Andrea Dworkin was never my kind of feminist. I grew up in the ’90s and embraced my sexual freedom, while Dworkin’s stance was dogmatic about wanting to ban porn and sex work. When I learned about the Second Wave I disavowed her as a man-hating killjoy and stayed loyal to sexual liberationists like my mother, feminist writer and activist Ellen Willis, who thought the pursuit of happiness and pleasure was key to feminism since the early days of the women’s movement, and was diametrically opposed to Dworkin’s dark absolutism in the 1980s. I parroted the (false) assertion that Dworkin thought “all sex was rape.” I’d also absorbed the misogyny lobbed at her, because photos of her repulsed me: fat, dowdy, unsmiling. No, Andrea Dworkin was not for me.

The only problem was, until very recently, I’d never read any of her work.

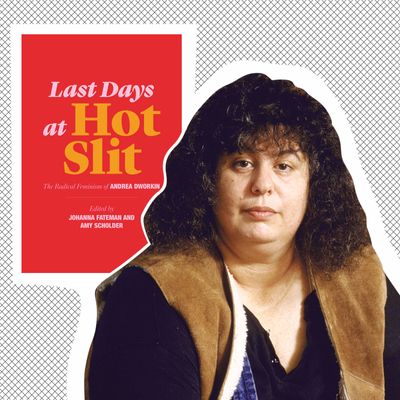

Reading Last Days at Hot Slit, a new collection of Dworkin’s work edited by Amy Scholder and Johanna Fateman, was the first time I truly confronted her most infamous writing — from books like Woman Hating, Intercourse, and Pornography: Men Possessing Women, along with lesser-known memoir, fiction, and speeches. After years of dismissing the angry, incendiary texts that I felt gave feminism a bad rap, I girded myself for an intellectual assault. My appreciative reaction surprised me.

The collection contains Dworkin’s more outrageous assertions, the ones that repelled me as a young woman and concerned critics like my mom and other pro-sex feminists fighting for women’s desires to be acknowledged and accepted — that men need to forgo their “precious erections” and “make love as women do together.” That pornography “incarnates male supremacy” and is “the DNA of male dominance.” That all intercourse, while not literally rape, violates the integrity of a woman’s body, that women who want it are “experiencing pleasure in their own inferiority.” What women really want, she argues, is “a more diffuse and tender sexuality.” (Speak for yourself!) Her lens was dark as hell: “We are very close to death,” she said in a speech about rape. “All women are.”

But I also discovered that the way she shared intimate, sometimes shocking details of her sexual and romantic life — rife with domestic abuse, molestation, and rape — came off as brave and poignant. I was touched by her love for her father and her gay husband, John Stoltenberg. I was also impressed with her prescience: “Shitty Media Men!” I wrote in the margins of a speech about sexual assault, wherein she plainly stated, “We must make the identities of rapists known to other women.” The excerpt of her 1983 book, Right-Wing Women, on conservative wives’ cynical calculus of supporting male supremacy as a way to harness their own power, felt like a direct comment on the sizeable percentage of white women who voted for Donald Trump, and the rise of Sarah Palin before that.

In many ways, my views about feminism were shaped by the disagreement about the role of sex in women’s liberation, which morphed into the “sex wars” of the late 1970s and 1980s — the “anti-sex” feminists on one side, the “pro-sex” feminists on the other. I wouldn’t call Dworkin’s diatribes “anti-sex,” exactly — she described it often in lush, filthy-mouthed detail — but they were deflating to many feminists at the time. When my mother reviewed Pornography: Men Possessing Women in the New York Times in 1981, she found the book’s “relentless outrage” to be “less inspiring than numbing, less a call to arms than a counsel of despair.”

I grew up in a context in which the pro-sex side had won, so to me, Dworkin’s conclusions about porn and sex still felt narrow and joyless. Yet I wasn’t alarmed so much as emotionally kickstarted by her urgency. The logical conclusions of Dworkin’s work have not come to pass; as co-editor Johanna Fateman told Michelle Goldberg in the New York Times recently, “You don’t have to be afraid that Andrea Dworkin is going to take your pornography away.” We live in a world in which most women feel entitled to sexual and political power, as the pro-sex feminists hoped. We understand the need for a world that condemns male domination while also taking female sexuality seriously — and still a harmonious blend of those two things eludes us. That’s why the predation of powerful men, the slut-shaming of their victims, and the avalanche of abortion restrictions in a largely pro-choice nation make us more pissed off than ever.

With the right to sexual pleasure safely a tenet of modern feminism, her writing serves a different function for me: It galvanizes me to dispense with likeability and embrace indignation. I thought back to what my mom had written about a misogynistic Sex Pistols song in 1977: “Music that boldly and aggressively laid out what the singer wanted, loved, hated challenged me to do the same” — so even as she vehemently disagreed with the content, “the form encouraged my struggle for liberation.”

Andrea Dworkin is my Sex Pistols for the #MeToo era. Next to the vacant, rah-rah version of sex positivity I grew up with in the ’90s, Dworkin’s rage seems downright clear-eyed — even if she might have called cheerful teenage sluts like me “left-wing whores” and “collectivized cunts” for imitating male models of sexuality. A foe of nuance, Dworkin nevertheless invites us to complicate our unbridled enthusiasm for sex. Last Days at Hot Slit is a mirror for what I’ve been afraid of for years: being defiant, being ugly, being unloved by men, even being unloved by other feminists like Andrea Dworkin. “Women discovered each other,” she wrote in 1974 of the early women’s movement, “for truly no oppressed group had ever been so divided and conquered.” That’s a truth worth staring in the face.