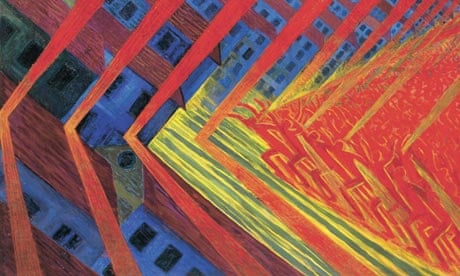

A full century lies between us and the founding of futurism, the first 20th-century movement to deal head-on with the urgency of modernity. Futurism celebrated technology, the modern electrified city, the speed of cars and trains and planes: the pulse of urban life itself. Most important of all, it heralded the emergence of a new man (women didn't get a look-in), reconstructed in the light of the increasingly industrialised societies of the western world.

But Tate Modern's new futurism show, which has travelled from Paris and Rome, feels staid and dull, flat and sluggish. Many of the best works have not made the journey; perhaps the prospect of crossing the channel was too much for them. Umberto Boccioni's two versions of his 1911 tryptich States of Mind grapple with the emotions of people at a railway station – those who go, those who stay, the platform farewells – while Carlo Carrà's Milan Station, painted a year earlier, looks like a mouth full of girders, a gigantic maw; which, I guess, is what entering that sooty station might have felt like to a traveller. How quaint and naive so much futurism looks now.

As it is, the best things in the show aren't truly futurist at all, and are by Picasso, Braque, Gaudier-Brzeska and Malevich – whose 1914 Aviator seems inexplicably to be clutching a ghostly white sturgeon. Looking at Boccioni's 1912 Horizontal Construction, we find a dreary conventional portrait of the artist's mother, seated on a balcony, riven by cubistic fault lines and fissures. Boccioni's sculptures are much better, weirder, less reducible; though even his development of a Bottle in Space, good though it is, is borrowed from a cubist painting by Picasso.

The futurists often got lost in cubism. They recognised it had an amazing charge, but couldn't invent anything radical with it for themselves. For all their talk, their proclamations, their manifestos and their cookbooks, their megaphones and anarchic bombast, they did not spearhead a new beginning. They talked of doubling the power of their sight, and wanted to infuse their paintings with the power of x-rays. Now we can see right through them.

None of the key figures in the movement – Giacomo Balla, Luigi Russolo, Boccioni, Carra and Severini – were artists of the first rank. For all their grappling with a brave new world, they produced few truly memorable images, let alone any great paintings. Maybe we should see futurism as a transitional movement, overtaken by the first mechanised world war. In Italy, its concepts of modernity were later co-opted by Italian fascism. In Britain, it found a bellicose champion and rival in Wyndham Lewis and his vorticist movement – futurism for a small island. The young David Bomberg made wonderfully individual, quasi-abstract paintings while following futurism's heady example, but even he turned to a kind of expressionistic figuration that it pains me to look at almost as much as futurism itself.

I came to this exhibition expecting a more vibrant sense of the period, and much more supporting material – futurism was as much about talk, literary bombshells and self-promotion as it was about painting. I came away wanting more of the flavour of the period – more photographs, maybe even some film or crackly audio recordings, more hysteria. The catalogue is dense, but much of it almost unreadable. I can't tell if it's the fault of the original writers or their translators, or the ways they have approached their subject.

And what of futurism's legacy, particularly in Italy, and the way that Italian futurism and the modern movement influenced architecture and official culture under Mussolini? Of all this, there is only silence. Where's the clamour, the noise and vitality; why is the modern not more of an onslaught on the senses? This feels a curiously old-fashioned and academic show. The subject is ripe for an altogether different sort of reappraisal.