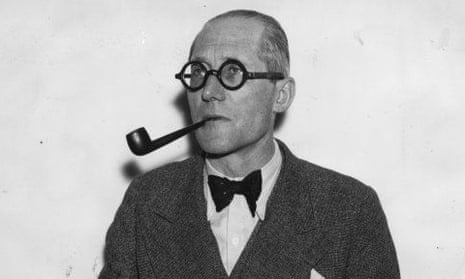

The first time I met Corbusier was in Bombay in 1952 at a diplomatic party when my host begged me to go and talk to “that great lanky fellow over there, standing by himself with a glass of brandy. He speaks no English and I have no time to entertain him; he is French, do help out.” My host had not told me who the tall, handsome, elderly man was.

I suggested we sit down and asked the tall man what he was doing in Bombay. He was furious and began to unburden himself at once. His trouble was money. “Indians are cheating me. I am going to Delhi to tell Nehru. Non, ça ne se passera pas comme ça!” The Reserve Bank of India had raised objections to his remitting to France the money which had been paid to him by Mrs Sarabhai – the widow of a well-to-do Ahmedabad mill owner.

The next time I met Corb was in the plane going to Delhi the very next day. We naturally sat together and I mentioned that I was a journalist. This opened a new floodgate of recriminations. Corb was obviously suffering from some sort of persecution complex where the press was concerned. The press was after him: they made money out of him, they never gave him money when they interviewed him; indeed it was the reporter who made the money, this was unfair. And to cap it all they misquoted him; this had happened more than once over his conception of the Maison Soleil. The words “Maison Soleil” gave me the clue to his identity.

As we were getting off the plane he asked me what I was doing that evening: “Catching a train, I am afraid,” I said. “ Pity. You are fat and I like my women fat. We could have spent a pleasant night together.” He said this quite casually. He was not being offensive, he was being factual, so involved in his own ego that it did not occur to him that it might have been better put and more gallant to spend some time on preliminaries. So gigantic was Corb’s egotism that he probably considered it enough of an honour for a humble mortal to provide a genius like him with a night’s relaxation.

That evening I was catching the train to Chandigarh where the Manchester Guardian was sending me to write about the new capital for the Punjab which Le Corbusier was building, together with Jane Drew, Maxwell Fry, and Pierre Jeanneret, according to a master plan prepared by the American town planner Albert Mayer. I spent a few exciting days as the guest of Jane Drew – in those days there was no hotel and no really comfortable place to stay in Chandigarh, which was still much in its embryo. On the third day Jane said, with that deep, warm, throaty, voice of hers: “Taya, you are in luck. Corb is coming tonight, and you will meet him at Jeanneret’s for drinks. Put on a nice dress and if I can give you a tip do not talk shop to him at the party. He hates that. Just be nice and try to get an appointment with him in his office.”

Corb was almost gay. He had seen Nehru, who had given orders to the Reserve Bank, and he liked my dress. In fact, he was almost gallant. He spent the evening discussing women, prostitution, the impotence of Indian males, and his own wife. “I absolutely fail to understand her. Of course she is pretty stupid, mais quand même.

I give her all the money she wants but that is not enough for her. No. Madame wants children! She keeps pestering me for children. I hate children. She already has a little dog, that should be good enough. Take another dog, have two dogs by all means, but leave me alone is what I say to her.”

And he told me with chuckles of glee how Mrs Sarabhai had pleaded with him for railings or some sort of garde-fou on the terrace and balconies of her house in Ahmedabad. “The good woman was afraid that when her sons get married their children would fall off and kill themselves, as if I cared. As if I, Le Corbusier would compromise with design for the sake of her unborn brats!”

When I told him how much I had liked the drawings and compositions of bulls he had given Jane Drew, he beamed. “People do not know it because they are hypnotised by categories, but I am a much greater artist than Picasso; a much better draftsman.” By the time he had had a few drinks he was paying me the sort of compliments Rubens must have paid Hélène Fourment when she was far gone with child. Had I not studied medicine I would have found his anatomical precision embarrassing. I had always known that I was fat, but I had not realised before that I looked as fat as all that. Taking advantage of his enthusiasm for my curves I asked if I could come and see him in his office the next day to ask questions about Chandigarh. He squeezed my hand, gave me a time, and warned: “Don’t be late. I hate waiting.”

At the appointed hour I was there, my list of questions written out not to waste the great man’s time. “There you are. We are not going to discuss architecture. I hate talking shop to a woman. That blasted blind will not come down and the air-conditioning does not work. Besides, there is no convenient place. You had better come to my room in Maiden’s Hotel in Delhi tomorrow evening and if you are a sensible girl before you go you can choose one of those bull drawings you said you liked. Now run along, don’t stand there wasting my time.” It had all been said so fast and with such complete matter-of-factness that it was impossible to take offence. To strike a Victorian pose would have been ridiculously melodramatic. I simply walked out.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion