Grass of Grace: Turkana women's noble role in Climate Change resilience

Women drawn from Pelekech group harvest grass on their 15.5 acre land in Turkana North, Turkana County.

The vast region is yet to stop the crisis-to-crisis loop, coming in the wake of the biting drought; the longest in 40 years. Flash floods have also left a trail of death and destruction, sweeping humans, crops and livestock, experts warning that the situation is worsening.

Data from the United Nations outlook report for June to November 2023 shows that 5.4 million Kenyans (32 percent of the country’s arid population) are food insecure.

Children are continually dropping out of school to help with home chores, as their mothers face unprecedented gender-based violence levels.

Women taking the lead

Among the indigenous Turkana community, women do the most. They cook, feed children, build houses, and walk for hours in the scorching heat in search of water for domestic use.

They have been caught up in conflict over scarce fodder and water on the Kenya-Sudan border and drought. Nevertheless, some women drawn from Turkana North and Turkana West sub-counties’ Lokore and Naremeto locations respectively, are taking the lead in livelihood restoration which they say is their new source of hope and path to dignity.

To achieve this, they are forming groups in a bid to wean off their families of decades of donor food reliance through climate resilience projects. Visibly tired of hunger pangs, and with little funds from development partners, two women-led groups are trailblazing the restoration of their once lush rangelands.

On a sweltering Saturday in Lokore, 57-year-old Ngorokolemu Amanikor leads a dozen women with pangas into the 15.5-acre Pelekech Environmental Rangeland Management Group grass-seeding farm at the foot of Lokore hills. They are here to harvest their several months-old thick grass.

“We want to be self-reliant, not to depend on any food donations as it takes away our dignity; we just want to grow this grass so that we make money and buy whatever we need,” Amanikor the treasurer of the group says.

Next to her is 30-year-old AyahayaLochorlo, a mother of nine, who says women are already reaping from the project. She has been able to raise fees for her children and access a loan from the group.

In earnest, she faults the youth for giving the project a wide berth. The project, she says, has cut short long-distance treks in search of water. Before the project, some lost their premature pregnancies while scrambling for water in dry riverbeds.

“For now, we can buy books for our children and clean water. With water at home, conflict has also reduced, as we no longer fight,” Mrs Ayahaya says adding that women who are yet to join the group, still go through hell to find water.

Water - the vital resource

Young boys are dropping out of school in droves in quest for work at the Lokore goldmines, located some 120 kilometers northwest of Lodwar town.

On the riverbeds of rivers Kalobeyei, Nasira and Tarach, young boys are scooping sand in search of drinking water as women queue for the precious commodity. Goats too gather here in shifts to take a sip.

Water scarcity has put a wedge between them and refugees in the neighboring Kakuma Refugee Complex and Kalobeyei resettlement. With uninterrupted tap water supply, the local community feels that refugees are treated better, as locals are left to starve.

“Every day after school, we use jugs to scoop sand in search of water and when we don’t find much, we end up going to ask for tap water from the refugee camps, where we are not liked,” Ewoi, 13, says, pointing to simmering tensions with their guests-turned-neighbors.

He adds that his friends miss school in search of water wells, as their mothers scavenge the vast, dry landscape for wild fruits or await the solemnly guaranteed donor relief food supplies.

50-year-old David Lojem, Lokore group’s custodian of grass seed bank, claims that women are put at the center of operations to hoodwink donors. The group has a handful of men whose work is to bundle harvested hay. Everything else is left for women, including planting, weeding, and harvesting.

“Donors prefer women in our midst, so we have no choice. We were taken through a two-week training in Baringo, and later in Naremeto Group, who are now our peers, to see how to plant, harvest seeds and bundle hay using local solutions,” Lojem says, adding that their group sells a kilogram of grass seeds at Sh1,000 while a bundle of hay is sold at Sh300.

Drought-resistant goats

At another 29-acre project site over 60 kilometers west of Kakuma town, members of Naremeto Environmental Rangeland Management Group, just like their Lokore counterparts, believe water scarcity is stifling them. They have dysfunctional feeder roads, and their unfenced grass field is exposed to theft.

“Our project would be successful if we had boreholes. We plant grass once a year because we don’t have water and have not harvested this year because of lack of storage space,” Joyce Emoru, Naremeto grass seeding project group vice chair says.

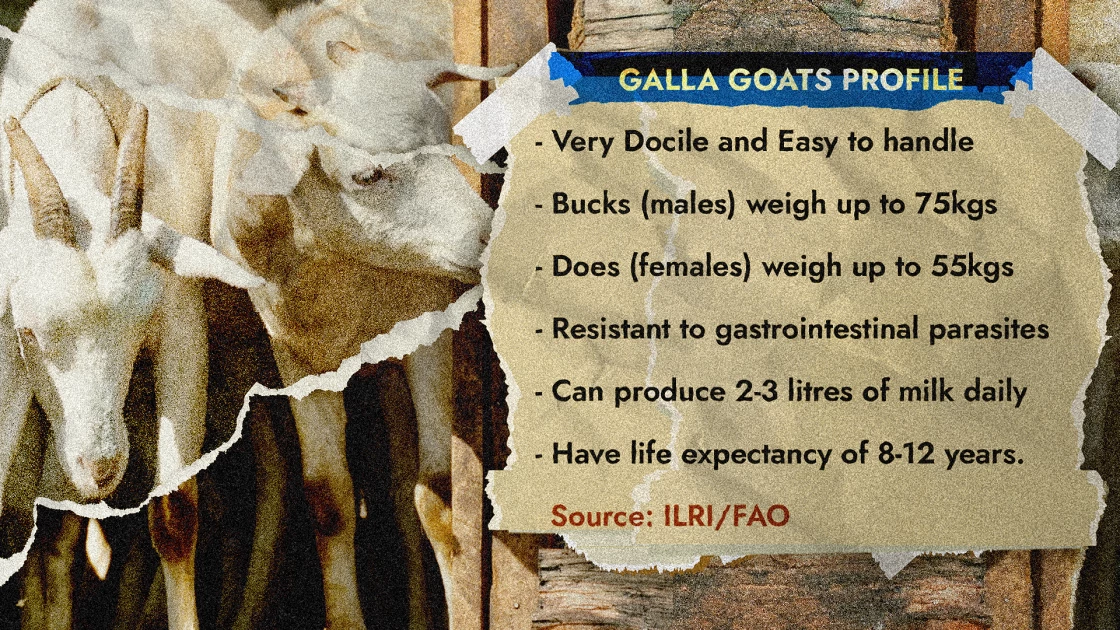

Nevertheless, the project is paying off. Emoru says that before the project, they had challenges raising school fees for their children. They equally trekked for kilometers in search of water and pasture. Currently, they have 30 well-fed, drought-resistant galla goats which they have been raising for the last two years.

“At the moment we are better off as we can afford a meal, even if it is once per day. The goats drink water twice a day. We milk them and when sold, these goats fetch as much as Sh30, 000. But we still need a steady supply of water,” she says.

According to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), galla goats are a breed native to East Africa and are well adapted to the harsh arid conditions making them a critical asset in resilience efforts. They also have high twinning rates, making them populate rapidly.

Experts in climate change and gender affairs observe that women and young boys’ participation in climate action is long overdue. Dr. Susan Chomba, the director of vital landscapes at World Resources Institute (WRI), explains that women and young boys in arid areas have over the years been the most affected.

“The burden on them is disproportionate and that is why they now think having water will help alleviate suffering and they will find more time for other viable activities,” Chomba says.

Her views are echoed by Anne Tek, the national coordinator of the Pan-African Climate Justice Alliance (PACJA), who observes that women are the missing cog in driving climate change resilience projects.

“Women are change makers and need to be fully funded to drive climate resilience programs,” Tek says, adding that the upcoming Nairobi climate summit this September would be a chance to get women to understand financing avenues for climate change action.

Sinking boreholes

On his part, Andrew Boki, a resident of Lokore who has broadcasted grass seeds on his dry farm awaiting rain believes that having boreholes will improve their livelihoods as they will ultimately switch to food production. Boki remains upbeat that water availability will keep them busy on their farms producing vegetables for sale to humanitarian organization staffers in Kakuma town.

“We want a steady supply of water so that we can grow food so that we don’t depend on aid. Selling grass alone is not sustainable and has its off-peak seasons. We need water to keep going,” he says.

However, Dr. Oscar Koech, University of Nairobi’s researcher and brainchild behind the two projects, faults the government for failing to harness rainwater, warning that sinking boreholes could exacerbate the impacts of climate change.

“Sinking boreholes is not the solution; we need to ask ourselves as a country what we do with rainwater that kills people, on the extreme. Reliance on borehole water means depleting the underground water, and with no replenishing mechanism we risk extremely harsh conditions in the future,” Koech says.

Weak policies

He adds that the underlying challenge has been reluctance by the government and private sector to invest in resilience projects. His views were echoed by Chomba who opines that Kenya, like the rest of the Horn of Africa region, has weak policies on rainwater harvesting.

“There is need to strengthen these policies but before then, sensitization of small holder farmers is key. Had we as a country invested in sensitizing farmers on the need to harvest water, we would be food secure,” she says.

The Horn of Africa region, for five consecutive seasons, has witnessed failed rains. This has compounded the situation leading to extreme cases of drought, famine, and floods.

Data from the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) shows that Turkana County lost over 56,000 animals in the last quarter of 2022. Lack of water was cited as a significant cause.

“We have been told El-Nino is coming and clearly, there are no elaborate plans to harvest the runaway rainwater. If stored, such water can be used to reduce the burden in those arid areas, and ultimately put to an end the ongoing conflicts,” Koech adds.

Field researchers, he adds, have had a rough time rolling out such projects at grassroots levels due to overriding political interests. These interests morph into insecurity incidences, forcing a halt to the projects altogether.

“Projects have stalled sometimes due to the overbearing nature of some elected leaders who disregard research and need-basis analyses. We have however piloted Samburu, Garissa, and Mandera counties, but need close monitoring,” he notes.

He observes that such projects have been successful in neighboring Somalia, as the private sector has invested in fodder production in addition to rearing improved galla goats. He adds that galla goat species have been identified as best suited for drylands.

“Israel is exporting powdered milk to Kenya. Our neighboring Somalia has high project success rates. The same has been seen in Ethiopia. So, why not in Kenya?”

“Case in point is a working example in Somalia where the private sector has taken a role in championing resource mobilization. We have seen investors put their resources into the projects,” Dr Koech adds.

Kenya, he reckons, has toyed with the idea, leading to an over-reliance on aid by pastoral communities. In July alone, Turkana County residents were supplied with 1,323.7 tons of cereals and another 109.3 tons of edible oils, data from the Lisha Jamii Programme shows.

As thousands of delegates gather in Nairobi this September for the African Climate Summit (whose theme speaks to small-scale resilience solutions with global impact), the hope of women in Turkana and other arid areas is to see a more pragmatic solution-based approach towards such programs.

Mohamed Adow, the director of an energy and climate think-tank, Power Shift Africa, draws the attention of the summit attendants to the urgency in swiftly addressing the growing appetite to invest in local communities through resilience projects, to alleviate the already inflicted suffering.

“The Africa Climate Summit offers the best opportunity to discuss ways to boost investments that will help communities on the climate frontline to adjust effectively. This meeting should emphasize ways of ensuring communities can live in dignity and thrive,” Adow says.

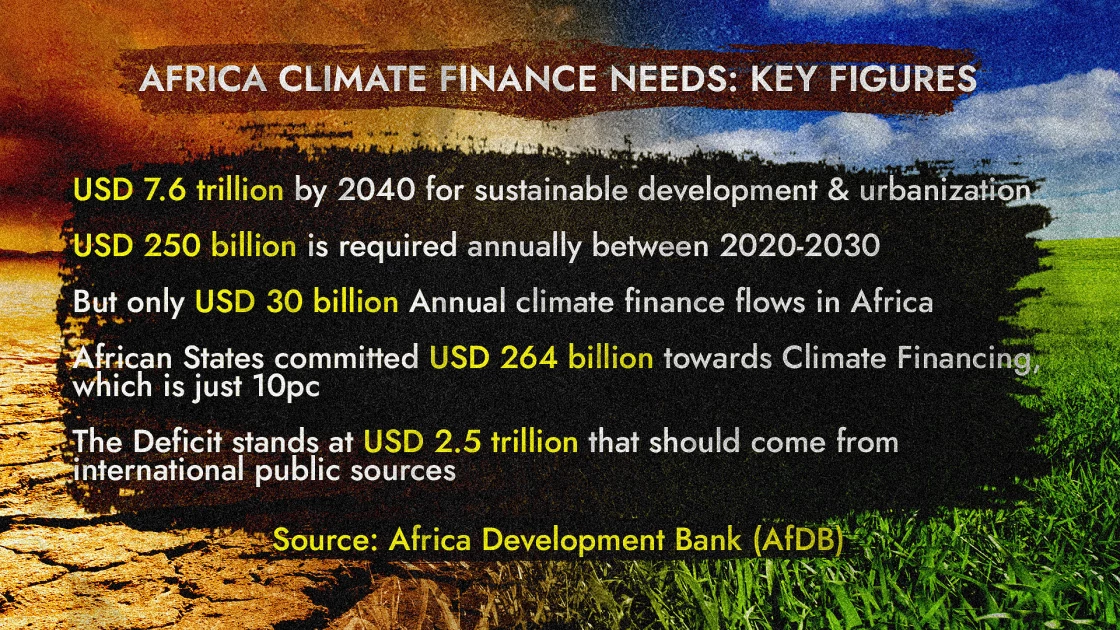

In as much as a recent report titled Africa’s Just Transition by Power Shift Africa puts Africa’s renewable energy potential at 50 times greater than the anticipated global electricity demand for the year 2040, financing gaps still stifle efforts to realize this.

This is the status quo even as the continent is continually supplying multibillion-dollar manufacturing firms in Europe and Asia with over 40 per cent of its reserves of key minerals for batteries and hydrogen technologies.

“We have an abundance of clean, renewable energy and it's vital that we use this to power our future prosperity. But to unlock it, Africa needs funding from countries that have got rich off our suffering. They owe a climate debt. But climate change in Africa is more than just solar panels,” Adow says.

Want to send us a story? SMS to 25170 or WhatsApp 0743570000 or Submit on Citizen Digital or email wananchi@royalmedia.co.ke

Comments

No comments yet.

Leave a Comment