In death, the man who at his peak claimed to be the world's most successful living artist perhaps achieved the sort of art-world excess he craved.

On Tuesday, the coroner's office in Santa Clara, California, announced that the death of Thomas Kinkade, the Painter of Light™, purveyor of kitsch prints to the masses, was caused by an accidental overdose of alcohol and Valium. For good measure, a legal scrap has emerged between Kinkade's ex-wife (and trustee of his estate) and his girlfriend.

Who could have imagined that behind so many contented visions of peace, harmony and nauseating goodness lay just another story of deception, disappointment and depravity, fuelled by those ever-ready stooges, Valium and alcohol?

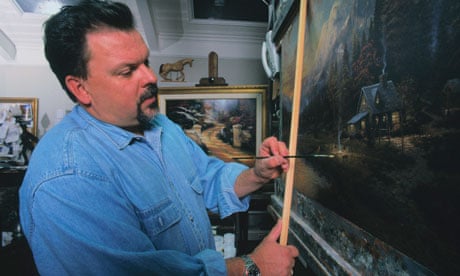

Kinkade was a self-made phenomenon, with his prints (according to his company) hanging in one in 20 American homes. At his height, in 2001, Kinkade generated $130m (£81m) in sales. Kinkade's twee paintings of cod-traditional cottages, lighthouses, gardens, gazebos and gates sold by the million through a network of Thomas Kinkade galleries, owned by his company, and through a parallel franchise operation. At their peak (between 1995 and 2005) there were 350 Kinkade franchises across the US, with the bulk in his home state of California. You would see them in roadside malls in small towns, twinkly lights adorning the windows, and in bright shopping centres, sandwiched between skatewear outlets and nail bars.

But these weren't just galleries. They were the Thomas Kinkade experience – minus the alcohol and Valium, of course. Clients would be ushered into a climate-controlled viewing room to maximise the Kinkadeness of the whole place, and their experience. Some galleries offered "master highlighters", trained by someone not far from the master himself, to add a hand-crafted splash of paint to the desired print and so make a truly unique piece of art, as opposed to the framed photographic print that was the standard fare.

The artistic credo was expressed best in the 2008 movie Thomas Kinkade's Christmas Cottage. Peter O'Toole, earning a crust playing Kinkade's artistic mentor, urges the young painter to "Paint the light, Thomas! Paint the light!".

Kinkade's art also went beyond galleries through the "Thomas Kinkade lifestyle brand". This wasn't just the usual art gallery giftshop schlock: Kinkade sealed a tie-in with La-Z-Boy furniture (home of the big butt recliner) for a Kinkade-inspired range of furniture. But arguably his only great artwork was "The Village, a Thomas Kinkade Community", unveiled in 2001. A 101-home development in Vallejo, outside San Francisco, operating under the slogan: "Calm, not chaos. Peace, not pressure," the village offers four house designs, each named after one of Kinkade's daughters. Plans for further housing developments, alas, fell foul of the housing crisis.

In the years before his death, Kinkade's business and his life took a battering. There were allegations of malpractice, and his company declared bankruptcy, unable to pay its creditors following a series of court judgments ordering him to pay $860,000 for defrauding the owners of two failed franchises.

Following his separation from his wife and spiralling alcoholism, Kinkade's behaviour became erratic: he allegedly caused a scene at a Siegfried & Roy show in Las Vegas by repeatedly shouting "Codpiece!" at the ageing illusionists. He also engaged in what he termed "ritual territory marking" at a California Disneyland hotel, urinating on a Winnie the Pooh figure.

Kinkade's death went largely unnoted in the art world. There were no lengthy obituaries in the quality press, critics did not line up to extol the beauty or the influence of his art. Maybe they missed a trick. For while Kinkade's work is at best humdrum and technically adequate, its popularity tells us something about his public, about a desperate yearning for nostalgia that pervades parts of American life, a return to the safe glow of some imagined past.

"It's not the world we live in," Kinkade said of his painting, "it's the world we wished we live in. People wish they could find that stream, that cabin in the woods."

And it could be that with his mastery of the market, and his understanding of how to sell his work – "When I got saved, God became my art agent," he once said – Kinkade was the natural heir to the apostle of mass production, Andy Warhol.

"There's been million-seller books and million-seller CDs," Kinkade explained. "But there hasn't been, until now, million-seller art. We have found a way to bring to millions of people, an art that they can understand."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion