A group of wonky air-conditioning ducts wiggle into the room, like snakes in search of prey. A ceiling appears to have been hastily shored up with a jumble of wooden planks. And a smoke detector dangles from the end of its cable. There’s a reason for all the artful bodging: they’re part of a shrine to the king of cobbled-together contraptions, the patron saint of make do and mend, William Heath Robinson.

“We wanted it to look builderly,” says Adam Zombory-Moldovan, the architect of the new Heath Robinson Museum, which stands on the edge of Pinner Memorial Park in London. The little pavilion has been built with £1.3m of lottery funding to house an almost 1,000-strong collection of the artist’s drawings. “It might appear illogical in places,” adds Zombory-Moldovan, “but it all has structural integrity.”

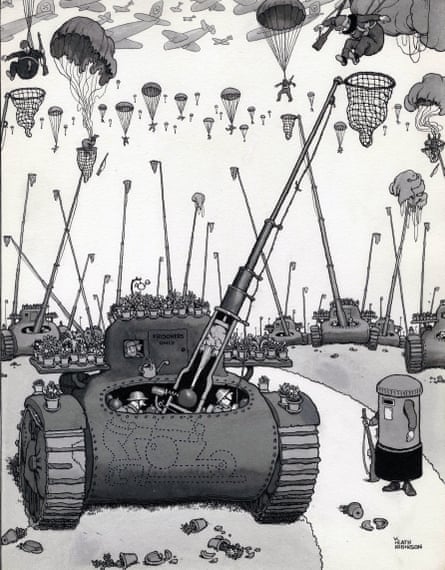

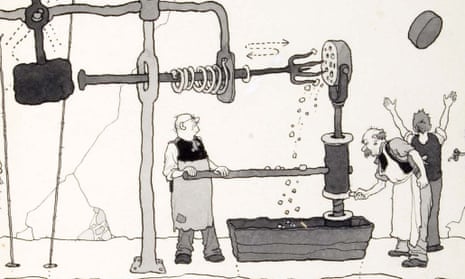

The same can’t be said for some of Heath Robinson’s weird and wonderful inventions. In one of the two lofty gallery rooms hangs an illustration of one of his magnificently complicated contraptions, entitled Doubling Gloucester Cheeses by the Gruyère Method. A series of pulleys and cogs – held together with knotted string and operated by his ubiquitous cast of portly, balding, bespectacled men – leads to a rotating fork that gouges out holes from rounds of Gloucester, thus making the rationed cheese go further. It was one of his many drawings that made light of the strenuous conditions of wartime, featured in the museum’s opening exhibition of the artist’s work during the first and second world wars.

“His humour was a great weapon and a tonic,” says curator Geoffrey Beare, a lifelong Heath Robinson fan and chair of the Imaginative Book Illustration Society, who had a long career in the Ministry of Defence before retiring to focus on the creation of the museum. “He had a knack for making the Germans absurd rather than threatening, which raised morale both at home and among the troops.”

His series German Breaches of the Hague Convention depicts the hapless enemy variously using laughing gas rather than mustard gas, or suspending gramophones from fishing rods to bore a British sentry to death with patriotic songs.

The frugal, makeshift experience of wartime rationing is brilliantly captured in his tired, worn worlds, where cracked walls and roofs are hastily papered over and nailed together – but some of the jokes now seem a little strained and dated. You occasionally find yourself sympathising with an editor who, having looked through the artist’s portfolio early in his career, said: “If this work is humorous, your serious work must be very serious indeed.”

In fact, as a visit to the museum shows, Heath Robinson was a rather reluctant humorist. Although he is now synonymous with drawings of harebrained inventions manned by bungling technicians (his name entered the dictionary in 1912 as a synonym for absurd and overcomplicated devices), they make up only a quarter of his work. The museum tells the story of a man with higher artistic ambitions, who only turned to these comic illustrations for magazines to pay the bills.

“He saw himself as a serious artist, not a jokey cartoonist,” says Beare, pointing to a photograph of Heath Robinson in his studio in 1929, surrounded by his paintings and book illustrations, not a humorous drawing in sight. Trained at the Islington School of Art and the Royal Academy, he began his career illustrating books, from Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytales to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Beare considers this to be his most accomplished work. It’s an area that shows his versatility: these romantic illustrations have an almost Pre-Raphaelite sensibility, while his later watercolours verge on stripped art deco. But it was the surreal scenes of elaborate, dysfunctional contraptions, published in the Tatler, the Bystander and the Sketch, that made his name, attracting such admirers as HG Wells, who wrote to him in 1914: “Your absurd, beautiful drawings … give me a peculiar pleasure of the mind like nothing else in the world.”

By the 1920s, he was known as the Gadget King. The codebreakers of Bletchley Park even named one of their whirring contraptions after him. He worked on advertisements, too, producing drawings for over 100 companies, selling everything from steel girders and Swiss rolls to toffee, beef essence and asbestos cement, depicting each product being manufactured in a fantastical imaginary process.

Still, as Beare explains, it wasn’t the mechanisms that interested him. He wasn’t an amateur inventor and never actually made any of his machines (it might come as a disappointment to learn that there aren’t any models in the museum). “They were metaphors for the inflated structures people build to justify their own existence,” Beare says. “They are about the human condition, the workings of fate and the weakness and self-importance of man. If he were alive now, I imagine his subject might be the world of HR departments.”

Or perhaps he’d be tackling the housing crisis. The drawings from his 1936 book How to Live in a Flat are eerily prescient, with ingenious ideas for living in cramped apartments, from folding spare beds to dining tables hanging above baths, to how residents could practise “communal eurythmics” on their tiny balconies. Anyone for rooftop hiking?

- Heath Robinson at War ends 8 January.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion