KEARNEY — The 100th Bombardment Group is one of the most storied units of World War II and they spent several months at the Kearney Army Air Base before being shipped off to the air war of German occupied Europe.

A new Apple TV+ series, “Masters of the Air,” follows the actions of the 100th Bomb Group, a unit which flew B-17 Flying Fortress with the Eighth Air Force during World War II.

They earned the nickname the “Bloody Hundredth,” due the heavy losses they sustained through combat missions over Europe.

“Masters of the Air,” premiered on Apple TV+ on Jan. 26, 2024.

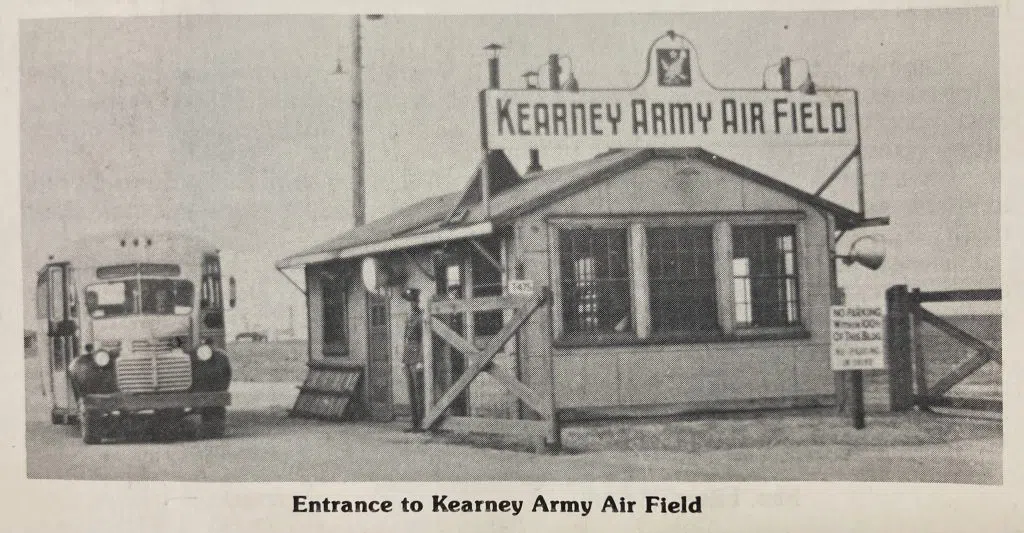

Kearney Army Air Base

The entrance to the Kearney Army Air Field, (Buffalo County Historical Society, Courtesy)

By late 1942, the Allied cause during World War II was in a better position than it had been earlier in the year.

Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa was soon to take place, the Marines were digging in on Guadalcanal and the Soviets were pulling back to the eventual graveyard of the German 6th Army, Stalingrad.

Back on the home front, the United States was working to gear up its immense industrial capacity and to build bases across the country that would eventually house the new equipment and service members.

Locally, Kearney, Grand Island and Hastings joined to form the Central Nebraska Defense Council when it was learned that the United States Army Air Forces was considering the site for a military airfield.

The group attempted to convince Washington that central Nebraska was suitable. Kearney and Grand Island effectively competed as locations for defense airports which would serve as storage for aircraft made at Offutt Field and the Glenn L. Martin Bomber Plant near Omaha.

As early as 1941 the City of Kearney voted on a $60,000 bond to finance a new airport, which was officially dedicated as the Keens Municipal Airport on Aug. 24, 1942.

Not long after, Kearney learned the Army was considering the site for a military airfield. “Construction was approved on Sept. 5, 1942, for the Kearney base and for satellite fields at McCook, Grand Island and Harvard,” according to a 1988 Buffalo Tales publication, produced by the Buffalo County Historical Society.

“The City of Kearney not only offered the use of the Keens 532-acre airfield but signed a long-term lease with the Army for only $1.00 per year for as long as the field was needed. An additional 2,227.5 acres of farmland was condemned by the Army to provide more room,” the publication stated.

Construction contracts were awarded throughout the fall and much of the newly laid asphalt for Keens field was plowed up to make way for thicker and wider concrete runways which would support the Army Air Forces aircraft.

“Paving operations were initiated on October 6 and were completed by November 24, a period of seven weeks. One thousand cars of cement were used, enough cement, it was said, to pave a two-lane highway from Kearney to McCook,” the Buffalo Tales publication stated.

With the concrete paving complete, the work then turned to putting up the buildings and laying utility lines.

“The project gathered speed as warehouses, hangers, barracks, post office, recreation hall and post exchange, hospital, theater and chapel were built,” Buffalo Tales stated, “By the end of November construction had progressed to the point that a commanding officer was needed to receive the equipment accumulating at the base.”

A handful of buildings from the military era remain at Kearney Airport, notably Hangar #385.

The majority of the work on the Kearney Army Air Base was completed by January 1943, and training units began to arrive in Kearney during the same month.

The first military aircraft arrived on Feb. 4 when a squadron of B-17 Flying Fortresses arrived. The base served a dual purpose during 1943, one for training and one for processing.

One of the first units to train at the Kearney base was the 100th Bombardment Group.

Bloody Hundredth

The 100th Bombardment Group had been activated by the Army Air Forces in June 1942.

The first cadre of the unit had been moved to Walla Walla Army Air Base in Washington. It received its first four air crews and four B-17s from the Boeing factory in Seattle.

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was a four-engine heavy bomber that had been developed in the 1930s. The aircraft would be used primarily in the European Theater, and it dropped more bombs than any other aircraft of the war.

Of the roughly 1.5 million tons of bombs dropped on Nazi Germany and its occupied territories by Allied aircraft, over 640 000 tons, 42.6 percent, were dropped from B-17s.

It was the third most produced bomber of all time and from its inception, the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) promoted the aircraft as a strategic weapon.

It was a relatively fast, high-flying, long-range bomber with heavy defensive armament at the expense of bombload. It also developed a reputation for toughness based upon stories and photos of badly damaged B-17s safely returning to base.

The B-17 was primarily employed by the USAAF in the daylight component of the Allied strategic bombing campaign over Europe, complementing RAF Bomber Command’s night bombers in attacking German industrial, military and civilian targets.

A B-17 Flying Fortress over Europe, (National Archives, Courtesy, Photo: 204899072)

The aircraft carried a crew of 10, a pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier/nose gunner, flight engineer/top turret gunner, radio operator, two waist gunners, a ball turret gunner and a tail gunner.

The German adversary initially did not think much of the United States industry.

Luftwaffe boss Hermann Göring reassured Adolf Hitler, that the B-17 was of miserable fighting quality, and the Americans could only build proper refrigerators.

On New Year’s Day, 1943, the members of the fledgling 100th BG transferred operations to two separate bases.

The aircraft and crews moved to the Sioux City Army Air Base in Iowa, while the ground crews traveled to Kearney Army Air Base.

“Kearney’s functions as a processing center started in February 1943 when the Army Air Corps assigned a heavy bombardment processing unit to the based to prepare B-17 crews for overseas duty,” the Buffalo Tales publication states.

“The 100th became the parent group responsible for producing cadres for new Army Air groups being formed and for training of new combat crews. The ground crews were stationed at Kearney while the air crews were divided among various bases where they served as instructions,” Buffalo Tales stated.

Jack Schmitz, Jr., was one of the early arrivals and he describes his time at the Kearney Army Air Base.

“I arrived at the base in the early part of 1943. Really wasn’t much there at that time. We were in the process of getting the B-17 bomber ready and outfitted for combat duty…We checked them out as to all equipment, oxygen, armament, engine checks, etc., for overseas duty and flown to Presque Isle, Maine, where they were installed with ammunition and bombs and flown to England,” Buffalo Tales recorded.

By mid-April, the 100th BG aircrews joined the ground echelon at Kearney and new B-17s were delivered. Both groups underwent additional training.

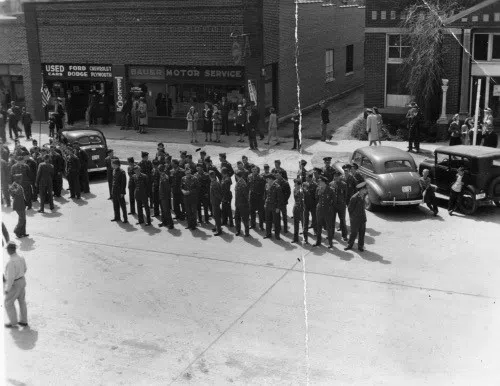

On April 16, 1943, the serviceman of the Kearney Army Air Base, including the 100th BG put on a bond drive parade through downtown Kearney.

“Kearney Army Air Base won plaudits of the people from Buffalo County Thursday when it took the lead in participating in an ‘all out for bonds’ parade staged on the streets of Kearney. Nearly ten thousand persons saw the military personnel from the base on their first ‘dress appearance’…While the parade was moving through the streets, formations of mighty Flying Fortresses swooped down over the city to add to the thrill of the military display,” stated the Kearney Air Base News on April 23, 1943.

Members of the 100th BG in downtown Kearney during the spring of 1943. (Bill Carleton Collection, Courtesy)

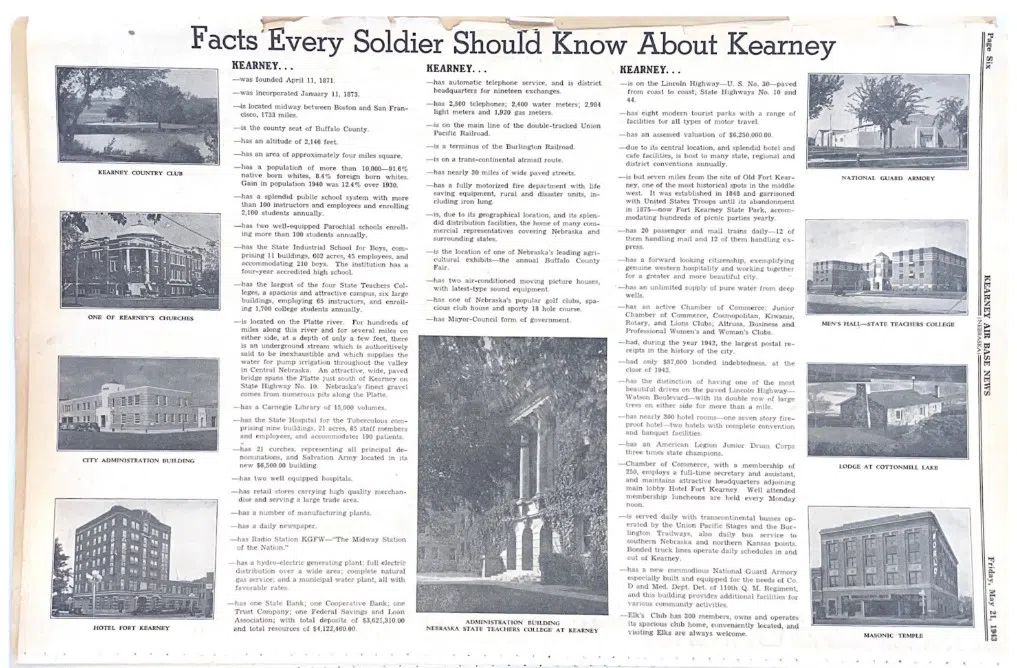

The community of Kearney did their best to take care of the flood of young servicemen.

“A husting group of business and professional men and women in Kearney compose one of the most important organizations where the solider is concerned – The War Recreation Board,” The Kearney Air Base News stated.

“This group of Kearney people has set up the USO program and has been instrumental in solving a hundred little problems that have come up in regard to soldiers and the town of Kearney,” the Base News stated.

A page in the Kearney Air Base News newspaper that highlighted places to visit in Kearney, (Buffalo County Historical Society, Courtesy)

Even closer to home, local Kearney radio station KGFW did its part to keep the servicemen entertained.

“Anson Thomas, manger of radio station KGFW, which carries two base programs already, has announced that there will be a direct wire from the base available in the near future,” the Kearney Air Base News stated.

“This will make possible the staging of shows direct from the field and will allow military personnel to see the programs as they are sent out on the air. Sergeant Hugh Benson will emcee the shows broadcast from the base. Talen for the programs is now being sought by Sergeant Benson,” the report concluded.

In another article titled, “Officer’s Club Dance Success Despite Rain,” it stated that fifty women from the Kearney State Teacher College were gusts of the officers and danced to the music of Ellie Frazier’s band.

On April 7, 1943, Mayor of Kearney, Ivan Mattson issued a statement to the officers and men at the Kearney Air Base.

“It is pleasant to extend a genuine welcome to a group of real Americans such as you. The City of Kearney wanted to do something in this war effort. You have brought us the opportunity. We extend our hand, we give you our recreational facilities, our parks, our churches, our homes and our sincerest friendship. May the days you spend among us be forever remembered by us all.”

It wasn’t just Kearney residents that did their best to welcome the servicemen.

“Residents of Minden, Nebraska are preparing a gala for approximately 150 soldiers stationed at this base, according to Charles R. Smith, editor of the Minden Courier,” the Kearney Air Base News stated.

“Mindenites have issued an invitation for that many soldiers to be their guests at a party, social and public program in the near future.”

After a community barbecue that was attended by men on the base, one sergeant was teased in the newspaper by one of the writers in the unit.

“Miracle of miracles, Sgt. Jimmy Bullard staying sober with all that free beer floating around. He must have been on the wagon.”

As part of a long-range training exercise, the original 35 crews of the 100th BG were to fly from Kearney some 1,300 miles to Hamilton Field near Novato, Calif.

Having taken advantage of disjoined and poorly coordinated training schedules, the air crews took advantage of the lack of oversight.

An inspection on the ramp in Kearney during the spring of 1943, (Bill Carleton Collection, Courtesy)

As a result, the entire exercise was a debacle, with units scattered all over the western United States. While some bombers made it to California, three ended up in Las Vegas. One bomber event went in the opposite direction and ended up at Smyrna, Tenn.

“Given that the pilot’s wife just happened to be in Smyrna, the crew’s wrong-way journey was probably not a gross navigation error,” the National World War II Museum stated.

Prepared or not, the crews flew to England on May 25, 1953, and arrived at Station 139, Thorpe Abbots, England on June 8, 1943.

Baptism By Fire

It wasn’t for nothing that the 100th BG would earn the nickname, “Bloody Hundredth.”

The group flew its first mission on June 22, but this was just a diversion flight over the North Sea to confuse the German interceptors.

However, three days later, the 100th BG would conduct its first combat missions against the U-boat yards at Bremen, Germany.

The rapid pace of aviation technology created the belief that groups of heavy bombers would be able to devastate cities at will. This theorizing led some to believe that these bombers would be capable of fighting their way to a target, drop their bombs and fight their way out.

The idea was best encapsulated by British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin who warned in 1932, “The bomber will always get through.”

Baldwin’s statement was essentially correct, but it is likely he did not anticipate the cost in aircrew and aircraft the air campaign would require.

With their heavy bombers at the ready, the USAAF adopted the strategy of taking on the Luftwaffe, the German air force, head on, in larger and larger air raids by mutually defending bombers, flying over Germany, Austria, and France at high altitudes during the daytime.

The two USAAF Air Forces that bore the burden of the fighting in the European theatre were the Eighth Air Force, of which the 100th BG was part of, and the Fifteenth Air Force.

The American command did not see the need for long-range fighters in 1942, but this would rapidly shift as 1943 progressed and the losses began to increase to an untenable rate.

The efficiency and performance of the German fighter arm reached its peak during 1943. Without an escort fighter with sufficient range, USAAF bombing raids into Germany proper were costly.

The German fighters were becoming more heavily armed to deal with the American bombers. Many carried multiple cannons, others would carry motor tubes to lob explosives at the bombers. Later in the war, rockets would be used to break up bomber formations.

B-17s fly in formation among clouds of flak shot by German defenders, (National Achieves, Courtesy, Photo: 204898381)

In turn, USAAF adoption of the combat box formations placed a score or more of bombers together for mutual defense, with dozens of heavy .50 caliber Browning M2 machine guns, up to 13 per aircraft, aimed outwards from the formations in almost every conceivable direction.

The raids had an enormous effect on the German distribution of weaponry.

In 1940, 791 heavy anti-aircraft gun batteries and 686 light batteries protected German industrial targets. By 1944, the size of the anti-aircraft arm had increased to 2,655 heavy batteries and 1,612 light batteries.

All these defenses, plus an unescorted bomber force, meant that the average life of a B-17 crewman in 1943 was only 11 missions. They had to fly 25 missions before their tour was complete.

“Flying in a formation comprised of 275 bombers, the 100th sent 17 B-17 crews, who sighted their first German fighters while also receiving their initial barrage of ground-based Luftwaffe flak,” the National World War II Museum stated.

The force lost 18 bombers, with the 100th BG losing three and 30 airmen killed or captured.

Norman Goodwin was a ball turret gunner on one of the aircraft that was shot down.

“On the second pass we really got it. A 20-millimeter shell hit just to my left, exploded, and almost tore my leg off. The side of the plane looked as if someone had thrown a ripe tomato at it,” Goodwin recalled, “The jump signal itself never came, because the pilot had been knocked out. The plane went into a spin…without warning the plane broke apart, then the plane blew up.”

More Missions, More Losses

Although the 100th BG did not have had the highest over-all loss rate of any group in the Eighth Air Force, it did have heavy losses during eight missions to Germany.

100th BG Sgt. Leon Castro, 22-years-old, told the Arizona Daily Star newspaper, “We met opposition as soon as our fighter cover left us a short time inland from the channel. From there on it got tough. They had everything in the air. Of course, there was a lot of flak, there always was…We kept on toward our target and fought it out.”

On Aug. 17, 1943, the 100th BG would take part in a mission that would help cement its infamous reputation.

Part of the 4th Bomb Wing, the group took part in the first shuttle mission, flying from East Anglia, bombing the German aircraft factories at Regensberg, Germany and then flying on to North Africa.

The 100th BG would be flying in the lowest and trailing squadron of the larger bomber combat box; this position was known as “Purple Heart corner.” The German fighters would often attack this location first and then work their way through the formation.

The overall force lost 24 bombers, while the 100th BG alone lost nine of its 22 aircraft, a 40 percent loss rate. The 100th suffered more than any other group on this mission.

The worst was yet to come.

Perhaps no other raid helped to earn the 100th BG their nickname as the Bloody Hundredth as much as the Munster, Germany mission of Oct. 10, 1943.

The target was worker’s housing in the Ruhr Valley, German’s industrial heartland and thus a heavily defended area.

“The men were worn out, their ranks severely depleted due to the losses sustained in the previous two raids. Nevertheless, they rose again early on the morning of the 10th for a preflight briefing,” the National World War II Museum stated in an article.

Vapor trails from B-17’s flying in formation, (National Achieves, Courtesy, Photo: 204840337)

The 100th BG launched 13 planes that joined a force of 307 B-17s headed for the target. The Germans would respond by throwing 350 fighters at the bomber stream.

“Wave after wave of German aircraft made head-on passes at the low group in the formation, the 100th Bomb Group. As one wave of fighters broke away, another slashed through the B-17 formation, and then another and another. The Germans passed so close that the Americans could see the scarves around the enemy pilots’ necks,” the National World War II Museum noted.

As they neared the city center, the German fighters were replaced by accurate anti-aircraft fire that found the range and altitude of the B-17s.

“Bombers were hit heavily by the accurate enemy fire. While not nearly as devastating in intensity as Bremen, Munster’s flak was seemingly more accurate initially,” stated the National World War II Museum.

The shattered remnants of the 100th BG brought up the rear of the combat formation over Munster. Only six of the 13 B-17s were left flying in the formation.

German fighters attacked the formation on the way home before they were driven off by Allied fighters.

The 13th Combat Wing had been devastated, losing 25 of the 30 bombers that day. The Bloody Hundredth suffered the worst losses of the day.

“Of the 13 aircraft dispatched from Thorpe Abbotts that morning, only one reappeared in the sky over the air station that afternoon,” the National World War II Museum stated.

When the surviving pilot recounted how the 100th BG had suffered during the raid to a Lieutenant and his staff, he recalled, “The room was absolutely silent for a full half-minute…I could have heard a pin drop.”

The 100th BG’s mauling over Munster occurred the same week as the second Schweinfurt Bombing Raid, which would come to be known as “Black Thursday.”

“The reality was that deep penetrations into Germany without fighter escort were too costly. For the rest of 1943, the 8th Air Force limited its attacks to France, the European coastline, and the Ruhr Valley where fighter escort was possible,” the National World War II Museum stated.

(National Archives, Courtesy, Photo: 204841372)

Air raid planners avoid missions deep into Germany until the P-51 Mustang with its long range could escort the bombers all the way to their targets.

“Winning the air war would require new doctrines, equipment, and take much of 1944,” the National World War II Museum stated.

Legacy

Throughout their 1943 missions, the 100th BG had developed their reputation as the “Bloody Hundredth,” but the reality was they did not suffer statistically more than any other unit.

However, the raids over Regensburg and Munster had created a perception that was hard to shake for the airmen. Of the 35 original crews that departed Kearney in late May 1943, 27 were shot down, killed or captured, within six months of leaving Kearney.

Only parts of eight crews finished 25 missions.

The 100th BG would fly a total of 306 missions during the war, would drop 19,257 tons of bombs, 229 planes were lost or scrapped, 757 men were killed and 923 were made prisoners of war.

In the end, the 100th BG represents the story of all airmen who took the fight to Nazi Germany, 30,000 feet in the air, and overcame overwhelming odds to help bring the war to a conclusion.

Editor’s Note: The author extends his thanks to Buffalo County Historical Society for providing research materials and David Ott, a 2003 graduate of the University of Nebraska at Kearney’s Aviation Program and a commercial pilot based in Omaha, who assisted with research and procuring photos. Much of research came from Todd Peterson’s thesis on the Kearney Airbase.