"There really is something otherworldly about the tuna," says journalist Karen Pinchin. She went on a years-long, globe-spanning journey to understand this top marine predator. A warm-bodied fish, bluefin tuna have a physiological mechanism that prevents them from losing heat through their gills, allowing them to travel insane distances. Amelia, the fish at the heart of Pinchin's book, Kings of Their Own Ocean: Tuna, Obsession, and the Future of Our Seas, was first tagged off the coast of Rhode Island. More than a decade later, Amelia showed up in the Mediterranean, having swum all the way across the Atlantic Ocean.

KCRW: The charter boat captain Al Anderson in Narragansett, Rhode Island has a very unusual business model: He catches bluefin tuna off the New England coast, puts plastic tags on them, then throws them back in the ocean. He's tagged something like 60,000 fish. Why does he do it? And why has it made him so many enemies?

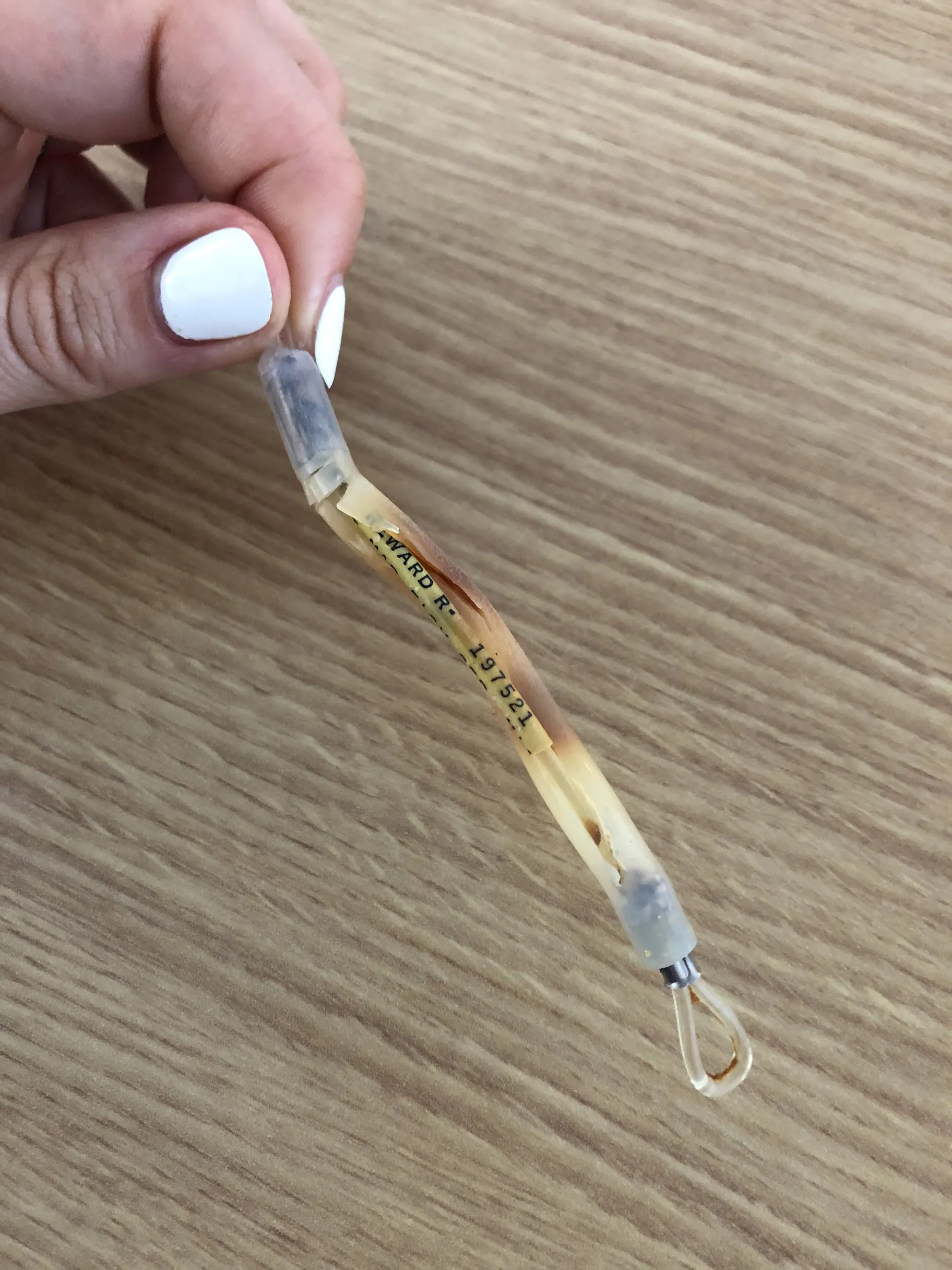

Karen Pinchin: He's the protagonist of the book, and he's kind of the beating heart of the story. He passed away in 2018 but he was a charter fisherman. He would take anglers out and they would catch tuna. When the stocks collapsed, when the population of Atlantic bluefin tuna started slumping and the US government essentially put a moratorium on catching this fish, he said, "Well, I'm going to tag fish for science, catch the fish, treat them extremely gently, and set them free with these plastic spaghetti tags." They actually look like little pieces of orange or yellow spaghetti embedded in the back of the fish. It's one way for scientists to start to understand, “Where are these fish going? Where are they breeding? How do they migrate? What's the health of the population?” And in his lifetime, he tagged more than 5,000. He would call them footballs. Juvenile bluefin tuna actually have the shape of a football.

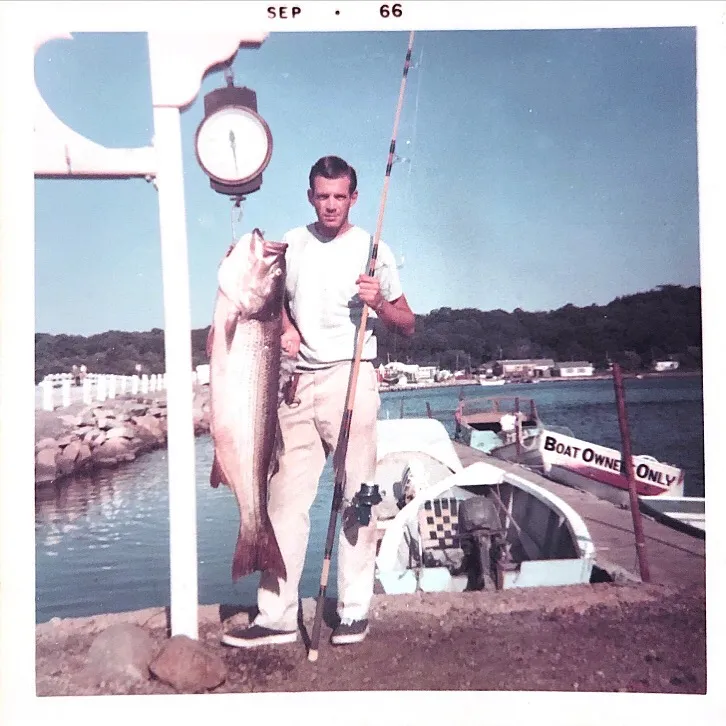

Al Anderson poses with a striper in the 1960s. Photo courtesy of Dutton.

He also tagged and released one particularly famous fish, Amelia. What is so special about her? And what does her journey tell us?

In some ways, it's kind of Al's story and Amelia's story intertwined. She was tagged in 2004 by Al and retagged three years later, which is quite rare, by a bluefin tuna scientist in Massachusetts. Then 11 years later, she shows up in the Mediterranean. She has traveled across the entire Atlantic Ocean. She has spawned on the European side, where these fish are essentially not supposed to mix. You're supposed to have the American fish, the Canadian fish, and the European fish, and they're supposed to kind of stay where they are. But this fish, she was caught in 2018. I found out about her in a call from the bluefin tuna scientist who said, "Finding this fish, these three data points, it's like Christmas. It's a needle in a haystack, the likelihood that this fish would have crossed.” But that fish is joining this cohort of bluefin tuna who are crossing back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean. And that tells us something about the health of the species that we didn't know before.

This plastic tag was embedded in the back of a tuna dubbed Amelia, who was tracked for 14 years and named after Amelia Earhart and her multiple Atlantic crossings. Photo courtesy of Dutton.

I understand that learning about Al's work was the impetus for writing your book. Or did you have a fascination with tuna and fishing long before then?

I grew up catching freshwater fish with my father, who was also a pretty complex guy, in rural Ontario. I joke in the book that I learned how to get a fish before I learned how to blow dry my hair or do my nails. I was a bit of a tomboy. The first time I saw a bluefin tuna, I was actually working for a small restaurant up here in Canada, and touching it, running your knife along its spine, having that sense of reverence for the fish, there really is something otherworldly about the tuna. It planted the seed for what became a world-spanning, genre-spanning adventure for me. My husband didn't know what hit us. All of a sudden, I was traveling to Spain, I was traveling to Japan, trying to answer this question: What is this fish? What does Amelia mean? Ultimately, what is our future of eating seafood on this planet? So, you know, not ambitious at all.

Journalist Karen Pinchin became interested in bluefin tuna after becoming obsessed with a single fish called Amelia. Photo by Matt Horseman.

Let's talk about bluefin tuna. They're not just another fish. You describe them as "more machine than fuel, more predator than prey." How big are they? And how do they compare to other kinds of tuna, like yellowfin and albacore? What should we know about them?

One significant fact about bluefin is this kind of fundamental element of evolution, in that it is warm-bodied. It has a system called a rete mirabile. It's essentially like a heat pump. As it breathes, the system prevents the fish from losing that heat through its gills, so it can keep its brain warm, its eyes warm, its muscles warm. That allows it to travel these insane distances.

One fish that I write about in the book traveled about 10,000 kilometers in 15 days like this. They were able to track this underwater through tagging. That's like doing five marathons a day, for more than a month. That's how fast these fish are. That's the challenge for figuring out where they are in the ocean.

The largest tuna ever caught was close to 1,500 pounds, if you can believe that, off the coast of Nova Scotia. I compare it to the weight of a grand piano, if the grand piano was shaped like a nuclear weapon. This is a meters-long fish. I've talked to numerous fishermen, and I document this in the book: If you're hit by the kicking tail of one, you can break ribs, you can break bones. Fishermen in Spain often get tiny little cuts an inch or more deep from the little spikes that are along the fish's tail. It really is a predator. It's a top marine predator and its physiology reflects that. Ernest Hemingway said that if you could catch a fish, you were essentially communing with the very elder gods. I think to see one in person is quite remarkable.

Tuna fishing is roughly a $40 billion industry, and it keeps growing every year. When did the demand for this particular kind of tuna kick into high gear and what trends continue to drive it?

It was kind of post-World War II, after the Americans had been in Japan. You really saw this widespread acceptance of bluefin tuna as sushi, as sashimi in Japan. This is documented beautifully by Trevor Corson in his book [The Zen of Fish]. You had this demand in Japan, and all these fish, particularly off the eastern coast of North America. There was a day, August 14, 1972, that is still referred to as the Day of the Flying Fish in what is now the Toyosu Fish Market in Tokyo. That was the day that the first tuna were successfully packed into wooden coffins filled with ice in rural Canada on Prince Edward Island, home of Anne of Green Gables. Those coffins were put on a truck and shipped to JFK. They were loaded onto a cargo plane that had just dropped off VCRs and Japanese electronics, and those fish were flown to Tokyo and sold for an amount of money that hadn't been seen before for a fish that hadn't been caught in Japanese waters.

So once we had the refrigeration techniques, once we had the transportation, this is where you see globalization and capitalism and the commodification of fish. It really kicks into that higher gear. It's no coincidence that's when the numbers of Bluefin in our oceans started to dwindle.

August 14, 1972 is still referred to as "the day of the flying fish" at Toyosu fish market, and marks the day that the first tuna were successfully shipped from JFK to Tokyo. Photo courtesy of Dutton.

Tell us about the darker side of tuna fishing. You've said that stocks are coming back. What has been put in place to allow that to happen? Is it that bluefin tuna ranches put less pressure on wild stocks? Or is it jurisdictions going after illegal operations and fisheries? What has happened to make the change?

This is one element where all the work by environmentalists, namely Carl Safina, to put that international pressure on countries, even on restaurants, to really [ask], where are these fish coming from? Ask your local restaurant, you know: Is this a rod-and-reel caught fish? Is this a harpoon fish? The amount of work that's happening at the international level is inspiring. You have these young, in some cases predominantly female, activists who've spent their entire careers trying to make it so the regulations and the quotas are science-led.

The other element is climate change. Physiologically, the bluefin is remarkable. One of those remarkable features is that it needs warm water to breed. That's where it spawns in the Gulf of Mexico off the United States, in the Mediterranean off Europe, and there's one new spawning ground that has been identified off the slope sea off the Carolinas. This is one of these strange stories where the bluefin, because it has this remarkable body, it makes it resilient to climate change, which is great news. It's a good news story. But it's also a reminder that as the oceans warm, we're starting to see these knock-on effects. By no means do I say, "Eat all the tuna you can." It's just that in terms of a moment in history, now is a pretty good time to be a sushi eater.

Kings of Their Own Ocean: Tuna, Obsession, and the Future of Our Seas explores the story of bluefin tuna, one of the top predators among fish. Photo courtesy of Dutton.

What happens if bluefin tuna, or all tuna, disappear? How would that impact the food chain?

That is honestly, my worst nightmare. It's biologists' worst nightmare because we have these extremely beautiful, finely tuned natural systems. Nothing happens by accident in these systems. The bluefin tuna is eating an enormous amount of forage fish and smaller oily fish and squid. All those smaller fish have their own knock-down effects on their ecosystems. The really scary thing is that we just don't know, nobody knows.

I talked to quite a few environmentalists who say, they're much more worried about other species. So if we can eat it in moderation, if we can be thoughtful, if we can make sure we're not eating longline-caught bluefin… there's a big difference between a bluefin that's been caught on one fishing rod or harpooned with one harpoon than these lines that get dragged for miles and miles throughout the ocean. I think now what we need is, what if we were to treat the whole ocean this way? All these species that aren't quite as glamorous, they're not charismatic megafauna the way that that a Bluefin is.

What is the connection between the cult the Moonies and this fish?

Reverend Sun Myung Moon, the founder of the Unification Church cult or the Moonies, became obsessed with bluefin tuna when he moved to America. His vision was to start this empire, essentially this religious kingdom, based on bluefin tuna, based on catching them, selling them, making money, having a whole fleet of boats. I interviewed the captain who actually started this bluefin tuna initiative and the wildest part of the story is that it actually worked.

The bluefin tuna industry, as it was developing in the early '70s, these Unification Church boats, they weren't even fishing from big boats, they would just have hand lines in dories. They would catch the tuna and then the tuna would just pull them around in these eight meter boats until the fish got tired. Then they would pull them up and they would bring these fish aboard. And they would ship them to Japan and sell them for thousands and thousands of dollars. Eventually, they started their own refrigeration facilities. They started their own sushi restaurants. The acolytes spread across America and to this day, the majority of sushi that is sold, of raw fish, is sold through Unification Church-affiliated businesses.

Are they still fishing? Or are they now just involved in the middleman activities?

They're largely involved in the middleman activities but they do still run major boat-building facilities. So [they're] still very integrated, particularly into the northeastern fishing industry and maritime life. Once you know to look for it, you'll see it everywhere. So you're welcome, and I'm sorry.