I cover technology at my day job, so I come across the Gartner Hype Cycle quite a bit.

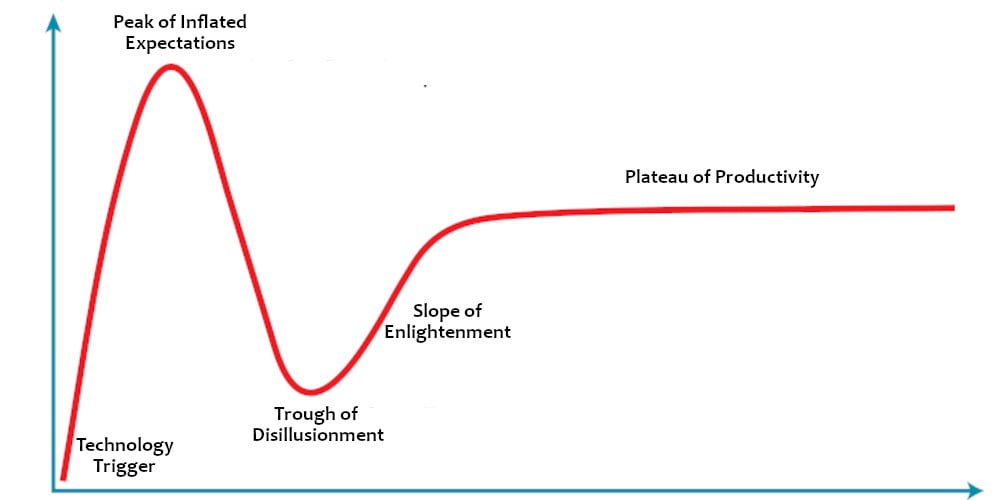

Here’s what it looks like:

The basic idea is that once a new technology comes out, everyone jumps on it, and there’s all kind of hype, some of it unwarranted. Then, as people try to actually use the technology, disappointment sets it, because it doesn’t live up to its expectations. Then a few people are actually able to make it work, others learn from their experience, and, eventually, we settle into a new normal where the technology is a useful part of our lives.

The Gartner Hype Cycle is all about how perception intersects with practical reality.

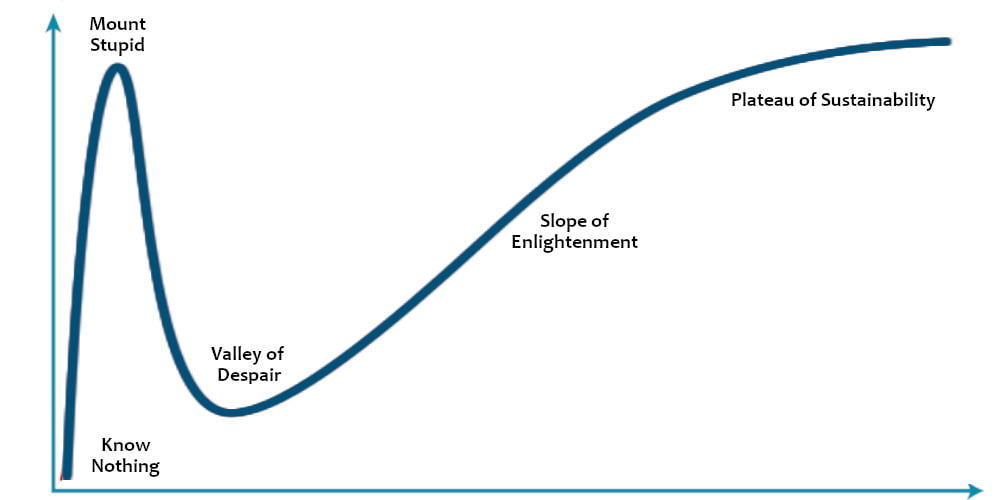

You might have seen a similar curve in an idea known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect looks at the relationship between how much people know and how competent they actually are at it.

In an article last week that appeared on FoxPrint Editorial, publishing industry veteran Tiffany Yates Martin explains how this effect applies to authors. When we first learn how to write, we have just enough knowledge to be extremely overconfident. We think everything we produce is the best thing ever. Then, as we learn even a little bit about what we’re doing, despair sets in. We realize how little we actually know. The ironic thing is that as we move along the knowledge axis, becoming better at our craft, our confidence actually drops even as our skills increase. It can take quite a long time before we regain the confidence we had when we were first starting out. As a result, we face depression, suffer from the impostor syndrome, and might even give up completely.

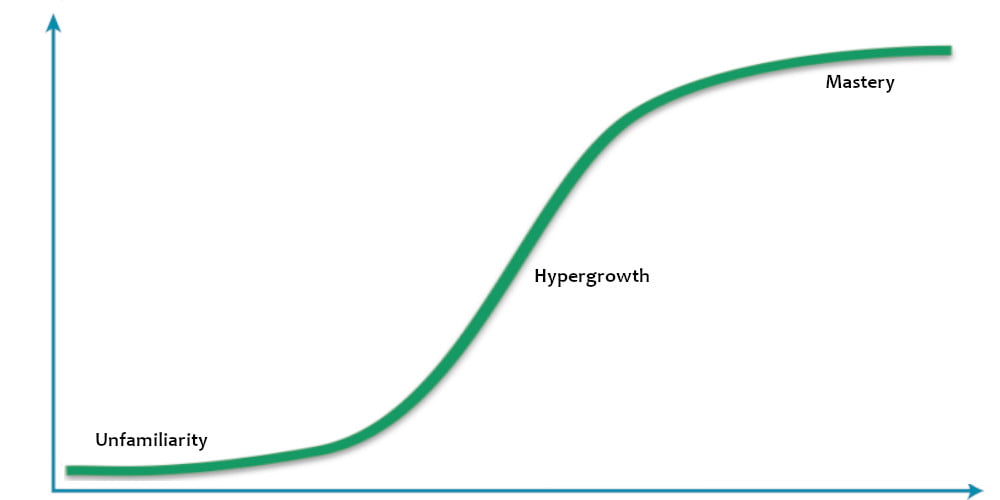

But let’s just look at knowledge, taking out the hype and confidence aspects. Then we get something known as the S-Curve.

The S-Curve, also known as the sigmoid curve, was invented by management thinker Charles Handy back in the 1990s. The idea is that at first, learning builds slowly, then, as we start to gain traction, learning accelerates. After a certain point, when we approach mastery, it levels off again and it becomes harder and harder to improve our skills.

There are two main problems that authors face when they’re on the S-Curve.

First is at the beginning. Even though they’re putting in time and effort in learning, they don’t have anything to show for it. Then, at some point, all their learning kicks in and they start seeing results.

The danger is that instead of focusing on learning one thing, they’ll be disappointed by the lack of results and switch to something else, completely unrelated. Switching just kicks them back to the beginning of the S-Curve again. Or they might decide to hedge their bets, and invest in two or three different, unrelated things. That stretches out that initial flat period for each skill, pushing off the point at which results start to kick in. As a result, by hedging their bets, by, say, doing one series of books as steamy Victorian romance, and simultaneously working on a dystopian hard sci-fi horror, the point at which they get traction for either series gets pushed off into the future — and might not ever come — since there’s little overlap between those two reader segments.

The solution here is to keep the end goal in mind. Focus on the core skills, keep improving them, and trust that results will show up. You can speed up this phase a bit with coaching, technology, and peer support groups, but fundamentally what it takes is deliberate practice. This is a special kind of practice, where, instead of doing the same thing over and over — which doesn’t give you all that much — you instead deliberately focus your attention on improving performance in each area of the skill you’re trying to master. Deliberate practice is hard and painful, but it yields the fastest improvements.

Another danger writers face is at the top of the S-Curve, when progress starts to level off. It takes more and more effort to produce fewer and fewer results.

Some writers panic, and think they’ve lost their touch. They may randomly try different things, stop doing things that have worked, or leave the field altogether.

The solution to this stage is to level up. Look carefully at your skill set, and make a strategic decision to learn a major new skill that takes you in the direction you want to go. That direction might not actually involve improving your core skill. Past a certain level of mastery, the only people who will notice your improvement are other experts. And if you’re looking for market success, you might want to learn a new skill related to marketing and promotion, instead.

As you do so, you will get on a new S-Curve. And, again, initial progress will be slow. It will take time to get through that initial slog. But the result is that you will have a second S-Curve on top of your existing one. The key is to pick your second skill so that it takes you in the direction you want to go, not a random, unrelated skill in a totally different career. Unless you really want to switch careers. In which case, that’s fine — as long as you make the decision deliberately, and not out of frustration.

The role of technology in accelerating the S-Curve

I mentioned technology a few paragraphs back. That’s my area of expertise — I’ve been covering technology in my day job for the past twenty years, most recently focusing on artificial intelligence.

Technology isn’t a replacement for coaching, peer support, or deliberate practice. But it can speed things up quite a bit, often in ways that feel like cheating.

Take, for example, the camera. Artists used to spend years, or even decades, learning how to make realistic drawings. Drawing is hard. Then cameras came along and anyone could get a perfectly realistic image with the press of a button.

Traditional artists stopped focusing so much on realism and went off and launched new movements that involved abstract art, impressionism, and other approaches.

Meanwhile, photography quickly evolved into its own art form.

Today, anyone can take great pictures, and, with photo editing tools, make them look even better with the press of a button.

It opens up the field of visual creativity to everyone. It will still take time and effort to become a great photographer, one who makes money from it, or wins awards. But that initial stage, where you’re unable to produce anything usable, has been all but eliminated.

In music, the same thing happened with synthesizers. It can take years to learn how to play a violin in a way that doesn’t make people’s ears bleed. But a synthesizer can produce perfect notes from day one. It has opened the field of musical creativity to more people. Again, it still takes time to become a successful musician. But that initial period of pain is now gone.

Is it a bad or good thing that the pain is gone? You could argue either way. Some would say that pain breeds character. That real art requires real labor. That a hand-sewn garment is infinitely superior to a machine-stitched one because of the effort involved.

Personally, I don’t think that’s true. I believe in the democratization of art, instead of gate-keeping it, restricting it only to people who put in long, manual effort. There’s nothing wrong with putting in the manual effort, if that’s your thing. Or you could use technology to leapfrog some of the learning curve, and focus your time on other areas. A photographer, for example, could skip the whole dark room phase and take a quick course on learning the latest equipment and photo editing tools, then spend the rest of their time on learning sales and marketing and business management skills. Are they still a real photographer? To me, sure. Old-school photography snobs might disagree, especially if they spent months or years learning to develop film. It’s fine to work with film if that’s what you want. But there’s nothing wrong with going digital, either.

I feel the same way about AI tools. Yes, there are still legal issues related to copyright that will work themselves through the courts. Meanwhile, some companies are already paying artists for using their work in image prompts — or switching to curated training data sets that only include images that they have clear rights to. Once all this shakes out, AI image generation platforms might become a new source of income for artists, instead of being the death knell of the profession.

Consider CGI in movies. The technology has gotten a lot better due to the use of AI tools. But instead of massive layoffs, the visual effects budgets have only been increasing in Hollywood. If you sit through the end credits of any recent Marvel blockbluster, the list of visual effects artists is miles long. The AI will shorten that first part of the S-Curve, get people onto the growth part quicker. But that holds true across the board. If you want to stand out, you’ll need to do more than the bare minimum. Your audience will expect higher and higher standards of visual effects, so talented artists will continue to be in high demand.

I think the same thing will happen with, say, book cover art.

AI platforms will pop up to make it easy to create books covers with AI images. Everyone will use them. The base-level quality of book covers will improve across the board as horrible-looking hand-made covers are replaced by AI-generated ones. But for authors who want something that looks better than the AI-generated average, they’ll need to invest real money to continue to stand out.

Another way that book cover artists can increase their income with AI is by using it to create their own pre-made covers. Today, cover artists either sell their pre-made covers on giant sites, where their work is lost among thousands of other artists, or on their own, dedicated, websites. But there is only so many book covers an artist can produce when working by hand. When customers come to the site they might not find anything they like and leave, never to return. The popular covers will get snapped up first, and the artist will need to take them down off the site, eventually leaving just the poor-selling ones. With AI, they can train a model on their art style and create many covers of the type that sell. They can lower their prices to attract more customers, then charge extra for series covers, high-res images, print and marketing materials, and custom work. And they can use their talent and vision to ensure that their covers are always visionary, always ahead of the curve.

And I think the same thing will happen with books.

Writers are already using AI when writing. They use AI-powered search engines for research, AI-powered grammar checkers, AI-powered character builders. They use online prompt generators and name generators and a multitude of other tools.

For a couple of years now, writing platforms have been offering GPT-3-powered autocomplete functionality. This is where you press a button and the AI comes up with a few possible paragraphs, of where your story could go next. GPT-3 wasn’t too great and its work required substantial editing, but it was already useful for sparking creativity and getting people past writer’s block. Commercial authors began using it to increase their productivity. Few talked about it publicly. You can read about a couple who did in this article from The Verge.

On Nov. 30, 2022, ChatGPT came out, built on top of GPT 3.5, and it was a giant step forward in usability and writing quality. It still take time and effort to get it to produce readable text. But once you get the prompts right, and put in examples of what you want to see, it can generate new text extremely quickly. It is missing a few functions — fact-checking, a calculator, Internet access, an easy way to to do custom training, and a training data set that is free of copyrighted content — but enterprise users are clamoring for those improvements, so expect to see major progress on those fronts in the near future.

The ChatGPT we have now is just the early preview version. As the technology improves, it will become transformative.

In particular, it will allow people who are bad writers, but who have great ideas for stories, to turn their visions into reality.

I personally think it’s a good thing. It will democratize the writing process, while improving the basic quality of everything out there.

For example, I love the Jack Reacher books. I’d love to get one a month — or even one a week. I don’t care that they’d all be very similar. I mean, I’ve watched 20 seasons of Law & Order. Twice. I’d be perfectly happy to throw money at Lee Child to get more books, and if he uses AI to help him speed up some of the more time-consuming parts of the writing process, while he focuses on idea generation and clever twists, so much the better, as far as I’m concerned.

But, at the same time, as a new fiction writer, I’m terrified. How am I going to compete with 50 books a year put out by Lee Child? People only have so much time to read. They’re not magically going to grow a second or third pair of eyeballs, just because there are more books out there.

Yes, there will continue to be people who make a living writing slow fiction. Just like there are people making money selling hand-stitched clothing and hand-carved wooden furniture and oil portraits painted with actual brushes on real canvas.

I could become one of those people, which would require that I significantly step up my marketing abilities. And, also, maybe I’ll have to resign myself to my writing remaining a hobby instead of turning into a full-time income.

Or I could embrace AI. Use it to become more productive, to level up my writing abilities, to improve my sales and marketing.

Or I could go somewhere in the middle. Use AI for some parts of the writing process, like transcribing my dictated notes, keeping track of character descriptions, helping me edit my stories for grammar, style, and clarity. And, of course, use AI for scheduling, marketing, social media outreach, generating blog posts and email newsletters and other promotional content.

It’s going to be a spectrum. I myself will probably be somewhere around the middle. I have a pretty weird, unusual writing style that is going to be hard for an AI to grasp. At least, in the next year or two. And I have an unusual setting and themes for my books, which makes it hard for AIs to keep track of the story. But the very fact that it’s unusual will, hopefully, make the books stand out.

But I know writers who are all in on AI. And I also know writers who aren’t going to touch it with a ten-foot pole.

I don’t think there’s any shame in either of these approaches. If it works for you, and if your readers are happy, then that’s what counts.

You might not think that AI-written books are real books. You might not think that music made with synthesizers in it is real music. Or that photography is real art. That’s okay — you don’t have consume those things if you don’t want to.

But there will be people who enjoy AI-written books, or AI-assisted books. Who don’t care how it’s produced as long as the story is good.

Whichever camp you’re in, just know this: The world has just changed. The genie is out of the bottle. Even if everybody bands together and decides to ban AIs altogether, the core technology is available, in open source form, for anyone to download and use. We’ve passed the point of no return. The cat is out of the bag. And all the other cliches. They’re all coming true.

GPT-3 was like the Apple Newton, or the Palm Pilot, or the Handspring Visor. Usable, for certain categories of applications. Specifically, GPT-3 was good for marketing copy.

ChatGPT is the first iPod.

The next iteration, the one with the fact-checking, and the ability to do math, and to learn from what you give it, that will be a revolutionary product on the scale of the smartphone.

For creative professions, it will help shrink that early-stage ramp-up period on the S-Curve.

But it won’t do away with the Dunning-Kruger Effect or the Gartner Hype Cycle. We’ll still have the peaks of inflated expectations, we’ll still have Mount Stupid, we’ll still have the Valley of Despair. We will expect too much from AI, and then be disappointed when it doesn’t deliver everything we want right away.

When we do eventually make it through to the end, the world will look very different than it does today.

MetaStellar editor and publisher Maria Korolov is a science fiction novelist, writing stories set in a future virtual world. And, during the day, she is an award-winning freelance technology journalist who covers artificial intelligence, cybersecurity and enterprise virtual reality. See her Amazon author page here and follow her on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn, and check out her latest videos on the Maria Korolov YouTube channel. Email her at [email protected]. She is also the editor and publisher of Hypergrid Business, one of the top global sites covering virtual reality.

I love these thoughts Maria! Awesome post