- The dwindling community, which has only 100 practising members in Henan province, was established in AD600

- After learning of their existence online, an 18-year-old schoolboy with no Jewish heritage went on a voyage of discovery

The Jews of Kaifeng do not have a rabbi, or a synagogue. Their last religious leader died more than 150 years ago, and their last place of worship was destroyed by flood at around the same time.

To some in Kaifeng, Jews are “blue-capped Muslims”, the colour of their skull caps, if not their specific religious identity, acting as a distinguishing feature. To others, they are “the sect that plucks out the sinews” – a nod to the Jewish custom of removing the sciatic nerve from kosher meat.

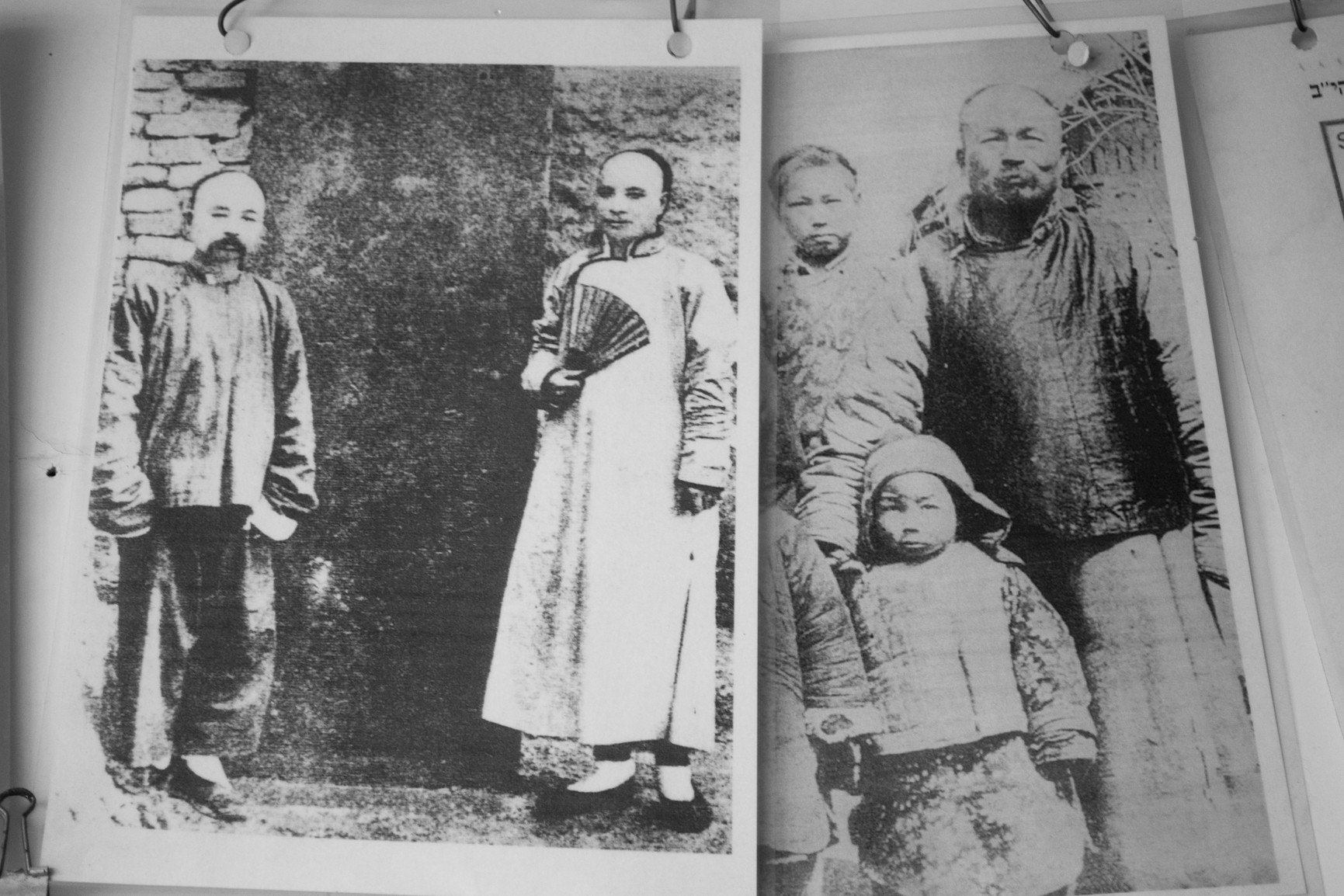

And though they have their own modest museum, they are also far from the beaten tourist track. Visitors turn up no more than once every month or two.

In recent years, however, the Kaifeng Jews have found the most surprising of ambassadors determined to keep their history alive: a Hong Kong teenager studying at a British boarding school.

Eighteen-year-old Nicholas Zhang – who grew up near the University of Hong Kong, the son of bankers – has no Jewish ancestry. So what on Earth is he doing at the Limmud Festival, Europe’s largest Jewish educational event, in Birmingham, Britain, talking about his passion for the Jews of China?

Zhang knew nothing about the subject before leaving Hong Kong’s Singapore International School and arriving in Britain five years ago. His journey to Kaifeng began in England, where he “fell in love with history”.

“I think in Hong Kong they don’t have as much of an emphasis on the humanities,” he says. “So when I came to the UK, I learned about the first world war and the second world war. The Holocaust was what got me into learning about Jews and the history of Judaism. Then that opened a gate into Chinese Judaism.”

The Kaifeng connection emerged as a result of some aimless internet surfing one evening, as the schoolboy bounced from one article to another. “I just fell down this rabbit hole,” he recalls, culminating in Zhang reading a piece on The New York Times’ website. “It talked about an ancient Jewish community …”

Jewish settlement in Kaifeng is thought to date back to AD600, when Persian merchants followed the Silk Road and then the Yellow River to one of the world’s most populated cities at the time. The earliest documentary evidence of Jewish presence is a business letter from the year 718, written in the Persian language but using Hebrew characters. In 1605, a Jesuit missionary was so struck by the area’s Jewish inhabitants that he sent a message about them to the Vatican.

The Jews of Kaifeng are not believed to have experienced any persecution or harassment, and proudly displayed official gifts they had received from emperors over the centuries. They managed to couple traditional Chinese customs, including foot binding and the taking of second wives, with Jewish practices, such as circumcision, abstaining from pork and observing the sabbath.

Their integration was so successful that, by the mid-19th century, generations of intermarriage with indigenous Han Chinese and the sinification of Jewish names had left the Jewish population virtually indistinguishable from their neighbours. By the time the synagogue, which faced Jerusalem, succumbed to flood damage, there was nobody left who knew enough Hebrew to read its Torah scrolls, which were sent to museums around the world.

One, bought by missionaries in 1851, was presented to the British Museum a year later. It comprised 94 strips of thick sheepskin sewn together with silk thread. Academics were excited to discover that despite centuries of isolation and assimilation, the contents of the Kaifeng Torahs were identical to conventional Hebrew scripture.

After the synagogue’s collapse, in about 1850, its timbers were sold to a local mosque and the land became a rubbish dump until the hospital that now stands on the site was built, in 1953.

Within five months of reading The New York Times article, the then 16-year-old Zhang embarked on a solo trip to Kaifeng, making the 12-hour train journey from Hong Kong in winter 2017. He had made contact with Guo Yan, whose Hebrew name is Esther, through WeChat. She is the curator of the Kaifeng Jewish History Memorial Centre, a private museum in her own home that tells the story of her ancestors.

The museum aside, there are a few traces of this ancient community, including a street named The Lane of the Sect that Teaches the Scriptures. Zhang spent a week in Kaifeng and received a personal tour from Guo.

“It’s incredible,” he says, “because her house is just filled with artefacts and paintings with Chinese and Hebrew – which you don’t really see – and there is also a huge painting of a synagogue, which looks more like an Asian temple from the outside, which I thought was wonderful.

“They are not really orthodox in the typical sense, but I find it incredible how the community has been able to retain that strong Jewish identity after so many years.”

DNA tests have confirmed Jewish lineage, but since the community has followed patrilineal descent, they are not considered Jews according to orthodox law, where identity is passed through the maternal line. Their strong sense of collective historical memory and respect for one’s ancestors, however, fit squarely into both Jewish and Confucian traditions.

Returning to school in Britain, Zhang made it his mission to share the heritage of the Kaifeng Jews with anyone who would listen. To that end, he established a comprehensive website, chinesejews.com. Its logo is a blue Star of David containing a red Chinese character for the Middle Kingdom, or China. “The gradual transition of colour [from blue to red] symbolises the impossibility of dividing the identity of the Chinese Jews, for they are neither Jewish nor Chinese, they are both,” Zhang explains.

He recruited ambassadors from among his fellow students at St Clare’s, in Oxford – young people from China, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, the Philippines and Russia – who have translated a summary of the history of Kaifeng Jews into their native languages and shared it online.

Last year, Zhang, who has a blog on The Times of Israel website, wrote and self-published a book, Jews in China: A History of Struggle, in which he examines four waves of immigration: the Kaifeng community; the Baghdadi Jews who moved to Shanghai after the first opium war; the Russian Jews who moved to Harbin for a better life and prospered by selling natural resources from northeast China to Europe; and the German and Austrian Jews who fled the Nazis and found sanctuary in Shanghai.

Written with guidance from members of the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, the book has found an audience that includes a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, in the United States, and London’s Wiener Library, the world’s oldest Holocaust archive, and is top of the “Further reading” list on Wikipedia’s “Kaifeng Jews” page.

Zhang accepts with good humour people’s puzzlement at what, in his own words, is “a fairly niche area of interest”. He has been on the receiving end of “a bit of banter” at school. “There have been times when people have thought it’s a bit nerdy,” he says.

He traces his interest back to a meeting in Hong Kong with Ronald Leopold, the executive director of the Anne Frank House, in Amsterdam, whom he interviewed as a junior reporter for the South China Morning Post’s Young Post . Leopold invited Zhang to visit him and the museum in the Netherlands, which deepened Zhang’s knowledge of Jewish history and, through a series of introductions, led to an internship at the Hong Kong Holocaust and Tolerance Centre.

Although Zhang was raised a Christian, there is a crucial Jewish element to his own family history. His Chinese great-grandmother, Chen Meiyue, was visiting Hong Kong in 1949 and found herself unable to return home to Shanghai in the wake of the communist revolution. It would be the start of three decades in exile.

She made her way to the US, speaking no English and with no money or paperwork, and spent years avoiding the authorities there. Eventually she found herself in the Catskill Mountains, in upstate New York, an area dubbed the “borscht belt”, named for the Eastern European beetroot soup.

In a stroke of luck, she ended up at the Concord Resort Hotel, where Jewish owner Robert Parker offered her a job as a maid and sponsored her to become an American citizen. And when China reopened to the West, Parker sponsored her five children, their spouses and her 10 grandchildren to come to the Catskills to work in housekeeping or in the resort’s kosher restaurant. Among them was Zhang’s mother, Lily.

“It is amazing, because one family sponsoring 20 Chinese immigrants is quite revolutionary,” says Zhang. “And so I grew up listening to stories of my mum burning the incense of Chinese New Year and burning the candles of Hanukkah.” She also passed on a handful of Hebrew greetings she learned as a girl and the dishes her Jewish hosts enjoyed during the festival of Passover.

“Some people assume I’m Jewish, some people ask if I’m Jewish,” says Zhang. Would he consider converting? “Actually, nobody’s ever asked me that. I don’t know. I think Judaism is absolutely wonderful. Obviously I’m not Jewish, but I feel part of this community so I want to continue in that sense.”

Zhang is not the only person sharing the story of the Jews on the banks of the Yellow River. After his presentation at Limmud, he makes a pilgrimage to Kaifeng, a kosher Chinese restaurant in Hendon, north London, which offers a potted history of the area on the back of its menus. And photographer John Offenbach’s exhibition, “JEW”, at the Jewish Museum London, includes two Kaifeng Jews among the 33 portraits “dispelling the myth that there is just one type of Jew”.

But groups trying to engage with Kaifeng Jews on the ground have been having difficulty of late. Judaism is not one of the five religions – Buddhism, Taoism, Catholicism, Protestantism and Islam – recognised by the Chinese state.

According to The Jerusalem Post, in the past two years, the community has come under strict surveillance. During one raid at a Jewish community centre, officials reportedly tore a metal Star of David and Hebrew texts from the walls and tossed them to the floor, and threw dirt and stones into a well used as the community’s mikveh, or ritual bath. “And all foreign plans to build up and support the Jews of Kaifeng were summarily cancelled,” reported the paper.

As President Xi began to consolidate his position on religions, the Kaifeng Jewish descendants found themselves swept up in the ‘unauthorised religions’ campaignAnson Laytner, president, Sino-Judaic Institute

This includes the work of Shavei Israel, an organisation that helps “lost” and “hidden” Jews around the world reconnect with Judaism and, if they wish, emigrate to Israel. The Kaifeng Jews are listed on its website as one of the eight communities it works with, along with the Inca Jews of Peru and Jews hidden in Poland as a result of the Holocaust. It has helped 20 Kaifeng Jews make aliyah (the move to Israel), but in 2014, police ordered Shavei Israel to close its community centre in the city. The US-based Sino-Judaic Institute, founded to promote the study of Jewish life in China and tourism to Kaifeng, was forced to pull out of the city in 2015. The clampdown has also banned Jews from congregating outside their homes.

“Currently we are in contact with some Kaifeng Jews, helping them keep their flame alive during this challenging period. Ideally, we’d like to see the Chinese government recognise this historic community, celebrate its longevity and permit the Kaifeng Jews to learn about and practise their Chinese Jewish culture.”

Zhang, however, insists he is not interested in the politics; he is simply gripped by a story of endurance, survival and “the beautiful coexistence of two ancient cultures”.

As he puts it, his “obsession” is studying and disseminating the engrossing history of a “long-forgotten civilisation at the crossroads of the Holy Land and the Middle Kingdom”.