By Doug Mahoney

Doug Mahoney is a writer covering home-improvement topics, outdoor power equipment, bug repellents, and (yes) bidets.

The more you carry around a pocket knife, the more uses you’ll find for it. Everything from opening delivery boxes to fishing little objects out from between floorboards can be accomplished without having to search around for a specific tool.

After researching pocket knives for over 60 hours and talking to two people who have reviewed at least 450 knives between them, we tested nearly 30 knives—by slicing up 20 cardboard boxes and peeling 30 apples—and found that the Columbia River Knife and Tool Drifter is the best knife for most people to carry every day.

Everything we recommend

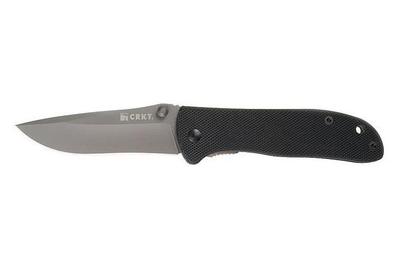

Our pick

The Drifter offers a compact size and a butter-smooth blade deployment. The grip area works with all hand sizes and remains comfortable even during tough cutting.

Buying Options

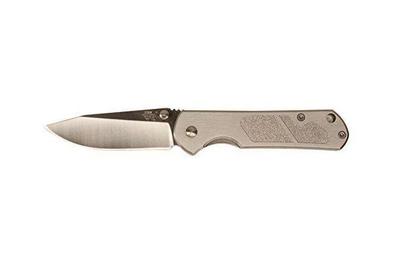

Runner-up

The robust metal build of the Zancudo, combined with the excellent ergonomics, makes this the knife of choice for tougher work.

Buying Options

Budget pick

The 710 has many of the same high-quality touches as our main pick, but the all-metal body can be slippery. Often available for around $20, it’s a steal.

Buying Options

Upgrade pick

The Mini Griptilian has a steep price tag, but it’s better than the others by nearly every measure. The distinctive blade-locking system and movable pocket clip make this knife fully ambidextrous.

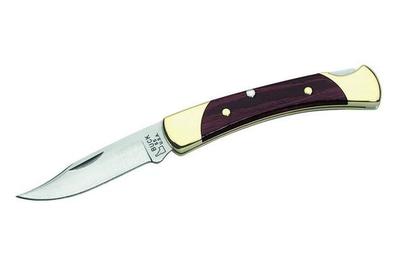

Also great

The 55 has none of the modern convenience features of the other knives we tried, but it does have a timeless feel, a comfortable handle, and a durable build quality.

Buying Options

Our pick

The Drifter offers a compact size and a butter-smooth blade deployment. The grip area works with all hand sizes and remains comfortable even during tough cutting.

Buying Options

The CRKT Drifter shares the two basic characteristics of most of the knives we tested: The blade is about 3 inches long, and you can open and close it with one hand. On paper, the Drifter offers nothing unique, but it excels at all of the small elements that make for a successful knife. The most impressive of these is the smoothness of the blade’s pivoting action, which is among the nicest we tested and on a par with that of knives costing four times as much. The Drifter’s handle is contoured to fit both big and small hands, and it has a light texturing that improves the grip. This model has excellent fit and finish, and it doesn’t have a cheap plastic feel like many of the knives in its price range—usually costing around $30, it’s a bargain.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENTRunner-up

The robust metal build of the Zancudo, combined with the excellent ergonomics, makes this the knife of choice for tougher work.

Buying Options

If the Drifter isn’t available or if you’re looking for a real workhorse of a knife, we also like the Blue Ridge Knives ESEE Zancudo.1 Compared with the Drifter, the Zancudo has a larger handle, a stronger blade lock, and a lot more metal in the body. Those features, as well as the unusual and comfortable teardrop-shaped handle, make this model a great knife for tougher work and more aggressive cutting. We think that this added durability and performance are unnecessary for standard everyday use, and that the Drifter, with its adequate strength, lighter weight, and smaller footprint, is the better option for most. Still, in our tests the Zancudo was our choice for tougher jobs, such as when we headed into a DIY project.

Budget pick

The 710 has many of the same high-quality touches as our main pick, but the all-metal body can be slippery. Often available for around $20, it’s a steal.

Buying Options

If you’re new to knives and want to make the smallest investment possible to see if you like carrying one, we like the Sanrenmu 710 (aka 7010). It’s similar in a lot of ways to our main pick—it has roughly the same size and the blade pivot is almost as smooth. But the all-metal handle is less comfortable and can become slippery in damp or sweaty hands; we noticed this problem when holding the knife and when flipping the blade out. The good news is that the 710 is typically sold for around $20. This pricing is impressive seeing as the overall quality in our tests was better than that of many of the $30 to $50 knives we tried.

Upgrade pick

The Mini Griptilian has a steep price tag, but it’s better than the others by nearly every measure. The distinctive blade-locking system and movable pocket clip make this knife fully ambidextrous.

If you have a larger budget and want a knife that nails all of the little details, we recommend the Benchmade Mini Griptilian. Compared with our other picks, it’s simply a better knife—better pivot, better blade steel, better ergonomics, and better locking system. Because of the lock and the reversible pocket clip, this model is a fully ambidextrous knife. We believe that most people will be more than satisfied with the CRKT Drifter, but if you take good care of your knives and want one with premium touches, the Mini Griptilian is a great investment.

Also great

The 55 has none of the modern convenience features of the other knives we tried, but it does have a timeless feel, a comfortable handle, and a durable build quality.

Buying Options

We also tested two traditional knives, and if you prefer a more classic look and style, we recommend the Buck Knives 55. Its design has an unquestionably age-old feel, but that comes at the expense of more modern touches such as a pocket clip, a one-handed open and close, and a textured handle. Still, the Buck Knives 55 has a very sturdy body and nice overall construction, which is evident in how the lock snaps open and closed. To us, the biggest drawback is that you need two hands to open and close this blade, but if you’re okay with that, this Buck model is a fine choice.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENTWhy you should trust us

To learn more about pocket knives, we turned to two prominent blade reviewers, conversing with both via email. Dan Jackson of BladeReviews.com has been running his site and reviewing knives since 2010. In that time, he has reviewed “a couple hundred” knives ranging in price from a few dollars all the way to $800. We also corresponded with Tony Sculimbrene of Everyday Commentary, who has been reviewing blades since 2011; he told us he has personally reviewed “probably more than 250 knives” and handled at least a thousand. He also writes about knives and other EDC gear for AllOutdoor.com, GearJunkie, and Everyday Carry. To round out our knowledge, we also spent hours combing through knife-enthusiast forums such as BladeForums.com, knife retailer websites, and YouTube knife reviews.

I’ve also been a daily knife carrier for nearly 25 years. I spent 10 of those years in the construction industry, in work that entailed heavy daily knife usage. My knife experience also extends into woodcarving, which I do as a hobby.

Who this is for

At its most basic, an everyday carry (EDC) knife is a practical tool that helps you tackle small, routine problems. To fit comfortably in a pocket, it should be a relatively compact knife. It won’t bushwhack a trail, but it will spare you countless trips to the kitchen drawer to get something to break down the recycling or open a package. While you can easily spend over $100 on a quality knife, and it can be well worth that price, for this guide we focused mostly on entry-level knives that you can get for less than $50, so that you can try out the utility of an EDC knife without breaking the bank.

Blade reviewer Tony Sculimbrene told us that a good EDC knife “should be able to do general utility tasks, like package and box opening, and, if you go outdoors, outdoor/camp tasks like food prep and light whittling/carving.” While these are the foundational reasons to carry a knife, their usefulness is far more universal. In a three-week span, I’ve used pocket knives to sharpen pencils, retrieve Legos from between floorboards, cut twine, remove an event wristband, open a bag of chicken feed, trim the odd thread hanging from a shirt, and remove ticks and splinters when no tweezers are available.

But EDC knives are not for everyone, and you have certain considerations to take into account if you’re looking to carry one. First, even though EDC knives are typically small, they’re still dangerous, so you need to handle them responsibly. Second, you need to maintain them, which means sharpening them.

You also have legal considerations. Knife laws vary from state to state and often from city to city. Some areas, such as New York City, have extremely prohibitive knife laws. We found the American Knife & Tool Institute, a knife-advocacy group, to be the most reliable source of information on this topic, but we also recommend checking in with local law enforcement to get the most up-to-date information.

But if you’re really after functionality in your pocket knife, we recommend a multi-tool, which we cover in much more detail here.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENTHow we picked

Choosing a knife is a personal decision, and 10 different people are likely to have 10 different favorites. But after speaking to experts and drawing from our own experience, we decided to focus on knives with the following common features and attributes.

Folding blades (as opposed to fixed blades): Most folding knives (known as folders) are small enough to fit in a pocket and have a general nonthreatening sense of utility about them. In social situations they’re likely to be more acceptable than a fixed-blade knife on a belt sheath. Fixed blades do have their place, particularly among outdoor enthusiasts, but we believe they aren’t the best option for a simple, discreet EDC blade.

Roughly a 3-inch blade length: Blade reviewer Dan Jackson called a 3-inch blade the “sweet spot” for size and explained to us that a 3-inch blade is “a functional size and provides plenty of cutting edge and plenty of handle to hang on to.” Tony Sculimbrene, writing at his site, says he doesn’t see the point of going larger than 3 inches for an EDC blade. In a number of reviews on his blog, he refers to “3:4:7” as the “golden ratio” of a folding knife—a 3-inch blade, a 4-inch handle, and a total length of 7 inches. In one review Sculimbrene refers to a length of 2½ to 3 inches as being his “[ideal] size for an EDC knife.”

Bigger blades have a few drawbacks. Sculimbrene told us, “A knife has to be VERY well designed to be 3.5 inches and not feel unnecessarily bulky or clumsy in the hand.” Jackson also acknowledged the awkward optics of a larger blade, saying that a knife shorter than about 3¼ inches “won’t be misinterpreted as a weapon.”2

Lightweight: A consideration somewhat similar to blade length, weight is an important factor for anything you carry with you all day. We focused on knives that wouldn’t significantly weigh down most pockets, but didn’t sacrifice build quality or utility.

A drop-point blade shape: For blade shape, we focused our search on the classic drop-point style. With this design, the top edge of the blade arcs slightly downward toward the tip. The edge of the blade has a curve at the tip and then straightens out as it heads back to the handle, similar to what you can find on many chef’s knives. According to Jackson, this design is “a well-rounded blade shape” that offers “a good cutting edge, some belly (the curve to the edge towards the tip), which is good for slicing into things, and a fine tip for detail work." He also noted that the drop point is not a threatening shape. “A clip point blade is very practical for the same reasons, but it can look more aggressive, especially in a larger knife.” Drop-point shapes are easier to maintain, too. Sculimbrene told us, “One issue that a lot of people don't think about is the more complex the blade shape is, such as with a recurve or a tanto, the more difficult it is to sharpen and maintain.”

One-handed opening: Seeking the convenience of a one-handed open, we focused on knives with thumb studs, thumb holes, or flippers. Thumb studs and thumb holes provide a grip on the blade so that your thumb can flip it open. A flipper is a small tab that sticks out the back end of the handle; when you give it a quick flick, the blade pops open and locks. Jackson told us, "I like thumb studs, flippers, and thumb holes for deployment methods. Done properly, these allow for easy one-hand opening."

Liner locks, for one-handed closing: This style of lock secures the blade in the open position and offers easy closing with one hand. When you open the blade, a strip of the metal handle lining springs to the center of the knife and engages with the back end of the blade, locking it in place. To unlock the blade, you use your thumb to move the lock to the side while simultaneously shifting the blade forward with your forefinger. It’s an easy maneuver to master. It’s also doable with either the left or right hand, although easier with the right. Sculimbrene told us, “In terms of locking systems, the liner lock … is probably my favorite.”

Frame locks are essentially the same thing, except they’re a thicker piece of metal that engages with the blade. Experts consider frame locks to be the stronger design of the two, but both are plenty durable for everyday use.3 As Jackson told us, liner locks “work great for daily utility tasks, but don't try to chop down a tree with them." In a review, Sculimbrene writes, “[In] the role of an EDC knife I think a liner lock is more than strong enough.”

A pocket clip: Most inexpensive knives have a single-position pocket clip, but more expensive models often give the option to move the clip to either side of the handle, as well as to either end. This is a nice feature to have, but it’s not an essential one, particularly if you’re new to knives and haven’t yet developed a preference. Sculimbrene told us, "A good pocket clip is a huge plus for a knife. I don't think it is required, but a good one is a treat. If you have a good handle design four position clips aren't necessary.”

Acceptable blade steel: Blade steel determines a blade’s strength, its corrosion resistance, and how often you’ll be sharpening it. Cheaper steels are softer and prone to dulling quicker, but are easier to sharpen than more expensive steels. We found that, depending on the steel, knives fell into a series of price ranges. For instance, the majority of knives from reputable manufacturers in the $15 to $50 range, where we spent most of our time, are made of either 8Cr13MoV or AUS-8, both of which are considered decent, but not great, steels. As Benjamin Schwartz writes in a review Jackson’s site, “For me, 8Cr13MoV is the baseline for modern steel, setting the bar for acceptability in every area, but impressing in none other than sharpenability. I’ve never been surprised by 8Cr13MoV, but never really disappointed by it either.”

A good value for the price: To find an entry-level knife with features that would satisfy an enthusiast, we centered our research on the $15 to $50 range. Sculimbrene made the interesting point that “if you are talking under $40, the quality is pretty much the same from $40 down to about $5 if you know what to avoid.” We found this to be true—we saw a lot of terrible $30 knives, and at least one really good one for considerably less (like our budget pick). We also looked at knives in the $50 to $100 range, where “you get a huge uptick in quality,” according to Sculimbrene. He explained, “At around $50 you can find a wide variety of knives with superior steel, handle materials, and fit and finish.” Jackson told us he didn’t “think that anyone ‘needs’ a $75 pocket knife” but recommended “venturing into this price if you enjoy knives and want a more premium product.” But ultimately, he said, “a $25 knife will open a box like a $100 knife will.”

No serrations: The primary advantage to serrations is that they offer an increased ability to cut rope. On the downside, they’re difficult to sharpen, and they don’t make as clean of a cut. Sculimbrene, at his site, writes, “I do not like serrations. I don't do enough rope cutting tasks to make the serrations worth the sharpening hassle they cause.” Jackson agreed: “If you maintain your plain edge knife you will never miss having serrations.”

No assisted open: Knives with assisted open have an internal mechanism that springs the blade to the open position once it is just barely out of the handle.4 Sculimbrene has strong opinions on such knives, writing at his site, "I do not like assisted opening or automatic knives. If a manual knife is well designed (like a flipper or a thumb hole) it will open just as fast. As such, the assisted opening or auto just adds parts that can break with no accompanying benefit. If you have an application that needs fast and thoughtless deployment, like combat or rescue, assisted and auto knives have their place. Otherwise, they aren't worth it."

A reliable model: We kept our search to established, time-tested models. Many knife manufacturers crank out new designs on a seasonal basis, so their catalogs are constantly shifting around. Sculimbrene explained that “knife companies generally ‘retire’ about 10% or 1/3 of their knife designs a year and sort of use the knife enthusiasts as product testers, moving successful designs in their evergreen line up.”

Sticking closely to the criteria above, we selected almost 30 knives to call in for a firsthand look. Our list focused mostly on reputable manufacturers such as Benchmade, CRKT, Gerber, Kershaw, and Spyderco. We also included a few outliers: The Spyderco Delica 4 and Dragonfly 2 have the lockback system but are regarded in the knife world as two of the best models available. In addition, we looked at two traditional folders with lockbacks; these models, from Buck Knives and from Case, rely on a fingernail nick. Last, a few knives with clip-point blades made their way into our testing, mostly since their high popularity and strong reputation made them hard to ignore in a comprehensive evaluation of the category. For this review, we did not look at any multitools like those from Leatherman and Gerber (we have a separate guide for those).

How we tested

Once we had the knives in hand, it didn’t take long for us to narrow things down to about 10 models based on fit and finish alone. We quickly dismissed knives with impossible openings or awkward ergonomics. After that, we simply spent the majority of our testing carrying the knives around and using them daily. This approach gave us the best feel for the overall combination of ergonomics, pivot design, and handling, something that no lab testing could truly zero in on.

We also used these blades to slice up about 20 cardboard boxes and peel about 30 apples. These two tasks, one aggressive, the other delicate, gave us a sense of how comfortable the handles were and how easy it was to maneuver each blade for different types of cutting.

During testing, we sharpened our blades with the Spyderco Tri-Angle Sharpmaker, a highly regarded sharpener among knife enthusiasts. In a review, Jackson writes, “I cannot recommend the Sharpmaker more highly. It’s a versatile no-nonsense sharpening system that almost anyone can learn how to use.” Touching up a blade on a whetstone takes skill and practice, but you can find easy-to-use systems like this (or the similar, cheaper Lansky 4 Rod Turn Box) that can bring dull blades back to razor sharpness in minutes.5

Also great

The compact and easy-to-use Tri-Angle Sharpmaker can bring a dull knife back to life in a matter of minutes.

Buying Options

We didn’t do any specific tests on edge retention. It is well documented that the better steels found on more expensive knives hold an edge longer than their less-expensive counterparts. We didn’t feel the need to rehash this information. But beyond that, we also believe that while edge retention plays a role in a knife’s quality, it doesn’t play a critically important one. As Benjamin Schwartz writes in one review, “I think that, in our spec-obsessed modern age, we forget that poor edge retention in any modern steel is [still] pretty decent: I cut through a lot of cardboard with the [very inexpensive] 710, more than I could reasonably expect to deal with in a month of standard use, before I noticed any real performance issues. I still prefer better steels, don’t get me wrong: I just think that we tend to hyperventilate when it comes to comparisons that, in 90% of the situations we find ourselves using blades in, don’t matter.”

Many of the knives we tested have at least 8Cr13MoV steel, which is the specific steel that Schwartz talks about in that review. In the end, even the so-so steels will be fine for day-to-day use. If you’re rough on your knives, you’ll need to sharpen them more often, but if you’re just cutting packing tape, trimming butcher’s string, and opening the mail, you should be able to go quite a while between sharpenings.

Through our testing, we found that the major differentiators between the knives were the handle ergonomics, the ease of unlocking, and the smoothness of the blade pivot. All of the knives we tested could open, close, lock, and cut—but not all of them could do those things equally well. In fact, we were surprised at the quality differences between similarly priced models that looked identical on paper. As Sculimbrene told us, there are some really good cheap knives, but we could determine which were which only after handling them. At a certain point, the stats fail and only hands-on experience works.

After handling so many knives, we developed a number of preferences. We preferred thumb studs and thumb holes over flipper mechanisms like those on the popular Kershaw knives we tested. Flippers can open only one way: extremely fast. Thumb studs offer a slower option, as well as a quick flip. During testing, I attended a number of family gatherings, where we used the knives for cutting rope for a kid’s swing, shaving off an aggressive splinter on a dock, and opening a few boxes. Some people have a strong reaction to a blade deploying at lightning speed, accompanied by the distinctive swooshing click of the blade lock engaging, so you’ll certainly have situations where a slower blade deployment is more appropriate.

We also found that knives with all-metal bodies can get slippery. We much preferred the sure-handed grip of carbon fiber or G10 (a fiberglass laminate).

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENTOur pick: CRKT Drifter

Our pick

The Drifter offers a compact size and a butter-smooth blade deployment. The grip area works with all hand sizes and remains comfortable even during tough cutting.

Buying Options

After all of our research, conversations, slicing, dicing, apple peeling, and cardboard cutting, we believe that the best knife for most people is the Columbia River Knife and Tool (CRKT) Drifter. Of all the knives in our test group, the Drifter offers the best overall proportions: It has a blade long enough for common tasks, a handle that can fit all sizes of hands, and a folded length that doesn’t take up too much space in a pocket. The fit and finish on the knife is excellent, and the blade opens with a smoothness common to more expensive knives. Once open, the blade locks with a liner lock that is secure yet simple to disengage. The G10 fiberglass laminate handle offers a light grippiness, and all of the edges are nicely machined and rounded over, which wasn’t the case with many of the other knives we tried.

The Drifter has a 2⅞-inch blade, a folded length of 3⅝ inches, and a total length of 6½ inches. The blade is long enough to slice up an apple or cut a sandwich in half. In our tests, we also liked that the underside was long enough to accommodate a sawing action if necessary, such as when we were cutting twine from hay bales; it was harder to do the same with shorter blades.

Although the Drifter’s handle is small, it’s comfortable in both big and small hands. Small and medium hands will be able to get a full four-fingered grip on the handle, while larger hands will get only three. But even with the three-fingered grip, the contoured back end of the handle tucks right into the base of the thumb and remains comfortable. In our tests, knives with even slightly larger blades—anything over 3 inches—had handles that started getting big for smaller hands.

The Drifter’s small size also meant we could easily shift the knife around in the hand. The shape of the grip naturally placed our fingers for good control over the blade, such as when we sharpened pencils or skinned apples. The back of the blade, at the handle end, has some grooves (called jimping), which gives the thumb a little traction during tougher cuts.

With the knife folded, it’s a good size for a pocket—big enough to find easily yet small enough that it can share the space with a set of keys, a wallet, or a small flashlight.

We found that the smoothness of the Drifter’s thumb-stud deployment was better than that of any other knife in the under-$45 price range and on a par with that of knives costing three or four times as much. While opening, the blade offers a smooth, even resistance, and once the liner lock is engaged, it holds firm with no blade movement at all, either back and forth or side to side. With a little practice, you can easily pop the blade open by flicking your thumb like you’re flipping a coin.

The handle is made of G10, a durable fiberglass composite, and CRKT has given it a very light texture. Even with damp or sweaty hands, it’s easy to hold and grip. Unlike knives with all-metal handles, the Drifter never felt slippery to us.

We found that it was those smaller touches, such as the feel of the handle and the ease of the blade deployment, that made the Drifter such a winner. Other knives with the same overall dimensions weren’t anywhere as nice as the Drifter. For example, the Gerber Mini Swagger, on paper, is the same as the Drifter, but the thumb stud is difficult to use, the lock is way too stiff, and it’s not as comfortable in the hand.

The blade of the Drifter is made of 8Cr14MoV steel. In a review of the knife, Dan Jackson writes, “I like it because it’s easy to sharpen, holds an edge reasonably well and has decent corrosion resistance.” The Drifter’s steel is very similar to 8Cr13MoV, a standard midgrade blade steel found on the majority of brand-name knives priced under $45. During testing we had no issue with it at all, and we liked how easily we could get a shaving-sharp edge. All knives need maintenance, and while the Drifter may require a tune-up more often than a $80 knife, it still offers a solid amount of performance. After we used it for small daily tasks over the course of two weeks, the Drifter’s blade was still able to make a clean slice through a sheet of newsprint.

The praise that the knife community has heaped on the Drifter is unanimous. Across all the professional reviews of the Drifter, we couldn’t find a bad one. Among many knife aficionados, the Drifter consistently pops up in conversations about the best inexpensive EDC knife. Jackson and Sculimbrene include the Drifter on their respective best-of lists and have given the knife fantastic individual reviews.

On his best-of list, Sculimbrene names the Drifter the “Best Budget Folder” and writes, “This is my favorite CRKT and one of the best knives out there under $30.”

Jackson writes in his review that the Drifter is “both well made and inexpensive” and that it offers “[e]verything you would expect from a much more expensive knife.” He also makes the point that it’s a “great ambassador for the knife world.”

The Drifter is a bargain, and during our use it felt more like the $80 to $100 knives we tested. It far surpasses many of the others in its price range, which commonly have cheap materials, too-tight pivots, or locks that are hard to disengage.

Flaws but not dealbreakers

For all of the positives of the Drifter, we wish it were better in two areas: the single-position pocket clip and the slight recurve of the blade shape. Both of these shortcomings are well-documented in other reviews, as well.

The Drifter’s single-position pocket clip is set in the right-handed, tip-down configuration; you get no other options. Some of the other nice knives we found in this price range, such as the Zancudo (our runner-up), the Kershaw Chill, and the Ontario RAT II, all have multi-position pocket clips that either cater more easily to left-handed users or at least offer the right-handed tip-up position. It’s unfortunate that the Drifter doesn’t provide such customization, but we don’t think that’s an essential feature. In his review Sculimbrene calls out the lack of positioning options but still refers to it as “a very good clip for the money.”

The other ding against the Drifter is the slight recurve of the blade edge as it heads back toward the handle. Recurves are designed so that they can “grab” better, particularly with a sawing cut, but the downside is that they’re harder to maintain. The unfortunate thing here is that the Drifter’s curve is enough to make sharpening a little more difficult but not enough to really aid in cutting. The sharpening system we used for testing, the Spyderco Tri-Angle Sharpmaker, is designed to deal with recurves, so we didn’t have a problem, but if you’re sharpening on a traditional stone, it will be a little trickier.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENTRunner-up: Blue Ridge ESEE Zancudo

Runner-up

The robust metal build of the Zancudo, combined with the excellent ergonomics, makes this the knife of choice for tougher work.

Buying Options

If the Drifter is not available or if you tend to take on more aggressive tasks with your knife, we recommend the Blue Ridge Knives ESEE Zancudo. With a full 4-inch handle, it’s a little larger than the Drifter, so it’s ideal for medium to large hands (although still workable for smaller ones). The Zancudo has a nice, smooth pivot and a frame lock that’s stronger than the Drifter’s liner lock. The teardrop handle shape is a little unusual, but in our tests it was among the most comfortable to hold, especially when we were really bearing down on it. Due to the amount of metal in the body of the Zancudo, it’s heavier than the Drifter, but that metal also gives the knife a sturdier feel. We’re convinced that the more-compact Drifter is the better option for most people, but if you beat on your knives, the Zancudo is a great choice. As blade reviewer Dan Jackson writes, “the Zancudo isn’t a particularly sexy knife, but it is practical, robust, and well made.”

The handle of the Zancudo looks a little odd, but it fit our hands perfectly. We found it comfortable during aggressive cutting and easy to shift around for more delicate tasks. In their respective reviews, both Dan Jackson and Tony Sculimbrene call out the Zancudo for its unusual aesthetics but overall success. Jackson writes, “While on paper the handle of the Zancudo looks a little goofy, in hand it all makes sense.”

The construction of the handle is also unusual, with each side sporting a completely different look: The clip side is entirely metal, while the other side is scaled with a lightly textured fiberglass-reinforced nylon. We liked this design because the smooth metal side reduced friction while we moved the knife in and out of a pocket, but at the same time, the nylon side offered more than enough grip for a secure hold. In addition, the body of the Zancudo is very thin (thinner than the Drifter). Jackson writes that he “found it very pocketable.”

The pivot is also nice, although not as smooth as the Drifter’s. The Zancudo opens with a good, grippy thumb stud, and with a little practice, you can flick open the blade without any issue. It’s a frame-lock knife, so it requires more finger strength to disengage the lock, but we never thought that created a problem.

The Zancudo has a two-position pocket clip, both right-handed but with a tip-up option and a tip-down option (or you can remove it altogether).

The Zancudo’s blade steel is AUS-8, another of the solid midrange steels. Jackson writes that AUS-8 “offers a good balance of toughness, edge sharpness and corrosion resistance.” Experts consider AUS-8 as being on a par with, if not a whisker better quality than, 8Cr13MoV steel. We see no practical difference between this steel and the Drifter’s 8Cr14MoV.

Like the Drifter, the Zancudo gets high marks from knife reviewers, including both of the experts we interviewed. Jackson told us that he was especially fond of it and that it’s “one of his favorites” in the sub-$40 price range: “I still use and enjoy my Zancudo several years after purchasing it.” Sculimbrene, in his review, writes that he isn’t a fan of the sizable pocket clip or the aesthetics of the handle. But he goes on to say, “I LOVE the Zancudo blade shape. It is simply sublime. Simplicity in a Shaker sense--pure, unadulterated functionality.” He also writes, “It has a few drawbacks, but man is the blade shape awesome.”

Overall, the Zancudo offers a great feeling of utility, and as our testing wore on, it really won us over. We believe that the Drifter, due to its smaller size and smoother operation, is the better pick for most people, but in our tests, when we knew we would be working a knife extra hard, like heading into a house project, we preferred having the Zancudo with us. Sculimbrene also picks up on this general sense of durability in his review, writing, “Go buy this knife. Go thump on it. You'll be surprised how much it can do. It will be the knife you reach for when you don't want to mess up that $1000 custom.” Jackson, in a similar fashion, writes that the Zancudo is “sure and comfortable, and the knife is ready for work.” He told us that the Zancudo “will provide years of service with proper care and maintenance.”

We tested the black-handle Zancudo with the stonewashed blade, but the knife is also available with a brown, tan, or green handle and a black blade.

Budget pick: Sanrenmu 710 (7010)

Budget pick

The 710 has many of the same high-quality touches as our main pick, but the all-metal body can be slippery. Often available for around $20, it’s a steal.

Buying Options

If you’re new to knives and want to spend as little as possible but still get something decent, we recommend the Sanrenmu 710 (aka 7010). Usually priced around $20, this model was the least expensive knife we tested—and also one of our favorites. In spite of the knife’s low cost, the pivot and thumb-stud flipping action have a smoothness similar to that of the Drifter. The overall size is almost identical as well, consisting of a 2¾-inch blade, a 3¾-inch handle, and a total length of 6½ inches.6 The drawbacks: The all-metal body can get slippery, and we found the company to be very unresponsive to our queries, which raised some red flags about customer service and warranty support.

Like the Drifter and the Zancudo, the 710 has a thumb stud, so you can deploy the blade slowly or, with the flick of your thumb, quickly. In our tests the pivot had an even resistance, better than that of some of the $30 knives we tried. The blade locks in place with a nice, flexible frame lock that you can easily move out of the way to close the blade.

The 710’s blade is made of 8Cr13MoV, which is what we found on a lot of sub-$45 knives. In a guide to blade steels, reviewer Dan Jackson writes that it is “actually excellent steel for the money.” Jackson continues: “Like AUS-8, it lacks the edge retention of the higher end steels but can take a wicked edge and is reasonably tough and corrosion resistant. For EDC knives in the $35 and under bracket 8Cr13MoV is really tough steel to beat.” Discussing the 710's blade steel at Jackson's BladeReviews.com, Benjamin Schwartz writes, “Yes, 154CM or N690Co or S30V are better steels by a long shot, but in a regular week of use I certainly wouldn’t appreciate the difference.” As with the Drifter, we believe that the bottom line is that all knives need maintenance, and given the low cost of the 710, it’s unreasonable to expect this knife to have a high-end steel. In fact, if you’re unfamiliar with knife sharpening, 8Cr13MoV is a great steel to learn on, because restoring an edge is so easy.

In Schwartz’s review of the knife, he also writes, “Sanrenmu helped to establish the budget knife archetype, and here we have as distilled a representation of that archetype as possible. The 710 is a very, very good knife.”

But the Sanrenmu 710 has a number of drawbacks.

Functionally, the all-metal body tended to be slippery in our tests, especially when we tried to get purchase on the thumb stud. If your hands are damp or oily, forget about it. The knife handle also seemed to twist slightly while we were gripping it, something that didn’t happen with the Drifter. The handle has a light amount of texturing, but as Schwartz writes in his review, “it doesn’t help with the grip during deployment, which this knife could use.”

The 710 also has only one pocket-clip position (right-hand, tip-down). It would be nice if this model offered more options, but again, we didn’t see many under-$45 knives with multiple clip options, and we don’t think it’s a critically important feature. For a knife typically priced around $20, that’s an expected sacrifice.

We’re also not impressed with Sanrenmu’s customer service, so we question the company’s stated warranty. The box of the 710 says that Sanrenmu will replace any knife with a quality defect, but we’re skeptical. We sent numerous emails to the company while researching this article and never got any response. Blade reviewer Tony Sculimbrene also raised the point that with Sanrenmu, as with other Chinese manufacturers, “we don’t know who they are.”

The last drawback is that Sanrenmu is a topic of controversy among knife aficionados, and the 710 is a perfect example of why. The body design of the 710 bears a significant resemblance to that of the highly regarded Chris Reeve Sebenza, which retails for $350 to $500 depending on the features and blade steel. Sanrenmu isn’t trying to pass its knife off as a Sebenza, so the company is not counterfeiting (which is a huge problem in the knife world), but the similarities are difficult to deny. Jackson told us he didn’t see a huge problem with the 710: “[It’s] nothing like the real [Sebenza]. It does share a similar profile, and both knives have frame locks, but that’s about it in my opinion.” He told us that “no one would confuse the two” and distinguished this situation from those where “there are people making counterfeit clones that are designed to look like a real Chris Reeve knife.” Sculimbrene expressed a different opinion—although he told us that he did like a number of Sanrenmu knives, he “refuse[d] to buy the rip off Sebenza,” saying that “there are enough good cheap knives out there that there is no good reason to buy a knock off.” We are more inclined to agree with Jackson, but we understand why some people might avoid the 710.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENTUpgrade pick: Benchmade Mini Griptilian

Upgrade pick

The Mini Griptilian has a steep price tag, but it’s better than the others by nearly every measure. The distinctive blade-locking system and movable pocket clip make this knife fully ambidextrous.

If you appreciate the finessing of all the little details (and have a larger knife budget), we recommend the Benchmade Mini Griptilian. In nearly every way, the Mini Griptilian is superior to our other, less expensive picks. It has a smoother release, which results in the fastest blade deployment you could ever ask for. The blade unlocks with Benchmade’s proprietary Axis lock, which is fully ambidextrous and very easy to use. The grip is contoured and heavily textured, so it will stay in your hand. The blade is made of high-end steel (CPM-S30V), and the lightweight handle offers good balance. All of that comes at a cost, though, as the Mini Griptilian typically retails in the $150 range. Anyone in the knife world likely won’t be surprised to see this recommendation, as the Mini Griptilian has a long-standing reputation as one of the premier folding EDC pocket knives.

As with the Drifter, you deploy the blade of the Mini Griptilian using a thumb stud. The difference is that with the Mini Griptilian, flicking the blade open is nearly effortless. The Drifter is easy and smooth, for sure, but the Mini Griptilian is like silk. Closing the blade has an equal smoothness. Once the blade is past a certain point, it lightly snaps back into the handle (with a very high-quality and satisfying sound). Anyone who owned the Drifter would be unlikely to covet either of these subtle touches, and they’re by no means essential features, but they are nice, and they are the marks of a high-quality knife.

One unique element of the Mini Griptilian is Benchmade’s Axis lock. This design consists of a spring-loaded bar that sits across the body of the blade. Once the blade is fully open, the bar pops forward to lock in place. To unlock it, you pull the ends of the bar away from the blade (the ends look like small thumb studs in the body of the knife).

The Axis lock has a number of advantages over the standard liner lock of the Drifter or the frame lock of the Zancudo and 710. For one, it makes the knife completely ambidextrous. You can operate liner locks and frame locks with either hand, but those designs are unquestionably easier for right-handed people. The Axis lock makes no such distinction, and coupled with the Mini Griptilian’s multi-position pocket clip, it results in a knife that remains fully accessible regardless of your hand dominance.

A second benefit of the Axis lock is that it allows for an additional open/close option. With the locking bar pulled back, the blade sits loosely enough for you to snap it open or closed with a slight flick of the wrist. You don’t even need to touch the thumb stud. Again, this is a great touch, but not essential to the operation of the knife.

The handle of the Mini Griptilian is another high point. Most pocket knives, like our other recommendations, have flat sides, but the Mini Griptilian’s are slightly rounded to fit the hand. It’s a small touch, but noticeable when you’re using the knife. The grip area is also heavily textured along the sides and edges of the handle. We found that once the Mini Griptilian was in our grip, it took a lot for this knife to come out. In fact, if there is a downside, it’s that the handle is too grippy: During our aggressive cardboard-cutting session, the texture along the edges of the knife became uncomfortable.

The handle is made of fiberglass-reinforced nylon. It’s very light, and at first we thought it felt a little cheap for a $100 knife. After having the Mini Griptilian in our pocket for a week or so, we came to like the handle for its overall feel, which was light and durable.

The benefits of the Mini Griptilian don’t stop with the knife itself. Benchmade, the manufacturer, will “clean, oil, adjust and re-sharpen your Benchmade knife to a factory razor sharp edge” at no cost (you’re responsible for the shipping to Benchmade, but not the return shipping).

At around $150 usually, the Mini Griptilian can be a little hard to justify, especially when you can get the perfectly good Drifter for under $40. As reviewer Tony Sculimbrene told us, “Knives are not commodities like milk, so five times the price won't give you five times the stuff.” But still, he added, “You are probably more likely to keep and use a good knife than a cheap one. You are also probably less likely to buy a series of upgrades if you buy a nice knife.” Jackson told us that a cheaper knife and an expensive knife will “both cut the same more or less,” but pointed out that “most people would be able to feel the difference between an $80 Mini Griptilian and a $25 Zancudo.”

In the knife community, the Mini Griptilian is a popular and very highly regarded knife. In a review, Jackson writes, “The Mini Griptilian is an absolutely fantastic EDC option. It’s lightweight, sturdy, and very well made.” He later notes, “Perhaps the only issue is the price. This isn’t a cheap knife, but it is wonderfully made (in the USA) and I think you get what you pay for.”

Also great: Buck Knives 55

Also great

The 55 has none of the modern convenience features of the other knives we tried, but it does have a timeless feel, a comfortable handle, and a durable build quality.

Buying Options

If you simply prefer a more traditional-looking knife, even if that comes at the expense of perks like a one-handed open and close, a textured handle, and a pocket clip, we recommend the Buck Knives 55. The Buck 55 is a small knife, less than 6 inches fully open, but it has a comfortable handle given its size. The brass portion of the frame is thick and sturdy, and the wood accents, made of American walnut, are attractive. We tested ours for about a month as we were writing this review, and the brass bolsters (the protective metal ends of the handle) took on a nice used patina, further enhancing the age-old feel of the Buck 55’s overall design.

The blade of the Buck 55 is under 2½ inches, so it’s not a large knife (it’s actually a half-size version of a classic design, the popular Buck 110). But in this case, the size is a distinct advantage, because without a clip to secure it, the 55 is destined to roam free in a pocket, so it’s nice that this knife doesn’t take up a lot of room, especially when it works its way to the bottom of the pocket and ends up resting across the curve of your leg. The blade size is about as small as we’d want to recommend, but there’s no question that it can cut string, open a package, or free a toy from a blister pack.

The small handle has a simple arcing design that provides a nice grip and is easy to hold in a variety of ways. The texturing is minimal and consists of a light amount of wood grain and three small brass studs per side, but in our tests the knife held firm in our hands. The Buck 55 didn’t have the grab of the Drifter’s G10 handle, but it wasn’t as slippery as the Sanrenmu 710’s polished metal.

The Buck 55 has a clip-point blade, which, functionally, is very similar to a drop-point blade. It has a fine tip for detail cutting, a belly up front for slicing, and a flat edge for dicing and chopping. For the most part, we avoided clip-point blades in our research and testing, because as reviewer Dan Jackson told us, they can appear threatening in a larger knife. But with a total length of 5¾ inches and a cutting edge of barely over 2 inches, the Buck 55 is not a menacing knife. Clip-point blades are also common on this style of traditional folder, and are what many people have come to expect. Because of those reasons, we don’t think blade shape is an issue here.

The Buck 55 opens and closes with a pronounced (and satisfying) snapping noise as the back lock falls into place. The lock itself, positioned at the rear end of the handle, takes two hands to disengage. You could maneuver the knife around and do it one-handed by pressing the lock and folding the knife closed against a leg or some other solid object, but that’s awkward. The Case Mini Copperlock, the other traditional knife we tested, positions the lock at the middle of the handle, so this one-handed operation is easier but still awkward.

The Buck 55’s blade is made of 420HC steel, which is on the lower side of the steel spectrum, but Buck applies a heat treatment that by all accounts puts it up in the range of 8Cr13MoV and AUS-8. Knife Informer’s guide to knife steel says of 420HC: “Still considered a lower-mid range steel but the more competent manufacturers (e.g. Buck) can really bring out the best in this affordable steel using quality heat treatments. That results in better edge retention and resistance to corrosion.”

We tested the Buck 55 against the Case Mini Copperlock, another well-regarded traditional knife, and each has its high points. The two knives are very similar, with nearly identical handle lengths (the blade of the Case is about ¼ inch longer). The Case is a very nice knife, but we preferred the Buck due to the more robust body design and the blade steel. In the end, this comparison was the one instance where the blade steel played a role, as the steel on the Buck held an edge noticeably longer than the Case’s. With all other aspects being so similar, we decided that the Buck was the better option. It’s also typically priced around $10 to $15 less than the Case.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENTThe competition

CRKT also sells a version of the Drifter with an all-metal handle, but both Dan Jackson and Tony Sculimbrene write in their Drifter reviews that they prefer the version with the G10 handle. During our testing, we found all-metal handles slippery.

The Gerber Assert (available in black, grey, or fully customized) is a very nice knife, typically costing around $175. It has the same steel as the Benchmade Mini Griptilian, but it is lighter and thinner. It draws comparisons to the well-regarded Benchmade Bugout and Mini Bugout. While out of the price range we focused on, this is a knife to consider if you’re looking for nice high-end knife.

There is no denying that Spyderco makes excellent knifes. We tested the (now discontinued) Spyderco Dragonfly 2 and Delica 4 (the Dragonfly 2 tops reviewer Tony Sculimbrene’s recommendation list). The handles are extremely comfortable, the knives have good blade steel, and they open easily with a thumb hole. Both models have back locks, though, and as nice as they are, we prefer the liner locks and frame locks of our recommended knives, which are easier to use one-handed especially for someone who might be unfamiliar with knives.

The blade of the Ontario Knife Company's RAT II and RAT I knives are aligned slightly above the handle, and we thought the finger notches on them were too far away from the blade, so we preferred the ergonomics of the CRKT Drifter and Blue Ridge ESEE Zancudo. On the positive side, the RAT II is the best of the sub-$50 knives with a four-position pocket clip, so if that feature is important to you, this knife is a solid option.

CRKT’s Pazoda and Squid are typically less expensive than the Drifter, and both models have robust all-metal bodies and frame locks. But we found the blade deployment on both knives much harder than the buttery feel of the Drifter. With only a few dollars separating them, we think the added investment in the Drifter is worth it.

We can say the same for the Kershaw Atmos, Skyline, and Chill: Each are nicely made, lightweight—the Atmos is under 2 ounces—thin knives with great handles, but we thought thumb-stud designs offered better opening options.

We liked the carabiner clip on the Kershaw Reverb, but in our tests that feature wasn’t enough to offset the difficult open or the awkward liner lock.

Kershaw’s CQC-5K has a small notch at the top of the blade that is designed to catch and deploy the blade as you remove the knife from a pocket. It’s a cool feature, but not an essential one. While the CQC-5K is a durable knife, it has a wider, heavier body than our picks.

Although the Milwaukee Tool Hardline is a smooth flipper, its robust metal body made it really heavy compared with the rest of our test group. It’s built by a tool company, so that heavy-abuse build quality is not surprising, but we don’t think the added weight is necessary for an EDC knife.

The carabiner/bottle opener of the Leatherman Crater C33 came in handy, but overall the handle wasn’t as comfortable as those of our picks, and the blade pivot was not as nice.

The Coast FDX302 feels durable and has a secondary blade lock, but at over 7½ inches it’s a larger knife, and we much preferred the smaller CRKT Drifter.

Aside from the Buck 55, the Case Mini Copperlock was the only other traditional knife we tested. It’s very similar to the Buck and is available in a wide variety of “looks,” but the steel is softer and it’s usually more expensive, so we preferred the Buck.

Reviewer Tony Sculimbrene is a big fan of the LA Police Gear TBFK S35VN, as he named it his best budget blade of 2017. But the blade is over 3 inches and the overall length is 8 inches, so we think it’s on the large side, particularly considering that the CRKT Drifter is so compact.

We dismissed a number of popular knives—including the Kershaw Blur, Cryo, Leek, and Scallion, plus the SOG Flash II—for having an assisted open.

We did not look at the Opinel N°6 for a couple of reasons. First, as Tony Sculimbrene told us, “in general [wood handles] should be avoided” due to the natural swelling and shrinking of the material. In a recommendation roundup at his site, Sculimbrene writes, “I have an Opinel as a camp cooking knife and it is great, but if you leave it out over night, even the dew will make the handle very hard to use.” The Opinel N°6 also has a collar lock, which takes two hands to engage.

Footnotes

The Zancudo is manufactured by Blue Ridge Knives but designed by ESEE, a popular maker of fixed-blade knives. Most knife reviewers as well as the retailer Blade HQ call it the ESEE Zancudo, but a few other retailers, such as Amazon, call it the Blue Ridge Zancudo.

Jump back.The larger the blade is, the larger the handle needs to be. Every ¼ inch of blade adds ½ inch to the total length of the knife, and there is a significant overall size difference between a knife with a 3-inch blade, for example, and a knife with a 3½-inch blade.

Jump back.Knife retailer Blade HQ did a comparison stress test of liner locks, frame locks, and lockback knives, and found that liner locks, on average, could hold 243 pounds of weight before failing, while the frame locks held 277, and the lockbacks held 370. So while liner locks are the weakest of the three, they can still withstand a significant amount of force with a strength that far exceeds your needs for everyday tasks.

Jump back.Assisted-open knives are not switchblades, which is a common misconception. While switchblades are button operated, assisted-open knives are manual, because you have to open the blade before the spring kicks in. Assisted-open knives are not illegal by virtue of the opening system, but in many cities and states, switchblades are.

Jump back.We have a separate guide for knife sharpeners, but those picks are geared toward kitchen knives. Due to the handle design, pocket knives are often not compatible with the pull-through sharpeners we recommend there.

Jump back.The similarities are such that blade reviewers Dan Jackson and Tony Sculimbrene have both raised the possibility that Sanrenmu may manufacture the Drifter for CRKT (but in our interviews, neither claimed to know that for sure). As Jackson noted, “[The] construction [of the Drifter and the 710] is very similar. Same screws, finished the same way - it just looks like it was made by the same company. It’s just a theory, but I would not be surprised to learn if SRM made the Drifter.”

Jump back.

Meet your guide

Doug Mahoney

Doug Mahoney is a senior staff writer at Wirecutter covering home improvement. He spent 10 years in high-end construction as a carpenter, foreman, and supervisor. He lives in a very demanding 250-year-old farmhouse and spent four years gutting and rebuilding his previous home. He also raises sheep and has a dairy cow that he milks every morning.

Further reading

The Best Utility Knife

by Doug Mahoney

The Milwaukee 48-22-1502 Fastback Utility Knife with Blade Storage is an ideal utility knife.

Don’t Open Boxes With Your Kitchen Knives Ever Again! This Utility Knife Breaks Them Down With Ease, And It Helps Tackle DIY Projects, Too.

by Doug Mahoney

The Milwaukee Fastback combines safety and function like no other utility knife.

The Best Carving Knife and Fork

by Tim Heffernan

We carved five turkeys, two beef roasts, a pork roast, and a ham to find an attractive, effective, and reasonably priced carving set.

The Best Knife Sharpener

by Tim Heffernan

Easy to use, reliable, and able to put a razor edge on almost any type of knife, the best knife sharpener for home cooks is the Chef’sChoice Trizor XV.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT