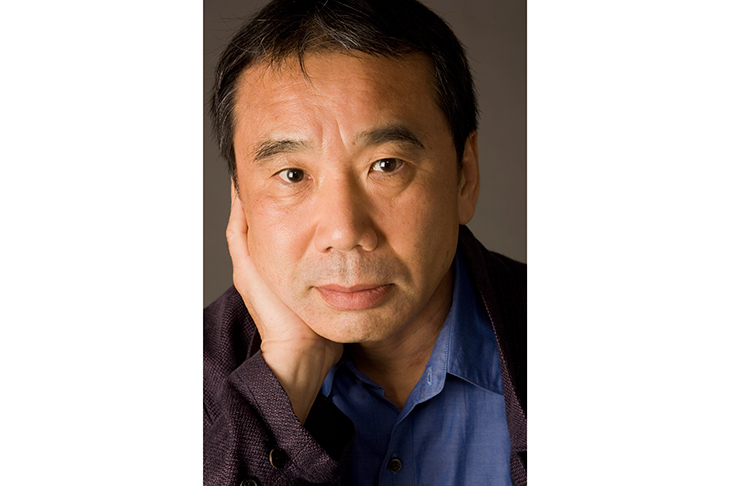

Haruki Murakami’s Killing Commendatore was published in Japan in February last year. Early press releases for this English version hailed the book as ‘a tour de force of love and loneliness, war and art — as well as a loving homage to The Great Gatsby’. Anyone familiar with Murakami’s 17 preceding novels can vouch for love and loneliness as his great themes; and war, art and F. Scott Fitzgerald are not new to him, but in Commendatore all enrapture.

The narrator, a man with no name struggling with his own art — and, concurrently and inseparably, the women he sleeps with — recalls Murakami’s earlier nameless narrators, all the way back to Hear the Wind Sing (1979). A damaged, constant observer, he is also something of a Nick Carraway, while his neighbour across a rural mountain valley, the mysterious, wealthy Mr Menshiki in his shining solitary mansion, recalls Jay Gatsby.

The name Menshiki means colourlessness or the avoidance of colour, and from his house to his hair he is daisy-white. He has moved to this remote place because of a woman and a girl. Yet ‘loving homage’ in no way means a one-on-one correspondence. Neither longtime inspirations nor his own imagination fail Murakami here; Commendatore is a perfect balance of tradition and individual talent.

As well as Fitzgerald, William Faulkner is a guiding presence here, along with a host of other predecessors. The landscape in Commendatore is a Japanese Yoknapatawpha, where past and present, interior and exterior consciousness, and art and life in a recreational game with each other are the setting, the characters and the plot.

Murakami’s narrator, a successful but disaffected portraitist, realises as his marriage falters that he wants his art to show not smiling public faces but the skull, and the soul, beneath the skin. The ancient rural cottage he is borrowing belongs to a celebrated painter, Tomohiko Amada, who studied European painting in Vienna in the 1930s, fell in love with a woman who was later killed by the Nazis and escaped just in time to Japan.

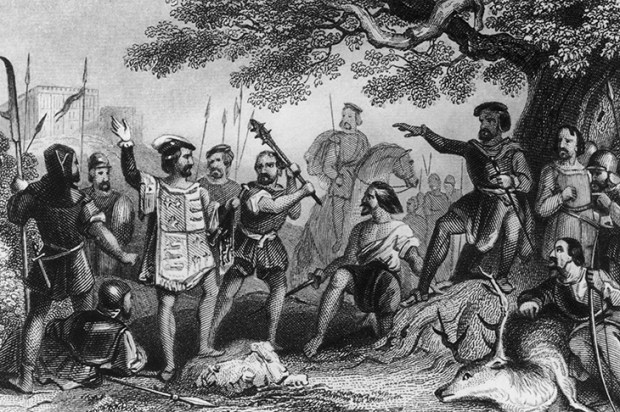

After the war, he re-emerged, adopting an ancient Japanese technique and style. Now 92 and fading into lifelessness, Amada has been moved to a posh Tokyo care home, but something of his spirit remains in his old house and studio, along with one hidden painting that tells a tremendous story. This painting, ‘Killing Commendatore’, shows that scene from Don Giovanni, and it also lets the narrator, and us, imagine what befell Amada and his loved ones during the second world war.

Murakami has always loved writing about other arts, and particularly music. Killing Commendatore has opera as its principal soundtrack, though increasingly Bruce Springsteen’s The River album joins in. Other sounds — the natural music of a rustling, hooting night owl, the subterranean knell of a long-buried bell — help compose a novel that rings in one’s ears as surely as does Gatsby, with its yellow cocktail music, Klipspringer’s piano playing, and those ‘muffled and suffocating chords’ that fight their way up from the Plaza ballroom.

Amidst such sensory stimulation, it’s no wonder Murakami’s painter prefers to paint from photographs; it’s easier than using a life model and far safer than using one’s own clouded and fearful memories. When he relents, and begins to paint Menshiki from life, a rupture ensues between real and imagined. Which is the real world, anyway, in artistic terms? Murakami’s artist relates the act of painting to the literal illumination of ideas. To ‘discover this painting’, as he puts it, is the task of beginning to create.

Nothing is painted there yet, but it’s more than a simple blank space. Hidden on that white canvas is what must eventually emerge. As I look more closely, I discover various possibilities, which congeal into a perfect clue as to how to proceed. That’s the moment I really enjoy. The moment when existence and nonexistence coalesce.

Murakami dancing along ‘the inky blackness of the Path of Metaphor’ is like Fred Astaire dancing across a floor, then up the walls and onto the ceiling. No other writer so commands that manner of storytelling wrought from a stream of rich ideas, the thought-river, the word-hoard long used and newly brought to life, flowing ‘along the interstice between presence and absence’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in