For months at a time Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec lived as a proverbial fly on the wall of Paris’ brothels, recording their comings and goings in a series of prints titled Elles: ‘Women’. The suite was universally reviled – not for its sordid revelations, but because Lautrec had dared to depict their world without lust, shame or reproach...

Between the years 1892 and 1895 Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec insinuated himself in the brothels of Paris and Paul Gauguin among the women of Tahiti. Neither belonged in their new homes, but Lautrec could at least claim to be an outsider joining the ranks of his fellow rejects. Stunted by a rare medical condition, the conventional narrative is that he was drawn to the women of the bordellos because they had been condemned by their trade, as he was by disfigurement, to enjoy only carnal pleasures and never truly to love. But of their own lives in his he recognised and detested the moralising, pity and objectification that attended his disability. And so, in a series of ten lithographs published under the title Elles – ‘them’, the women of the night – he depicted their lives at their most tender and unglamorous: at their toilette, reclining in exhaustion and waiting in anticipation; the unerotic monotony of the in-between hours.

Femme Couchée, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

At the time he had been living and working for several years in Montmartre, without fixed abode. He would move between apartment studios, cafés and cabaret clubs, and his mother’s apartment on the Rue de Douai: a provincial haven in the midst of Parisian bohème, where Lautrec could entertain his guests. Then, for weeks at a time, he would decamp with great ceremony, paintbox in tow, to the local brothels on the Rue des Moulins, de Richelieue, d’Amboise or Joubert, where the parlours had remained more or less unchanged in operation since the 17th century. They were almost a public service, as sternly regulated as the navy. As Polynesia did for Gauguin, they offered for many men the liberation and exoticism of visiting another country, with rooms themed on oriental Persian harems. Contemporary newspapers advertised the nearby Moulin Rouge as ‘a very Parisian spectacle which husbands may confidently attend accompanied by their wives.’ Here, in the neighbouring brothels, the evening’s festivities could continue ‘confidently’ and covertly through the night, with wives and mistresses left at the door.

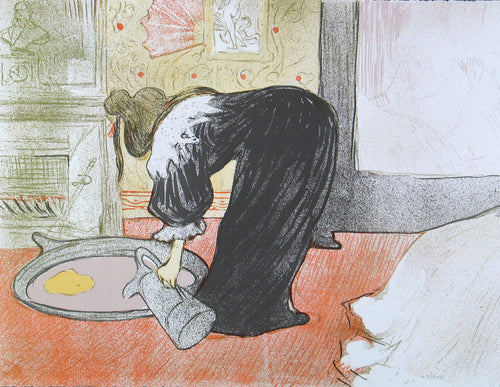

Le Tub, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Elles takes us to the heart of the trade, to rooms dressed in Rococo furnishings aspiring to the aristocratic splendour that Lautrec had grown up with and now enjoyed in his mother’s rooms. Here, he found himself caught in a curious position between the wealthy reality of his birthright and its fake equivalent in the brothel, just as the brothel workers who arrived as outcast young girls from the countryside, forced into the profession by destitution and neglect, now lived among the phoney windmills of Montmartre’s suburbs.

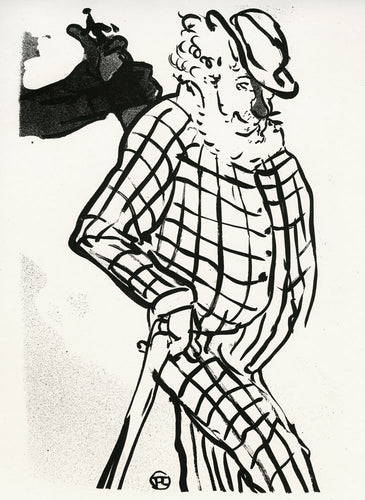

Le Gommeux (The Masher), Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Illusion and reality were central to Lautrec’s philosophy and he enjoyed the ambiguity of his role as a recorder of lives public and private. ‘I have endeavoured to depict the truth, and not an ideal,’ he wrote. ‘But this is perhaps a failing on my part, since warts find no favour with me and I am wont to embellish them with coy little hairs, to round them off and to give them an alluring sheen.’ The brothel made for an attractive subject, for its own truth was a masquerade, the great secret of Paris known to all. ‘What is art? Prostitution’ Baudelaire declared, and the whole of Paris a whorehouse: at once a symbol of modernity and an ancient institution (the oldest profession in the world, as the joke goes). In the venal, debauched and deprived streets of the city which he, Zola, Goncourt, and Huysmans all described, there exists no Platonic ideal. Here beauty is flesh, love the scent of a woman, truth currency, and the prostitute a tragic thief and heroine – like the artist selling his soul, courting bourgeois gratitude while enduring their derision and succumbing to the ravenous excesses of the age.

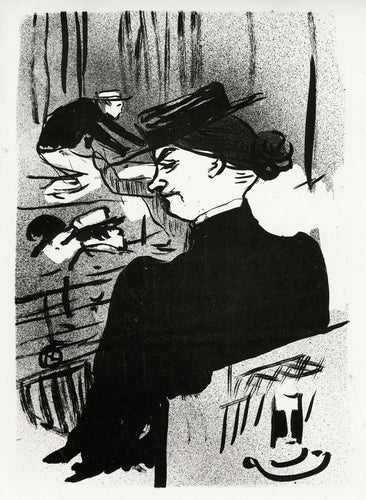

Devant la Glace, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Elles is not quite a ‘warts and all’ exposé of the hidden reality of the brothel: the layers of mock-lavish décor and dissimulation dressing up its essential purpose, which was the availability of naked, vulnerable women for pleasure. In place of coy hairs surface beloved of his lithographs, effected by flicking or spraying ink on the stone block, lends these images a mist like cigarette ash or champagne bubbles, as if they might be wiped clean. It’s just one of several clues in Lautrec’s own disclosing ‘code’ that suggests an unspoken truth underpinned by his scenes. A code of objects: top hats resting on chairs, vacated slippers, looking glasses, beds to be made and sheets already slept in, saucy pictures on the walls. Of fingers picking at hair, at combs, at mirrors, at corsets. And of colours too: a hot sex red, that of the red hair he obsessed over, and a mustard yellow shared with covers of avant-garde Parisian paperbacks that came to define the late 19th century as an era of scandal – like the copy of Zola’s Joie de Vivre, thumbed, dog-eared and soiled, that Van Gogh painted beside his Protestant father’s weighty bible.

Le Déjeuner du Matin, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Looking, watching, glances met and missed: voyeurism is the beating heart of Lautrec’s art. In the age of the camera, his pictures were a sympathetic registration surface, accumulating movements and glances that feel immediate and close by: a ringside view of modern life in absinthe-soaked freefall. In the brothels, Lautrec saw the spectacle of the circus and the ribald choreography of the cabaret dance replaced with routines of inspection, whether the prostitutes’ own, attending to their hygiene, or the invasive ritual examinations of regulators and doctors. Scrutiny is a constant in this life, where failure to comply, or to be compromised by disease, almost certainly meant arrest.

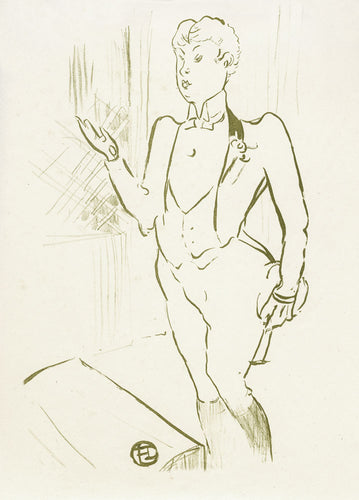

Clownesse Assise, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Not only did the women of the brothel have to endure the indignity of moral and medical scrutiny, they had to turn this scrutiny on themselves, for all the while they are surrounded by mirrors and reflections of their own nudity. In this overwhelming cycle of attention, they stood for every woman plagued by her own image. ‘A woman must continually watch herself,’ John Berger famously wrote in Ways of Seeing. ‘She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself…From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually. And so she comes to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity as a woman… Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at…The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.’

La Toilette, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

In Elles, surveying is the central theme, except that this surveillance has physical implications: we know that sight will lead to touch. And we mustn’t forget that like Délacroix, like Flaubert, like Baudelaire and countless other artists before him, he was a client of his subjects as well as their chronicler, eliding the role of muse, lover, courtesan and sex worker in a single, complex amalgamation. He invited them to dinner, to the theatre, to the cabaret, and drew them watching and observing others, and, apparently at ease in his presence, they revealed to him their own secrets: their lesbianism, closeted or otherwise, the complications of their sexual cohabitation, episodes of self-love, and the dreams and desires denied them by their status.

Elles does not disclose the intimacy of these relationships; only the access Lautrec was allowed to document the brothel sorority and its idiosyncrasies. In the title image and the depictions of exhausted working girls spread out on their unmade beds, many seem desperately young. In the two depictions of the older Juliette Baron, madame of the brothel in the Rue des Moulins, attending her daughter, Paulette (Mademoiselle ‘Popo’), age and years of exploitation having taken their toll and relegated her to an administrative role. Unlike Manet’s Olympia, or his Nana (both modelled by courtesans), few of these women stare out at us and most are consumed in moments of intent solitude, even in the presence of a waiting john. Cha-U-Kao the circus performer, her name a pun after the ‘chahut chaos’ dance (the ‘wild rumpus’), is the only subject in the series who is not a prostitute, and coincidentally the only one to return our gaze. The look she gives us is indistinct but somehow resigned, fatigued, despite the corners of a smile: she is as much a victim of spectacle and scrutiny as the anonymous prostitute bent over her basin and washing her back. She looks down to the sink and her hand, applies the sponge to her shoulder which is turned towards us (as most are in the series). We cannot see her eyes. Above her, prints on the wall suggest the mood and activity to follow. Otherwise modest, her breasts are betrayed by the reflection in the mirror in front of her. Lautrec is making us look from all angles, showing us images within images, triangulating our gaze as Degas did with his own bathers: his subject has nowhere to turn and escape it. Incidentally, the two artists did occasionally meet. Lautrec lionised his elder, but when the notoriously guarded and bad-tempered Degas saw the Elles lithographs for the first time, he evidently felt he had let Lautrec get too close. ‘He wears my clothes,’ he is supposed to have said – ‘but cut down to his size.’

Couverture, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Elles sold poorly on its publication. Limited to 100 copies, each portfolio priced at 300 francs, they were not prohibitively expensive, but they were certainly more than had ever been asked for Lautrec’s prints which normally cost – to use the usual conversion rate – little more than a round of drinks at the Moulin Rouge. Denounced by the occasional reactionary critic as ‘filth’, the series was initially met with silence. It was not as if nudity – explicit, borderline pornographic nudity – was especially rare in bourgeois homes; far from it. The likes of Henri Gervex, Paul Chabas and Félicien Rops all had their place in contemporary collections. Ironically, had Lautrec been more salacious in his series, had his subjects been more overtly nubile, he would probably have been more successful. His prints were disregarded as indecent by the very nature of their decency, their measured indifference in exposing the routines of a clandestine industry.

Instead, in opening up the maisons closés, Lautrec was deemed to have committed a double crime. Not only had he failed to charm or to titillate, he had broken the unspoken bourgeois covenant that a woman’s promiscuity should be simultaneously serviceable and shameful: that one could, to paraphrase Berger again, ‘morally condemn the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.’ Lautrec’s lack of judgement for the prostitutes was perceived as a silent judgement of their clients. As the art historian and curator Michel Melot put it, ‘what [Lautrec] looked for in the brothel was neither the extraordinary nor the merely sexual but the everyday life of the pariah. He did not seek to depict erotic scenes as did Rops; his aim, on the contrary, was to rob the venal adventures of the middle-class of their mystery by showing that real people existed behind the make-up.’

Deux Femmes, Elles, 1969, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

In time Elles was seen for what it was: not just a lithographic feat, but a series of images in which the seed of 20th century modernism can be seen and felt. Original lithographs from 1896 are now prohibitively expensive for most: a full suite recently fetched over $1.5 million at auction. But in 1969, a year confronted with its own challenges to sexual mores, the Toulouse-Lautrec Circle reissued the series in the edition of 1,250 copies which is illustrated here. If the walls of the Rue de Moulin brothels could talk, what would they say to us today? Of the hidden cameras and camera phones with which we surveil ourselves and others? Lautrec famously dressed up and played to the camera, but he had a world of wealth to retreat to that the brothel girls did not. It is worth remembering that his success in Elles was, for them, just another day at work.