Robin White

Robin White in her studio in Masterton, New Zealand. Photo © Bruce Foster

I’ve conceived all of the works as conversations – between Matisse and myself, and between myself and other people whom I introduce him to.

New Zealand artist Robin White’s hometown of Masterton – or Whakaoriori, as it is known to Māori – is more than an hour’s drive from the nearest beach. This is the furthest she has ever lived from the Pacific Ocean – a body of water that runs like a tidal system through her art, tracing its past and determining its future direction. This oceanic reality is a territory she shares with Henri Matisse, a painter she has deeply admired since student days and whose life, art and influence are explored by White and fellow contemporary artists Nina Chanel Abney, Sally Smart and Angela Tiatia in Matisse Alive.

Born in the North Island town of Te Puke in 1946, White was taught by Colin McCahon at Auckland University’s Elam School of Fine Arts. By the 1970s she was established as a leading New Zealand painter; a creator of iconic, defining images of figures in landscape. Drawing subject matter from her immediate surroundings – Paremata Harbour (just north of Wellington) and Otago Peninsula – White played an integral part in the revitalisation of the country’s regionalist art. While her works still have deep roots in specific locations, any constraining notion of regionalism has been blown apart by the pan-Pacific nature of her work since leaving New Zealand in 1982 for what would be a 17-year residence on Tarawa, in the Republic of Kiribati.

White has tribal affiliations with Ngāti Awa, a Māori iwi centred in the eastern Bay of Plenty region. If her family background and upbringing introduced her to Māori as well as Western culture, her time on the equatorial atoll and frequent, ongoing travels around the Pacific – or Oceania, as she likes to call it – have enhanced her awareness of the broader region. Energetic and with a formidable work ethic, White considers herself resolutely ‘mid-career’ and her output over recent years reflects an impressive capacity for both studio work in Masterton and projects involving much travel and collaboration with individuals and communal groups in Tonga, Fiji and elsewhere.

Looking back on her time on Tarawa, White makes the point that she has never left the Pacific, Aotearoa/New Zealand being just another of the region’s island groups. (These days, Auckland is not only the air and sea transport-hub for the South Pacific, it is also the world’s largest Polynesian city.) The artist wears a hair comb with the placename Kiribati etched into it, signalling her attachment to the remote island nation.

Arriving in Tarawa, White soon realised that oil painting was not likely to be a viable option and that she would need to adapt to the particular demands of her new working environment. A devastating house fire in 1996, which destroyed her studio and all her art materials, further galvanised her decision to work as much as possible with local materials, natural dyes and traditional processes. All four of her works in Matisse Alive – a celebration of the French artist being held in conjunction with Matisse: Life & Spirit, Masterpieces from the Centre Pompidou, Paris – are made from paperbark (known as tapa in Tonga, masi in Fiji), natural dyes and pigments; two of the works were made in collaboration with her Tongan friend Ebonie Fifita and with the subsequent participation of others from Auckland’s Pasifika community.

Robin White artworks on display in Matisse Alive

White’s Hufanga’anga 2021 offers an abstract response to the South Pacific – a nocturnal (or deep sea) counterpart to Matisse’s bristling, light-infused Pacific, as manifest in his late cut-outs and works like Polynesia, the Sea 1946 which travels to Sydney from France for the exhibition. In White’s three other paperbark works in Matisse Alive, the genre of ‘domestic interior’ so beloved of Matisse is infused with a Pacific consciousness. In all these works, White pays homage to Matisse’s love of textiles (he came from Picardy, a textile-manufacturing region in Northern France).

Throughout his life he was drawn to ‘things that delight the eye and the heart’, as White puts it. Whether contemplating his own painting or the tapa he collected avidly throughout his life, Matisse ‘really understood pattern, the role of pattern, the ligaments of a work.’ That was a lesson White learnt from him: ‘The way pattern pulls you through a work.’ In turn, Matisse had absorbed much from his life-long interest in decorative arts and, later, from his experiences in Tahiti, where he learnt, by his own reckoning, ‘the meaning of the horizontal and the vertical from the shoreline and the coco palms’.

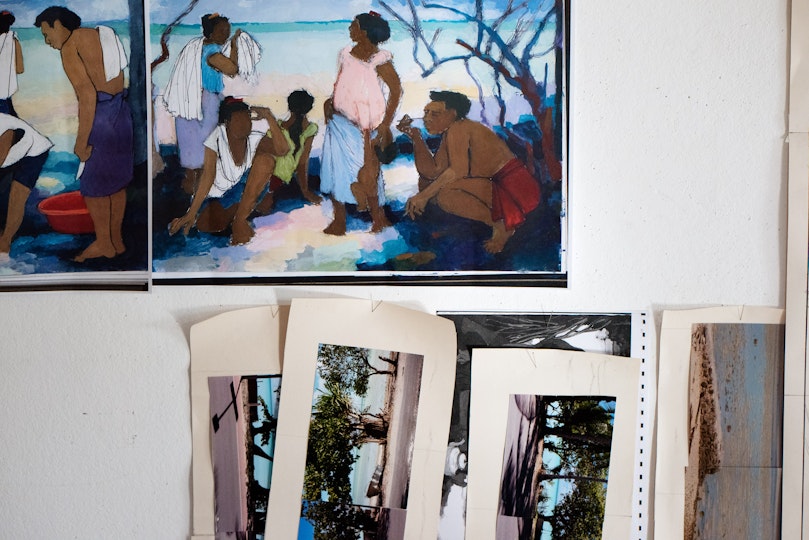

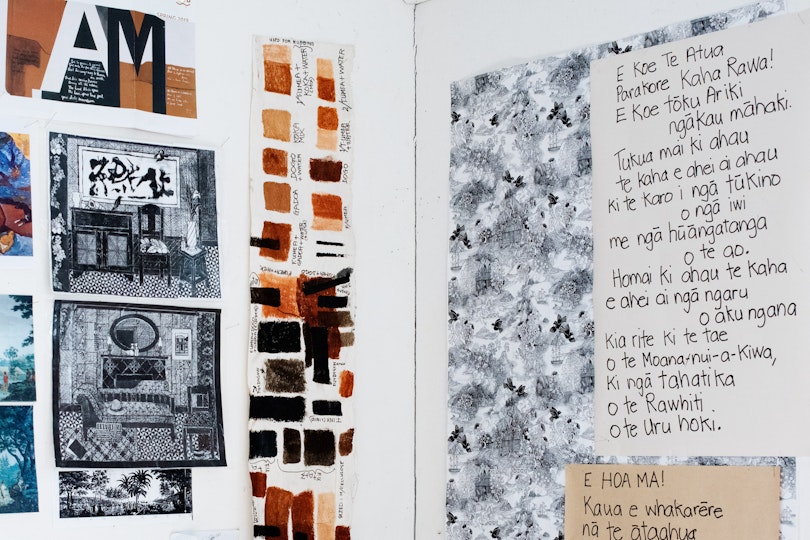

Just off to one side of the late-19th-century cottage White shares with her husband Michael Fudakowski, the artist works in a garage/studio, the walls of which have a journal-like layering of words and images, all of them in a constant state of revision and adjustment. Pinned to one wall is a handwritten lexicon of Māori words; elsewhere there are poems and phrases from other Pacific languages and samples of natural dyes and pigments. Large working drawings and sections of paperbark are also pinned to the walls, or rolled, or laid flat on her workbench. Outside this busy, light-infused space, a thriving vegetable garden, with its productive clutter of ground-level and aerial growth, has taken over the back section.

Robin White in her studio in Masterton, New Zealand. Photo © Bruce Foster

Inside Robin White’s studio in Masterton, New Zealand. Photo © Bruce Foster

Inside Robin White’s studio in Masterton, New Zealand. Photo © Bruce Foster

Inside Robin White’s studio in Masterton, New Zealand. Photo © Bruce Foster

Art, for White, has always been both a distillation and an accumulation. While visual source material proliferates in the studio, books clutter her living room. Over the past two years, she made a point of reading Hilary Spurling’s magisterial Matisse biography and Paule Laudon’s Matisse in Tahiti. It was, however, an earlier visitor to the Pacific who first led White towards a deeper awareness of the region: the novelist Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–94), who spent the last years of his life in Samoa. In 1888, Stevenson visited Hawai’i en route to Samoa, and spent four months in the Gilbert Islands [Kiribati]. ‘I read his autobiography about his experiences in the Pacific,’ White recalls. ‘The book left me feeling as if he was my big brother – the way he responded so warmly to the people he met. He was very decent. And so, for that matter, was Matisse.’

Acknowledging Matisse’s cultural baggage as an early-20th-century Frenchman arriving at the tail-end of colonialism, White sees him as existing outside that history: ‘I don’t have any hang-ups about Matisse. I don’t even think of Matisse as being male or female: he is a revered ancestor. I think I would have enjoyed his company.’

She read, in Spurling’s biography, how it was the light of the Southern Hemisphere that drew Matisse halfway around the world. ‘Pure light, pure air, pure colour,’ he said, ‘and that undersea light which is like a second sky’. An image lingers in White’s mind of the 60-year-old arthritic artist, shoulder-deep in a soothing tropical lagoon, wearing homemade wooden goggles: ‘He would watch the birds on the horizon gathering into a cloud, spotting the schools of fish in the clear water below. He would then pop his head under the water and watch them diving. That experience of seeing birds going from being airborne creatures to being like fish had a big effect on him. Sky and sea had become interchangeable, and from there it is a segue into the cut-outs … That had resonance for me, having lived on an atoll for so long.’

White recalls that ‘sense of losing sight of the boundaries and seeing things intermingling’ as being the quintessential Oceanic experience. Besides diving into Oceanic reality, there is another manoeuvre implicit in her recent works – a dive back into her own life story. Upon encountering Matisse’s paintings of interiors in North American museums in 2018, she noted in her journal his use of ‘a contained space … where the only way out is through the painting itself’. She recognised this as being exactly what she was trying to do in the sequence of paperbark works which led up to the works in Matisse Alive: ‘I’m thinking back to my childhood and I’m in my parents’ bedroom standing in front of the dressing table mirror and like Alice through the looking glass I am wishing myself to enter that space. I’m recalling the intensity of the feeling and the excitement and the fact the imagined space and the act of imagination itself is far more compelling than reality.’ With their flickering patterns and coded narratives, White’s new works breach the boundaries between natural world and imagined or remembered spaces.

Robin White with Ebonie Fifita Soon, the tide will turn February 2021, courtesy of the artists © the artists

‘I’ve conceived all of the works as conversations – between Matisse and myself, and between myself and other people whom I introduce him to. In Soon, the tide will turn, I’m imagining what might be the conversation in the next world between Matisse and Peter McLeavey [White’s late Wellington gallerist] and Robert Louis Stevenson. What would they say to each other about their relationship to the Pacific?’ White herself is very much a part of that conversation too, with an adaptation of her 1970 screenprint Mangaweka hanging on the wall behind. The wall hangings and mats in the work belong equally to Matisse’s art and to Polynesian tradition. The chaise longue, White says, is lifted from Peter McLeavey’s Wellington gallery; the hat is Matisse’s, the pattern on the back wall is from one of the rooms in Stevenson’s ‘Vailima’, his famous house in Samoa. ‘The journal on the floor is mine. Or it could be anybody’s.’ Contemporary realities are signalled by the hand-sanitiser-dispenser, which is given an almost religious significance, placed on the mantelpiece beside a conch shell and between two lamps reminiscent of those painted by Colin McCahon.

The title Soon, the tide will turn came from a letter Peter McLeavey wrote to White during the early 1990s, when she was worried about how the family was going to make ends meet living on Tarawa. Her gallerist noted that the New Zealand public had come to expect ‘icons of place’ from White, which made her ‘offshore’ works hard to place. The Pacific, at that time, felt to most New Zealanders like an alien territory, he rightly implied. Since then, that situation has changed dramatically, with White’s work not only reflecting but also helping to advance a reconfiguration of the Pacific/Oceanic reality, with Aotearoa/New Zealand as an integral and vital component. ‘The Pacific is intrinsically diverse,’ White says. ‘It contains a multitude of stories and situations.’ With their abstracted and figurative elements, her tapa-works are perfectly placed to reflect and enlarge upon Oceanic realities. ‘The ocean is very fluid,’ she says, ‘it flows from shore to shore – it doesn’t know boundaries … It is open and accepts what it is offered, for better or worse.’

The largest work of White’s in the exhibition, VAIOLA, measures two metres by five metres and includes in its wide catchment of materials and inspirations a poem by ‘Akesa Fifita (grandmother of two of White’s most frequent collaborators, Ruha and Ebonie Fifita). A pattern denoting ocean waves traverses the six windows, four of which feature hitched Matisse-inspired curtains. In the context of ‘Matisse alive’, the two chairs placed in front of a teeming tropical backdrop could represent Henri Matisse with his companion and caregiver during his time in Papeete, Pauline Schyle. Or it could be White herself sitting beside him – student and teacher, European and Polynesian, Westerner and Antipodean – in a shared space, both paying homage to an Oceanic reality that stretches far beyond both of them.

You can go behind-the-scenes of the making of VAIOLA in this video.

And hear from Robin White about her work for Matisse Alive as she joins broadcaster Daniel Browning in conversation.

A version of this article first appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine