Review: LACMA reopens with six shows that hint to what the future museum will be like

As visitors venture back to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, shuttered for a year because of COVID-19 and reopening Thursday, they will find many changes.

Some, but not all, are a result of the pandemic.

I visited during members’ previews. That afternoon, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told reporters that she felt a sense of “impending doom,” given sudden infection spikes. That gave me pause.

To protect patrons’ health, familiar precautions are in place at LACMA. Ticket reservations made online or by phone are necessary to keep attendance at reduced levels. Masks are mandatory, health screening (including a temperature check) and contact tracing data are required, and traffic flow directions are in place inside galleries. Exhibition text panels have been replaced by QR codes.

I found none of it onerous. Getting the reservation was easier than snagging a COVID-19 vaccination appointment not so long ago — although the online-or-phone requirement for a reservation would be a stumbling block for anyone without access to either.

One guard cheerfully greeted, “Welcome back.” Another barked, “Where’s your reservation?” — an odd papers-please request after jumping hoops for admission right outside the door. Most visitors were following the rules.

Beyond essential pandemic alterations, however, the museum’s other changes were optional. If you haven’t been down Wilshire Boulevard’s Miracle Mile in the last year, be prepared for the complete disappearance of LACMA’s four buildings dating from 1965 and 1986. They fell to the wrecking ball just as quarantining began, hauled off to a landfill in Eagle Rock to make way for the new building, the David Geffen Galleries, under construction to house the permanent collection.

Six new exhibitions — four in the Resnick Pavilion and two in the awkwardly named Broad Contemporary Art Museum building — have been installed. Together they give two clear indications of what to expect the new LACMA will look like, once the Geffen Galleries open.

One is a sizable theme show built around art in LACMA’s encyclopedic collection. Rather than permanent displays organized by the art’s chronology and geography, the Geffen Galleries will show the collection as changing theme exhibitions in seven exhibition halls.

The other is an emphasis — actually, overemphasis — on contemporary art. Five of the six shows feature art made since about 1960.

That raises the question: Given the city’s Museum of Contemporary Art, the UCLA Hammer Museum, the Broad downtown, the Institute of Contemporary Art, the California African American Museum, college outposts including the Vincent Price and Benton museums, Lancaster Museum of Art and History, Torrance Museum, myriad nonprofit spaces like LACE, the Armory and LAXART, plus a large and lively gallery scene — and more — do we really need LACMA to be top-heavy with contemporary art?

I understand that’s where the money is. But, according to the LACMA website, since 2017 more than 80% of the exhibitions have showcased 20th and 21st century art. LACMA is the only encyclopedic museum the city’s got. The long pandemic closure is over, but the health crisis isn’t the only reason that I’ve missed the place.

The theme show is “NOT I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE),” with around 200 works, major and minor, selected across global cultures past and present (on view through July 25). The theme is ventriloquism — the art of speaking without moving your lips to make it look as if your voice is coming from elsewhere.

As an entertainment, the show is less Shari Lewis’ Lamb Chop than the disembodied chattering-mouth of Samuel Beckett in the writer’s frantic 1973 stage play “Not I,” which provides the title. Beckett followed an elliptical path in a rapid-fire, 15-minute monologue to ponder what makes up a person’s conception of the self.

The show ends with a BBC video clip of a Beckett performance starring Billie Whitelaw’s motormouth. It opens with a 1992-93 Ann Hamilton video of a mouth full of marbles. In between, 10 sections consider sub-topics like artists’ images of puppets, animals as human surrogates and sound as a visual subject.

Philosophically minded but hardly frantic, LACMA’s “NOT I” is a meta-show — an art exhibition about making art exhibitions. It repeats the truism that art museums aren’t neutral. Curator José-Luis Blondet is the invisible ventriloquist, speaking through the selection and juxtaposition of mute objects.

What he has to say is often eloquent and always informed, although the show feels incomplete.

Take pipes. A display case features a lineup of 10 of the smoking implements drawn from a variety of world cultures, past and present. They include ancient Colima in west Mexico, 17th century India and Iran, 19th century Czech Republic and 20th century Congo and the United States.

Nearby hangs a stolid, 1853 academic portrait of four upper-class white children, primly decked out in velvets and lace, by the popular Victorian New York painter George Augustus Baker Jr. The kids wield pipes, too — pipes for blowing soap bubbles, a common symbol for innocence. The shimmering bubbles signify life’s fragility.

Tucked around the corner and embedded in a carve-out in the gallery wall is a skinny, 8-foot-tall, black-and-white photographic mural by Gordon Matta-Clark. Made in 1971, it uncovers plumbing and electrical pipes of the kind hidden behind the drywall inside any modern building. Matta-Clark’s pipes — in this context a Pop art pun — expose hidden structure.

A room away, in a different section about invisible air, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s brilliant “Soap Bubbles” is a lusciously painted picture of a young aristocrat, circa 1739, leaning on a stone window ledge and gently blowing into a soapy reed. An air-filled bubble expands, threatening to burst. The stone ledge, borrowed from a European Renaissance tradition in posthumous portraiture, implies a meditation on mortality.

All grays, browns and dusty whites, Chardin’s earthy and sensuous oil paint draws your eye to the play of delicate surface textures and soft luminosity across the canvas. The painting gets established as a material analogy for the pictured soap bubble’s fragility.

The splendid Chardin is the kind of first-tier painting that firmly established the symbolic soap bubble that Baker’s impassive American painting later relied on, albeit with far less inventive skill. The Frenchman painted rings around the American.

But the subject matter of wealthy 18th and 19th century youths bearing pipes does evoke the industrialization of tobacco as a primary source for the era’s great European and American fortunes. Kids played with toys while their elders had actual pipes and fancy snuff boxes.

The show’s decorated clay Colima pipe is likely a ritual relic, tobacco cultivation thought to have begun in ancient Mexico. “Old world” colonization of a “new world” — old and new, that is, to the colonizers — is implied if not declared. In this permanent collection installation, very different works of art from very different times and places are talking among themselves.

One absent voice is surprising.

“The Treachery of Images,” the famous 1928-29 Surrealist picture by René Magritte more commonly known by its juxtaposition of a painted pipe with the written text, “This is not a pipe,” is nowhere to be found. (According to the museum, the celebrated painting has been reserved for a Modern art installation opening in the summer.) Its influence on subsequent art is suggested by inclusion of a little 5-inch sculptural copy by Sherrie Levine and a photo by Eleanor Antin.

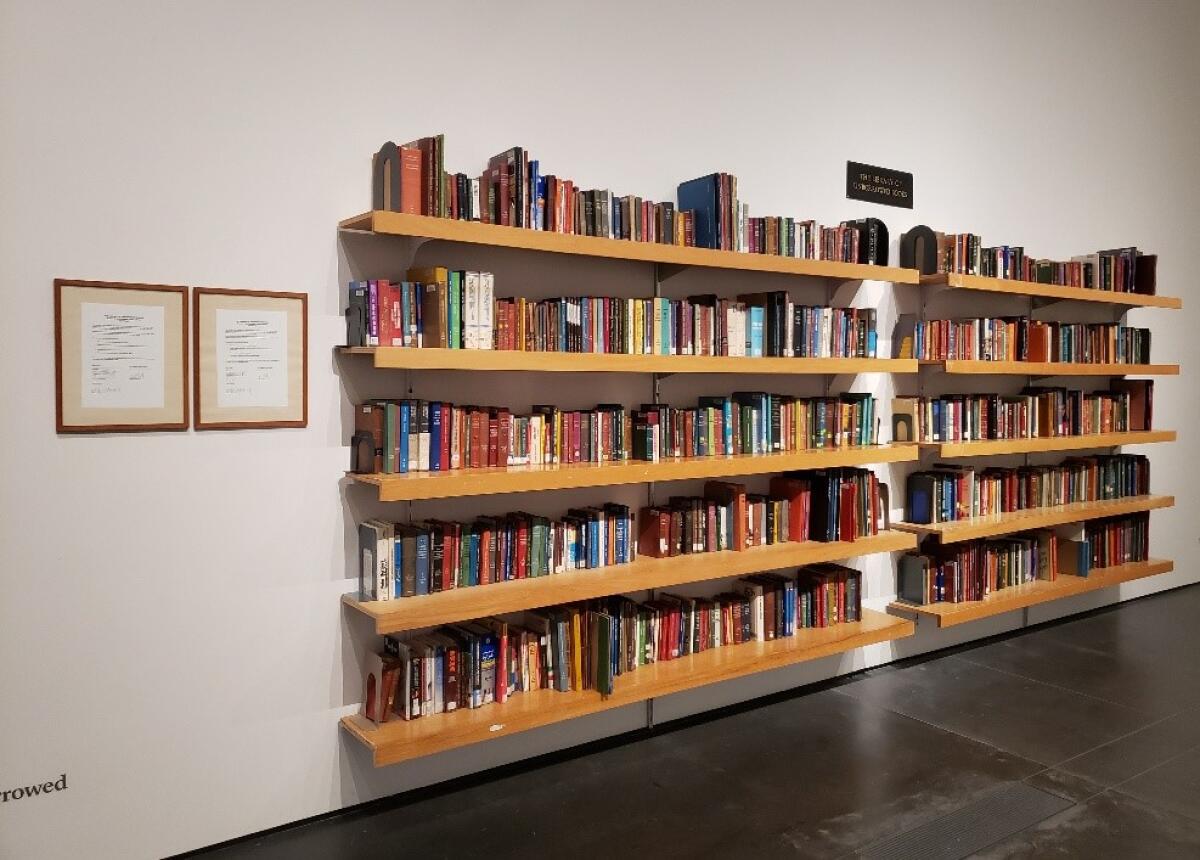

“NOT I” tells a cluster of mini stories. Even the absence of stories is considered, thanks to a clever commission from Istanbul-born, Stockholm-based installation artist Meriç Algün: Close to 1,000 books on a host of topics are displayed on 10 shelves — all loaned from the L.A. Public Library but none previously borrowed by any readers.

The limitation of “NOT I” is that LACMA’s permanent collection is presented as if a group of variously interesting asides whispered by a smart friend. Theme shows are the most difficult to pull off because they beg for persuasive discovery and definitive conclusion. Even with more than 200 objects, “NOT I” doesn’t offer that.

Is any encyclopedic museum collection large enough to accomplish it? Probably not. One virtue of simple chronology and geography as organizing principles for an art museum’s permanent collection is that they’re just unadorned facts without presumption of completion. I left “NOT I” wondering how the David Geffen Galleries might possibly carry it off when surveying everything LACMA owns.

Most of the great objects in LACMA’s long-shuttered collection remain in storage. Japanese, Mesoamerican, South Asian, European Baroque, colonial Mexican, American and more — few are to be seen. But there’s plenty of contemporary art.

German artist Vera Lutter’s 44 pinhole-camera views of galleries and art in the now-demolished LACMA buildings are on view (to Sept. 12) in a show organized by curator Jennifer King. Tied to the minor European and American tradition of paintings that record (and fabricate) the look of mostly royal picture galleries, they offer a bland critique of art museums as an ostensibly shady Enlightenment-era idea.

A big retrospective of middling but popular painter Yoshitomo Nara, 61, is twice as large as it needs to be to account for his market success at branding (to July 5, guest-curated by Mika Yoshitake). Endless, obsessive variations over nearly 40 years on a scowling, wide-eyed little girl adrift in fields of empty space are featured in nearly five dozen canvases, some 700 repetitive drawings and a few sculptures.

Childhood, a common contemporary Japanese motif, has been theorized as representing the infantilization of a once-belligerent imperial society laid low amid the death and humiliation of World War II. Nara’s are like the big-eyed children of kitsch icon Margaret Keane — albeit more skillfully painted and with post-nuclear anxiety replacing greeting-card sentimentality.

Sixteen recent acquisitions of contemporary art are also on view (ongoing), their welcome emphasis on work by women and people of color part of a larger, growing effort among museums to redress past exclusion. Most notable are sculptures by Lonnie Holley and Betye Saar, which add to LACMA’s collection of powerful assemblages that emerged full force in Los Angeles’ Black arts movement after the 1965 Watts rebellion.

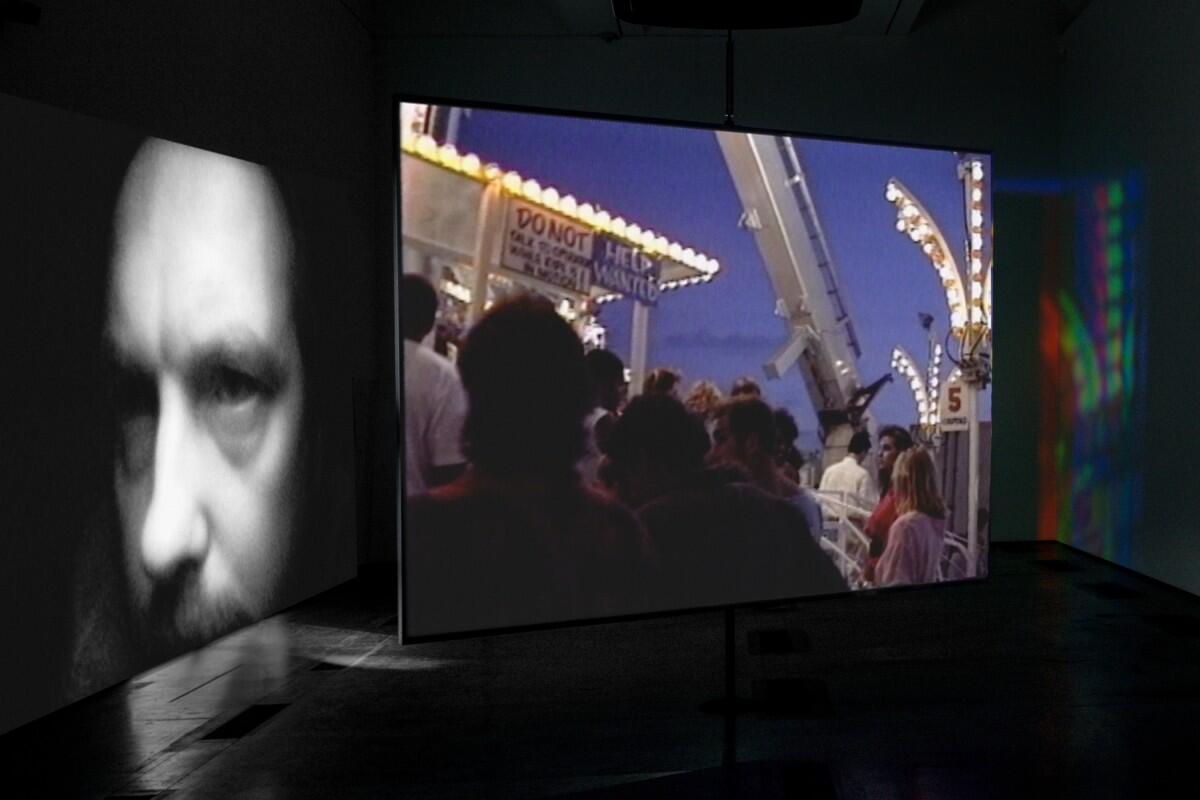

It’s also good to see Bill Viola’s 1992 “Slowly Turning Narrative” (through June 27), an important video installation in the collection by the genre’s pioneer, who is based in Long Beach. Unseen for nearly 20 years, its two projections on a revolving screen, one side mirrored, absorb and reflect illusory fragments of imagery inside a darkened room.

Abandoned buildings, nighttime parking lots, fireworks and more merge with a man’s looming face chanting observations on various states of being. Your reflection gets tangled up in the slipping, sliding image stream as the flow of mediated modern life becomes an enchanted Plato’s Cave.

Consider Viola’s video manifestation of a mind forming fleeting thoughts as a coincidental ancestor to “Give It or Leave It,” a sprawling, visionary installation incorporating film, sculpture, video and stage sets by L.A.-based Cauleen Smith (to Oct. 31). The traveling show, which will be reviewed later, was organized three years ago by Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art.

It’s terrific, but I wonder where most of LACMA’s collection masterpieces went.

LACMA reopens

Where: 5905 Wilshire Blvd., L.A.

When: Closed Wednesdays. Timed reservation required.

Admission: $10-$25; kids 12 and younger are free. Check website for L.A. County resident discounts

Info: (323) 857-6010, lacma.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.