These violent undersea volcanoes harbor a secret: life

Off the coast of Italy, the Mediterranean’s most active volcano system is extremely volatile—yet our photographer found that marine life clings on all the same.

The night is so beautiful and so is the sea as our ship glides south along Italy’s coast. I’m at the helm of the Victoria IV and could easily follow my course observing the sophisticated instruments on the bridge. But how could I resist relying instead on the ancestral navigation guide known as the Lighthouse of the Mediterranean? The small glowing light on the distant horizon is not the work of humans but rather fiery lava explosions from Stromboli, a volcanic island in the Aeolian archipelago north of Sicily. Though this flickering glow is barely perceptible from afar, it has persisted for thousands of years, and we’re headed straight for it.

The Aeolian chain includes seven main islands and lies in the heart of the most active volcano system in the Mediterranean. Most of this activity occurs deep below the ocean floor. I’ve come here with Francesco Italiano, one of Italy’s preeminent volcanologists, and Roberto Rinaldi, a renowned Italian filmmaker, to document, in part, the hissing and spitting of hydrothermal vents that form on the flanks of undersea volcanoes and spew out curtains of bubbles made of mineral-rich hot gases. Volcanic activity in this region remains a threat to millions of people who live along Italy’s southern coastline, and Italiano and his colleagues want to find a way to better anticipate eruptions.

As a biologist, I want to see what kinds of marine species adapt and survive in places so hostile to life. It took two years to put together a research expedition, and we hope to unlock some secrets during our journey. The beauty of the world is important, but it is less fascinating than its mysteries.

We anchor first at Panarea, the smallest Aeolian island, and dive into shallow, acidic waters. Legend has it that ancient Romans moored here to clean barnacle shells off the hulls of their ships. Panarea is considered dormant, yet it hums with activity. Natural whirlpools give off a sulfur-like smell. Clouds of bubbles made of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide rise to the surface with a steadiness that makes it feel as if we are swimming through upside-down rain. Everywhere I look, I see the effect of this acidity on marine life, as the undersea landscape is barren of corals and hard-shelled organisms. A careless marine worm settled too close to the bubbles. Its calcareous tube is already dissolving. Elsewhere, the seagrass meadows of Posidonia, also known as Neptune grass, display whitened, burned leaves.

Only anaerobic bacteria, which do not need oxygen to survive, appear to flourish. On rocky walls, they form a thick felt covering that gently undulates under acidic caresses. We too feel the acid burning our faces, and when we resurface after a few hours in pungent surroundings, our lips and cheeks are chapped and the chrome taps on our diving suits have oxidized.

Off Panarea, scientists operate a monitoring station that tracks the bubble sounds for signs of volcanic activity increasing or tapering off. Italiano has linked an increase in bubble noise to a large eruption on Stromboli. But to prove his findings, he needs more evidence and wants our help exploring a unique site he discovered a decade ago during an expedition mapping the seabed. Sonar identified a narrow valley situated in a strangely perfect axis between Panarea and Stromboli, 12 miles away. The site is 300 feet long and 50 feet wide. Extending across it as far as the eye can see is a collection of thin, high chimneys of crystallized iron oxides that formed over thousands of years. Italiano named it the Valley of 200 Volcanoes.

We descend 250 feet. The landscape looks Martian red, orange, and yellow, though unlike the red planet, this forbidding place is alive, as if suffocating from excess activity. It exhales, it grumbles, it spits. Gas and hot water escape from the tops of the narrow chimneys, and while one chimney is being built, another seems to be dying out and a third is already collapsing. There is a great sense of precariousness here, but underwater life is like that—at once fragile and obstinate.

Hissing and spitting hydrothermal vents on the seabed release superheated gases that can reach nearly 300 degrees Fahrenheit. Yet life endures.

I watch a small flatworm slide incognito across the leaves of the pioneer algae that cover a chimney’s red slopes with a miniature forest, green with hope. The flatworm, smaller than my fingernail, is quite daring: It ventures to the top of the hydrothermal vents. It’s difficult to understand what interest it might have in walking on iron oxides in acidic water loaded with carbon dioxide.

Amid this same inhospitable environment a marine pantopod, or sea spider, appears. Its long legs converge toward a body so tiny it’s almost nonexistent. The only other place I have seen one this size is Antarctica.

To collect samples for Italiano, we insert a thermometer into the small vents at the top of the chimneys and take a vial of hot water and another of gas. We have time to sample only 20 before we have to resurface. We’ve been on the bottom for an hour and must spend three more on the way up to allow us and our samples time to decompress.

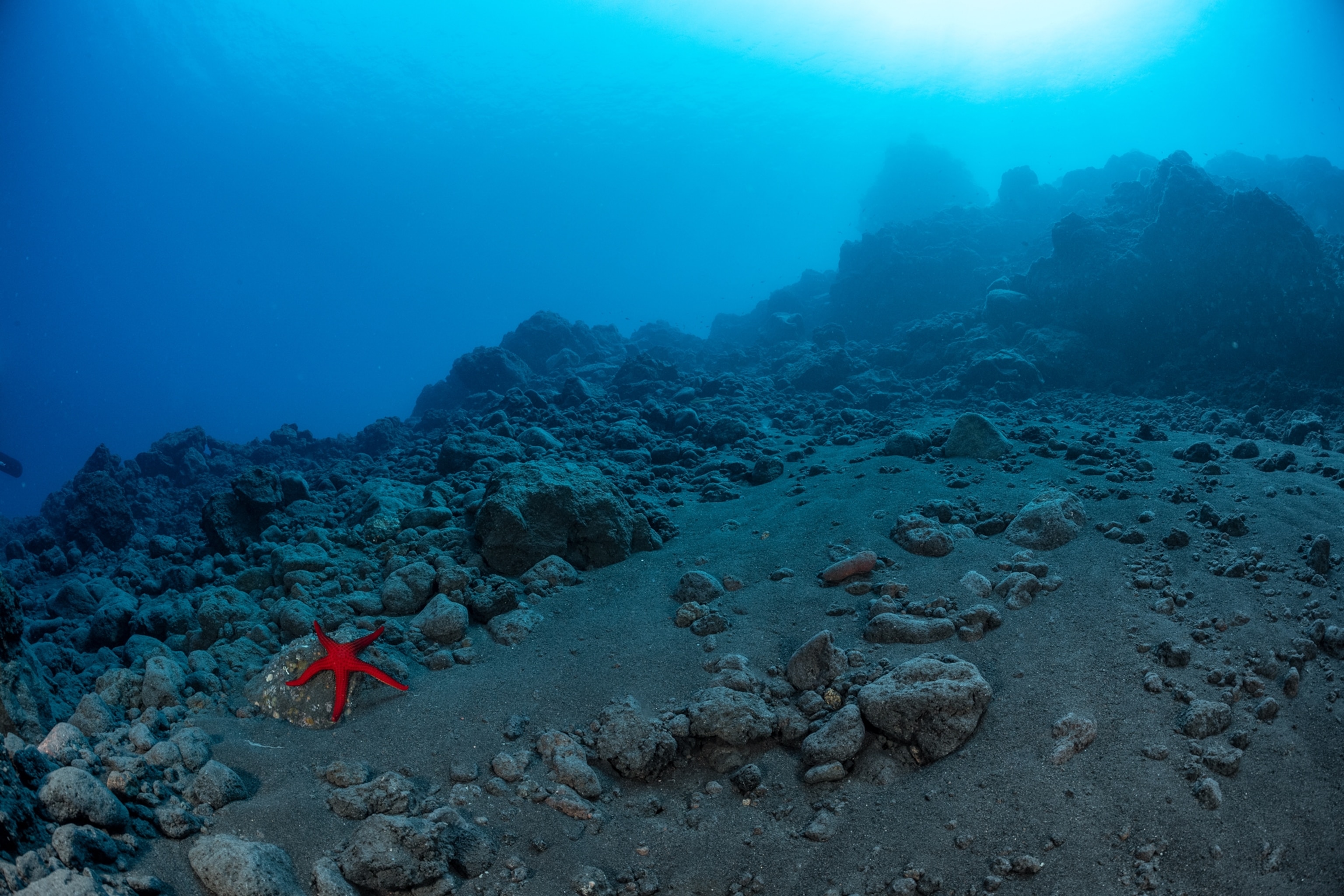

Finally, aboard the Victoria IV, we head to Stromboli, whose smoking summit can be seen in the distance. Frequent tremors have caused the peak to slough off soil, rock, and sand, destroying everything in its path. One side of Stromboli is green with olive and fig trees; the other is a blackened corridor through which lava flows and the rocky debris slides into the sea. The seabed is constantly redesigned after successive disasters, and I’m curious to see how the ecosystem below has recovered after the last major landslide, in 2002.

There is a great sense of precariousness here, but underwater life is like that—at once fragile and obstinate.

As we descend, fields of Cystoseira, bushes of yellow-hued algae brimming with hidden marine animal life, disappear abruptly into black sand and jagged stones. One might think we were on a barren planet if an anglerfish hadn’t appeared in the black silica dust raised by our fins. On closer inspection, we spot a series of pioneering species that have begun their work of reclaiming the area. Nearby, a field of white gorgonian corals survived a close call: It is half-buried in black sand of a recent flow but still alive. Then a juvenile dogfish, about eight inches long, cruises by. This baby shark, whose fate is uncertain, is a perfect symbol of a reborn ecosystem.

Successive landslides have also miraculously spared a magnificent pinnacle of volcanic rock, an upright needle towering 130 feet. Rinaldi found it 30 years ago, and when we locate it along the rearranged seafloor, we find it hosting flourishing underwater life precisely because it has been spared. It’s common to talk about the fragility of nature, yet nature clings on, resists, and bides its time.

After three weeks at the foot of volcanoes, we made our last dives in the Bay of Naples, about a mile offshore from Italy’s third largest city, where Rinaldi wanted to explore a hole in the bottom of the sea. Researchers know nothing about it, but the hole is the stuff of legend among local fishermen. It’s said a mysterious “mouth” exists at the bottom of the bay, which swallows their nets, lines, and traps, never to be seen again. To say this dive is attractive would be an outright lie. The water is green, murky, and cold—and the muddy seabed is littered with trash. There is nothing to see, but there is a sense of curiosity to be satisfied. Can it really be that on this seabed, soft and flat for miles around, lies the entrance to a vertical, rocky cave so mysterious that no instrument has ever probed its depths?

As we descend, suddenly we reach the edge of the opening. The soft mud gives way to black rock. My depth gauge shows we are 165 feet down when we tip into the black hole. The water is too murky to see the whole perimeter, but one can imagine a large well measuring probably more than 30 feet in diameter. At 250 feet, the cylinder opens up into an abyss so large that the beam of our lamps cannot locate a wall. At 310 feet, we touch bottom. Looking up, we can still make out a small green glow at the shaft entrance, so far away that it looks like a small mousehole. We find the chamber’s walls and discover an ecosystem has established itself here. The walls of black rock are covered with small filter-feeding invertebrates and crossed by rare long-clawed crustaceans. Among the creatures living on borrowed time, we identify a rare species: a carnivorous sponge.

A sonar image solves the mystery of where we are: in the center of a huge circular chamber, as if we are in a gigantic wine carafe with a long, narrow neck suddenly widening into a large basin. It is probably an ancient magma chamber emptied of its lava. Sooner or later it will collapse inward, generating a small tsunami that will gently lap against Naples’s beaches. We have brought equipment for scientists and install it on the chamber’s floor to measure water circulation, temperature, acidity, and secrets of the deep.

We ascend with a strange sensation. Our journey began in a familiar world—with the sky, the surface of the sea, the sea, and the seabed. We did not dive to the bottom of the sea, but rather under the bottom of the sea. And there is life.

This story appears in the June 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

Environment

- This floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

History & Culture

- These were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ eraThese were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ era

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar