Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Virtual Reality

![René Magritte, La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is Not a Pipe]), 1929, oil on canvas. René Magritte, La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is Not a Pipe]), 1929, oil on canvas.](https://www.artandantiquesmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/201312_magritte_01.jpg)

René Magritte—part magician, part humorist, part realist—is as modern as he’s ever been.

![René Magritte, La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is Not a Pipe]), 1929, oil on canvas.](https://www.artandantiquesmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/201312_magritte_01-300x223.jpg)

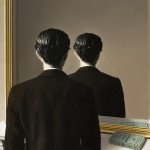

René Magritte, La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is Not a Pipe]), 1929, oil on canvas.

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

- René Magritte, La condition humaine (The Human Condition), 1933, oil on canvas.

- René Magritte, L’assassin menacé (The Menaced Assassin), 1927, oil on canvas;

- René Magritte, La reproduction interdite (Not to be Reproduced), 1937, oil on canvas.

- René Magritte, Les amants (The Lovers), 1928, oil on canvas.

- René Magritte, La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is Not a Pipe]), 1929, oil on canvas.

The Museum of Modern Art has a Tumblr. The social media site allows a user to “curate” and effortlessly share a web page of images, videos or pieces of text, thereby crafting, in a sense, a virtual museum (of course it has more subversive uses as well, but this is a good working definition when it’s being used in the service of one of the most highly respected public art institutions in the world). MoMA isn’t entirely hurting for square footage, but there are perks to sharing images online, especially when your physical walls are installed with a Magritte show (“Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary 1926–1938,” on view through January 14).

Throughout the 20th century, the Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte supplied the advertising industry, other artists and pop culture with bowler hats, black suits and apples ripe for spoofing and reimagining. The iconic green apple in front of the face or the floating bowler—up there with Chaplin’s in its ubiquity—were undoubtedly in any consumer’s consciousness, whether they were aware of Magritte’s name or not. Now, in the age of the Internet, Photoshop, gifs and memes, Magritte’s work has continued to be co-opted, either to sell a product or land a clever joke. MoMA, perfectly aware of this fact, has been blogging gifs and images inspired by Magritte’s work.

Yet despite all of the “this is not a pipe” (a translation of the French sentence painted under a realistic rendering of a pipe in Magritte’s 1929 painting The Treachery of Images) spoofs one can find with a simple Google search or the countless cut-and-pasted cartoon characters in front of cloudy backgrounds with small green objects in front of their faces or the teenage duos taking digital snaps of themselves making out with plastic bags over their faces à la The Lovers (1928), Magritte is still the most clever. This is because his images—Surrealist paintings executed for the most part in the first half of the 20th century—are proto-memes. They bear many of the same compositional elements as the viral imagery that gets passed around the web—deadpan visuals coupled with “it’s not what you think” captions, familiar images being reproduced in unfamiliar settings, a skewed sense of what’s real and/or appropriate and humor as a subversive tool.

But whether or not a comparison between Magritte and LOLCats or Buzzfeed gifs seems far-fetched, what is for certain looking at the artist’s work in 2013—other than the fact that he would be an expert web designer—is that he has had a major effect on modern and postmodern symbology. This was the subject of a recent show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images,” curated by John Baldessari, that took works by Barbara Kruger, Robert Gober and Ed Ruscha and placed them with Magritte’s. His work has helped shape the way we see the blatant and the way we see the illusory.

“His images do get reproduced a lot. The positional strategies get reused. There are even Mario Cart games that have Magritte images,” says Ann Umland, the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Curator of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA and the show’s curator. “With the exhibition we thought, how could we hit refresh? A lot of people know the images because he’s been so appropriated by the advertising industry, but we wanted to take back these images for Magritte, and show people that he’s a Belgian artist from the 20th century, and show people what he was trying to do—how he was remaking the world in terms of dreams.”

The way that MoMA chose to “hit refresh” was by focusing on a very specific period in Magritte’s career, starting in 1926, when the artist first gained recognition as a Surrealist painter in Belgium, and ending a dozen years later, when he delivered a lecture titled “La Ligne de Vie” (Lifeline), shortly before the outbreak of World War II, recounting his work within the Surrealist movement. With some 80 paintings, collages, objects, photographs and periodicals, it is the first exhibition ever to concentrate exclusively on the artist’s early Surrealist work. “What the show has done is to look at his breakthrough years and his engagement with Surrealism, a period that Magritte himself saw as foundational,” says Umland. “I think that what you get when you do a slice of a career like this is the ability to show familiar work and unfamiliar work, and to situate them both in all of the ways that Magritte was working.”

During this early portion of the artist’s career, he develops key aesthetic and conceptual strategies that will remain thematic concerns throughout his oeuvre. He has shifted away from a semi-abstract painting style, discovered and rejected Futurism and studied the work of Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp. He begins to take ordinary objects and re-contextualizes them, in order to, as he puts it, make them “shriek out loud.” He rejects the over-rationalization of consciousness, while also avoiding depictions of incoherent dreamscapes. He begins to play with the relationships between imagery, the visual elements of language, and linguistic meaning. He tugs the viewer through implausible realities like The Cat in the Hat. But maintains a deadpan, straightforward painting style that makes everything seem neat and orderly. Nothing is as it appears, or is it that everything is exactly as it appears?

“In a sense, he is inventing a new sort of figurative painting,” says Umland, “His practice is as reconstructive as Mondrian, in the way that it changes our definition of what a painting is—his paintings are a form of meta-painting. He’s the first conceptual painter, in a way.” Magritte painted The Treachery of Images in 1929, two years after his first solo exhibition in Brussels at Galerie Le Centaure and his move to Paris in order to be closer to the Surrealist set. It was a time of rapid production for the artist, whose first Surrealist painting, The Lost Jockey (Le jockey perdu), had only been produced three years earlier, in 1926. Rendered as if popping out from the page, the pipe’s image is robustly real, yet it is, as Magritte insists, certainly not an actual pipe. About the image, Magritte said, “The famous pipe. How people reproached me for it! And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it’s just a representation, is it not? So if I had written on my picture ‘This is a pipe,’ I’d have been lying!”

The painting has become a visual rubric for understanding resemblance and similitude. For example, in his 1993 critical-treatise-cum-comic book Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud draws 10 frames with his Dante’s Virgil-like protagonist (he goes by the name Scott McCloud) standing in front of Magritte’s painting. “Here’s a painting by Magritte called ‘The Treachery of Images,’” the first speech bubble reads. He continues, “The inscription is in French. Translated it means ‘This is not a pipe.’ And indeed this is not a pipe. This is a painting of a pipe. Right? Well, actually, that’s wrong. This is not a painting of a pipe, this is a drawing of a painting of a pipe. N’est-ce pas? Nope. Wrong again. It’s a printed copy of a drawing of a painting of a pipe. Ten copies, actually. Six if you fold the pages back. Do you hear what I’m saying? If you do, have your ears checked, because no one said a word.” Incidentally, and perhaps proving the seminal importance of Magritte’s coupling of words and imagery, Art Spiegelman, the celebrated comics artist (who is also featured in this issue), crafted an avant-garde children’s book, Open Me I’m a Dog, in 1997 that explored the conceptual nature of Magritte’s painting.

During this period Magritte not only challenges the perception of commonplace objects in everyday life, but also commonplace subjects in fine art. In The Eternally Obvious (1930), he paints the traditional female nude. However, he divides the body into five separately framed sections. Magritte referred to the work as an “object,” and along with two similar multi-part works or “toiles découpés” (“cut-up paintings”), he intended to present Eternally Obvious mounted on glass (these three works will be shown together in this exhibition for the first time since 1931). In The Rape, painted in 1934, when Magritte is again living in Brussels, the artist conflates a representation of a woman’s face with her body. André Breton, the French writer who defined the tenets of Surrealism, used this image for the cover of the 1934 book Qu’est-ce que le Surréalisme? (What is Surrealism?), which is also on view. In this painting, as Magritte expressed it, “The breasts are the eyes, the nose is a navel and the vagina replaces the mouth.” The image is startling, not only because familiar things are not where they belong, but because of the similarities Magritte’s depiction establishes.

In Attempting the Impossible (1928), a man and a nude woman stand turned toward one another; the man is a painter with palette and brush, and the woman is a life-size artistic rendering, or so it seems, almost complete save for an arm, which the painter is dabbing with paint. The image is an isolated moment in time. There is a potential energy present in the painting, and one anticipates that the arm will be painted to completion; however, as of 2013, it has not. On view are multiple photographs—additional isolated moments in time—that capture this painting. One entitled Love, by an anonymous photographer, recreates the painting’s scene; another, René Magritte and “Attempting the Impossible” (also by an anonymous photographer) pictures Magritte painting the painting—it doesn’t get much more meta than that.

Magritte was fond of depicting the artist, but also of depicting paintings of paintings. The Human Condition, a work from 1933, is his first painting to do this. An open window with curtains pushed on either side, shows a cloudy, blue sky and a patch of grass, while on an easel directly in front of the window sits an unframed canvas with a trompe l’oeil landscape that has the same cloudy sky and the same grass. The canvas and vista blend seamlessly, giving the illusion that with the canvas moved, the only thing missing would be the canvas’ outline. Besides the optical illusion, there is also a conceptual one—the view from the window seems as though it is the “real” image, while the canvas blocking it is the “representation.” However, both images are representations created by Magritte.

Another common trope throughout the works in the MoMA exhibition is repetition and doubling. It is seen not only in single works—Not to be Reproduced (1937) for instance (which, as it turns out, features a depiction of The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket by Magritte’s favorite writer, Edgar Allan Poe, a master of the doppelganger story, and also featured in this issue)—but also in multiple, similar works, such as Objet peint: oeil (1932/35) and Objet peint: oeil (1936 or 1937). “He’s known to have been interested in stereoscopic imagery, and though it’s perhaps not as well documented, he’s very fascinated with what you can do with a camera,” says Umland. “He’s interested in casting doubt on the nature of appearances. For him doubling and repeating, and the relationship between the original and the model, are key strategies he employs. It’s very interesting to see this influence in the work of later artists, like with Rauschenberg’s Factum I and II.”

Throughout the exhibition, MoMA’s wall texts rely heavily on letters between Magritte and the Belgian Surrealist author and confidant Paul Nougé. Nougé is even depicted in a number of images. The writer, who was prominent in Europe but whose legacy has suffered west of the Atlantic due of a lack of English translation, described in depth many of the elements of Magritte’s paintings. “A favorite quote of mine related to Magritte was written by Nougé around 1930,” says Umland. “‘To look at Magritte’s paintings and to turn away and look at the world again, is to realize that the world has been altered.’” After looking at MoMA’s exhibition, it is difficult to see modern imagery the same way again—whether it’s hanging in the museum’s collection or being scrolled through on the computer screen.

![René Magritte, La trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (The Treachery of Images [This is Not a Pipe]), 1929, oil on canvas.](https://www.artandantiquesmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/201312_magritte_01-150x150.jpg)