Key Concepts

Geology

Weathering

Physics

Chemistry

Introduction

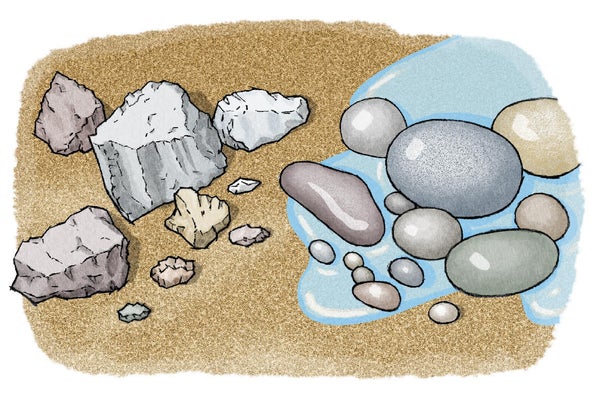

Have you ever visited a canyon or cave and wondered how those formations came to be? Or observed smooth stones by a river or beach? These results are due to a process called weathering. Weathering, or the wearing-away of rock by exposure to the elements, not only creates smooth rocks as well as caves and canyons, but it also slowly eats away at other hard objects, including some statues and buildings. Try this process out on a sugar cube and feel how powerful weathering can be.

Background

Rock might seem permanent, but it is actually constantly being broken down. We often do not notice this process because it happens so slowly. As soon as rock is exposed to the elements it can start being broken down through the process of weathering. Scientists categorize this processes into two groups: physical weathering and chemical weathering.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Physical weathering (also called mechanical weathering) happens when physical forces repeatedly act on the rock. One example is rocks tumbling over one another, knocking off pieces from one another. This often happens in a river, desert or hillside.

In chemical weathering the rock disintegrates or even dissolves because a chemical reaction changes the composition of the rock. When certain types of rock come into contact with rainwater (which is often slightly acidic, especially when there is pollution present) a chemical reaction occurs, slowly transforming the rock into substances that dissolve in water. As these substances dissolve they get washed away. It is almost as if the rock has vanished!

In this activity you will model physical and chemical weathering with sugar cubes—so you can see it happen before your eyes.

Materials

At least four sugar cubes

Water

Dark colored paper or countertop

Glass

Dropper

Work area that can get wet

Towel for cleaning up (optional)

Clay (optional)

Spray bottle (optional)

Frosting (optional)

Nail file (optional)

Tray or large dish with sides (optional)

Preparation

Gather your materials in a location that can get wet.

Procedure

Think of a few ways you can break or pulverize your rock (sugar cube) with mechanical weathering.

Try it out with one of your sugar cubes!

Did you crush it, smash it or apply another force on it?Can you list examples of how rocks get smashed or crushed in nature?

Now take two new sugar cubes, and grind one against the other over a dark colored piece of paper or countertop. What happens? Do you see sugar dust on the paper or countertop? What is happening to your rock (sugar cube)?

Try rounding the edges of your sugar cube this way. Does it work?

Look back at what is left of your sugar cube. What does it look like? Is it still sugar?

Now take a new sugar cube. What are some ways you could break down your rock (sugar cube) with chemical weathering?

In this activity we’ll use water drops to simulate rain. Place the sugar cube in a glass.

Fill your dropper with water, and squeeze a few drops on the sugar cube. Look and feel to observe what happens.

What do you think will happen if you drop more water on the sugar cube?What do you think would happen if you drop 10 or 100 (or more) drops on the sugar cube? Will it still be a sugar cube? Will it still be sugar?

Drop more water on your sugar cube. Where does the sugar go? Can you make the cube disappear completely?

Extra: Place a few sugar cubes in a glass. Cover them with clay. The sugar cubes represent a layer of rock, and the clay represents topsoil. Make a few holes or a crack in the clay so rainwater can seep into the ground and reach the layer of rock. Spray water over your glass, representing rain coming down over your piece of land. What do you think will happen to your layer of rock? Might caves form? How does this process depend on having different types of materials in the ground?

Extra: Make a sugar-cube sculpture or structure. To glue cubes together, wet one side of the cube and press it against another cube. If you need stronger glue, frosting can do the trick. Make sure your sculpture has some details and sharp edges. A nail file can help you sculpt the cubes. What do you think will happen to your sculpture when it is exposed to rain? Place your sculpture on a tray or dish with sides, and use a spray bottle to let it rain over your sculpture. First a little—then more. What happens? Look carefully at the details and edges: Do they change? What will happen eventually after a lot of rain? This is exactly what acidic rain can do to some statues and buildings over time.

Observations and Results

Was breaking a sugar cube by smashing, crushing or grinding it easy? Rock breaks down in a similar way—but a lot more slowly—in nature in this process of physical or mechanical weathering. Forces in nature, such as gravity, wind and even the push of freezing water or plant roots, impact rocks. These forces eventually wear the rock down. The result is smaller pieces of rock—just like you were left with smaller pieces of sugar.

What about your chemical weathering test? Did the sugar cube become weak and eventually dissolve in the drops of water? That happens to some types of rock, too. Some minerals in rock react with liquids or gasses, creating new substances, which are often weaker—and sometimes even dissolve in water. After you applied enough water you probably did not have any sugar cube left as it was carried away with the water. In a similar way rocks can dissolve and be washed away, forming caves.

If you tried to build a sugar statue and exposed it to water, you probably saw it slowly disappear. This happens to some statues and buildings—and at a faster rate when more pollution makes the rain more acidic.

More to Explore

Weathering, from The Geological Society

Weathering, from National Geographic

Holey Porous Rock Science!, from Science Buddies

How Dirt Cleans Water, from Scientific American

STEM Activities for Kids, from Science Buddies

This activity brought to you in partnership with Science Buddies