Depression

Honey, I Squished the Kids’ Heads!

Messing with babies’ heads has arisen multiple times around the world.

Posted June 13, 2016 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

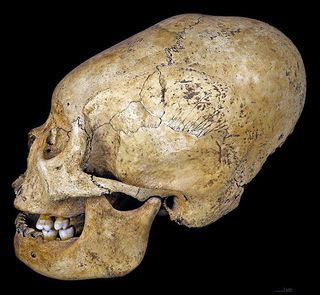

Head binding to change the shape of a baby’s head is surely one of the most radical forms of socially imposed body modification. Tightly binding an infant’s head produces highly unusual skull patterns that anthropologists call artificial cranial deformation. Because the most striking and best-known examples are found in South America, it is commonly thought that skull deformation is a puzzling occurrence limited to that part of the world. Indeed, extreme cases of skull warping in South America have repeatedly given rise to wild claims about alien intervention. In combination with the enigmatic Nazca lines (“only visible from outer space”), weirdly shaped human skulls from Paracas and Nazca in Peru have particularly helped to fuel such fanciful stories.

Reshaping a baby’s head

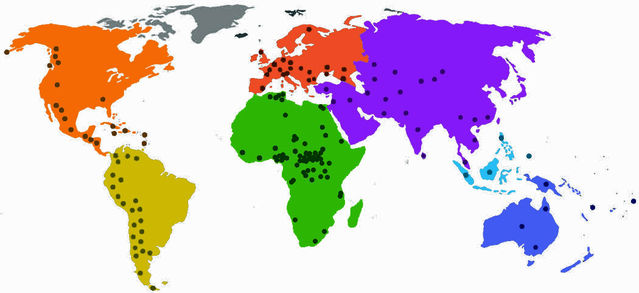

Although permanent skull deformation brought about by deliberate binding of an infant’s head has been particularly well reported from South America, it is actually found around the world. Most cases are documented only by archaeological evidence, although in some places the practice of head binding continued until quite recent times. Inhabitants of Toulouse (France) were still binding children’s heads to make them longer up to the early part of the last century, while coastal islanders in southern Malakula Island (Vanuatu) continued a similar practice almost to the close of the century.

Radical head deformation must be accomplished early in life, while an infant’s skull is still flexible. The elaborate procedure usually begins soon after birth and continues for several months, sometimes as long as two years. Distinctive head shapes produced by head binding vary widely from place to place, but they tend to fit a particular pattern at any one site at a given time. Shapes range between tall profiles with front-to-back flattening and extremely elongated forms. Soft bandages (commonly made of cloth) are almost universally applied to alter head shape, and in many cases, pieces of wood are used as well to achieve flattening in the desired places. Because artificial cranial deformation requires a months-long process of head binding, its origin is enigmatic. What makes it even more puzzling is that this cultural practice clearly arose independently in numerous places around the world. Although some traditions may have spread by migration, as has been suggested for the Bering Strait migrants that populated the Americas, it clearly developed in isolation in many other places with no evidence of prior history.

At first sight, it seems highly unlikely that such a complex cultural practice with broadly similar outcomes could have arisen so many times independently. But there is a fairly simple explanation. In many cultures, including several modern societies, infants are carried around strapped to cradle boards. Immobilizing infants’ heads on a rigid board on a daily basis over long periods can inadvertently lead to deformation. I came across striking evidence of this in the collections at The Field Museum in Chicago while examining certain human skulls from populations using cradle-boarding. Because the skull shape was irregular it was pretty obvious that the outcome was unintentional. With deliberate head binding the resulting skull shape is usually neatly symmetrical.

Questions about head warping

The most obvious question to ask is: “Why did so many different human societies independently hit upon the idea of binding infants’ heads to produce a distinctive shape?” As many cases are known only from archaeological studies, it is difficult to answer this with any certainty. However, the most frequent—and also the most likely—explanation to be offered is that a distinctive head shape was contrived as a badge of rank. This is, for instance, indicated by the fact that artificial cranial deformation was seemingly typical of administrators in the Mayan empire. But this is not always the case. Head binding in Toulouse, for example, was reportedly prevalent among the lower class. Possessing a distinctive head shape is in any case a very effective way of emphasizing differences between groups of people, and it sometimes has fairly obvious connections with mythology or religion.

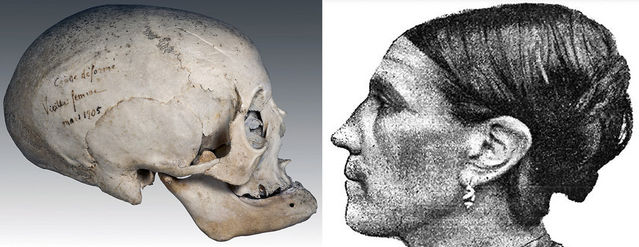

Another understandably common question is “Does head binding adversely affect the skull or brain?” The pioneering French anthropologist Paul Broca (renowned for his recognition of a key language center in the human brain) believed that skull deformation altered certain human capacities. And some believed that Toulouse peasants who practiced head binding suffered from diminished intelligence. However, numerous studies have indicated that head binding has only negligible effects on the skull itself and that the inevitable modification of brain shape has no unfortunate side effects. As long as the volume of the brain is unchanged, its functioning seemingly remains unimpaired. An oft-cited 1989 paper by Susan Antón reviewed changes in the skull base and facial shape accompanying artificial deformation in three different Peruvian populations. Marked changes in dimensions were identified, but the basic structure of the skull remained unaffected. A follow-up 1992 publication by Antón and colleagues specifically examined the junctions between bones (sutures) in artificially deformed skulls. Minor differences were found, depending on the type of deformation involved. Particularly with skulls with front-to-back flattening, more accessory bones were found along the sutures between the main bones at the back of the skull, probably an outcome of general broadening. This suggests that head binding causes little modification in the growth of sutures and confirms the impression that there are no profound effects on either skull growth or brain function.

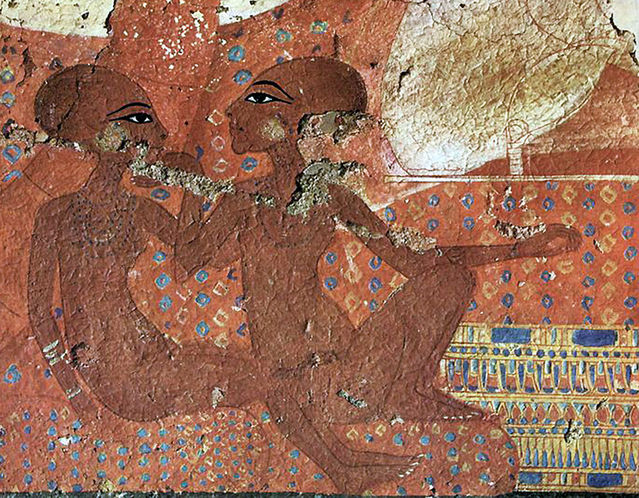

Head binding in Ancient Egypt?

There have been several suggestions that head binding also occurred in Ancient Egypt, notably during the 18th Dynasty. Various murals and sculptures indicated that Akhenaten and Nefertiti had unusually elongated head shapes and that the same was true of Akhenaten’s six daughters (Merytaten, Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten, Nefernoferuaton Tasherit, Nofernoferure, Setepenre) and of his son Tutankhamun. And it is now known from studies of the mummies that the skulls of both Akhenaten and Tutankhamun did indeed have distinctively elongated shapes. In the case of Tutankhamun, a saddle-shaped depression on top of the skull together with a complementary depression under the rear end closely matches well-documented effects of head binding in other regions. It is interesting that extreme head elongation was the favoured outcome. However, there is no clear evidence of head binding before or after the reigns of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun.

In fact, egyptologists have generally dismissed the possibility of head binding in Ancient Egypt. The elongated heads in murals and sculptures are interpreted as stylistic exaggeration accompanying the public representation of Akhenaten and his family at El-Amarna. And artificial cranial deformation has been ruled out on the grounds that no records of such a practice have ever been found, despite the extensive documentation available for many other customs. The occurrence of strangely shaped skulls has been unconvincingly attributed to an inherited condition stemming from Akhenaten.

For the time being, the question of head binding in Ancient Egypt remains unresolved, although the distinctive skull shapes of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun do provide tantalizing pointers. In fact, recent scanning studies of Egyptian mummies conducted by JP Brown and myself at The Field Museum have revealed that mild cranial deformation was apparently present in Minirdis, the son of a Stolist priest from Akhmim. Perhaps this cultural practice also occurred during the Early Ptolemaic Period at Akhmim, which was an important religious center.

Alien intervention?

Quite clearly, the strikingly elongated human skulls found at sites such as Nazca and Paracas in Peru are simply extreme cases of the well-documented practice of head-binding. Nevertheless, the wild notion that those strange skull shapes are a result of alien intervention remains stubbornly persistent. In a recent twist on this outlandish interpretation, it has been claimed that DNA extracted from deformed skulls from Paracas is significantly different from normal human DNA. As yet, no details have been published in a respectable peer-reviewed journal. Don’t hold your breath.

References

Antón, S.C. (1989) Intentional cranial vault deformation and induced changes of the cranial base and face. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 79:253-267.

Ayer, A., Campbell, A., Appelboom, G., Hwang, B.Y., McDowell, M., Piazza, M., Feldstein, N.A. & Anderson, R.C. (2010) The sociopolitical history and physiological underpinnings of skull deformation. Neurosurgical Focus 29(6),E1:1-6.

Barras, C. Why early humans reshaped their children’s skulls. http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20141013-why-we-reshape-childrens-skulls

Cheverud, J.M., Kohn, L.A.P., Konigsberg, L.W. & Leigh, S.R. (1992) Effects of fronto-occipital artificial cranial vault modification on the cranial base and face. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 88:323-345.

Childress, D.H. & Foerster, B. (2012) The Enigma of Cranial Deformation: Elongated Skulls of the Ancients. Kempton, IL: Adventures Unlimited Press.

Dingwall, E.J. (1931) Artificial Cranial Deformation: A Contribution to the Study of Ethnic Mutilations. London: John Bales, Sons & Danielsson.

El-Najjar, M.Y. & Dawson, G.L. (1977) The effect of artificial cranial deformation on the incidence of wormian bones in the lambdoidal suture. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 46:155-160.

Enchev,Y., Nedelkov, G., Atanassova-Timeva,N. & Jordanov,J. (2010) Paleoneurosurgical aspects of Proto-Bulgarian artificial skull deformations. Neurosurgical Focus 29(6),E3:1-7.

Kiszely, I. (1978) The origins of artificial cranial deformation in Eurasia from the sixth millennium BC to the seventh century AD. British Archaeological Reports International Series (Supplement) 50:1-76.

Obladen, M. (2012) In God's image? The tradition of infant head shaping. Journal of Child Neurology 27:672-680.

Ricci, F., Fornai, C., Tiesler Blose, V., Rickards, O., & Manzi, G. (2008) Evidence of artificial cranial deformation from the later prehistory of the Acacus Mts. (Southwestern Libya, Central Sahara). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 18:372-391.