Matt Hall vividly remembers his job interview with Robert Rauschenberg. A mutual acquaintance had approached Hall, then sous chef at a restaurant on the island of Captiva, off Florida, to see whether he would be interested in managing the artist’s property nearby. As Hall approached his beach house, the artist emerged on to the balcony. “Mr Rauschenberg, so good to see you again,” Hall called up (Rauschenberg was a regular customer). “Oh, Matt, don’t call me Mr Rauschenberg. Call me Bob,” came the reply.

“I don’t know why,” remembers Hall, sitting in the lounge of a glorious beach house with a yellow and blue Rauschenberg collage hanging on the wall, “but I said, ‘Bob: backwards or forwards, it’s spelt the same. It reminds me of the joke about the dyslexic who tried to commit suicide: he jumped behind the train.’” Rauschenberg cackled for an inordinate length of time, Hall adds, given the poor quality of the joke. Finally, the artist explained himself: “I’m dyslexic. See you Monday, sweets.”

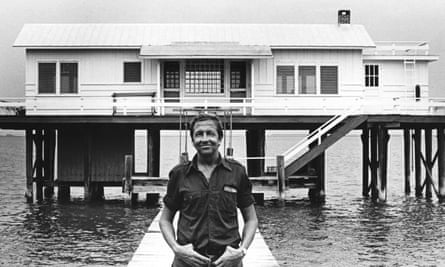

Rauschenberg has been a constant presence on Captiva ever since. Although he died in 2008, the 20-acre estate he created is now a retreat, where artists work together in a spirit inspired by his philosophy: open, collaborative, risk-taking. They stay in any of nine cottages and beach houses lapped by the Gulf of Mexico – one is built on stilts, with a balcony from which you can fish – surrounded by Rauschenberg’s art and piles of books. There’s even a resident chef: Rauschenberg was a foodie before the term was even invented. The artist and musician Laurie Anderson came here just after her husband Lou Reed died in 2013, to recharge and start working again.

Arriving on Captiva earlier this month, it is clear what drew Rauschenberg here: the six-mile island is relaxed, sun-baked, and teeming with flora and fauna, from the tiny lizards darting everywhere to the manatees swimming in the bay. By night, rabbits, bobcats and great horned owls emerge in “the jungle”, a wooded area masterminded by the artist, where a bronze seat faces the sunset.

Rauschenberg started visiting in 1962, before moving to Captiva nine years later, describing it as “the foundation of my life and my work… the source and reserve of my energies”. His work by then had become ambitious and complicated; Captiva forced a return to simplicity, and the first things he produced were a selection of wall sculptures made from battered cardboard boxes.

For the world beyond Captiva’s white sands, however, a reacquaintance with Robert Rauschenberg is long overdue. In Britain, there has been no major retrospective of his work since 1981, while the last big US survey, at the Guggenheim in New York, took place in 1997. That will change next month, when Tate Modern opens a London retrospective; it will then move to Moma in New York next May, and after that to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Rauschenberg left a bold and indelible mark on the 20th century. His combines, which integrated the flotsam and trash of everyday life, including the artist’s own duvet in Bed (1955), were neither painting nor sculpture, and proved that anything could be the material of art. At Tate Modern, pride of place will be given to Monogram 1955–59, a horizontal canvas on which perches a stuffed goat with a tyre around its midriff; the work thrilled and scandalised when it was first shown at Castelli’s gallery in New York, and rapidly became synonymous with the artist’s iconoclasm. Since then, his relevance has only increased, says Leah Dickerman, co-curator of the new retrospective: “When you open a gallery and see the art that’s made out of the stuff of the real world, that’s coming off the walls, that’s interdisciplinary in its approach, all that is the legacy of Rauschenberg.”

Little in Rauschenberg’s background suggested he was destined to be a great artist. Born in 1925, the son of an oil worker in Port Arthur, Texas, he struggled at school and was suspended after refusing to dissect a live frog (an early sign of his fondness for animals); a month later, he was called up for the draft. Rauschenberg realised his gift for drawing only when his pen portraits of comrades in the navy made him popular for the first time in his life; it didn’t strike him that being an artist was a real job until he saw three oil paintings at the Huntington art gallery in San Marino, California, including Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy. “Behind each of them was a man whose profession it was to make them,” he told the art critic Robert Hughes. “That just never occurred to me before.”

After Rauschenberg was discharged from the navy, he made his way to Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he laboured under the punishing tutelage of Josef Albers, who had taught at the Bauhaus in Germany. “He’d pick up something of mine and say, ‘This is the most stupid thing I have ever seen, I don’t even vant to know who did it,’” remembered Rauschenberg, quoted in Calvin Tomkins’ biography. (Architectural Digest magazine revealed that teacher and pupil were reunited by the Obamas, in one of the dining rooms at the White House, where a 1998 Rauschenberg painting hangs adjacent to two works by Albers.)

When he moved to New York two years later, Rauschenberg received an equally chilly reception from the hard-drinking abstract expressionists who hung out at the Cedar Tavern in the East Village. “Every time he went, [Jackson] Pollock would ask him who he was and what he was doing there,” says Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate Modern and co-curator of the new retrospective. “Always friendly but always forgetting.” They never acknowledged him as a peer, still less a successor.

There was something else that set Rauschenberg apart: he was gay. He had married the artist Susan Weil in 1950, with whom he had a son, Christopher, a year later; but the pair divorced in 1953, both realising that Rauschenberg was attracted to men. He travelled, worked and had an affair with the painter Cy Twombly. Then, in 1956, he embarked on a six-year relationship with his New York neighbour, abstract expressionist Jasper Johns. (To fund their work, the two artists collaborated on a number of commercial projects, including window displays for Tiffany & Co.)

In recent years, critics have either glossed over the sexuality of both men, or interpreted Rauschenberg’s work as a coded expression of gay desire: “Stuffed cocks and bound pillows and fabric sacks that do double duty as stand-ins for butt cheeks and scrotums,” the artist David Spiher wrote in an article excoriating New York’s Met for refusing to acknowledge Rauschenberg’s homosexuality in a 2006 show.

Dickerman and Borchardt-Hume say their exhibition will be more direct. “I think in 2016 we can be very straightforward about it,” Dickerman says. “That he is a gay man in New York, pre-Stonewall, that this structures his social circle and ways of thinking, that it’s shaping part of his identity. But it’s not the totality, either.”

“I think when Rauschenberg came of age it was a different time,” says the film-maker Charles Atlas, one of the first to take up an artist’s residence on Captiva. “Even when he was more or less out as a gay artist, he wasn’t that public about it. Both he and Jasper were famous very young, and when Andy Warhol came on the scene, they thought he was too swish.” Atlas laughs: “They were more or less the straight-acting gays. The social world really was not that tolerant of openly gay people. The gay world was a separate world.”

While Warhol was an enigmatic figure, Rauschenberg was outgoing, a man who loved to host big Thanksgiving dinners. As Hall points out, there are photographs all over the walls of the cottages on Captiva, and Rauschenberg is smiling widely in each one. He was also a heavy drinker. “He was very gregarious, but he wasn’t a mean drunk,” says Atlas, who met him around a dozen times. “He just got more friendly.” Hall remembers wild parties in the 1990s that spawned “stories I will take to the grave. He was just something to be around.”

The Cedar Tavern crew may have spurned him, but Rauschenberg found supportive mentors in the composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham – and, since the two men were a couple as well as collaborators, perhaps role models for living, too. “I think, in Cage, he recognised that all these possibilities were open in every way – in terms of art making, in terms of how you live your life, how you conduct your relationships,” Borchardt-Hume says. Rauschenberg started to work with them in 1952, ensuring that the performances of the Merce Cunningham Company were as avant garde in their approach to set, costume and lighting as they were when it came to Cage’s music and Cunningham’s choreography. First staged in 1964, towards the end of the trio’s working relationship, Winterbranch had the audience shielding their eyes against a sudden dazzling light, while the dancers were swathed in gloom. “It was very, very dark on stage,” Atlas remembers. “There were battery-operated lights held by various people in the wings, and the lighting design was very erratic. It had nothing to do with the dance.”

Rauschenberg took to performing himself: in the 1965 piece, Spring Training, he followed 30 turtles with torches attached to their shells, walking on to the stage on stilts. (“The turtles turned out to be real troupers,” he noted at the time.) Both the Tate and Moma have recently extended their galleries to create new performance spaces, but they won’t be hosting these works; footage from Rauschenberg’s own performances will be shown instead. The eight works that Rauschenberg choreographed, with instructions such as “‘jerk leg up, roll forward in a convulsive manner”, were intended to be performed by the artist only.

The 60s brought a political dimension to Rauschenberg’s work. Retroactive I (1963) used the silk-screen technique he and Warhol borrowed from the commercial art world at around the same time, but to very different ends. Warhol’s silk screens of John F Kennedy were ironic and detached; Rauschenberg’s use of Kennedy’s image, along with a picture of an astronaut and the Sunkist orange logo, have a more anxious sincerity. The silk screens, according to Borchardt-Hume, “have a very clear sense of, ‘This is the world I live in, and this is what I care about.’”

By the end of the decade, the tone of his work had darkened. Originally commissioned for the cover of a magazine, Signs is a collage of photographic images including Martin Luther King Jr in his coffin, the moon landings, a race riot, the Vietnam war, and both Bobby and John Kennedy. “You have a sense that the buoyant optimism of the postwar period, the early 1960s, had given way to a very different mood,” Borchardt-Hume says. “And I think Captiva seemed a reprieve from that.”

Compared with his combines, the more simple work Rauschenberg produced on Captiva was not well received. Borchardt-Hume argues that subsequent developments in art make mid-70s projects such as the Jammers, inspired by Indian textiles, and Rauschenberg’s later works on metal, easier to appreciate in retrospect. An artist such as Philippe Parreno, whose work currently fills Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, “would immediately cite Rauschenberg’s model of collaboration between artists and scientists, how people with different technological expertise can come together”.

Founded in 1966, Rauschenberg’s organisation Experiments in Art and Technology (Eat) was a kind of matchmaking service between artists, engineers and scientists, which at its peak had 6,000 members. His desire to use art as a means of breaking down barriers saw its grandest flowering in the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (Roci), which began in 1984. This seven-year project saw the artist travel to countries with repressive regimes such as Cuba, Tibet and China, to work with local artists; he used his home on Captiva as collateral to fund it.

“Roci had a huge impact in China,” Dickerman says. “There is a generation of artists who saw him as a role model. Whether or not their work looks like his, the way he dabbled in an economy of ideas was very powerful to them.”

Back on Captiva, Hall agrees that “Bob was never an elitist.” Before a big gallery opening anywhere in the world, he would usually be found “on the end stool at the farthest satellite bar, engaged with the bartender. I would come and say, ‘Boss, they’re ready for you,’ and you could see the bartender’s eyes just get huge, going, ‘Oh my God, you’re Rauschenberg?’ And he’d go, ‘Yeah, very nice to meet you,’ throw a $100 bill down and go. That was Bob – he was down to earth, would talk to anybody. He was notorious in the streets of New York for just handing out $100 bills to people.”

Rauschenberg was not motivated by money, Hall says; he would open drawers in his beach house and find cheques for several thousand dollars. His Christmas gifts were mangoes or homemade hot sauce. “He had all these wonderful recipes that were never written down. It was just like him creating a piece of art: ‘Let me put a little of this in it and taste it. Uh, let’s try and correct it.’”

Though Hall first worked for the artist as his gardener, Rauschenberg was keen to get his opinion, gradually involving him in the creation of his work. “He’d say, ‘Get yourself a drink.’ He always had the TV on, and you’d be sat there talking about anything, drugs, sex, rock’n’roll, politics, art – it didn’t matter. All of a sudden, he’d be looking at the blank canvas that was on the table and he’d kind of get quiet, and you knew that was time for him to go to work.”

Rauschenberg died on the island, in his light-filled studio, as he had wished, with his closest friends – including Hall and Darryl Pottorf, his partner of 25 years – by his side. The studio is at the top of steep stairs; his friends took his body down in an elevator. “He would always travel and I’d give him a kiss and say ‘Hey, babe, have a safe trip.’ He’d say, ‘OK, sweets, see you when I get back,’” says Hall. “But the finality of him leaving that last time, I can’t even describe it. It was brutal.”

Yet Rauschenberg’s legacy thrives, not just through his experiments or his openness of spirit, but because underneath it all there is a sense of sheer aesthetic delight. “Even if he hadn’t been that adventurous a person, he was so talented at making visual beauty – and that’s the key, really,” Atlas says. “The imitators: they’re just not the same thing. You can take all his ideas and combine them, but he made truly beautiful works of art.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion