Emily Kam Kngwarray painting Earth's Creation I in the Utopia region, Central Australia, 1994

Photo © reserved

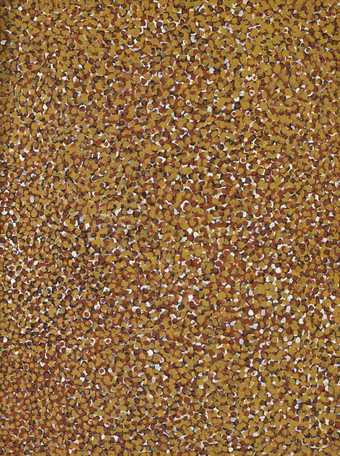

Emily Kam Kngwarray (1910–1996) was in her late 70s when she was introduced to acrylic paint and began painting in earnest. For the next eight years until her death she painted over 3,000 canvases – roughly one painting per day. Her work erupted into the art market in the late 1980s with huge success, aiding in raising global awareness of contemporary Australian indigenous art, which the art critic Robert Hughes hailed as ‘the last great art movement of the 20th century’.

Over the past 30 years, Kngwarray’s art has been considered in terms of both Western abstract art and Eastern aesthetics. Some have compared her work stylistically to artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko. The layering of repeated dots across lines of colour in the painting Untitled 1990 in Tate’s collection, for example, seemingly resonates with the technical and colouristic approaches of these abstract expressionists. Her 2008 solo exhibition Utopia: The Genius of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, meanwhile, broke records for audience numbers in Japan – surpassing the previous record-holder, an Andy Warhol exhibition held over ten years previously – and inspired comparisons between her work and Eastern calligraphy. Anwerlarr anganenty (Big yam Dreaming) 1995, for instance, with its thick white lines against a bold black background, seemingly inverts the visual language of Japanese calligraphy.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Untitled

(1990)

Tate

© Estate of Emily Kame Kngwarreye / DACS 2024, All rights reserved

These conceptual and aesthetic approaches, however, belie some of the fundamental complexities of how uninitiated people grapple with Kngwarray’s art, since its meaning will forever be elusive to those outside her culture. Kngwarray belonged to the Anmatyerre people, one of the 500 different language groups of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander nations. As an Anmatyerre elder, Kngwarray was a custodian of women’s Dreaming sites in Alhalkere in the Utopia region, which is about 250 kilometres north of Uluru in the centre of Australia. Her painting practice was the artistic expression of this role, containing stories that only those who have been initiated through Anmatyerre ceremony can know.

For non-indigenous people, we might understand the Dreaming as the story of the interrelationship between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestral spirits, people, animals, plants and the land. Each person and his or her life is part of the Dreaming. It is not based on a chronology but is continuous and ever-present – being created now and incorporating the future. First Nation Australians have described this unique concept of time as ‘Everywhen’. The Dreaming is told through language, art, ceremony and songs and speaks to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders’ history, which reaches back at least 65,000 years. These are the longest-living continuous cultures in the world and the Dreaming carries the stories of these cultures.

Kngwarray’s painting developed through the ceremonial communication of the Dreaming. Her style is drawn from the body markings used in the Anmatyerre women’s ceremony called Awelye. During Awelye, Anmatyerre women paint Dreaming designs on their chests and shoulders using ground ochre, charcoal and ash – directly applying country to their bodies. As they paint these designs, they chant their Dreaming, which can last for hours, culminating in a final dance and chant. During the late 1970s, Anmatyerre women performed Awelye to demonstrate their ownership of territories, stories and Dreamings, which played a critical role in reclaiming their rights to the land.

Following the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976, Kngwarray and the Anmatyerre community returned to their ancestral homelands and continued to live according to the laws and customs of the clan. The following year, Kngwarray and other artists formed the Utopia Women’s Batik Group, whose members developed techniques to reimagine Awelye body painting into batik decoration on silk. Kngwarray continued to paint Awelye designs after she and the other Utopian artists started using acrylic paint on canvas in the late 1980s, as exemplified by Untitled (Alhalkere) 1989. The marks that form the characteristic ‘dots within dots’ style in the painting represent seeds found in Alhalkere, the colours reflect seasonal changes, while the patterns contain stories hidden from the uninitiated. Kngwarray painted Untitled (Alhalkere) on stretched canvas laid flat on the ground, sitting on the earth alongside her kin. She rarely left the land of which she was a custodian until her death in 1996.

Emily Kam Kngwarray

Anwerlarr anganenty (Big yam Dreaming) 1995

Acrylic paint on canvas

© Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency. Licensed by DACS 2020. Courtesy National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Undoubtedly, artistic developments of the 20th century, including modernism, have been crucial in how global audiences have approached Kngwarray’s work. While it remains a deeply problematic continuation of Western cultural domination in Australia, modernism offers one stylistic lens through which to appreciate Kngwarray’s work. Meanwhile, postmodernism’s assertion of multiple worldviews allows the possibility of appreciating Kngwarray’s work in a way that acknowledges diverse cultural references. It is within this context that her work was included in Okwui Enwezor’s 56th Venice Biennale in 2015 and also appears in the collection of the late American artist Sol LeWitt – a testament to the global reach of her influence, as well as the growing knowledge, awareness and appreciation of Kngwarray’s fierce assertion of her culture.

Emily Kam Kngwarray’s Untitled (Alhalkere) 1989, Endunga 1990 and Untitled 1990 were purchased with funds provided by Lady Sarah Atcherley in honour of Simon Mordant in 2019 and are on display as part of A Year in Art: Australia 1992, Tate Modern, from 15 February.