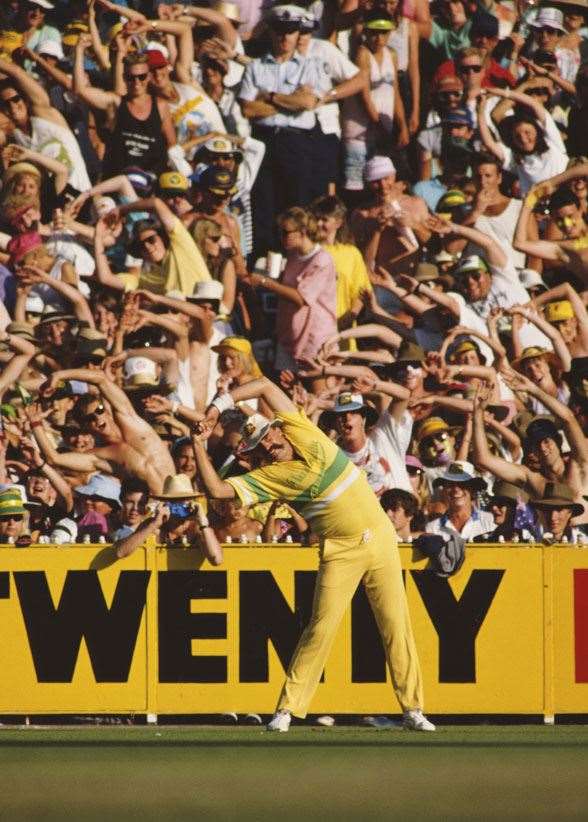

Enjoy a few beers with this proud Victorian.

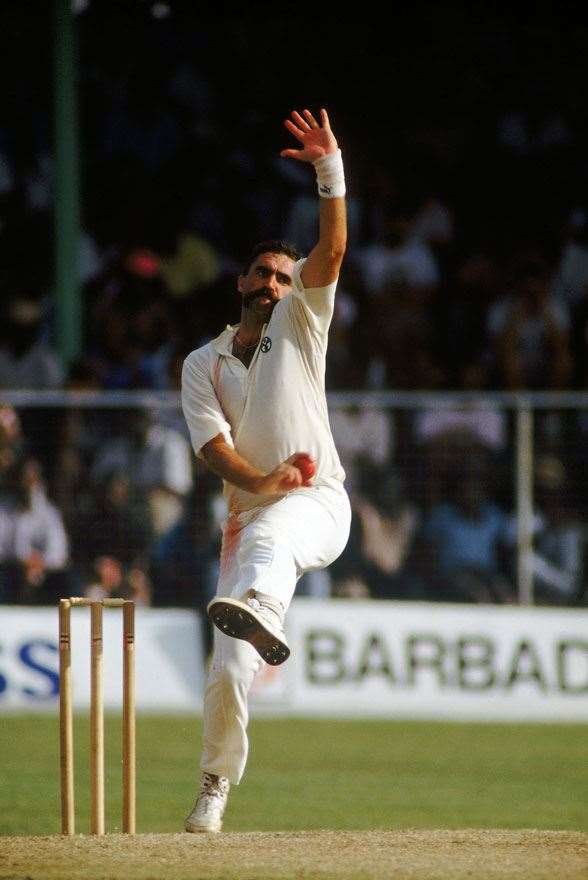

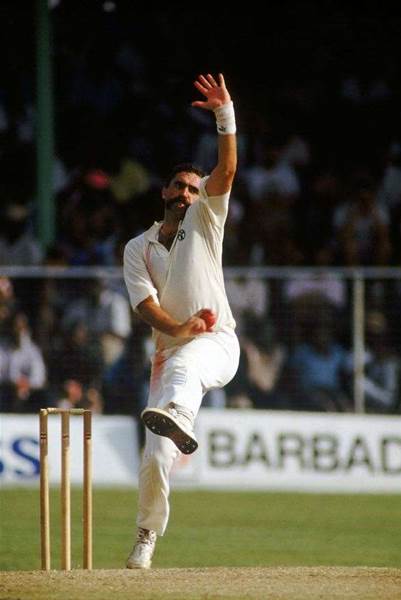

The big Victorian with the bushy handlebar mo storming in from his marathon-esque run-up: would there have been a scarier sight for the batsmen of the world than that?

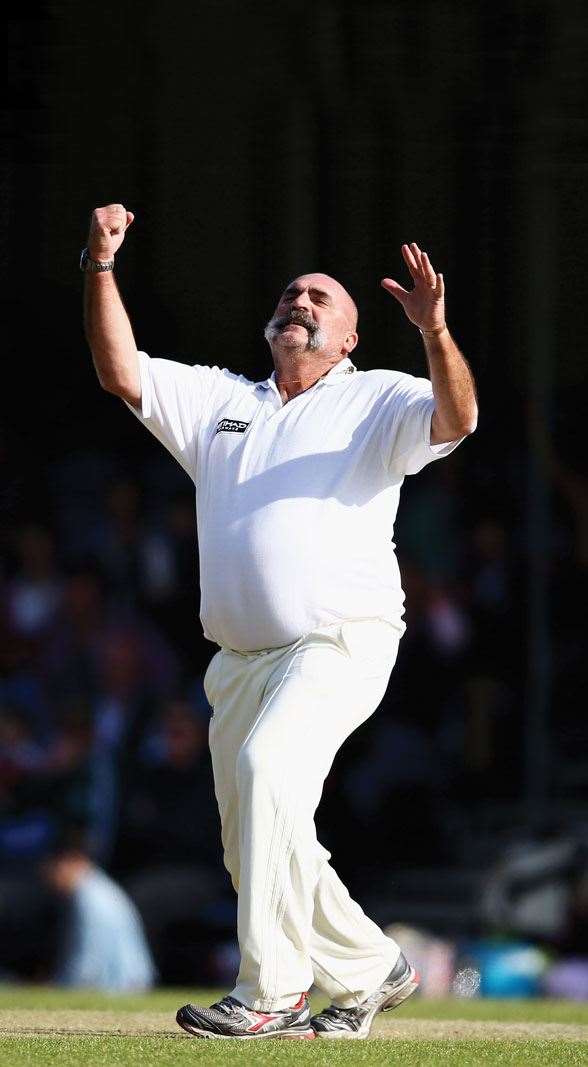

Probably not, as the right-arm fast bowler’s career record shows; a grand total of 212 wickets across 53 Test matches between 1985 and 1994. Ferocious as a player but full of heart and team spirit, he took 38 wickets in 33 ODIs in the canary yellow, too, with plenty of batsmen around the world no-doubt celebrating his decision to call it a day when he’d had enough ... Pommies, mainly, especially those among his career-best haul of 31 wickets on Australia’s 1993 Ashes Tour of England. A lot of those gentlemen appear in Merv’s newly released book: 104 Cricket Legends, in which he outlines his reasons why each of his subjects deserves the much-sought-after tag. There’s also a cheeky anecdote about each one, too. (The larger-than-life Merv even promises that some might be true.)

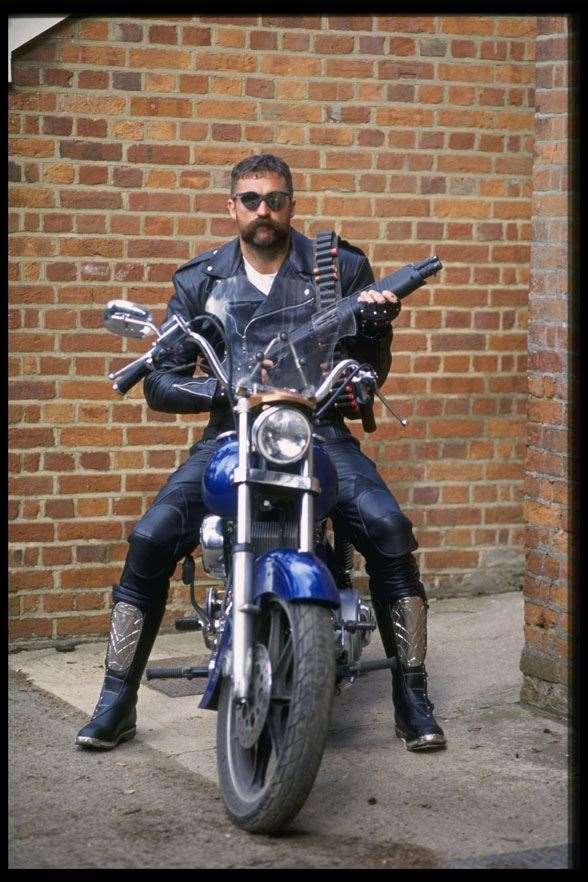

In a past life, post-playing, Hughes was a national selector, and these days is a vital cog in Australian Sports Tours’ fan transportation to places like the West Indies and the Old Dart, where Hughes will be required throughout 2015. Can you imagine a better host than the Fruit Fly? (He was dubbed that for his status as Australia’s biggest pest). We can’t, which is why we sat him down for a yarn as the Cricket World Cup swings into action.

Your new book is called "104 Cricket Legends" – did you have to call anyone you left out to say sorry in advance?

Nah, but a lot of people do ask, “Why 104?” My standard answer is that I’m giving people four per cent extra for Christmas or whatever. In fact, 104 was my ODI cap number, so personally it’s significant. Also, 104 just intrigues people; makes them ask why. There were no intentions of upsetting anyone. Even the guys who I wrote about, this is just my view of them as team-mates, competitors and as blokes who had an impact on the game of cricket – even the players I’d never met. How it all came about was that a good mate of mine, he’s a cricket tragic. We’d be watching a game on TV and something would come up about David Boon, so I’d find myself telling a story about David Boon, and we’d have a bit of a laugh about it. And then something would come up about, say, Richie Richardson. We’d just keep chatting and he’d say, “You should put this is a book.” And I’d ask, “Well, who’s going to want read it?” And he’d say, “This kind’ve thing is interesting to people.” The book is a behind-the-scenes look, it’s not just facts and figures. If anyone has missed out, then it’s not a deliberate ploy; they’ve just missed out. You can only pick 104 legends, can’t you?

You were a more-than-handy Australian rules player as a kid, so what made you choose a cricket career in the end?

A lot of people don’t realise that, across all the states, cricket loses probably seven of its top ten most-talented players to other sports. This is especially so in Victoria, where we often lose our top players from the 17s to the 19s to football. In my case, I’d just started training down at Geelong when I was first picked in the state cricket side; I was probably picked before I was ready. Other blokes like Simon O’Donnell, Jamie Siddons, Tony Dodemaide and a little bit later Damien Fleming were all entering state cricket at the same time. I dare say there were a few others of the era who were contemplating going into football. It was just a bit of encouragement that kept us all in cricket.

What do you remember most about your first day in the Australian sheds?

It was a time of change for the Australian team. For example, my debut was Bob Simpson’s first game as coach. So he’d come on board, Allan Border was captain ... Ray Bright played; I played a lot of club cricket with Ray, played state cricket with him too, so to have him there was a bit of a buffer. While I’d played against a lot of the older blokes, I didn’t really know them that well. It was a pretty new team; a lot of the guys in it were very young and just finding their way. Geoff Marsh and Bruce Reid also debuted in that Test match. It wasn’t as if you’d just come in to an established side and you’d pushed one of their mates out. There was almost a revolving door there for a while, where guys were coming in and going out; I played the one Test and then was 12th man for the next Test while Steve Waugh came in. At the time, I was wide-eyed and really didn’t know what to expect. The Test match was a draw, Sunny Gavaskar got about 160 not out. I just remember how tough it was. Definitely a couple of rungs up from state and first-class cricket in Australia.

Your long, angled run-ups were famous; sometimes they were up to 45-50 metres. Was that a speed-generating method or just how you rolled?

Each to their own. I just felt like I needed it. When the over rates came in, and they were policed more heavily, you sort’ve had to watch your run-ups. I think in my first Test, while I had a fairly long run-up, I had shortened it a fair bit. Some people are momentum bowlers ‒ they need momentum through their run-up to get through the crease. Other blokes are just strength bowlers who can virtually run off six-seven steps. I’d run in on an angle, where I’d be almost bowling across the front foot. If I ran in a straight line, because I used to flay my front foot out towards the offside, it would give me a lot of back trouble. I found if I ran in from the angle, then flayed the front foot out, I was pointed at the target and was putting less pressure on my back.

Was your jovial nature out in the middle a conscious tactic to keep the mood light in those pressure-cooker situations?

I don’t think it was a conscious tactic. I was brought up to express my feelings; if you’re having a good time, let people know you’re having a good time ... Certainly playing for Australia, I had a good time. It was also a little bit of a nervous reaction as well. When I get nervous, I get a little bit boisterous and sort’ve carry on a bit. So a case of nerves more than anything else. But also just trying to enjoy myself. If you take your sport too seriously, you can put unnecessary pressure on yourself.

What’s the cleverest or most biting sledge you heard from the crowd over the years?

One of the best I heard was over in Perth. Against the West Indies. Viv Richards got 156 and we really didn’t have any answers to him. There was a four hit down the other end. Tony Dodemaide was at third man and I think I was at fine leg. Tony ran up and said to AB, “A bloke down there reckons Viv has a weakness.” And AB turned around and said, “For crying out loud, just tell me, what is it?” And Tony said, “The bloke reckons it’s kryptonite.” So we had a little bit of a chuckle over that. You hear isolated things from the crowd and some of them are quite funny, but I reckon that was the best one.

Who did you find was the hardest batsman to get out?

Early in my career, Sunny Gavaskar. I think I only played one Test match against him and didn’t even look like getting him out. As I said, he got 160 not out. Viv Richards was brutal. They’re two different types of players, one was attacking, brutal, and the other was death by a thousand cuts. Gavaskar just used to nick you around for ones and twos and if he got a bad ball, he’d hit it for four. Viv was just brutal. Later in my career? Sachin Tendulkar and Brian Lara, but also Michael Atherton of England was a superstar. He was probably the most competitive bloke I played against. He was a ripper, and at a time when England wasn’t doing so well against Australia, his record against us was very good.

You went to bed on a Test hat-trick against the West Indies in the 1988-89 series in Perth, which, oddly, you actually claimed across three overs. How were the nerves that night?

I didn’t even know I was on a hat-trick! So basically, West Indies batted first in the Test match. I got Curtly Ambrose out. On the first ball of my next over, I got Patrick Patterson out to end the innings. That was the match where Geoff Lawson got hit. We went out to bowl; we had probably five overs to bowl from memory late on the third day, and I got Gordon Greenidge with the first ball of the innings. Everyone said that I went over the top in my celebrations, but, again, honestly, I didn’t know I was on a hat-trick. Basically, there was a bit of tension and feeling around because of what had happened to Geoff Lawson, so we were just pretty happy that we got the wicket. Steve Waugh came up at the end of the second over to grab my cap and jumper to take it to the umpire and he just said, “I think you got a hat-trick.” I said, “Oh, I don’t think so.” And he went through it: “What about this ... ” etc. I said, “How do you know all that?” He said, “Um, we just heard it on the PA system.” So I thought, oh well, happy days! But at the time, I didn’t know I was on a hat-trick.

If you had to write the user guide to being a national selector, where would you start?

There are probably two major points. Number one is to remove state bias. And number two is that you can’t afford the luxuries of hindsight, speculation or sympathy. You have a job to do, and you do it. I suppose the silent motto from

the selectors at the time was: pick a side to win today, with a view to tomorrow. So if you have 11 blokes who are all around the same age, that’s okay for now, but down the track you’re going to lose a heap of players together. You can’t afford that. You have to have younger blokes coming in as the older blokes are going out. You have to have different levels of experience in the side. That was the simple view that we had. Yes, every game we play is very important, but always keep an eye on the future.

As well as your jocular side, there was a lot of aggression in you in your day. When did the sport of cricket go from the so-called gentleman’s game to the all-out warfare of the modern version?

It’s been like that for as long as I’ve played; it was how we played and how I was taught to play: play hard on the ground and off the ground, it’s all left behind. From the hours of 11 till six, it’s business, and afterwards it’s “go and have a drink with the bloke next door”, who is basically thinking and doing the same thing. Cricket was played pretty tough through the ‘60s and ‘70s. I suppose Rod Marsh, Ian Chappell, Dennis Lillee went pretty hard at it; I grew up watching those guys. Certainly the education I got playing club cricket was: just be tough and uncompromising. You find out that not everyone plays the same way. In Australia you go around at club level and to the different states and everyone has a different view on how hard or how far you can go. I think it’s been sanitised a bit, which is good for the game. I suppose the simple view is, if I go out and I’m sledging you as a batsman, if you’re more worried about what I’m saying than what you’re doing, then it’s worked.

How did the whole Bay 13 love affair get to the point where you were running aerobics classes for them?

It all started on a rain-affected game at the MCG. We’d batted first and got a big score. Carl Rackemann and Terry Alderman picked up a few wickets. From memory, Pakistan were 4/28 after about ten overs. So they were nowhere. Down at fine leg I got the signal from Allan Border to warm up. I start doing exercises, and there was a bit of a roar behind me. Every time I looked around there was nothing going on ... I bowled my first over and Dean Jones came across and asked, “Do you know what’s going on down there?” I said, “I got no idea.” He said, “Mate, every time you do an exercise, there’s about 12,000 people behind you doing the same exercise!” So I just had a bit of fun with it.

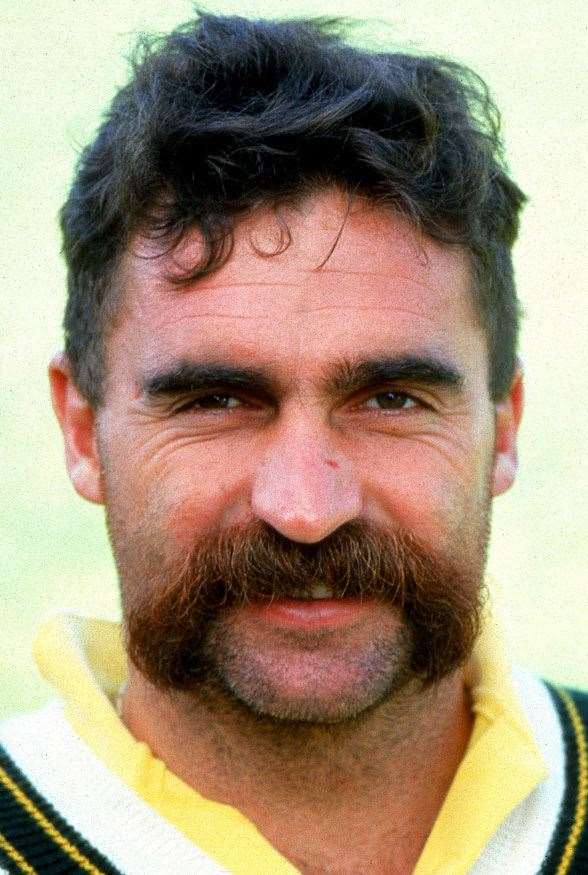

When did you discover that a mo looked pretty cool on you and that you were going to run with it?

It came about through laziness more than anything else. A mate from Werribee and myself did a trip around Australia in 1985. An extra cost was shaving cream and razors. We learnt that pretty quickly, so they went out the window. Same with haircuts, so we’d been gone for probably five months, got back home, had hair every where, had a full-grown beard. I went in to get a hair cut and a shave. They shaved my head back, shaved down my face and they actually left the moustache on; I don’t know why they did it. I thought this will be fun for a little while, bit of a stir. Not that cricketers are superstitious, mind you, but we like things the way they are, especially if things start going well for us. When I got back from that trip, ’85-86, I started bowling well. I haven’t been game to shave it off since. These current players have to realise that facial hair does enhance your performance.

So the Cricket World Cup has just commenced. Who do you see lifting the trophy at the end and who is your smokey?

It’s going to be a tough one. The side that has a little bit of luck and no injuries will win it. Australia and New Zealand are going to be hard to beat because it’s their home turf. But gee, India is a good side, they seem to be plucking good batsmen out of the air at the moment. Sri Lanka are always going to be a danger. South Africa are going to be tough. Pakistan and the West Indies are unpredictable. If it’s a knockout game, those two teams are very hard to beat, but when they have to rely on being consistent, they both seem to struggle. But they have a lot of talent. Gee, semi-finals? It’s hard to go past Australia, South Africa, India and Sri Lanka. And then it’s anyone’s.”

Related Articles

Luck of the Draw

Harman hails lookalike Ponting as 'handsome fella'