Caroline Bragdon takes the rat’s-eye view of New York City. While tourists stand mesmerized by the skyline and locals focus on safely crossing the street, Bragdon, a research scientist with the health department, keeps her head down. For almost 20 years, she’s kept a close watch on piles of leaky garbage bags, small gaps in the curbs, and oil stains on the sidewalks—all signs of a possible rodent incursion.

On a humid morning in mid-June, Bragdon hits the pavement in the Harlem rat mitigation zone, the latest front in the city’s war against rodents. Sweat glistens on the faces of passersby; Bragdon’s health department–branded moisture-wicking polo works overtime. Here, in this 1.4-square-mile slice of upper Manhattan, 19 staffers (and up to 14 seasonal helpers) respond to complaints, inspect residential and commercial buildings, and educate residents. Armed with spray foam, pest-proof mesh, and buckets full of a black rock called Stalite, they also fill, cover, or otherwise disturb burrows and the lives of the rats inside. “Once they get an edge,” Bragdon says, “they’re gonna just keep burrowing, keep undermining.”

Rats have had an edge in New York—and North America—for almost 300 years. The city’s rodent problem stretches back to the mid-1700s, when the brown rat, a native of Greater Mongolia, set sail in the hulls of commercial and passenger ships and settled on distant shores. Today the species lives on every continent except Antarctica. It dominates most of North America and Europe, from open fields to bustling financial districts. Second to humans, rats are the most populous mammal on earth. While no vermin census is kept, experts estimate that between 500,000 and 2 million rats are currently roaming New York City alone. (The area also has roughly 1,000 licensed pest control companies.) But New York isn’t the only city suffering. Across the globe, from Seattle to Paris to Mumbai, rats are wreaking havoc.

Wild rats make for terrible neighbors, at least by our standards. They are responsible for an unsettling number of household electrical fires. They chew through car wiring and nest inside vehicles. They are linked to bacterial infections and foodborne illnesses, including leptospirosis and salmonella. Children who are chronically exposed to rat droppings in their homes or schools may develop allergies and even asthma. Rats even cause physical injuries: Each year in New York City, an estimated 100 locals report being bitten by rats. What’s more, the mere presence of rats can have a negative effect on mental health. People report feeling afraid and disempowered, their future foreclosed. In one study, researchers found that the psychic toll of rats was worse than the psychological effects of crime.

Rats have always made for splashy headlines. But during the pandemic, as humans retreated indoors, the normally nocturnal creatures took to the streets, terrorizing bystanders. In the Bronx, a man fell through a hole that appeared in the sidewalk—and into a 15-foot-deep warren of rats. “He didn’t want to yell because he was afraid there were going to be rats inside his mouth,” his brother told CBS New York. In Seattle, “cannibal rats”—motivated by restaurant closures and the resulting dearth of garbage to begin devouring one another—made the nightly news.

New Yorkers have always found ways of coping with the rodents underfoot: Ignore them. Track them down and kill them. Or, in the case of “pizza rat,” the viral internet sensation whose visage still graces T-shirts and baseball caps, make a mascot out of them. But in the past few months, this interspecies conflict has hit its historic fever pitch. While researchers aren’t convinced that the number of New York rats has increased, it’s clear that the critters have become more visible—and more brazen—than ever. In 2022, rat sightings by city inspectors doubled, and calls to New York’s 311 hotline from concerned residents reached their highest point in a decade. Sick of sharing their streets with a possibly infectious and sometimes terrifying mooch, residents are demanding more lasting change.

Like many mayors before him, Eric Adams responded to voters’ demands. He hired a “rat czar” to fight what he calls “the real enemy: New York City’s relentless rat population.” Adams selected Kathleen Corradi, a former official with the education department, for the role of coordinating the rat response across city agencies, including the health, sanitation, and parks departments. While other cities are considering giving up the fight—Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo has formed a committee “on the question of cohabitation”—New York is redoubling its commitment. Whether it succeeds in beating back Adams’s sworn enemy remains to be seen.

That’s how Bragdon and her team ended up in Harlem, one of eight zones the city has chosen for expedited rat removal. Here, they practice the latest urban science: integrated pest management, or IPM. Instead of focusing exclusively on extermination, they’re taking a broader view, with the goal of safely and ethically limiting the number of rats born in the first place. By drawing on earlier methods, from European rat hunting to modern chemical warfare, as well as commonsense sanitation principles, they hope to remind the rat who really runs this town.

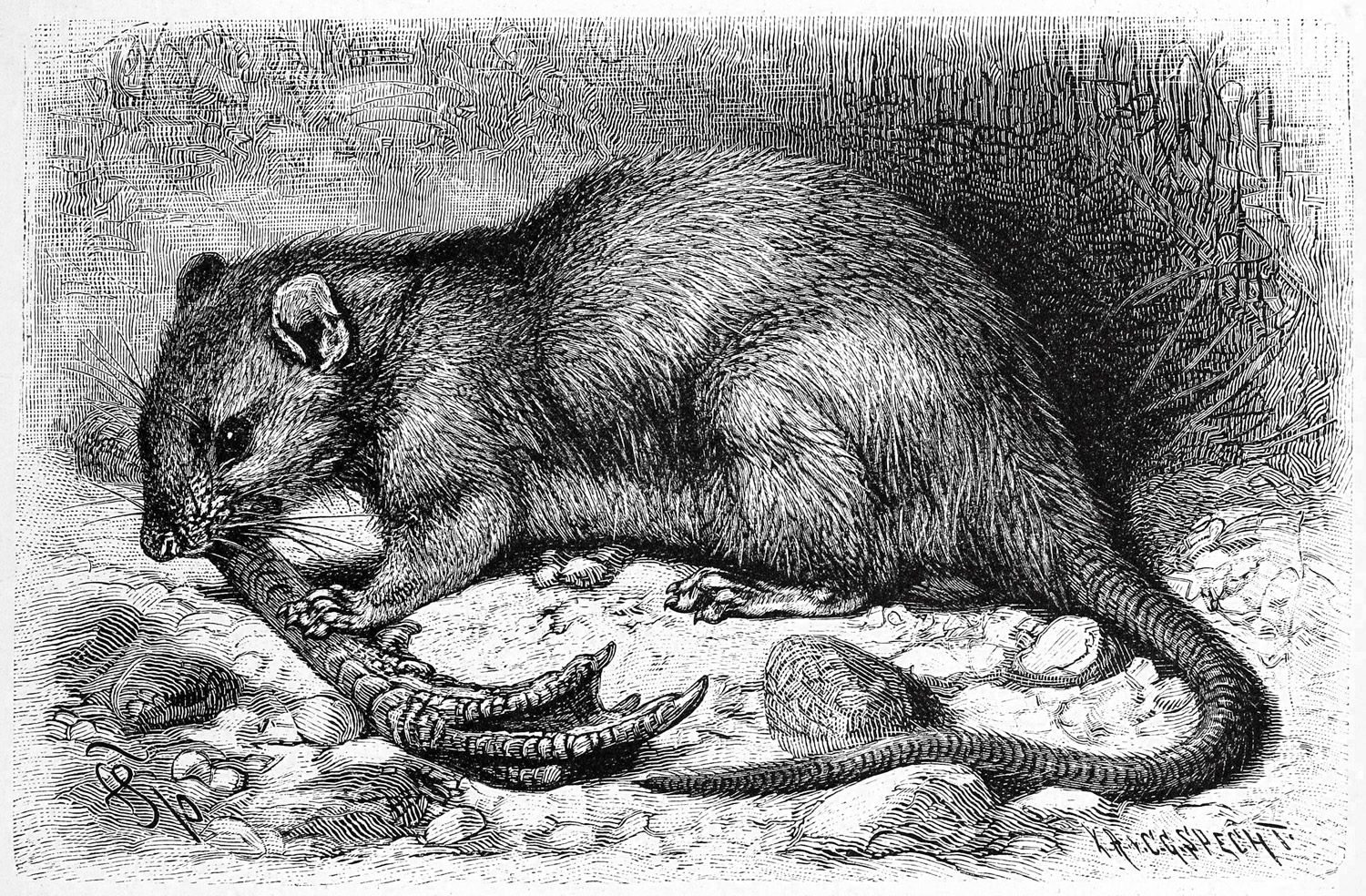

Rattus norvegicus is a marvel of urban evolution. Its furry body can stretch to 11 inches long, with a hairless tail of almost equal length. That tail contains specialized blood vessels that carry heat away from the body; it also helps with balance. A rat’s four-fingered paws are surprisingly muscular, all the better for high-wire acts along tree branches and electrical poles. Three specialized whiskers above its eyes help it sense predators and identify ground cover. All told, most rats weigh between a half pound and a pound—hardly the stuff of urban legend. Bobby Corrigan, PhD, a world-famous rodentologist and consultant, has a standing offer: $500 to the person who can capture the first two-pound brown rat.

One thing that never stops growing? A rat’s teeth. Rodents must chew to keep their incisors in check. Rats, in particular, have a powerful bite. With persistence, they can chew through anything softer than steel—a long list of materials that includes concrete, bronze, and brick. While they are capable of gnawing very large holes, they need only a hole the size of a quarter to slip inside the basement of a restaurant, a subway grate, or an apartment building, and begin feasting.

Rats can survive in the walls of buildings, in subway systems, or even in sewers. But the dominant males, who have the first choice for real estate, prefer to live outdoors. When the guard hairs are brushed back by low-lying plants, rats start digging almost reflexively. The resulting burrows are tucked 18 inches deep into the soil, often under a slab of concrete or into the root system of a tree. They construct long corridors with multiple entryways, ideal for escaping in an emergency. At the center lies the rat’s nest, crafted from strips of paper, fabric, or other cozy items pilfered from humans or nature. All told, a typical burrow can stretch out over three subterranean feet and house five to 10 rats.

The so-called “sewer rat” is widely disparaged, but humans have found other uses for the species. Brown rats are bred as pets (“fancy rats”) with a wide range of coat colors. For more than a century, they’ve also served as the model organism for scientific experimentation. Their biological similarities to humans make them perfect candidates for early-stage drug trials; we share 95 percent of our 30,000 genes with them. Rats are less timid and more intelligent than other animals of similar size. Better still, they reproduce rapidly and require relatively limited resources to sustain themselves. To date, “lab rats” have contributed to breakthroughs in HIV retroviral drugs, cancer drugs, flu vaccines, and more.

In urban contexts, a rat’s reproduction poses serious problems. While the average city rat lives just five months to a year, a healthy female can produce up to seven litters in that small window. Given that each litter can include up to 12 pups, that’s as many as 84 offspring from a single female in a single year. And each of those rats can reach sexual maturity in about eight weeks, after which they begin breeding their own litters. If everything goes right, a single female could see 15,000 of her descendants born in her own short lifetime.

Humans do everything they can to ensure that things go wrong. One of our greatest allies in this centuries-long fight has been the humble canine. Elias Schewel, a Brooklyn-based rat hunter, calls dogs the original “remote sensing technology.” A well-trained dog can sniff out an active rat burrow in seconds, whether it’s in a big, open field or concealed beneath a factory floor. A skilled ratter can also kill any rodent it finds, shaking or crushing the vermin between its jaws. In the 18th and early 19th centuries in Europe and America, rat baiting, in which a dog and captured rats fought to the death in an enclosed ring, was a popular sport before animal cruelty advocates eventually put an end to the practice.

Over time, new methods of pest control emerged. Humans have used deadfall traps (usually a rock, tilted at an angle and held up by branches, which serve as triggers) and snares for millennia. The first spring-loaded mousetrap—immortalized forever in Tom and Jerry episodes—was patented by William C. Hooker of Illinois in 1894. And modern glue traps, which immobilize vermin on a sticky pan of adhesive, hit the market in the 1980s. Electric rat traps lure rodents with bait and then run a deadly high-voltage shock through the chamber. The unlucky rat that walks across a trap-door bucket may be stuck inside—or even plunged into a solution of alcohol. In some cities, electrical traps are merging with internet-connected sensors, not only killing the rat but sending data back to pest managers.

Exterminators rely heavily on rodenticide—a broad category of chemicals marketed for the express purpose of killing rats. Strychnine, which overstimulates the muscles to eventually cause asphyxiation, was once popular. It was replaced in the U.S. by metal phosphides, which cause rapid cell death. In New York today, officials have stashed hundreds of black bait stations, shaped more or less like a pizza peel, in parks, tree pits, and public squares. Each one contains 10 or so packets of a Gatorade-blue rodenticide, strung together like meat on a spit. Rats that chow down will bleed out and die within a week or two—the result of a powerful anticoagulant inside.

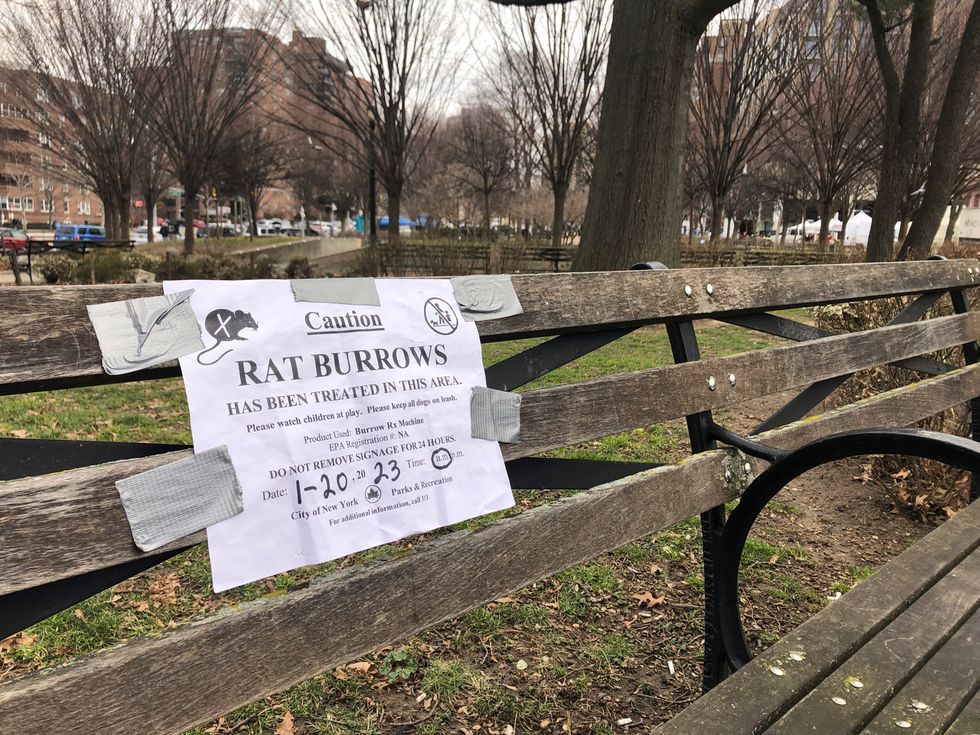

For more targeted attacks on outdoor burrows away from buildings, the city deploys a carbon monoxide machine called Burrow Rx. When Bragdon’s team arrives, they plug the machine into the burrow. Other entrances to the nest quickly become obvious, as smoke-laced carbon monoxide begins to rise. So the health department employees cap those holes, too. Once the entire network is packed tight, they leave the machine running for three minutes, as the concentrated carbon monoxide slowly asphyxiates sleeping rodents.

Every murder method has its pitfalls. Rats are neophobic—a fancy word to describe just how much they avoid new things. It’s hard to entice them to eat bait from a box, or interact with a surface they haven’t touched before. Historically, extermination tactics have often had serious unintended consequences. Birds of prey may inadvertently eat a poisoned rat and end up dying too. In one sample, anticoagulants were found in 84 percent of dead raptors in New York City. And scientists worry that pest control may drive evolutionary adaptation in rats, making them more resilient.

That’s why the most commonsense methods are safer and, officials are betting, more effective in the long run. “You’re not solving the problem,” Bragdon says of methods like rodenticide. A whack-a-mole strategy may be warranted to keep people safe and secure, but the math just won’t add up. Exterminators simply cannot kill rats as fast as the rats are currently breeding. That’s why integrated pest management brings together extermination tools and prevention strategies. Bragdon and some other rat experts are not only decimating existing populations but also creating conditions too hostile for them to return.

On a humid morning just after the Fourth of July, Schewel, the rat hunter, takes his dogs, Sundrop and Moonbeam, out on the job. Together they make up DogTek, Schewel’s for-hire ratting company. Since the start of the pandemic, urban composters have asked the trio to drop by this site in Brooklyn every few weeks. When Schewel, a tattooed, mustachioed millennial in heavy work boots, is not out in the field, he’s buying up prints of 19th century European ratters on Etsy and studying the methods of his peers from England to Utah. The dogs seem eager to hunt. But today’s larger objective, Schewel says, is burrow harassment.

“Burrow harassment” is the city’s preferred term for reminding rats that humans have claims on the same land. It sounds simple, but just filling nests with rocks or sand, digging up or collapsing tunnels, or, in Moonbeam’s case, shimmying into the den itself, can push rats to relocate. While there isn’t a lot of formal research on the method, it’s endorsed by the health department and widely practiced in New York. When combined with the removal of food sources, Bragdon theorizes that the stress caused by burrow harassment may even be enough to curb the rats’ reproduction naturally.

The moment they’re unleashed, Sundrop and Moonbeam fan out across the wedge of land, sniffing wildly. Their keen sense of smell draws them instantly to the perimeter. On one side, rats appear to have burrowed beneath a concrete slab supporting a shed full of rakes and shovels. On the other end of the property, Japanese knotweed, a pest in its own right, has snaked its way through the fence line, providing the perfect cover for vermin.

Today the dogs paw at the area around the garden shed—their way of indicating that they’ve detected an active burrow, fresh droppings, or perhaps a live rat. Moonbeam, a terrier bred for hunting groundhogs, and not much bigger than the biggest rats herself, quickly disappears down into the hole. Sundrop, a tan rescue with a strong herding instinct, circles the shed, waiting to see what, if anything, Moonbeam drives out of the depths below. But they can’t seem to reach the rat.

That’s all right with Schewel. After 20 minutes, he puts a stop to Moonbeam and Sundrop’s mad dash. (One downside of these canine remote sensors? They tend to overheat.) While the dogs haven’t killed anything in a bloody flourish, they have kicked up scraps of plastic, paper, string, plus plenty of bugs—burrow harassment at its finest. “I’m not in the business of selling dead rats,” Schewel says. “I want the survivors to go tell the others what happened here.”

As the dogs rest in the air-conditioned car, Schewel uses a shovel to cover the hole back up. Later he’ll write up a report, telling the owner that the site looks better than it has in years—and recommending another trimming for the knotweed. While integrated pest management has many lessons to offer, the main one is consistency. Rats may be easily driven away, but to keep them at bay takes a more holistic approach.

The brown rat is best understood as a kleptoparasite: an animal that lives by deliberately stealing the food of other animals—in this case, us. But in New York City, rats don’t even have to steal their meals, says Corrigan, the rodentologist. That’s because city slickers deliver rats’ groceries right to their tiny, earthen doors.

Every night around 11 p.m., as the human footsteps and voices die down, the rats emerge, ready to gorge. The average adult rat needs just an ounce of water and an ounce of food per day to survive. A leaky tap and the crumbs at the bottom of a Famous Amos cookie bag, carelessly discarded at a bus stop, can meet the minimum. But in most parts of the city, rats have access to much more. Unlike Amsterdam or Barcelona, where garbage is stored in containers, New Yorkers are infamous for sealing their household and commercial waste in plastic and heaping the bags onto the curb the evening before their scheduled collection. For a nocturnal scavenger like the brown rat, this garbage disposal system couldn’t work better.

When darkness descends, rats are focused on foraging. As a rule, they make their nests within 100 or so feet of a reliable food source. Corrigan, who’s usually clad in khakis, a button-down, and his city-mandated safety vest, has watched their nightly ascents too many times to count. Rats have terrible eyesight, so they allow their extraordinary sense of smell to be their guide. Their noses work in stereo, processing scents from the left and right nostril separately but simultaneously, allowing them to pinpoint the source of an odor in milliseconds and with radar-like accuracy. Rats will eat whatever it takes to survive, but like Remy in Ratatouille, they will go out of their way to secure their favorite late-night bites. “The rats do know high-quality foods,” Corrigan says.

Like humans, rats enjoy takeout meals. After about 45 minutes rooting around in torn bags and crawling into dumpsters, they drag their meals back to their burrows. There, rats eat, play, nap, and clean themselves and each other. They’re ticklish—and giggle (ultrasonically) as a way of bonding with one another. They love to wrestle for fun. They mate with fervor—up to 100 times a night when a female is in heat. Around 4 a.m., Corrigan says, rats will emerge once more for their version of the midnight snack, before settling down to sleep around sunrise.

Like tourists in Times Square or buskers in the subway, evidence of the brown rat’s nightly feeding frenzy has become a part of the fabric of the city. It’s difficult to see at first, but to a trained eye, the oval holes chewed through plastic garbage cans are obvious, as are the chicken bones picked clean and tugged to the edge of a construction site. Against the concrete, Corrigan can even spot hard black pellets of poop. But the nightly rat buffet—and its unappetizing aftermath—didn’t always exist here. One day it will be contained again, if Bobby Corrigan has anything to say about it.

As a kid growing up in Brooklyn, Corrigan remembers New Yorkers placing their garbage in metal cans—the direct inspiration for Oscar the Grouch’s humble abode. They were sturdy and not easily chewed through, and they came with lids that, if properly fastened, offered a tight seal. In 1971, however, New York City Council opted to ditch containerization and allow residents to place the newfangled plastic bag technology directly on the street.

To sanitation workers, plastic seemed like the innovation of a lifetime. Trash bags were lighter and easier to move than cans; collection moved at a faster clip. But some pest management experts—and Corrigan, then just a student—were horrified. Rats, raccoons, or any other determined animal could rip right through the bags and feast on what they found inside. Their worst fears were proven correct: In 1969, a survey found rats in 11 percent of the city. Today, by Corrigan’s estimate, they’ve infiltrated up to 90 percent of New York.

That’s why Corrigan, a pest management consultant to cities across the country, believes a lasting change will require New Yorkers to clean up their act. “No garbage,” Corrigan says, “no rats.” But containerization has proved difficult. In the mid-2010s, New York began piloting the Bigbelly, a fully enclosed trash-compacting bin by the dozen. The containers, each $7,000, now number around 850 in the city’s five boroughs. The Bigbelly has helped curb rat populations on college campuses and in local parks from Seattle to Washington, D.C., Corrigan says. But in New York, they are regularly damaged beyond repair—attacked by angry pedestrians, rammed by scooters, struck by vehicles, and jammed up with garbage. In some neighborhoods, they’ve been replaced with the old open-top garbage cans of yore.

When it comes to household garbage, containerization remains something of a political third rail. In 2023, Mayor Eric Adams’s administration released a report showing that replacing plastic bags was feasible for 89 percent of the city. But binning trash would cost hundreds of millions of dollars and require the sanitation department to dramatically increase the frequency of trash collection. It would also eliminate 150,000 street parking spots—to be filled with the closed containers. “150,000?” one man asked This American Life, incredulously. “Where are they gonna park? In Jersey?”

So Corrigan, Bragdon, and others are promoting individual-level sanitation solutions in the interim. Through one-on-one conversations with restaurateurs, health department inspections, and Rat Academy (a free Zoom or in-person rat-prevention class for community members), they spread the gospel of integrated pest management. They advise renters and owners to trim back plants, fill ratholes with pest-proof mesh and spray foam, and contain whatever garbage is in their control. Only when everything else fails does the health department call in the big guns—or, in this case, the big tubes that deliver rat-killing carbon from the Burrow Rx.

Mitigation may not be Corrigan’s first-choice solution; he’d like to see a more radical intervention. But for now, grassroots action is the best chance New York has to beat back the rats. “It’s not about more poisons. It’s not about more exterminators,” Corrigan says. It’s about learning to be “good stewards.”

New York City will never be free of rats—at least not until it’s free of humans. “They’re just there because of our filth,” says Michael Parsons, an urban ecologist at Fordham University and a veteran rat researcher. Like cockroaches, pigeons, and a handful of other pests, rats thrive on a planet made increasingly inhospitable by Homo sapiens. Things that would normally crush a species are, in the brown rat’s tiny pink hands, an opportunity. They’re adapting to our extermination methods and surviving on our trash. Climate change has already initiated a sixth great extinction, but rising temperatures have only extended the rat’s breeding season.

City officials and scientists can envision a future in which local rat populations are brought back down to their pre–plastic bag levels—or even lower. If rats don’t have access to human food, Parsons says, the rodents would adapt to their new caloric landscape by breeding less and fighting among themselves for dominance. Rather than being a constant menace, rats would be reduced to “remnant populations,” which would be easier to track and contain. Corrigan has already deployed countless sensors in bait boxes to track rats throughout the city. Placed strategically, in schools, hospitals, and other areas of special concern, he believes the devices will identify the rumblings of a rat renaissance—and allow exterminators to stop an infestation before it happens.

With rats under control, the city would undoubtedly be a better place for humans. Restaurant kitchens would be cleaner. Homes and schools would be safer, especially for kids, who could grow up breathing easy. Garbage collection would be tidier, and the streets cleaner each morning—much like they are in other cities around the world. Most important, residents would be free from the tyranny of a four-legged menace. Those currently feeling ashamed or afraid might find a newfound pride in their community. And applying integrated pest management to rats may help us prepare for future battles. (The one infestation Corrigan thinks is worse than rats? “Mice.”)

Back in Harlem, Bragdon already sees signs of improvement. A few restaurants have taken down their rat-infested dining sheds. A resident is eager to tell her he’s taken Rat Academy not once, but twice. But there are other, more dispiriting moments, too. Bragdon watches helplessly as a woman rips up a half a loaf of bread and dumps it on the sidewalk, presumably to feed birds—but almost certainly feeding rats instead. She clocks multiple public trash cans overflowing with waste dumped there illegally by nearby businesses, and two community gardens studded with ratholes.

The key, Bragdon says, is helping people to understand that if they see a rat in their neighborhood, that is their rat. It lives under their sidewalk and survives on their garbage. It may be easier to blame a neighbor, or the restaurant down the block. But just as every New Yorker has, inadvertently, helped to create and sustain the problem, Bragdon says, “everyone has a role in the solution.”

Eleanor Cummins is a freelance science journalist in Brooklyn whose work can be found in The Atlantic, The New York Times, National Geographic, The Verge, WIRED, and more. She is also an adjunct professor at New York University’s Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program.