Apple's Marketing Playbook Was Written in the 1920s

Former General Motors CEO Alfred Sloan's two marketing principles -- "a car for every purse or purpose" and "dynamic obsolescence" -- have helped make the iPod, iPhone, and iPad possible

It was the most advanced consumer product of the century.

The industry started with its innovators located in different cities over a wide region. But within 20 years it would be concentrated in a single entrepreneurial start-up cluster. At first it was a craft business, then it was driven by relentless technology innovation and then a price war as economies of scale drove efficiencies in production. When the market was finally saturated the industry reinvented itself again - one company discovered how to turn commodity products into "needs." They opened retail outlets across the country and figured out how to convince consumers to flock to buy the newest "gotta have it" version and abandon the perfectly functional last year's model.

No, it's not Apple and the iPhone. It was General Motors and the auto industry.

IN THE BEGINNING

At the beginning of the 20th century the auto industry was still a small hand-crafted manufacturing business. Cars were assembled from outsourced components by crews of skilled mechanics and unskilled helpers. They were sold at high prices and profits through nonexclusive distributors for cash on delivery. But by 1901, Ransom Olds invented the basic concept of the assembly line and in the next decade was quickly followed by other innovators who opened large scale manufacturing plants in Detroit - Henry Packard, Henry Leland's Cadillac, and Henry Ford with the Model A.

The Detroit area quickly became the place to be if you were making cars, parts for cars, or were a skilled machinist. By 1913 Ford's first conveyor belt-driven moving assembly line and standardized interchangeable parts forever cemented Detroit as the home of 20th century auto manufacturing.

The automobile industry was founded and run by technologists: Henry Ford, James Packard, Charles Kettering, Henry Leland, the Dodge Brothers, Ransom Olds. The first twenty-five years of the century were a blur of technology innovation -- moving assembly line, steel bodies, quick dry paint, electric starters, etc. These men built a product that solved a problem - private transportation first for the elite, and then (Ford's inspiration) -- transportation for the masses.

Ford tried to escape the never-ending technology feature wars by becoming the low cost-manufacturer. Fords River Rouge manufacturing complex - 93 buildings in a 1 by 1.5 mile manufacturing complex, with 100,000 workers - vertically integrated and optimized mass production.

By 1923, through a series of continuous process improvements, Ford had used the cost advantages of economies of scale to drive down the price of the Model T automobile to $290.

When the 1920's began there were close to a 100 car manufacturers, but the relentless drive for low cost production forced most of them out of business as they lacked capital to scale. For a brief moment, half the cars in the world were now Fords. To make matters worse, the long service life of Ford and GM cars (8 years for Fords Model T, 6 years for everyone else) retarded sales of new cars. In 20 years, U.S. car ownership had risen from 0 to 80% of American families - the market was approaching saturation.

Now cars would have to be sold almost entirely to people who already owned a car.

THE CRAZY ENTREPRENEUR

After success as a leading manufacturer of horse-drawn carriages, Billy Durant was one of the few who saw the writing on the wall and got into the car business. Although he wasn't a technologist, he was an entrepreneur with a great eye for acquiring car companies run by technologists. His keen insight was that several carmakers combined under one company umbrella would have more growth potential than one brand on its own. Like most founders, he was great at searching for a business model but terrible at in large company execution. When his board fired him, Durant bought a competing company called Chevrolet, built it larger than his last company, and used Chevy stock to buy out his old company - General Motors - and threw out the board. Yet a few years later under his brilliant but reckless leadership GM was again on the brink of financial disaster and his new board fired him. (Durant would die penniless managing a bowling alley.)

Durant's ultimate replacement - an accountant named Alfred P. Sloan - would turn GM into the leading and most admired company in the U.S.

Over the next decade Sloan would implement a series of innovations which would last for over half a century and catapult General Motors from the number 2 car company (with a ¼ of Ford's sales) into the market leader for the next 100 years. Here's what he did:

-- Distributed Accounting Unlike Ford, GM was originally a collection of separate companies. Distributed Accounting turned those fiefdoms into product divisions each of which, could be focused like Ford's mass-produced lines. But Sloan went further. He figured out how to centralize financial oversight of decentralized product lines. His CFO created standardized division sales reports and flexible accounting, and allocated resources and bonuses to the GM divisions by a uniform set of rules. It allowed GM to be ruthlessly efficient internally as well with its dealers and suppliers. It got the division general managers to fall in line with corporate goals but allowed them to run their divisions freely. GM became the prototype of the modern multi-divisional company.

-- Car Financing. Realizing that Ford would only accept cash for car purchases, in 1919 GM formed GMAC to provide new car buyers a way to finance their purchases through debt.

-- Consumer Research. Every since his days at Hyatt Roller Bearing, Sloan, and by extension GM, was relentless about getting out of the building - they had an entire department that studied consumers, dealers, suppliers. More importantly, Sloan led by example. He visited dealers and suppliers, listened to customers and was tied tightly to his head of R&D Charles Kettering.

All this would have made General Motors a well-run and well-managed company. But what they did next would make them the dominant company in the U.S. and eventually put tail-fins on the iPhone.

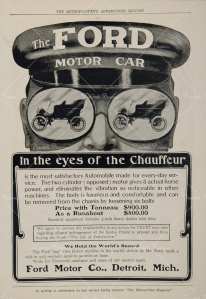

By the early 1920's General Motors realized that Ford, which was now selling the Model T for $290, had an unbeatable monopoly on low-cost automobile manufacturing. Other manufacturers had experimented with selling cars based on an image and brand. (The most notable was an ad by the Jordan Car company.) But General Motors was about to take consumer marketing of cars to an entirely new level.

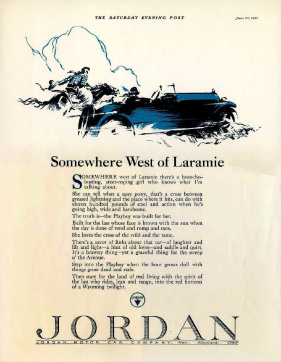

General Motors had turned the independent car companies acquired by its founder Billy Durant into product divisions. But in a stroke of genius GM transformed these divisions into a weapon that Ford couldn't match. With the rallying cry "a car for every purse and purpose," GM positioned its car divisions (Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac) so they would cover five price segments -- from low-price to luxury. It targeted each of its brands (and models inside those brands) to a distinct economic segment of the population. Chevy was directly aimed at Ford -- the volume car for the working masses. Pontiac came next, then Oldsmobile, then Buick. The top-of- the-line Cadillac offered luxury and prestige announcing you had finally arrived at the top of the conspicuous consumption heap. Consumers could announce that their status had improved by upgrading their brands.

GM had one more trick to make this happen. Within each brand, the top of the line was just a bit less expensive than the lowest priced model of the next expensive brand. The goal was to convince the consumer to spend that little bit more to trade up to a more prestigious brand.

Market segmentation by price was something no other automotive manufacturer had ever done. While other car companies could compete with one of GM's divisions, few had GM's capital and resources to compete simultaneously with the onslaught of car models from all five divisions.

GENIUS STROKE II: "DYNAMIC OBSOLESCENCE"

While market segmentation allowed GM to use its divisions to reach a wider market than Ford or Chrysler, this didn't solve the problem of market saturation. By the late 1920's, most everyone in the U.S. had a car. And cars lasted 6 to 8 years. Even worse, the market was now filled with used cars that provided even lower cost basic transportation. Sloan, the General Motors CEO, faced two seemingly unsolvable challenges:

1) How do you get consumers to abandon their perfectly fine cars and buy a new one?

2) How do you turn a product that competed on price and features into a need?

In another stroke of genius, GM invented the annual model change. Sloan borrowed this idea from fashion where styles changed every year and applied it to automobiles starting in the 1920s. General Motors would change the external appearance of cars every year. Sloan preferred to call it "dynamic obsolescence."

Styling and design became an integral part of GM's strategy. Sloan hired Harley Earl to set up GM's in-house styling staff. Earl would run it from 1927 to 1958.

Before Earl, cars were designed by in-house body-engineers who focused on practical issues like function, costs, features, etc. Each exterior component was designed separately to be functional - radiator, bumpers, hood, passenger compartment, etc. Some companies used 3rd party bodymakers to set the style, but GM was the first to take car design away from the engineers and give it to the stylists.

The concept of yearly "improvements", whether styling or incremental technology improvements, every model year gave GM an unbeatable edge in the market. (Henry Ford hated the idea. He had built Ford on economies of scale. The Ford Model T lasted for 19 years.) Smaller car makers could not afford the constant engineering and styling changes they had to make to keep competitive. GM would shut down all their manufacturing plants for a few months and literally rip out the tooling, jigs and dies in every plant and replace them with the equipment needed to make the next year's model.

GM had figured out how to take a product which solved a problem -- cheap transportation -- and transform it into a need. It was marketing magic that wasn't to be equaled until the next century.

By the mid-1950′s every other car company was struggling to keep up.

Starting in the 1920's and continuing for the next half century, automobile advertising hit its stride. Ads emphasized brand identification and appealed to consumers' hunger for prestige and status. Advertising agencies created catchy slogans and jingles, and celebrities endorsed their favorite brands. General Motors turned market segmentation and the annual model year changeovers into national events. As the press speculated about new features, the company's added to the mystique by guarding the new designs with military secrecy. Consumers counted the days until the new models were "unveiled" at their dealers.

For fifty years, until the Japanese imports of the 1970's, Americans talked about the brand and model year of your car - was it a '58 Chevy, '65 Mustang, or 58 Eldorado? Each had its particular cachet, status and admirers. People had heated arguments about who made the best brand.

The car had become part of your personal identity while it became a symbol of 20th Century America.

After Sloan took over General Motors its share of U.S cars sold skyrocketed from 12 per cent in 1920, until it passed Ford in 1930, and when Sloan retired as GM's CEO in 1956 half the cars sold in the U.S. were made by GM. It would keep that 50% share for another 10 years. (Today GM's share of cars total sold in the U.S. has declined to 19%.)

HOW THE IPHONE GOT TAIL FINS

Over the last five years Apple has adopted the GM playbook from the 1920′s: take a product, which originally solved a problem -- cheap communication -- and turn it into a need.

In doing so, Apple did to Nokia and RIM what General Motors did to Ford. In both cases, innovation in marketing completely negated these firms' strengths in reducing costs. The iPhone transformed the cell phone from a device for cheap communication into a touchstone about the user's image. Just like cars in the 20th century, the iPhone connected with its customers emotionally and viscerally as it became a symbol of who you are.

The desire to line up to buy the newest iPhone when your old one works just fine was just one more part of Steve Jobs' genius. It's how the iPhone got tail fins.

It's one more reason why Steve Jobs will be remembered as the 21st century version of Alfred P. Sloan.

This article also appeared on SteveBlank.com, a partner site.