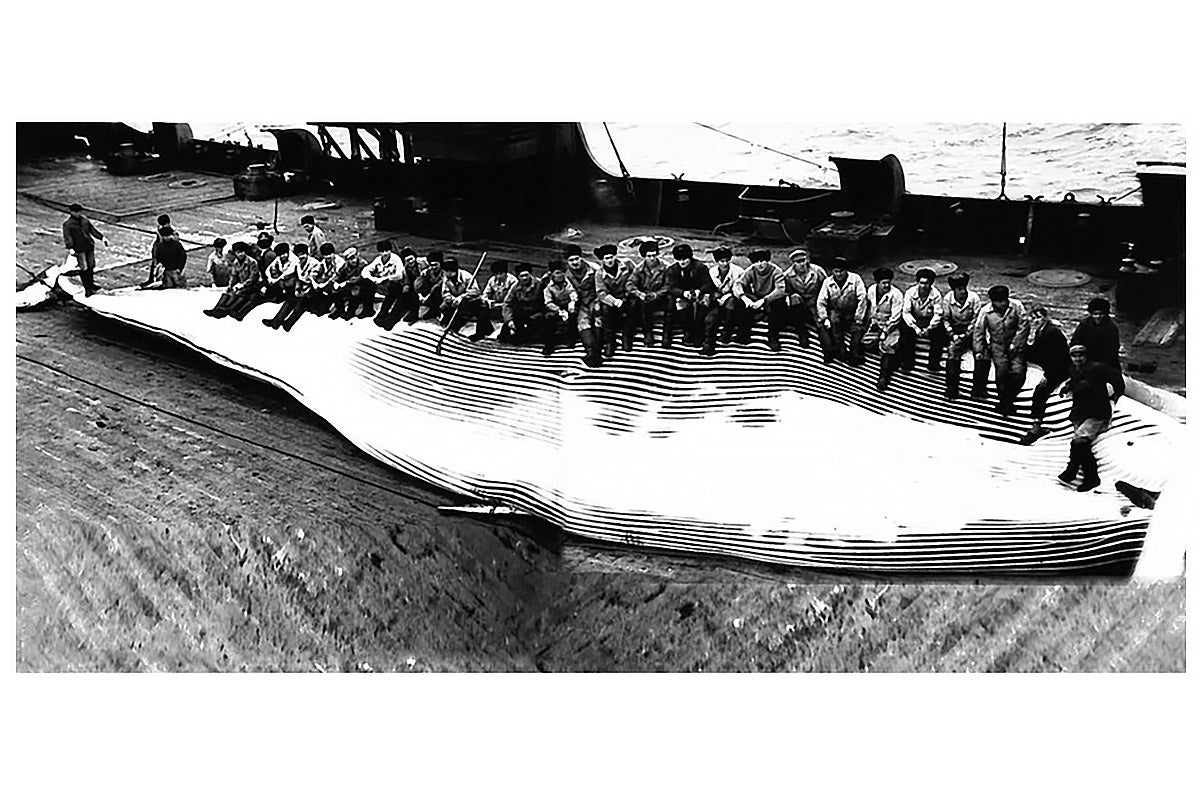

And perhaps it does. I won’t deny that I still find shocking and disturbing the triumphant Soviet documentaries depicting the killing of whale families, the pictures of Soviet whalers taking illegal whales and cavorting over their corpses, or the thousands of pages of archival records dryly documenting a genocide. And, as someone who grew up in Oregon and California in the 1980s, I experienced the ocean at the whales’ lowest point, an ocean that had been created by the Soviet Union as much as anyone. The history of Soviet whaling belongs to anyone who looks out to sea and sees nothing.

But, as Soviet whalers sometimes asked me and others: What is the difference between killing whales and killing, for example, pigs, which so many people accept without a second thought? Or, thinking more historically, why single out the Soviet Union when other countries had in fact killed more whales? It’s true—while the Soviets killed more than 500,000 whales during the 20th century and Great Britain killed more than 300,000, Japan had killed nearly 600,000 and Norway nearly 800,000. Others, mostly American whalers, had killed around 300,000 in the 19th century, at a time when Russians had killed almost none. Australia, Brazil, Canada, Holland, Korea, New Zealand, Peru, South Africa, and others played smaller but still significant roles. Scholars have examined these stories and other critical aspects of humanity’s disastrous relationship with whales in the 20th century. They have shown how the International Whaling Commission failed to head off catastrophic overcatching, and how the preeminent whalers Norway and the United Kingdom gave up on the industry by the early 1960s; have debated why Japan kept whaling through those decades and even past the global moratorium of 1986; and have explained why the science of counting whales became central to changing global ideas about the environment. But, with the exception of biologist Yulia Ivashchenko’s superb research into the industry, and some valuable insights from scholar Bathsheba Demuth, the Soviets, who were crucial to all these developments, have barely been a part of these histories. The result is huge holes in our understanding of why humans nearly destroyed whales and why they stopped just in time.

So, if the Soviet contribution to modern whale genocide was not preeminent, it had special characteristics. The Soviets killed nearly half their whales secretly, in knowing contravention of the conventions they had signed. They did so in the full knowledge of the impact on whale populations. In fact, no one knew the catastrophic state of whale numbers better than Soviet whale scientists, who sailed with the fleets and tallied the destruction. As others exited the whaling industry, the Soviets, alongside the Japanese, helped reduce the world’s whales from imperiled to nearly extinct, doing the hard work of an annihilation that flew in the face of economic rationality. The Soviets were able to do this in part because of a planned economy that resisted market forces. But they also did it for historical reasons that stretched back into earlier eras of global whaling when it was Russians who had been the victims.

Furthermore, behind the ex-whalers’ untroubled 21st-century nostalgia, I discovered a more complex history of relationship with whales. Some Soviet whalers at the time cried when they heard the sounds of the dying animals. Even in this officially atheist state, some felt the weight of sin as they butchered whale families. All knew that what they were doing was illegal, and most knew that extinction was the likely outcome.

These stories also open windows into some neglected but fascinating aspects of Russian history—how Russia has quietly shaped the world’s oceans for a long time; how some of the more obscure parts of the vast Russian Empire, such as Vladivostok and Odessa, were sometimes as important for global history as Moscow and St. Petersburg; how Soviet socialism entertained high hopes of protecting the environment; how Russian scientists made some of the most important contributions to humanity’s understanding of its place in the natural world. These histories get to the heart of what it was like to live and work in the Soviet Union, what it was like to be at the forefront of modern industrialized states’ attack on the ocean, and what it was like to touch and smell huge numbers of large, strange, but strangely familiar marine mammals on a scale few have experienced.

Red Leviathan: The Secret History of Soviet Whaling

By Ryan Tucker Jones. University of Chicago Press.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Finally, my book is about those whales’ lives, too, their cultures, and their families, which were nearly broken by the industrial whalers’ attacks. Their stories cannot be told, either, without the rich data compiled by their killers. The reckless gamble of destroying the world’s whales is entwined with the life of the Soviet Union, the 20th century’s most daring social experiment. The stern slipway—the key technological piece of industrial whaling—was invented in 1922, five years after the Soviet Union’s creation in 1917. The Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, four years after the last whale was killed for commercial purposes. Leviathan was slaughtered in the transiting shadow of the Soviet leviathan’s rise and fall.

So, I hope my book does more than simply condemn, that it provides some understanding of the history of both whales and the Soviet Union. I hope, too, that it offers some light in an otherwise dark tale. Whales did survive, after all, and they are now coming back in every ocean in the world. The Soviets’ role in that outcome, too, should not be ignored. This book finally tells their story, the story of those whalers looking down on the Greenpeace zodiacs in 1975, who appeared to the activists as faceless monsters, and who—in all their gore, glory, and human contradiction—for a moment held the fate of the world’s whales in their hands.

Reprinted with permission from Red Leviathan: The Secret History of Soviet Whaling by Ryan Tucker Jones, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2022 by Ryan Tucker Jones. All rights reserved.