A Fiendish Conversation with Jim Woodring

Jim Woodring wields his massive pen in his studio.

Image: Photo Courtesy Mark Woods

Ever a peddler of the surreal oddities of the mind, Seattle illustrator and creator of the Frank comics series Jim Woodring employed a larger-than-life artistic implement to create his new Frye Art Museum-commissioned exhibit, The Pig Went Down to the Harbor at Sunrise and Wept (January 21–April 16). The ten psychologically explorative and trippy black-and-white, framed images of abstract dreamscapes were inked by Woodring using his gigantic, five-foot-long handcrafted dip pen. Mightier than the sword indeed.

For our latest Fiendish Conversation, we chatted with Woodring about using the massive artistic implement, trying to achieve an abstract impressionist mindset, and pulling artistic order from chaotic noise.

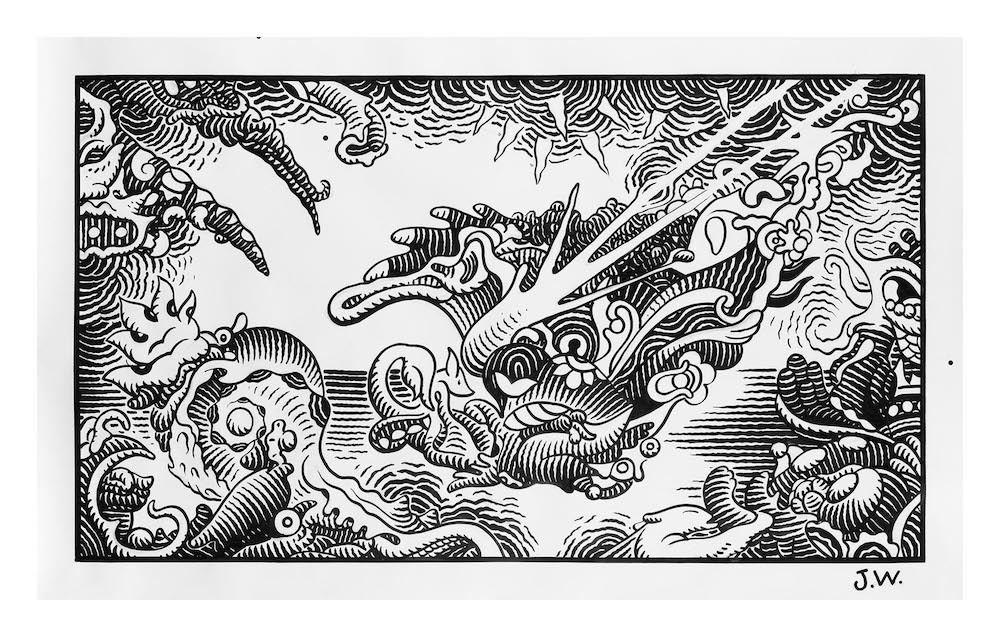

Jim Woodring, The Pig Went Down to the Harbor at Sunrise and Wept #2, 2016, acrylic ink on paper, 42 x 71 in.

Image: Courtesy Jim Woodring

What are your personal favorite aspects about The Pig Went Down to the Harbor at Sunrise?

It’s hard to pick out a favorite aspect, because it’s kind of a perfect storm of good things coming together— a confluence. The Frye gave me the opportunity to produce these drawings with the assurance that they would be displayed, and that was fantastic. I’ve never had an experience or opportunity like that come along.

And the doing of them was spectacular for me because it was the first time I’ve ever worked on that scale. I’ve always used the pen and ink, but always had a drawing board. I’ve always carefully worked out what I was going to do. When I made these pictures, I didn’t have the time to really overthink them. I just really went for shapes and effects and encounters and blowback, and all this different stuff that I imagine going on in them. And it was the first time I ever got close to experiencing what I imagine what the abstract expressionists and all those guys felt when they approached those big canvases with nothing in mind but an approach.

Is there anything that typical sparks your creative process and fires you up to dive into a new work?

It varies from project to project, depending on what it is I have to do. This was different from anything I’ve ever done, because it was more abstract and required the kind of thinking that I don’t ordinarily get to enjoy. My approach was simply to get a concept of a scenario, try to draw it symbolically, and then just try to refine it. It was just pure pleasure with no boundaries, no limits.

And [I was working with] the knowledge that when I finally had the drawing worked out, I was going to get to ink it with this pen, which was thing in itself for me. I’ve used a pen for 50 years. I’m in love with it. I’m intrigued by it. It’s an ongoing education. And seeing those huge pen lines with that characteristic… a pen line is different from a brush, because it’s really connected to you. With a brush, there’s kind of a flexible shaft that gives you this kind of prosthetic smoothness. The pen just records every movement you make. And it’s so exciting to watch those things flow out of this nib while I was trying to make these drawings come together. It was just an exhilarating thing.

How did that massive pen itself come about? What was the impetus for the creation of such an implement?

Well the impetus was that I was in London in the ‘90s at a famous store called Philip Poole and Company, and they sold nothing but pen points and pen related paraphernalia. And Mr. Poole was in his nineties at the time and he has some oversized pens that that had nibs that were 4 inches long. And I said “Gosh, do they make them any bigger than that?” And he said, “No, you couldn’t make a pen bigger than that. It just couldn’t work.” And I thought, well no Englishman is going to…

So I just got back and I had a relationship with this arts organization, United States Artists, and they had an early version of the kind of thing that became Kickstarter. And they said, hey we’ll raise some funds for you for a project, and so I designed this pen and had it made in Seattle with the money that they raised for me.

And then I spent a couple years, doing some demonstrations with it and showing how it worked. I tried to do some drawings of things like frogs and shrunken heads, but they were just big drawings. They looked, just like blown up ink drawings, they had that kind of novelty but there’s nothing else going on. There has to be a vocabulary for using this thing that expresses it to good advantage. And so that was what I sought after. I realized, well, the line does something; the way you get graze in an ordinary pen drawing by stacking them up, but in this case [with this pen] it’s just going to be banks of lines.

I took a month off from working on these pantomime cartoon books; just devoted myself to working on these drawings. Then when I had a couple of them I rolled them up and took them to the Frye and showed them to Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker because she was leaving, and she offered me a show on the spot.

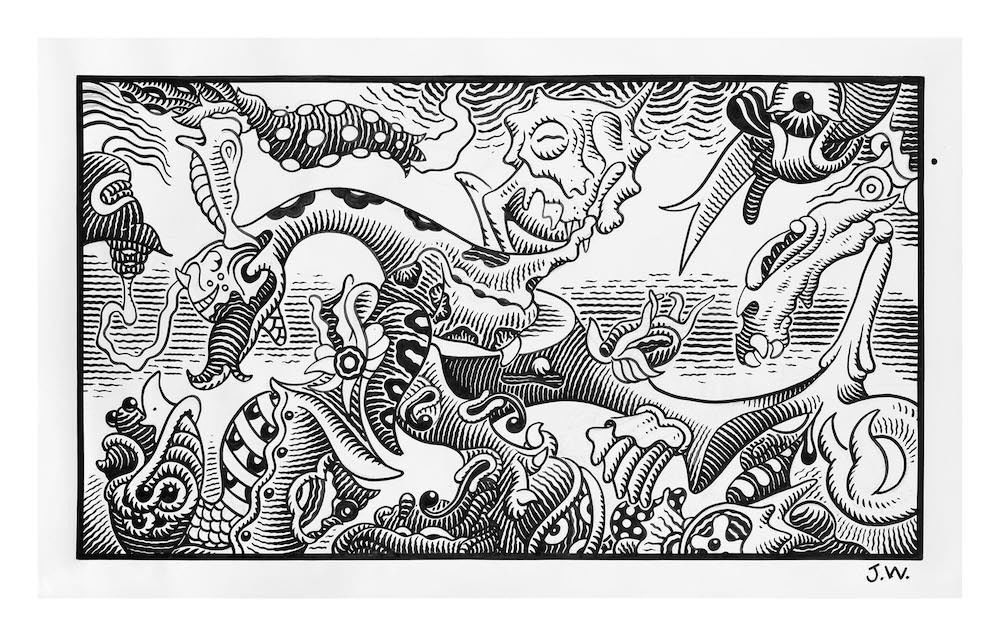

Jim Woodring, The Pig Went Down to the Harbor at Sunrise and Wept #4, 2016, acrylic ink on paper, 42 x 71 in.

Image: Courtesy Jim Woodring

What are your favorite aspects about using the pen and what are some of the challenges or frustrations it presents?

What I like most about it is what I like about the pen in general, and that is that it’s an ancient technology and everybody who’s ever used one has faced the same kind of difficulties with it. I like to look at old pen and ink drawings, because I can see where they got tired or where they had trouble making this kind of loop or whatever—things that I can relate to. And I would like to think that those guys would see this giant pen and go, “Oh wow, can I try that?”

Learning to use a pen was frustrating, but it was so profoundly enjoyable to master this thing by which I knew I would eventually be able to express myself. And a similar thing happened with this [large pen], it took me a long time to learn how to use it so it didn’t drip, how to control it, how to manage it, how to stand… it just took a long time to figure it out. And now there’s questions of stamina and all the rest of the other things you have to master in order to get consistency. It’s like I’m 26 again learning to do this new thing. So that’s great.

How long did it take to create one of the works in the show?

From just starting to work in a sketchbook to finished picture, it’s about two and a half weeks for each. Because I do a lot of preliminary drawings for each one. With quite a few of them, I got down a road and I thought: oh, this is too dense or this hangs it up or this isn’t flowing or this has got to be connected because its relationship is important or whatever. So I would just abandon it and do it over.

You mentioned the abstract expressionists and your drawings certainly can get surreal. What do you think we can learn about our concrete reality thorough art that’s surreal and abstract?

I don’t know how they would augment your view of reality and concreteness, but I think that they might sort of lubricate your mind. It seems to me that modern art—once it stopped being pictures of kings and horses and landscapes and that kind of thing—is like a game. When you walk into a modern art gallery, you’re there to either like it or dislike it, to engage it or disengage, but you want your mind to play a certain variety of a wide spectrum of games with whatever it is you’re looking at.

I guess you get out of a painting what goes into it. So if there’s some guy that’s so successful maybe he’s obliged to knock out pictures quickly and he doesn’t put as much juice in each one as he was when he was really doing it, that comes out of the picture. You perceive it. [You can tell] when anybody’s really working hard: throwing away ideas, refining it, saying this can be closer. Looking at everything: negative space, movement… When I was in high school I read Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook and those principles stayed with me—although I might be misremembering them.

Thinking about the language that the abstract expressionists developed to express these arcane things, you saw other people trying to do something similar—express the ineffable with a personal vocabulary in a way that makes it universal. That’s this game that I was playing with these drawings: do it, refine it, change it until it’s as good as you can get it. I did a couple of them over because they didn’t come as close as I wanted to being the best I could do.

What other artistic projects are on your horizon?

Well I’m finishing up a 100 page graphic novel. I’m also redesigning re-issues of a couple of my other books. Then I’m putting together a larger book compilation of additional stuff… it’s hard to describe. And then I want to do some classical cartooning projects.

It just seems like this is a great time to pull order out of chaos and make something happen. There’s an awful lot of red noise and gray noise and shit in the air, and it seems like it’s a good time to start making sense of things.

Jim Woodring: The Pig Went Down to the Harbor at Sunrise and Wept

Jan 21–Apr 16, Frye Art Museum, Free

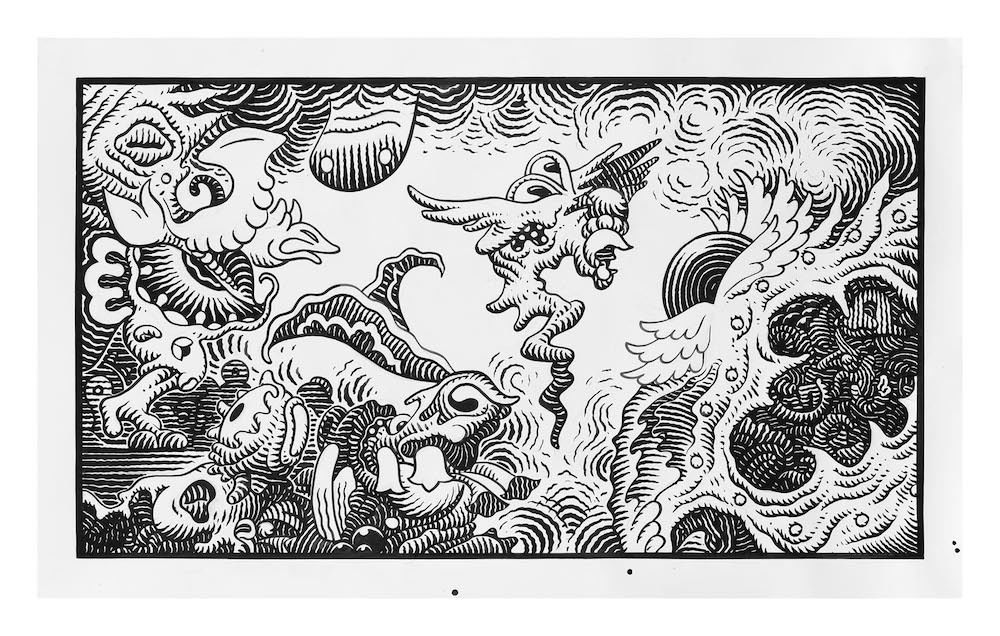

Jim Woodring, The Pig Went Down to the Harbor at Sunrise and Wept #3, 2016, acrylic ink on paper, 42 x 71 in.

Image: Courtesy Jim Woodring