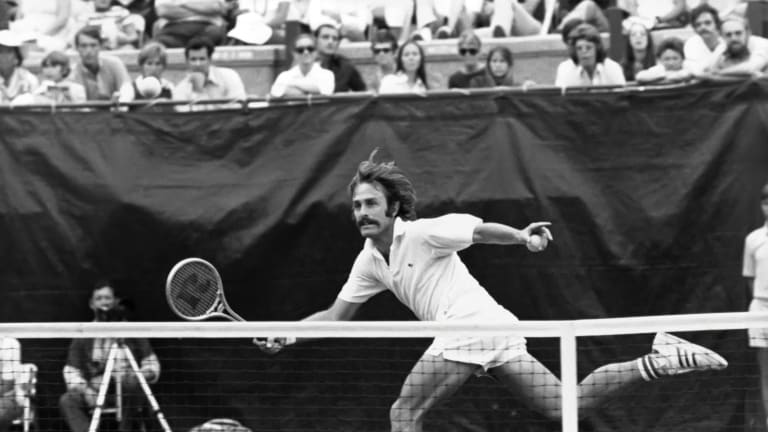

NEW BRAUNFELS, Texas—Here is John Newcombe, the lion in winter. The 26-time Grand Slam champion will turn 80 next year. He continues to boast the iconic moustache he grew just over half a century ago—the moustache that became a logo, and grew into what contemporary parlance calls a brand.

Variations of the moustache adorn Newcombe’s tennis ranch, a 31-court facility located a 30-minute drive northeast of San Antonio. The John Newcombe Tennis Ranch is both an academy for juniors and a lively getaway spot for adults.

On a late winter morning, Newcombe is at the ranch, about to commence a once-a-year event: Tennis Fantasies for Men and Women. Like just about every Australian tennis player, Newcombe has tremendous command of doubles. Nineteen of his majors came in men’s and mixed.

But of the seven singles Slam titles Newcombe earned—two Australian Open, three Wimbledon, two US Open—none was more redemptive than the one he won 50 years ago in New York.