Identity

Strange Head Shapes: Revisiting Nefertiti, Akhenaten and Tut

Squeezing heads into bizarre shapes has many origins, including Ancient Egypt.

Posted July 30, 2019 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

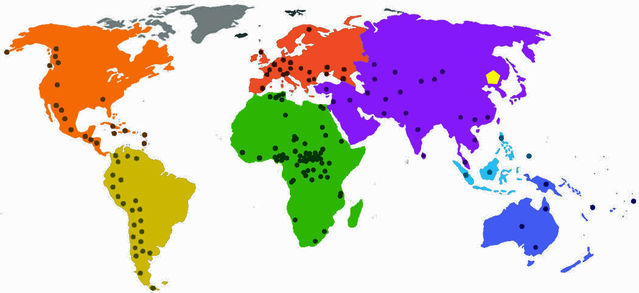

Two reports from China prompted me to revisit head binding — intentionally molding babies’ heads into strange shapes. (See my blog post from June 13, 2016, Honey, I Squished the Kids’ Heads!) Known to anthropologists as artificial cranial deformation, this is a particularly striking kind of permanent body modification. Examples have been reported around the globe. However, head binding clearly did not arise at a single site but independently in many different places. It is elaborate, requiring careful binding of a baby’s head for several years. So how can we explain so many multiple origins?

Multiple origins

The worldwide distribution of head binding includes well-documented examples from North and South America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Many cases are known only from archaeology, but some are historically recent. Systematic head binding is well known for the Mangbetu, a Congolese people, and Wikipedia enigmatically states that its origin “dates back to Ancient Egypt.” However, head binding generally occurs sporadically in just a few localized populations, apparently without direct connections.

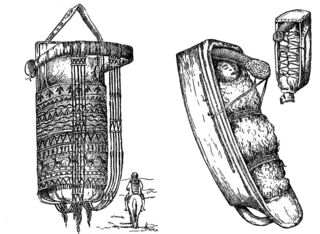

At first, it seems improbable that such a complex custom could have originated independently so many times. As my 2016 blog post suggested, however, baby-carrying devices provide a plausible common origin. In many societies, babies have been carried tightly strapped to a cradleboard. This is particularly well-documented for Native Americans, notably the Algonquin peoples, who originally occupied a vast range in Canada and the USA. Skulls of Native Americans carried on cradleboards as children are often deformed. Left and right halves of the skull typically differ markedly in shape and this asymmetry indicates that it was unintentional.

Evidence from the Chinookan peoples — inhabitants of a small geographical region in the Pacific Northwest of the USA, along the Columbia River — reinforce the proposed connection between cradle-boarding and intentional head binding. Certain Chinookan tribes used a modified cradleboard with an additional small board tightly bound across the forehead. The 1993 book Indian Slavery in the Pacific Northwest by Robert Ruby and John Brown reported that head binding was confined to high-ranking tribe members. Individuals with flattened skulls would not enslave others with similarly shaped heads, while round heads signified subordinate status.

Head binding in northeastern China

So now to those two recent reports from China. Previous world maps showing where head binding occurred included only a few cases for China and none at all in the northeast. In the first paper, Xijun Ni and colleagues reported finding at a site on the Songhua River (Heilongjiang Province) an adult male braincase clearly displaying intentional deformation. The partial skull, dated at over 11,200 years ago, was the earliest-known case of head binding from Asia.

The second paper on intentional skull modification from northeastern China, authored by Qun Zhang and colleagues, reported several deformed human skulls from Houtaomuga (Jilin Province). Measurements indicated that over half — 11 out of 19 — showed signs of deliberate deformation. Three types were identified, but front-to-back flattening was most common. Identified cases notably covered an extensive 7,000-year period (5,000-12,000 years ago). Analyses of artifacts and ancient DNA indicated cultural and genetic continuity, suggesting a long-standing tradition of skull deformation.

Changes in head binding over time

A 2018 report by Matthew Velasco provides a finer-grained understanding of how head binding develops over time. Velasco tracked changes in intentional cranial modification in the Collaguas — a single prehispanic population inhabiting the Colca Valley in the Peruvian Andes. His survey covered the “Late Intermediate Period” (1100–1450 AD), sandwiched between the collapse of the Wari and Tiwanaku states and the rise of the Inka Empire.

Assessing skull shapes relative to a series of radiometric dates, Velasco distinguished early and late phases (1150-1300 AD versus 1300-1450 AD). Skull deformation frequency rose significantly between the two phases, almost doubling from 39% to 74%. This sharp increase was associated with increased standardization of head-shaping practices. Whereas four different forms of cranial modification occurred at roughly equal frequency during the early phase, an oblique skull vault shape predominated during the late phase, accounting for 63% of cases.

Velasco went on to explore potential implications for collective identity among the Collaguas. He suggested that the observed trend in head-binding practices may have facilitated cooperation between elite groups during a time of pronounced conflict. He also proposed an association with mounting social inequality prior to Inka imperial expansion. Various studies have indicated that higher frequencies of artificial cranial deformation usually reflect greater social control, reinforcing identity across an extensive social network.

Head binding in Ancient Egypt

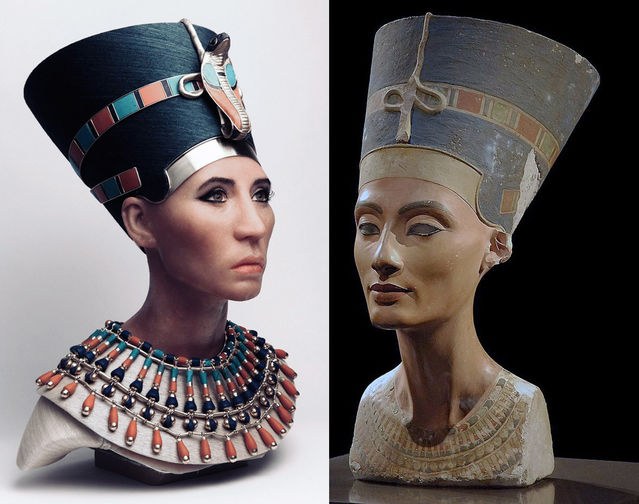

Given the extensive yet sporadic occurrence of intentional skull modification through head binding, this practice may explain the unusual head shapes of the Pharaoh Akhenaten and his immediate family: his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti, all of their six daughters, and his son Tutankhamun. Numerous statues and reliefs indicate conspicuous head elongation in all, although this has often been attributed to a new artistic convention.

Rejecting the possibility of head binding, Egyptologists have generally favored some kind of (possibly inherited) medical syndrome when explaining strange head shapes in the Akhenaten family. Following the dismissal of an early suggestion that Akhenaten suffered from hydrocephaly (usually fatal early on without sophisticated medical intervention), attention turned to Froehlich's Syndrome, which severely disrupts the body’s hormone balance. But that syndrome, which leads to infertility, clashes with Akhenaten’s undisputed array of offspring. A more recent prime candidate has been Marfan’s Syndrome, which at least does not entail early death and may allow fertility. But all such proposals share a fatal flaw: No pathological condition is likely to cause symmetrical head deformation.

A formidable obstacle to any interpretation of head shapes in Akhenaten family members is confusion about their relationships and the identities of various mummies. One current suggestion is that Nefertiti was Akhenaten’s sister and gave birth to Tutankhamun as well as the six daughters. It is generally accepted that one daughter (Ankhesenpaaten) eventually became Tutankhamun’s wife. Also undisputed is the identity of the mummy attributed to Tutankhamun. On the other hand, mummies from the Valley of the Kings have been identified only tentatively as Akhenaten (possibly KV55) and Nefertiti (maybe “Younger Lady," KV35YL). Making matters worse, Nefertiti’s origins and ultimate fate are shrouded in mystery.

My own keen interest in Ancient Egyptian head shapes was triggered by a Tutankhamun bust crafted by French artist Elisabeth Daynès, sculptress of superb head reconstructions using meticulous application of forensic principles. On first seeing a side view of Elisabeth’s bust of Tutankhamun, I immediately realized that his head must have been tightly bound early in life. Adding to his elongated, flat-topped head shape, a telltale small depression on the crown corresponded to a depression close to the back of the neck. The bust convincingly matches the skull shape reconstructed from a CT-scan. The KV55 skull — whoever its owner may have been — shows a very similar shape, although the head has yet to be reconstructed.

Last year, filling a major gap, Elisabeth Daynès was commissioned to create a forensically-informed head reconstruction of the Younger Lady, based on a cast of the mummified head, which also shows a conspicuous elongation. In sum, regardless of the true identities of the mummies KV35YL and KV55, there is convincing evidence of intentional head shape modification for several individuals. But this practice was apparently confined to two generations, one corresponding to Akhenaten and Nefertiti and the other to their daughters and Tutankhamun.

An accidental modern counterpart

Ironically, although the practice of head binding has widely been abandoned, an accidental type of shape modification is now becoming common. The pediatric community, after causing tens of thousands of needless child deaths with an ill-advised recommendation to have babies sleep on their stomachs, abruptly reversed course in the early 1990s, with beneficial results. However, slavishly constraining babies to sleep on their backs for extended periods has had the unwelcome side-effect of deforming their heads. In a condition known as plagiocephaly, the back of the head becomes flattened, and — as with cradleboarding — the resulting shape is typically asymmetrical because it is accidental. Modern human babies often wear helmets, the modern equivalent of head binding, to correct the unwanted distortion.

References

Enchev, Y., Nedelkov, G., Atanassova-Timeva, N. & Jordanov, J. (2010) Paleoneurosurgical aspects of Proto-Bulgarian artificial skull deformations. Neurosurgical Focus 29(6),E3:1-7.

Hawass, Z.A., & Saleem, S.N. (2018). Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press.

Martin, R.D. (2017) Why did King Tut have a flat head? BrainScoop interview with Emily Graslie [approaching 3 million views]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L54f8Ok1Z5w&t=171s

Mason, O.T. (1887) Indian cradles and head flattening. Science 9:617-620.

Ni, X., Li, Q., Stidham, T.A., Yang, Y., Ji, Q., Jin, C. & Samiullah, K. (2019) Earliest-known intentionally deformed human cranial fossil from Asia and the initiation of hereditary hierarchy in the early Holocene. bioRxiv.

O'Brien, T.G. & Stanley, A.M. (2013). Boards and cords: Discriminating types of artificial cranial deformation in prehispanic south central Andean populations. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 23:459-470.

Ricci, F., Fornai, C., Tiesler Blose, V., Rickards, O., & Manzi, G. (2008) Evidence of artificial cranial deformation from the later prehistory of the Acacus Mts. (Southwestern Libya, Central Sahara). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 18:372-391.

Risse, G.B. (1971) Pharaoh Akhenaton of Ancient Egypt: Controversies among egyptologists and physicians regarding his postulated illness. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 26:3-17.

Ruby, R.H. & Brown, J.A. (1993) Indian Slavery in the Pacific Northwest. Spokane, WA: Arthur H. Clark Co.

Snorrason, E. (1946) Cranial deformation in the reign of Akhenaton. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 20:601-610.

Velasco, M. (2018) Ethnogenesis and social difference in the Andean Late Intermediate Period (AD 1100-1450). Current Anthropology 59:98-106.

Zhang, Q., Liu, P., Yeh, H.-Y., Man, X., Wang, L., Zhu, H., Wang, Q. & Zhang, Q. (2019) Intentional cranial modification from the Houtaomuga Site in Jilin, China: earliest evidence and longest in situ practice during the Neolithic Age. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 169: 747-756.